Govind Nihalani's 'Hazaar Chaurasi Ki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber

Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber TAILORING EXPECTATIONS How film costumes become the audience’s clothes ‘Bollywood’ film costume has inspired clothing trends for many years. Female consumers have managed their relation to film costume through negotiations with their tailor as to how film outfits can be modified. These efforts have coincided with, and reinforced, a semiotic of female film costume where eroticized Indian clothing, and most forms of western clothing set the vamp apart from the heroine. Since the late 1980s, consumer capitalism in India has flourished, as have films that combine the display of material excess with conservative moral values. New film costume designers, well connected to the fashion industry, dress heroines in lavish Indian outfits and western clothes; what had previously symbolized the excessive and immoral expression of modernity has become an acceptable marker of global cosmopolitanism. Material scarcity made earlier excessive costume display difficult to achieve. The altered meaning of women’s costume in film corresponds with the availability of ready-to-wear clothing, and the desire and ability of costume designers to intervene in fashion retailing. Most recently, as the volume and diversity of commoditised clothing increases, designers find that sartorial choices ‘‘on the street’’ can inspire them, as they in turn continue to shape consumer choice. Introduction Film’s ability to stimulate consumption (responding to, and further stimulating certain kinds of commodity production) has been amply explored in the case of Hollywood (Eckert, 1990; Stacey, 1994). That the pleasures associated with film going have influenced consumption in India is also true; the impact of film on various fashion trends is recognized by scholars (Dwyer and Patel, 2002, pp. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

Interview with Govind Nihalani Rukmavati Ki Haveli:: Creating

REVISTA CIENTÍFICA DE CINE Y FOTOGRAFÍA E-ISSN 2172-0150 Nº 12 (2016) INTERVIEW WITH GOVIND NIHALANI RUKMAVATI KI HAVELI: CREATING EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPES Amparo Rodrigo Mateu University of Mumbai, India [email protected] 25 years after filming Rukmavati Ki Haveli (1991), the Hindi movie adaptation of Lorca's play La casa de Bernarda Alba (Federico García Lorca, 1936), Mumbai-based Indian filmmaker and former cameraman Govind Nihalani (Karachi, 1940) vividly remembers the effect it had on him and relates how he adapted the play from Lorca's Spanish Andalusia to a film with an Indian background. 1 -Why did you choose Lorca and, among all his works, what attracted you to La casa de Bernarda Alba? I always liked theater and I was very close to a well-known Hindi theatre director. His name was Satyadev Dubey. He used to do English plays and he spoke to me a lot about some plays from Europe. Among them, he spoke about Lorca and this particular play. I had not read it but he described it as a strong play, so I became curious. I bought an English translation and I read it. I liked FOTOCINEMA, nº 13 (2016), E-ISSN: 2172-0150 321 the play very much because of its theme: authoritarianism and the rebellion against authoritarianism. I read it, I liked it and, then, I forgot about it. One day, I went to Jaisalmer, in Rajasthan. As I was going up the fort, I saw a group of Rajasthani women walking down. All of them -they must have been a particular tribe- were dressed in brown petticoats, brown skirts and black duppatas1 and chadars2, and wearing old silver jewelery. -

Reflections of Radical Political Movements on the Silver Screen: an Analysis

Global Media Journal-Indian Edition; Volume 12 Issue1; June 2020. ISSN:2249-5835 Reflections of Radical Political Movements on the Silver Screen: An Analysis Aakash Shaw Assistant Professor and Head, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication Vivekananda College (Affiliated to the University of Calcutta) [email protected] Abstract Jean – Louis Comolli and Jean Narboni described film as a particular product, manufactured within given economic relations, and involving labour to produce. This is a condition to which ‘independent film-makers’ and the ‘new cinema’ are subject, involving a number of workers and as a material product it is also considered as an ideological product of the system. No film makers can by individual efforts, change the economic relations governing the manufacture and distribution of her/his films. The radical political movements which culminated from the peasant uprising in 1967, spread like firestorm and eventually turned out to be an urban phenomenon. Films invoke current evaluations founded upon new criteria which are marked by the representation of power structures, authoritative institutions, engaging contestations and ideological apparatuses frozen in a specific time and space. Film reproduces reality that is an expression of prevailing ideology and seeks to re-interpret or find inferences and possible explications of the discourse from the past. In the context of radical political movements, the paper seeks to understand and analyze cinematic portrayal of Naxalite movement not only as peasants uprising but as a socio-economic approach arising as a response to the exploitation and subjugation prevalent in the semi-feudal and semi-colonial socio-economic structure. -

