Cultivating Development: Trends and Opportunities at the Intersection of Food and Real Estate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delve Deeper Into Food, Inc a Film by Robert Kenner

Delve Deeper into Food, Inc A film by Robert Kenner This multi-media resource list, Public Affairs, 2009. Expanding Second Nature: A Gardener's compiled by Susan Conlon and on the film’s themes, the book Education (1991). Martha Perry of the Princeton Food, Inc. will answer those Public Library, includes books, questions through a series of Richardson, Jill. Recipe for films and other materials challenging essays by leading America: Why Our Food System related to the issues presented experts and thinkers. This book will is Broken and What We Can Do in the film Food, Inc. encourage those inspired by the to Fix It. Ig Publishing, 2009. film to learn more about the issues, Food activist Jill Richardson shows In Food, Inc., filmmaker Robert and act to change the world. how sustainable agriculture—where Kenner lifts the veil on our nation's local farms raise food that is food industry, exposing the highly Hamilton, Lisa M. Deeply healthy for consumers and animals mechanized underbelly that's been Rooted: Unconventional and does not damage the hidden from the American consumer Farmers in the Age of environment—offers the only with the consent of our Agribusiness. Counterpoint, solution to America’s food crisis. In government's regulatory agencies, 2009. Journalist and photographer addition to highlighting the harmful USDA and FDA. Our nation's food Hamilton presents a multicultural conditions at factory farms, this supply is now controlled by a snapshot of the American timely and necessary book details handful of corporations that often sustainable agriculture movement, the rising grassroots food put profit ahead of consumer profiling a Texas dairyman, a New movement, which is creating an health, the livelihood of the Mexican rancher and a North agricultural system that allows American farmer, the safety of Dakotan farmer, all who have people to eat sustainably, locally, workers and our own environment. -

Preserving California's History and Lifelong Memories

2009-2010 ANNUAL REPORT Preserving California’s History AND LIFELONG MEMORIES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 2009-2010 in Review 9 The Organization - A Team with a Purpose 2 Mission Preservation Foundation 10 Our Volunteers - People with Passion 2-3 2009-2010 Lasting Accomplishments 11 Landmarks Club Members 4 Community Events Hosted in 2009-2010 11 Preserving California’s History 5 Traveling Exhibits 12-13 Financials 6-7 Educational Programming Accomplishments 14-20 Programs and Giving Opportunities in 2009-2010 8 Education Programs and Partners 21-38 2009-2010 Preservation Society Membership 8 Adopt-A-Class Program Supporters 26801 Ortega Highway, San Juan Capistrano, CA 92675 Mission San Juan Capistrano receives no sustaining support (949) 234-1300 www.missionsjc.com from any governmental agency or religious organization. A non-profit organization under IRS 501 (c) (3) Mission Preservation Foundation IRS 501 (c) (3) Interior Photo Credits: Val Westover Photography Tax ID #33-0833283 Diocesan IRS 501 (c) (3). ID #95-1904079 Joe Broccardo Photography 2009-2010 MAKING HISTORY AT MISSION SAN JUAN CAPISTRANO Over the last twelve months Mission San Juan Capistrano We welcome all who come in peace to return time and time continued to provide meaningful learning opportunities, again to rediscover California history here, at Orange County’s community and cultural events, one-of-a-kind experiences, birthplace and only mission. Thank you for your support and served as a historic landmark welcoming people from all during this past fiscal year. over the world. Sincerely, As a center for student education in social studies, over 52,000 George O’Connell, President students received a special day of hands on learning and left The Mission Preservation Foundation with a new appreciation of history. -

