Intellectuals and the Maoists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

GW 131 Spring 2017

The Gandhi Way Tavistock Square, London 30 January 2017 (Photo by John Rowley) Newsletter of the Gandhi Foundation No.131 Spring 2017 ISSN 1462-9674 £2 1 Gandhi Foundation Summer Gathering 2017 Theme: Inspired by Gandhi 22 July - 29 July 2017 St Christopher School, Barrington Road, Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire SG6 3JZ Further details: Summer Gathering, 2 Vale Court, Weybridge KT13 9NN or Telephone: 01932 841135; [email protected] Gandhi Foundation Annual Lecture 2017 to be given by Satish Kumar Saturday 30 September Venue in London to be announced later An International Conference on Mahatma Gandhi in the 21st century: Gandhian Themes and Values Friday 28 April 2017 at the Wellcome Trust Conference Centre, 183 Euston Road, London NW1 2BE Organised by Narinder Kapur & Caroline Selai, University College London Further details on page 23 Contents Climate Change – A Burning Issue Jane Sill An Experiment in Love: Maria Popova Martin Luther KIng on the Six Pillars of Nonviolent Resistance Mahatma Gandhi and Shrimad Rajchandraji Reviews: Pax Gandhiana (Anthony Parel) William Rhind Selected Works of C Rajagopalachari II Antony Copley Obituaries: Arya Bhardwaj Gerd Ledermann 2 Climate Change – A Burning Issue Jane Sill This was the title of this year's annual multifaith gathering which took place on 28th January at Kingsley Hall where Gandhi Ji had stayed in 1931 while attending the Round Table Conference. The title had been chosen some time ago but, in view of the drastic change in US policy, it could not have been a more fitting subject. Often pushed aside in the light of apparently more pressing issues, this is a subject which unfortunately is bound to come into higher profile as the results of global warming become more evident – unless of course there are serious policy changes worldwide. -

Growing Tentacles and a Dormant State

Maoists in Orissa Growing Tentacles and a Dormant State Nihar Nayak* “Rifle is the only way to bring revolution or changes.”1 The growing influence of Left Wing extremists (also known as Naxalites)2 belonging to the erstwhile People’s War Group (PWG) and Maoist Communist Center (MCC) 3 along the borders of the eastern State of Orissa has, today, after decades of being ignored by the administration, become a cause for considerable alarm. Under pressure in some of its neighbouring States, the * Nihar Nayak is a Research Associate at the Institute for Conflict Management, New Delhi. 1 The statement made by Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) PWG Orissa Secretary, Sabyasachi Panda, in 1996. 2 The Naxalite movement takes its name from a peasant uprising, which occurred in May 1967 at Naxalbari in the State of West Bengal. It was led by armed Communist revolutionaries, who two years later were to form a party – the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (CPI-ML), under the leadership of Charu Mazumdar and Kanu Sanyal, who declared that they were implementing Mao Tse Tung’s ideas, and defined the objective of the new movement as 'seizure of power through an agrarian revolution'. The tactics to achieve this were through guerilla warfare by the peasants to eliminate the landlords and build up resistance against the state's police force which came to help the landlords; and thus gradually set up ‘liberated zones’ in different parts of the country that would eventually coalesce into a territorial unit under Naxalite hegemony. In this paper, the term ‘Naxalite’ has been used synonymously with ‘Maoist’ and ‘rebel’ to denote Left-Wing extremists. -

NON-VIOLENCE NEWS February 2016 Issue 2.5 ISSN: 2202-9648

NON-VIOLENCE NEWS February 2016 Issue 2.5 ISSN: 2202-9648 Nonviolence Centre Australia dedicates 30th January, Martyrs’ Day to all those Martyrs who were sacrificed for their just causes. I have nothing new to teach the world. Truth and Non-violence are as old as the hills. All I have done is to try experiments in both on as vast a scale as I could. -Mahatma Gandhi February 2016 | Non-Violence News | 1 Mahatma Gandhi’s 5 Teachings to bring about World Peace “If humanity is to progress, Gandhi is inescapable. He lived, with lies within our hearts — a force of love and thought, acted and inspired by the vision of humanity evolving tolerance for all. Throughout his life, Mahatma toward a world of peace and harmony.” - Dr. Martin Luther Gandhi fought against the power of force during King, Jr. the heyday of British rein over the world. He transformed the minds of millions, including my Have you ever dreamed about a joyful world with father, to fight against injustice with peaceful means peace and prosperity for all Mankind – a world in and non-violence. His message was as transparent which we respect and love each other despite the to his enemy as it was to his followers. He believed differences in our culture, religion and way of life? that, if we fight for the cause of humanity and greater justice, it should include even those who I often feel helpless when I see the world in turmoil, do not conform to our cause. History attests to a result of the differences between our ideals. -