Analysing Structures of Patriarchy

LESSON 1 ANALYSING STRUCTURES OF PATRIARCHY Patriarchy ----- As A Concept The word patriarchy refers to any form of social power given disproportionately to men. The word patriarchy literally means the rule of the Male or Father. The structure of the patriarchy is always considered the power status of male, authority, control of the male and oppression, domination of the man, suppression, humiliation, sub-ordination and subjugation of the women. Patriarchy originated from Greek word, pater (genitive from patris, showing the root pater- meaning father and arche- meaning rule), is the anthropological term used to define the sociological condition where male members of a society tend to predominates in positions of power, the more likely it is that a male will hold that position. The term patriarchy is also used in systems of ranking male leadership in certain hierarchical churches and ussian orthodox churches. Finally, the term patriarchy is used pejoratively to describe a seemingly immobile and sclerotic political order. The term patriarchy is distinct from patrilineality and patrilocality. Patrilineal defines societies where the derivation of inheritance (financial or otherwise) originates from the father$s line% a society with matrilineal traits such as Judaism, for example, provides, that in order to be considered a Jew, a person must be born of a Jewish mother. Judaism is still considered a patriarchal society. Patrilocal defines a locus of control coming from the father$s geographic/cultural community. Most societies are predominantly patrilineal and patrilocal, but this is not a universal but patriarchal society is characteri)ed by interlocking system of sexual and generational oppression. -

Coalition Between Politics & Entertainment in Hindi Films: A

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Coalition between Politics & Entertainment in Hindi Films: A Discourse Analysis Dr. C. M. Vinaya Kumar Assistant Professor & Head Department of Journalism and Mass Communication Krishna University Machilipatnam-521 001 91-9985085530 Romesh Chaturvedi Sr. Lecturer Amity School of Communication Amity University, Lucknow Campus Uttar Pradesh, 91-9721964685 India Shruti Mehrotra Sr. Lecturer Amity School of Communication Amity University, Lucknow Campus Uttar Pradesh, India 91-9451177264 Abstract The study attempts to explore dynamics of political discourse as reflected in Hindi films. Political messages in most Hindi films are concealed within entertainment. Films use thrilling & entertaining plots mixed with political content in order to convey their messages to the public. Films not only reflect reality but also construct the political ideology. The public is generally unaware of the extent to which they are being influenced, managed and conditioned by the political discourses in Hindi films. This study attempts to conduct the discourse analysis on the Hindi film “Chakravyuh” to find how politics and entertainment are merged together to influence public opinion. The film is based on the dark, largely-unexposed world of the Naxalites fighting for their land and dignity. Discourse analysis of the film will help in exploring how an entertaining film can carry a meaningful message. For over 40 years in India, since the emergence of the Naxalite rebellion, cinema has drawn inspiration from the rupture caused by this iconic movement in Indian political history. Hindi films seem to have woken up to Naxalism, or Maoism, as it is more commonly known today. -

Preuzmi Publikaciju (PDF)

reuters Goran Tomašević / Goran Tomašević Prosvjednik stoji pred barikadom u plamenu za vrijeme demonstracija u Kairu 28. siječnja 2011. Policija i demonstranti vodili su bitke na ulicama Kaira u petak na četvrti dan nezapamćenih prosvjeda desetaka tisuća Egipćana koji su zahtijevali kraj vladavine predsjednika Hosnija Mubaraka, koja je trajala trideset godina. reuters Goran Tomašević / Goran Tomašević Pristaša oporbe maše cipelom u znak nepoštovanja, nedugo nakon klanjanja molitve petkom na Trgu Tahrir u Kairu 4. veljače 2011. Desetci tisuća Egipćana klanjali su u petak na kairskom Trgu Tahrir (Trg oslobođenja) za kraj tridesetogodišnje vladavine predsjednika Hosnija Mubaraka, u nadi da će im se pridružiti još milijun građana na dan koji su nazvali “Danom odstupanja.” reuters Goran Tomašević / Goran Tomašević Mubarakovi pristaše marširaju prema anti-vladinim prosvjednicima na Trgu Tahrir u Kairu 2. Veljače 2011. Protivnici i pristaše egipatskog predsjednika Hosnija Mubaraka borili su se šakama, kamenjem i palicama u Kairu u srijedu u sukobu koji je, izgleda, bio pokušaj snaga vjernih egipatskom vođi da okončaju prosvjede kojima se zahtijeva njegova ostavka. reuters Goran Tomašević / Goran Tomašević Pristaše oporbe klanjaju molitvu petkom pokraj tenkova pred pedsjedničkom palačom u Kairu 11. veljače 2011. Razgnjevljeni odlučnošću predsjednika Hosnija Mubaraka da ostane na vlasti, Egipćani marširaju u znak protesta pred njegovom palačom u Kairu, odbacujući jamstvo vojske za prijelaz na slobodne izbore ocjenivši taj korak nedovoljnim. reuters -