Meet Your Police Chief

VOLUME FOUR, NUMBER THIRTY-FOUR MISSION VIEJO, CALIFORNIA April 2018 A SPECIAL TRIBUTE FOR A VERY LOVED SON The Mission Viejo Reporter promises fast, fair, and accurate reporting. If for any reason we fail to live up to these promises, please don't tell anyone. Questions or Comments: 949.364.2309 • [email protected] MEETMISSION YOUR VIEJO'S POLICE TOP CHIEF COP COVER PHOTO: Jim Dante at La Paws Dog Park CITY SPEAK Mission Viejo Reporter....................364-2309 Kwik Kopy Printing..........................364-2309 MISSION VIEJO REPORTER Emergency Numbers Police Services / Fire Services....................911 HITSBack in the 1960's and 1970's, HOME the Mission Viejo Reporter was partRUN of our community. The Reporter ceased operations in the 80's but, thanks to Kwik Kopy Printing owner and former Mission Police Service (Non Emergency)........770-6011 Viejo mayor Dave Leckness, it's back, and better than ever. For the past three Suicide Hotline............................877-727-4747 years Dave has brought us great stories about people, local businesses and memories of our past. Throughout each issue you'll find local Mission Viejo Public Services businesses who advertise, I suggest you visit and buy from those companies. MV Animal Services...........................470-3045 One of the great benefits of the MVR is that it allows us Mission Viejo Pothole Hotline...................................470-8405 councilmembers to express our feelings and share information with you the Graffiti Hotline.....................................470-2924 residents in a publication that gets delivered directly to your homes. Living and raising our families in Mission Viejo is something we are all proud Helpful Numbers by Greg Raths of and as your Mayor Pro Tem, I encourage you to contact me with your concerns Mayor Pro-Tem, Mission Viejo or suggestions to make our city a better place. -

Combatting Monsanto

Picture: Grassroots International Combatting Monsanto Grassroots resistance to the corporate power of agribusiness in the era of the ‘green economy’ and a changing climate La Via Campesina, Friends of the Earth International, Combat Monsanto Technical data name: “Combatting Monsanto Grassroots resistance to the corporate power of agribusiness in the era of the ‘green economy’ and a changing climate” author: Joseph Zacune ([email protected]) with contributions from activists around the world editing: Ronnie Hall ([email protected]) design and layout: Nicolás Medina – REDES-FoE Uruguay March 2012 Combatting Monsanto Grassroots resistance to the corporate power of agribusiness in the era of the ‘green economy’ and a changing climate INDEX Executive summary / 2 Company profile - Monsanto / 3 Opposition to Monsanto in Europe / 5 A decade of French resistance to GMOs / 6 Spanish movements against GM crops / 9 German farmers’ movement for GM-free regions / 10 Organising a movement for food sovereignty in Europe / 10 Monsanto, Quit India! / 11 Bt brinjal and biopiracy / 11 Bt cotton dominates cotton sector / 12 Spiralling debt still triggering suicides / 12 Stopping Monsanto’s new public-private partnerships / 13 Resistance to Monsanto in Latin America / 14 Brazilian peasant farmers’ movement against agribusiness / 14 Ten-year moratorium on GM in Peru / 15 Landmark ruling on toxic soy in Argentina / 15 Haitians oppose seed aid / 16 Guatemalan networks warn of new biosafety proposals / 17 Battle-lines drawn in the United States / 17 Stopping the -

ULI: Returns on Resilience the Business Case

Returns on Resilience THE BUSINESS CASE Cover photo: A view of the green roof and main office tower at 1450 Brickell Avenue, with Biscayne Bay beyond. Robin Hill © 2015 Urban Land Institute 1025 Thomas Jefferson Street, NW Suite 500 West Washington, DC 20007-5201 All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission of the copyright holder is prohibited. Recommended bibliographic listing: Urban Land Institute: Returns on Resilience: The Business Case. ULI Center for Sustainability. Washington, D.C.: the Urban Land Institute, 2015. ISBN: 978-0-87420-370-7 Returns on Resilience THE BUSINESS CASE Project Director and Author Sarene Marshall Primary Author Kathleen McCormick This report was made possible through the generous support of The Kresge Foundation. Center for Sustainability About the Urban Land Institute The mission of the Urban Land Institute is to provide leadership in the responsible use of land and in creating and sustaining thriving communities worldwide. Established in 1936, the Institute today has more than 35,000 members worldwide representing the entire spectrum of the land use and development disciplines. ULI relies heavily on the experience of its members. It is through member involvement and information resources that ULI has been able to set standards of excellence in development practice. The Institute has long been recognized as one of the world’s most respected and widely quoted sources of objective information on urban planning, growth, and development. ULI SENIOR -