"NAXALITE" MOVEMENT in INDIA by Sharad Jhaveri

-518- We are not yet prepared to call ism, feudalism and comprador-bureaucrat the leaders of the CPI(M) "counter-revo- capital"! -- whatever that might mean. lutionaries" although objectively they play the role of defenders of bourgeois Indeed the "Naxalite" revolt against property. That is a logical consequence the leadership of the CPI(M) reflects to an of their opportunist class-collaboration- extent the growing revolt of the rank and ist policies emanating out of their er- file against the opportunist sins of the roneous and unhistorical strategy of a leadership. The ranks react in a blind and "people's democratic revolution'' in India. often adventurist manner to the betrayals of the masses by the traditional Stalinist But then the Naxalites, despite parties. all their fiery pronouncements regarding armed action and "guerrilla warfare," are For the present, Maoism, with its also committed to the strategy of a four- slogan "power flows from the barrel of a class "people's democratic front" -- a gun," has a romantic appeal to these rev- front of the proletariat with the peasant- olutionary romanticists. But the honest ry, middle class, and the national bour- revolutionaries among them will be con- geoisie to achieve a "people's democratic vinced in the course of emerging mass revolution. struggles that the alternative to the op- portunism of the CPI(M) is not Maoist ad- What is worse, the Naxalites under- venturism but a consciously planned rev- rate the role of the urban proletariat as olutionary struggle of workers and peas- the leaders of the coming socialist revo- ants, aimed at overthrowing the capital- lution in India. -

Bomb Target Norway

Bomb target Norway About Norwegian political history in a tragic background, the background to the Norwegian fascism. Militarism and na- tionalism are the prerequisites for fas- cism. By Holger Terpi Norway is a rich complex country with a small wealthy militarist and nationalist upper class, a relatively large middle class and a working class. The little known Norwegian militarism has always been problematic. It would censorship, war with Sweden, occupy half of Greenland1, was opponent of a Nordic defense cooperation, garden Norway into NATO2 and EEC, would have plutonium and nuclear weapons3, as well as, monitor and controlling political opponents, in- cluding the radical wing of the labor movement, pacifists and conscientious objectors. And they got it pretty much as they wanted it. One example is the emergency law or emergency laws, a common term for five laws adopted by the Storting in 1950, which introduced stricter measures for acts that are defined as treacherous in war, and also different measures in peacetime, such as censorship of letters, phone monitoring etc.4 1 Legal Status of Eastern Greenland (Den. v. Nor.), 1933 P.C.I.J. (ser. A/B) No. 53 (Apr. 5) Publications of the Per- manent Court of International Justice Series A./B. No. 53; Collection of Judgments, Orders and Advisory Opinions A.W. Sijthoff’s Publishing Company, Leyden, 1933. 2 Lundestad , Geir: America, Scandinavia, and the Cold War 1945-1949. Oslo, University Press, 1980. - 434 pp. Paradoxically, according to Lundestad, the U.S. preferred socialist governments in Scandinavia rather than conservative, the reason was that they were perceived as "the strongest bulwark" against communism 3 Forland, Astrid: Norway’s nuclear odyssey: from optimistic proponent to nonproliferator. -

