Thomas Blum and William Knitz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preserving California's History and Lifelong Memories

2009-2010 ANNUAL REPORT Preserving California’s History AND LIFELONG MEMORIES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 2009-2010 in Review 9 The Organization - A Team with a Purpose 2 Mission Preservation Foundation 10 Our Volunteers - People with Passion 2-3 2009-2010 Lasting Accomplishments 11 Landmarks Club Members 4 Community Events Hosted in 2009-2010 11 Preserving California’s History 5 Traveling Exhibits 12-13 Financials 6-7 Educational Programming Accomplishments 14-20 Programs and Giving Opportunities in 2009-2010 8 Education Programs and Partners 21-38 2009-2010 Preservation Society Membership 8 Adopt-A-Class Program Supporters 26801 Ortega Highway, San Juan Capistrano, CA 92675 Mission San Juan Capistrano receives no sustaining support (949) 234-1300 www.missionsjc.com from any governmental agency or religious organization. A non-profit organization under IRS 501 (c) (3) Mission Preservation Foundation IRS 501 (c) (3) Interior Photo Credits: Val Westover Photography Tax ID #33-0833283 Diocesan IRS 501 (c) (3). ID #95-1904079 Joe Broccardo Photography 2009-2010 MAKING HISTORY AT MISSION SAN JUAN CAPISTRANO Over the last twelve months Mission San Juan Capistrano We welcome all who come in peace to return time and time continued to provide meaningful learning opportunities, again to rediscover California history here, at Orange County’s community and cultural events, one-of-a-kind experiences, birthplace and only mission. Thank you for your support and served as a historic landmark welcoming people from all during this past fiscal year. over the world. Sincerely, As a center for student education in social studies, over 52,000 George O’Connell, President students received a special day of hands on learning and left The Mission Preservation Foundation with a new appreciation of history. -

Meet Your Police Chief

VOLUME FOUR, NUMBER THIRTY-FOUR MISSION VIEJO, CALIFORNIA April 2018 A SPECIAL TRIBUTE FOR A VERY LOVED SON The Mission Viejo Reporter promises fast, fair, and accurate reporting. If for any reason we fail to live up to these promises, please don't tell anyone. Questions or Comments: 949.364.2309 • [email protected] MEETMISSION YOUR VIEJO'S POLICE TOP CHIEF COP COVER PHOTO: Jim Dante at La Paws Dog Park CITY SPEAK Mission Viejo Reporter....................364-2309 Kwik Kopy Printing..........................364-2309 MISSION VIEJO REPORTER Emergency Numbers Police Services / Fire Services....................911 HITSBack in the 1960's and 1970's, HOME the Mission Viejo Reporter was partRUN of our community. The Reporter ceased operations in the 80's but, thanks to Kwik Kopy Printing owner and former Mission Police Service (Non Emergency)........770-6011 Viejo mayor Dave Leckness, it's back, and better than ever. For the past three Suicide Hotline............................877-727-4747 years Dave has brought us great stories about people, local businesses and memories of our past. Throughout each issue you'll find local Mission Viejo Public Services businesses who advertise, I suggest you visit and buy from those companies. MV Animal Services...........................470-3045 One of the great benefits of the MVR is that it allows us Mission Viejo Pothole Hotline...................................470-8405 councilmembers to express our feelings and share information with you the Graffiti Hotline.....................................470-2924 residents in a publication that gets delivered directly to your homes. Living and raising our families in Mission Viejo is something we are all proud Helpful Numbers by Greg Raths of and as your Mayor Pro Tem, I encourage you to contact me with your concerns Mayor Pro-Tem, Mission Viejo or suggestions to make our city a better place. -