30122003 Dt Mpr 10 D L C

DLD‰‰†‰KDLD‰‰†‰DLD‰‰†‰MDLD‰‰†‰C 1 0 BACK BEAT DELHI TIMES, THE TIMES OF INDIA TUESDAY 30 DECEMBER 2003 based Puneet Sira, the film Sohail s Pak influence... stars Sohail Khan with Pak- Fardeen-Bebo ohail Khan has launched his own ban- istani actress Heena.The Sner and is ready with his first production film has music by Daboo are back! I Proud to be An Indian. Directed by London- Malik and KC Lord. (ANI) fter Thakshak, director A Govind Nihalani is ready with his next film Dev. The film stars industry heavy weights like Amitabh Bachchan, Om Puri, Fardeen Khan and Kareena Kapoor in lead roles. The film is three months ahead of its scheduled time. Apparently Amitabh had bulk dates on hand which he offered to Ni- halani and the director im- mediately rearranged the dates of his other stars and got busy shooting for his film. So Dev will be ready for re- lease in a couple of months. (ANI) Good innings wo years ago, director Anubhav Sinha’s debut film, T Tum Bin starring Priyanshu Chatterjee and San- dali Sinha in lead roles was a big hit. However, his next film Aaapko Pehle Bhi Dekha Hai for T-Series was a com- plete box-office dud. Anubhav will direct a film again for T Series that will hit the theatres in the near future. It will feature Gautam Rode in the lead role. He had made his de- but last year with Annarth. Gautam is the same guy who played the arrogant tourist in the popular Coca Cola ad that had Aamir Khan as a Nepali guide. -

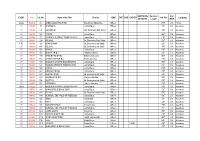

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

Analyzing Imtiaz Ali As an Auteur

Amity Journal of Media & Communication Studies (ISSN 2231 – 1033) Copyright 2017 by ASCO 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Amity University Rajasthan Analyzing Imtiaz Ali as an Auteur Kanika Kachroo Arya Dnyanasadhana College, Mumbai University, India Abstract Imtiaz Ali is a contemporary Bollywood director whose genre is love stories. He has a stream of experimental love stories to his credit, some bench markers are Jab We Met, Rockstar and Tamasha. Not only is his storytelling a well nurtured individualistic style, but the use of techniques of cinema are also experimental. My research paper will analyse this director in the boundaries of Auteur theory. The research will be a qualitative study and methodology used will be in-depth interviews and observation and use of secondary research resources to build up affirmation towards my hypothesis. This director’s style will be compared with other stalwarts of the genre like Raj Kapoor and Yash Chopra. This will carve out his style more specifically. Imtiaz Ali has a unique style aesthetically as well as technically. He understands the psychology of his target audience and that’s what has carved a niche for him in Bollywood - a cult director of romance genre. Key words: Auteur Theory, Direction, Niche, Bollywood. Introduction Imtiaz Ali is one amongst the contemporary directors of Bollywood. His directorial debut was Socha Na Tha released in 2005. Though the movie did not do well but he received a lot of critical acclaim for it. Jab we Met (2007) and Rockstar (2011) brought him into limelight. Jab We Met was a box office success and Rockstar was appreciated in critical circles for superb rendition of a careless musician. -

1 Sample Question Paper on Cinema Prepared by : Naresh Sharma: Director

1 Sample question paper on cinema prepared by : Naresh Sharma: Director. CRAFT Film School.Delhi.www.craftfilmschool.com: [email protected] Disclaimer about this sample paper ( 50+28 Objective questions ) by Naresh Sharma: 1. This is to clarify that I, Naresh Sharma, neither was nor is a part of any advisory body to FTII or SRFTI , the authoritative agencies to set up such question paper for JET-2018 entrance exam or any similar entrance exam. 2. As being a graduate of FTII, Pune, 1993, and having 12 years of Industry experience in my quiver as well the 12 years of personal experience of film academics, as being the founder of CRAFT FILM SCHOOL, this sample question-answers format has been prepared to give the aspiring students an idea of variety of questions which can be asked in the entrance test. 3. The sample question paper is mainly focused on cinema, not in exhaustive list but just a suggestive list. 4. As JET - 2018 doesn't have any specific syllabus, so any question related to General Knowledge/Current Affair can be asked. 5. Since Cinema has been an amalgamation of varied art forms, Entrance Test intends to check as follows; a) Information; and b) Analysis level of students. 6. This sample is targeted towards objective question-answers, which can form part of 20 marks. One need to jot down similar questions connected with Literature/ Panting Music/ Dance / Photography/ Fine arts etc. For any Query, one can write: [email protected] 2 Sample question paper on cinema prepared by : Naresh Sharma: Director.