Table of Contents

City of Encinitas DRAFT SIXTH CYCLE HOUSING ELEMENT APPENDIX B Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... i Appendix B: Housing Profile Report ...................................................................................... 1 1 Population Characteristics ............................................................................................... 1 1.1 Population Growth ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Age Characteristics ...................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Race/Ethnicity Characteristics ..................................................................................... 2 1.4 Employment ................................................................................................................. 4 1.5 Commuting Patterns .................................................................................................... 6 2 Household Characteristics ............................................................................................... 7 2.1 Household Type and Size ............................................................................................ 8 2.2 Household Income ......................................................................................................10 3 Housing Problems ...........................................................................................................12 -

Agrihoods: Development-Supported Agriculture

!"#$%&$'("%)"*+,"-'*.%/'0"1,/*,$")%$"!##$%#$.'*,"2,3+/%0%&4""5""678997:;<7=6;9""5"">>>?'**$'?/3'*?%$& Agrihoods: Development-Supported Agriculture By Jef Birkby This publication introduces the concept of development-supported agriculture, also known as agrihoods. NCAT Smart Growth The recent growth of agrihoods in the United States is discussed. The major types of agrihoods are Specialist described, and the benef ts and challenges of agrihood development are discussed. Case studies of Published June 2016 agrihoods are presented, and further agrihood resources are included. ©NCAT IP515 Contents Introduction: What are Agrihoods? .................1 Types of Agrihoods ..........................2 Inf ll Development and Agrihoods ..................3 Benef ts of Agrihoods ..........................3 Challenges and Concerns of Agrihoods ..........................5 Conclusion .........................6 Appendix: 12 Agrihoods Taking Farm-to-Table Living Mainstream ..........7 References .........................9 Farmers Market at Willowsford Farms. Photo Credit: Molly Peterson Further Resources ...........9 Introduction—What are Agrihoods? he popularity of planned suburban Although this type of mass-produced subdivision home developments in the United States has been popular for decades, residents of these stretches back to the 1950s. Many sol- cookie-cutter housing developments often felt iso- Tdiers returning from World War II were anxious lated from their neighbors due to the subdivision ATTRA (www.attra.ncat.org) to acquire a home and start -

Foods of the Future

3/3/2017 Foods of the Future Mary Lee Chin Nutrition Edge Communications Minnesota Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics Minneapolis Marriott Northwest Brooklyn Park, MN April 27, 2017 Photo credit: pixabay.com Mary Lee Chin MS RDN Foods of the Future @maryleechin Disclosure Sponsor FCP • Family • A bowl of rice Background: • Purdue Ag & Food security • Food industry- Monsanto Academy - RD Farmer • Organic co-op • CSA Refugees 1 3/3/2017 Session Objectives 1. Identify at least one new food production technique on the horizon and discern its safety. 2. Describe the benefits of advancements in foods of the future. 3. Respond to the latest foods of the future with confidence to colleagues and consumers, appropriately address their concerns, and explain pros and cons in a clear and understandable way. Future of Food Initiative Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation Future of Food Resources for Members • Toolkits www.eatrightfoundation.org/toolkits-webinars • Hunger in Our Community. What We Can Do. • Smart Choices. For a Healthy Planet. (English/Spanish!) • Tossed Treasures. How We All Can Waste Less Food. (English/Spanish!) • Supervised Practice Concentrations: • Food Insecurity and Food Banking—available now! www.healthyfoodbankhub.org • Food Systems—under development! • Webinars and Infographics www.eatrightfoundation.org • Affiliate Presentations: • “Changing the Way We Look at Agriculture” 32 affiliates/DPGs (2015) • Food waste, food additives, and GMO presentations 10 affiliates (2016) • Foods of future, farming tools, and food preservation presentations 10 affiliates (2017) 2 3/3/2017 Last year our donors’ generosity helped us award: $446,900 in student scholarships to 194 students $14,000 in student stipends to help 140 students attend FNCE. -