Searchable PDF Format

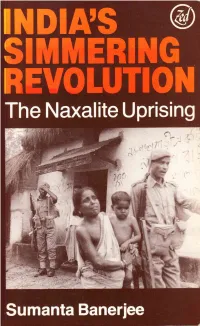

lndia's Simmering Revolution Sumanta Banerjee lndia's Simmeri ng Revolution The Naxalite Uprising Sumanta Banerjee Contents India's Simmering Revolution was first published in India under the title In the llake of Naxalbari: A History of the Naxalite Movement lVlirps in India by Subarnarekha, 73 Mahatma Gandhi Road, Calcutta 700 1 009 in 1980; republished in a revised and updated edition by Zed lrr lr<lduction Books Ltd., 57 Caledonian Road, London Nl 9BU in 1984. I l'lrc Rural Scene I Copyright @ Sumanta Banerjee, 1980, 1984 I lrc Agrarian Situationt 1966-67 I 6 Typesetting by Folio Photosetting ( l'l(M-L) View of Indian Rural Society 7 Cover photo courtesy of Bejoy Sen Gupta I lrc Government's Measures Cover design by Jacque Solomons l lrc Rural Tradition: Myth or Reality? t2 Printed by The Pitman Press, Bath l't'lrstnt Revolts t4 All rights reserved llre Telengana Liberation Struggle 19 ( l'l(M-L) Programme for the Countryside 26 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Banerjee, Sumanta ' I'hc Urban Scene 3l India's simmering revolution. I lrc Few at the ToP JJ l. Naxalite Movement 34 I. Title I lro [ndustrial Recession: 1966-67 JIa- 322.4'z',0954 D5480.84 I lre Foreign Grip on the Indian Economy 42 rsBN 0-86232-038-0 Pb ( l'l(M-L) Views on the Indian Bourgeoisie ISBN 0-86232-037-2 Hb I lrc Petty Bourgeoisie 48 I lro Students 50 US Distributor 53 Biblio Distribution Center, 81 Adams Drive, Totowa, New Jersey l lrc Lumpenproletariat 0'1512 t lhe Communist Party 58 I lrc Communist Party of India: Before 1947 58 I lrc CPI: After 1947 6l I lre Inner-Party Struggle Over Telengana 64 I he CPI(M) 72 ( 'lraru Mazumdar's Theories 74 .l Nlxalbari 82 l'lre West Bengal United Front Government 82 Itcginnings at Naxalbari 84 Assessments Iconoclasm 178 The Consequences Attacks on the Police 182 Dissensions in the CPI(M) Building up the Arsenal 185 The Co-ordination Committee The Counter-Offensive 186 Jail Breaks 189 5. -

Conflict, Violence, Causes and Effects of Naxalism: in Vidarbha

Volume: 5 | Issue: 11 | November 2019 || SJIF Impact Factor: 5.614||ISI I.F Value: 1.188 ISSN (Online): 2455-3662 EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (IJMR) Peer Reviewed Journal CONFLICT, VIOLENCE, CAUSES AND EFFECTS OF NAXALISM: IN VIDARBHA Dr. Deoman S. Umbarkar Assistant Professor, Dept. of Sociology, Late V.K. College, Rohana, Tah. Arvi, Distt. Wardha, Maharashtra, India. ABSTRACT This paper poses two questions : is it a fact that there is more violence in Naxalite (i.e. Maoist) affected districts compared to districts which are free of Naxalite activity? can the fact that Naxalite activity exists in some districts of India but not in others, be explained by differences between districts in their economic and social conditions? Using a number of sources, this study identifies districts in India in which there was significant Naxalite activity. Correlating these findings with district level economic, social and crime indicators, the econometric results show that, after controlling for other variables, Naxalite activity in a district had, if anything, dampening effect on its level of violent crime and crimes against women. Furthermore, even after controlling for other variables, the probability of a district being Naxalite affected rose with an increase in its poverty rate and fell with a rise in its literacy rate. So, one prong in an anti-Naxalite strategy would be to address the twin issues of poverty ad illiteracy in India. As the simulations reported in the paper show, this might go a considerable way in ridding districts of Naxalite presence. INTRODUCTION Naxalisem is a crucial problem now a day's A Naxal or Naxalite is a member of the facing by tribal's as well as common person. -

The Changing Role of Women in Hindi Cinema

RESEARCH PAPER Social Science Volume : 4 | Issue : 7 | July 2014 | ISSN - 2249-555X The Changing Role of Women in Hindi Cinema KEYWORDS Pratima Mistry Indian society is very much obsessed with cinema. It is the and Mrs. Iyer) are no less than the revered classics of Ray or most appealing and far reaching medium. It can cut across Benegal. the class and caste boundaries and is accessible to all sec- tions of society. As an art form it embraces both elite and Women have played a number of roles in Hindi movies: the mass. It has a much wider catchment area than literature. mythical, the Sati-Savitri, the rebel, the victim and victimizer, There is no exaggeration in saying that the Indian Cinema the avant-garde and the contemporary. The new woman was has a deep impact on the changing scenario of our society in always portrayed as a rebel. There are some positive portray- such a way as no other medium could ever achieve. als of rebels in the Hindi movies like Mirch Masala, Damini, Pratighat, Zakhm, Zubeida, Mritudand and several others. Literature and cinema, the two art forms, one verbal in form The definition of an ideal Indian woman is changing in Hindi and the other visual, are not merely parallel but interactive, Cinema, and it has to change in order to suit into a changing resiprocative and interdependent. A number of literary clas- society. It has been a long hundred years since Dadasaheb sics have been made popular by the medium of cinema. Phalke had to settle for a man to play the heroine in India’s first feature film Raja Harishchandra (1913) and women in During its awesome journey of 100 years, the Indian Cinema Hindi cinema have come a long way since then. -