See Food Innovation with a Whole New Lens

See food innovation with a whole new lens. Virtual Event and Expo July 13-15, 2020 iftevent.org 1 SHIFT20 Program Overview Food innovation is evolving at a rapid pace, consumer perceptions are evolving, and the IFT community is leading the way. Accelerating the science of food and technology to sustainably feed and nourish the world’s population is the mission of IFT and nowhere is this more evident than when we come together through IFT20s virtual experience to share, imagine, and collectively solve challenges impacting our global food supply. But in order to do this, we need to approach innovation differently, we need to challenge the status quo, and we need to cross disciplines to gain new insights and shift our thinking to bring the world better food. IFT20 is where this shift begins. 2 Featured Speakers April Rinne Monday, July 13 SHIFT20 Virtual Event and Expo will kick off with a thought- provoking keynote address with April Rinne, member of the World Economic Forum, speaker, writer, and authority on the new economy, future of work, and global citizenship. The world is changing, and April has spent her career making sense of these changes from the perspective of a trusted advisor, advocate, thought leader and lifelong global citizen. With more than 20 years and 100 countries of experience at the 50-yard line of emerging innovation, April brings a keen eye towards where the world is heading with no greater purpose than to help build a brighter tomorrow. In this keynote April will explore the critical role that food science, emerging technologies, and the food industry will need to play in addressing food security in the face of our current pandemic times and global climate change. -

APPRAISAL of Willowick Golf Course 3017 W. 5Th

APPRAISAL OF Willowick Golf Course 3017 W. 5th Street Santa Ana, California Date of Value: Submitted To: February 24, 2021 Omar Sandoval Woodruff, Spradlin & Smart Date of Report: 555 Anton Boulevard, Suite 1200 Costa Mesa, CA 92626 April 13, 2021 Submitted By: Our File No.: George Hamilton Jones, Inc. 221-3 Stuart D. DuVall, MAI Casey O. Jones, MAI April 13, 2021 Omar Sandoval, Esq. Woodruff, Spradlin & Smart 555 Ant on Boulevard, Suite 1200 Costa Mesa, CA 92626 Re: Appraisal of the Willowick Golf Course Property Dear Mr. Sandoval: In accordance with your request and authorization, I have formed an opinion of the market value of the fee interest in the 101.5-acre Willowick Golf Course, located in the City of Santa Ana, California. As the following Appraisal Report will present, my judgment of the highest and best use of the subject property is for development to a master-planned community. This appraisal is based upon the extraordinary assumption that the utility and value of the appraised property is subject to the Surplus Land Act and Government Code Government Code 54233, which states that if 10 or more residential units are developed, then 15 percent of the total number of units must be dedicated to affordable housing. The date of value of this appraisal is February 24, 2021. As a result of my inspection of the subject property, investigation of various comparable data, market studies and valuation analyses I concluded that, as of February 24, 2021, the market value of the appraised property was $90,000,000. Market Value Conclusion: $90,000,000 George Hamilton Jones, Inc. -

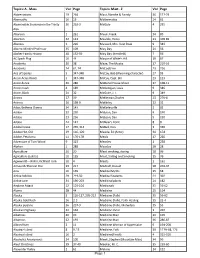

California Folklore Miscellany Index

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Thomas Blum and William Knitz

Oral History Interview with Thomas C. Blum and W.W. “Bill” Knitz Date: Saturday, January 28, 2012 Interviewer: Robert David Breton Location: Mission Viejo Library Mission Viejo, California This is a transcript of a video-recorded interview conducted by the Mission Viejo Library and funded by a Library Services and Technology Act grant administered by the California State Library. The initial, verbatim transcript of the interview was sent to the interviewee to give him or her an opportunity to check it for typographical errors, to correct any gross inaccuracies of recollection, and to make minor emendations. This is the edited version of the original transcript, but the original video recording of the interview has not been altered. The reader should remember that this is a transcript of the spoken, rather than the written, word. The interview must be read with an awareness that different persons’ memories about an event will often differ. The reader should take into account that the answers may include personal opinions from the unique perspective of the interviewee and that the responses offered are partial, deeply involved, and certainly irreplaceable. A limited number of visual and audio data from this copyrighted collection of oral histories may be used for personal study, private scholarship or research, and scholastic teaching under the provisions of United States Code, Title 17, Section 107 (Section 107), which allows limited “fair use” of copyrighted materials. Such “fair use” is limited to not-for-profit, non-commercial, educational purposes and does not apply to large amounts or “substantial” portions in relation to the transcript as a whole, within the meaning of Section 107.