Alternative Cinema(S) of South Asia/ Submission of Abstracts: 20Th August 2020

H-Film Alternative Cinema(s) of South Asia/ Submission of Abstracts: 20th August 2020 Discussion published by Elif Sendur on Wednesday, July 22, 2020 GGSIP University, New Delhi, Shivaji University, Kolhapur contact email: [email protected] South Asia in Alternative Cinema(s) Concept Note South-Asian Cinema comprises the body of cinematic works produced in South–Asian Countries - India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh, Maldives, Bhutan, Pakistan and Afghanistan. It offers an indispensable source for understanding the vicissitudes of the region addressing its social, political and cultural issues. It is significant to note that for South–Asian Cinema has been a site of national, religious, ethnic and cultural debates. These films are a valuable source to understand social, cultural and political dynamics of the region. Despite its seemingly common problems such as the issues of minorities, women, violence, fluid contact zones, disputed borders and challenges of modernity, the region is also known for its cultural, religious, ethnic and linguistic diversity. Though there are superficial similarities yet each country/region has its unique dynamics, social system, cultural practices and circumstances. The complex nature of the region demands critical engagement and nuanced understanding of its society, culture, politics and art. The present project shifts the focus from mainstream cinema to all kinds of alternative cinema(s). Since there are many forms of alternate cinematic expressions, it is proposed to call in alternate cinema(s). The present project invites original research papers/chapters from film scholars, film writers and filmmakers reflecting on Parallel Cinema or New Wave or New Cinema or Avant Garde in the past and Indies, new cinema or New (Middle) Cinemas, short films or experimental films in the post-liberalization era across South Asia to understand region specific issues. -

Kanu Sanyal–The Voice of Indian Revolution Subrata Basu

LOOKING BACK Kanu Sanyal–the Voice of Indian Revolution Subrata Basu Kanu Sanyal–the helmsman of historic Naxalbari uprising in May, 1967 breathed his last on 23 March, 2010. He was 81. Kanu Sanyal was the general Secretary of CPI(ML) which he along with some other leading organizers formed in January 2005 in AP. With his passing away there comes to an end of a six-decade-long turbulent revolutionary political life that had its beginning in the small town of Siliguri when he was a vibrant youth of just 21. Kanu Sanyal's end came in Hatighisa village—it is the very village and its adjacent to vast rural belt encompassing Naxalbari area where he spent his entire political life —minus 25 years of jail life, fighting relentlessly to uphold the rights of life and livelihood of the hapless and helpless Adivasi Tea garden workers and peasants subjected to ruthless exploitation by the tea planters and jotedars and usurers. A devout admirer of Netaji Subhas Ch Bose in his teens, Kanu Sanyal got interested about the communists and communist party when the then Congress government banned the party. He came in touch with Rakhal Majumder, Sunil Sarker, and some other party activists of the Siliguri Town and became a member of the Janaraksha Committee. It was the communist party influenced Janaraksha Committee that hit upon the plan to organize a protest demonstration against the then visiting chief Minister Dr Bidhan Ch Roy by waving black flag. The demonstration was organized as a mark of protest against the killings of party members Latika, Prativa, Amiya and Geeta by the police when they were leading a peaceful rally in Kolkata demanding revoking the ban imposed on communist party. -

Calcutta Notebook

Frontier Vol. 44, No. 41, April 22-28, 2012 Calcutta Notebook DRC TWO FASCINATING BOOKS before me—Ei Samayer Dolil O Anyanyo and Haate Khori. The books published from Kolkata in 2011, are written by Ashim Chattopadhyay. The first is a collection of newspaper post-edits mainly on political subjects, ranging in time from 1993 to 2011. The second is an autobiographical sketch of boyhood. Here, today, there will only be space enough to talk about the first. Ashim Chattopadhyay, Kaka, is well-known as a firebrand leader of the Naxalite movement and the CPI(ML) of the sixties. The post-edit series in question brings to the fore his command over language, written and spoken. His Bangla prose is flowing and resonant, uncluttered by too much ornament, yet facile and crystalline. The times were turbulent in the east. The old communist movement renounced and again embraced by Kaka was floundering with its capitalist baggage, and the CPI(M), the focus of his attention after the Naxalite episode, had initiated a characteristically arrogant and overbearing programme of snatching land, even prime agricultural land bearing three to four crops a year, from farmers, for industrial use. While this was a predictable outcome of some 30 years in government by sarkari communists, the Naxalite policy of individual killing of "class enemies", opponents and competitors had fractured and almost decimated the party of revolution in Bengal. The basic revolutionary ideas thrown up by Naxalbari had, however, entered the universe of discourse of the people, and from the struggles of the forest-dwellers and peasants in Andhra, Chattisgarh, Dandakaranya, Bihar and Jharkhand, emerged the CPI(Maoist) as a successor to the CPI(ML).