APPRAISAL of Willowick Golf Course 3017 W. 5Th

APPRAISAL OF Willowick Golf Course 3017 W. 5th Street Santa Ana, California Date of Value: Submitted To: February 24, 2021 Omar Sandoval Woodruff, Spradlin & Smart Date of Report: 555 Anton Boulevard, Suite 1200 Costa Mesa, CA 92626 April 13, 2021 Submitted By: Our File No.: George Hamilton Jones, Inc. 221-3 Stuart D. DuVall, MAI Casey O. Jones, MAI April 13, 2021 Omar Sandoval, Esq. Woodruff, Spradlin & Smart 555 Ant on Boulevard, Suite 1200 Costa Mesa, CA 92626 Re: Appraisal of the Willowick Golf Course Property Dear Mr. Sandoval: In accordance with your request and authorization, I have formed an opinion of the market value of the fee interest in the 101.5-acre Willowick Golf Course, located in the City of Santa Ana, California. As the following Appraisal Report will present, my judgment of the highest and best use of the subject property is for development to a master-planned community. This appraisal is based upon the extraordinary assumption that the utility and value of the appraised property is subject to the Surplus Land Act and Government Code Government Code 54233, which states that if 10 or more residential units are developed, then 15 percent of the total number of units must be dedicated to affordable housing. The date of value of this appraisal is February 24, 2021. As a result of my inspection of the subject property, investigation of various comparable data, market studies and valuation analyses I concluded that, as of February 24, 2021, the market value of the appraised property was $90,000,000. Market Value Conclusion: $90,000,000 George Hamilton Jones, Inc. -

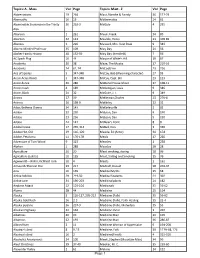

California Folklore Miscellany Index

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Cultivating Development: Trends and Opportunities at the Intersection of Food and Real Estate

CULTIVATING DEVELOPMENT Trends and Opportunities at the Intersection of Food and Real Estate Building Healthy Places Initiative On the cover: Investments in food-related enterprises within the context of real estate projects can support a developer’s bottom line, while also advancing health and sustainability goals. (© SeanShot/iStock) © 2016 by the Urban Land Institute 2001 L Street, NW Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036 Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission of the copyright holder is prohibited Recommended bibliographic listing: Urban Land Institute. Cultivating Development: Trends and Opportunities at the Intersection of Food and Real Estate. Washington, D.C.: Urban Land Institute, 2016. ISBN: 978-0-87420-394-3 CULTIVATING DEVELOPMENT Trends and Opportunities at the Intersection of Food and Real Estate Building Healthy Places Initiative ABOUT THE URBAN LAND INSTITUTE The Urban Land Institute is a nonprofit research and education organization whose mission is to provide leadership in the responsible use of land and in creating and sustaining thriving communities worldwide. Established in 1936, the Institute today has more than 39,000 members and associates from 82 countries, representing the entire spectrum of the land use and development disciplines. ULI relies heavily on the experience of its members. It is through member involvement and information resources that ULI has been able to set standards of excellence in development practice. The Institute is recognized internationally as one of America’s most respected and widely quoted sources of objective information on urban planning, growth, and development. -

Ladera Ranch

LADERA RANCH Orange County, California Development Team A scenic, view-oriented, environmentally responsible community that strikes a careful balance between Owners/Developers preserving natural resources and providing much-needed housing, Ladera Ranch, which was begun in 1998 and substantially completed in 2006, is a 4,000-acre (1,619 ha) master-planned community carved Rancho Mission Viejo San Juan Capistrano, California out of southern California’s vast Rancho Mission Viejo. More than 1,600 acres (648 ha) of sensitive habi- www.RanchomissionViejo.com tat are being preserved as open space under a perpetual land trust, leaving about 2,400 acres (971 ha) to 2 DMB Consolidated Holdings, LLC be developed with 8,100 homes and 1 million square feet (92,900 m ) of commercial space in six villages Scottsdale, Arizona and three multiuse districts, with a relatively high average density—for production housing on a www.dmbinc.com greenfield site—of 7.1 units per acre (17.5/ha). A central biofiltration system collects and naturally treats low-flow stormwater runoff, while a centralized computer system tightly controls irrigation, reducing wa- Master Planner ter use. The community’s final two villages, Terramor and Covenant Hills, have incorporated a wide range EDAW, Inc. of pioneering green building techniques, making Ladera Ranch one of the largest concentrations of green- Irvine, California www.edaw.com designed and -constructed homes in the United States and the nation’s largest solar community. Reflecting the theme of “neighborhood as amenity,” Ladera Ranch is organized around a hierarchy Architect of community, village, and neighborhood planning goals. Its soft infrastructure and governance struc- William Hezmalhalch Architects, Inc. -

DRAFT CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY RANCHO MISSION VIEJO RIDING PARK PROJECT SAN JUAN CAPISTRANO, ORANGE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Gini

DRAFT CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY RANCHO MISSION VIEJO RIDING PARK PROJECT SAN JUAN CAPISTRANO, ORANGE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: City of San Juan Capistrano Joe Parco, City Engineer 32400 Paseo Adelanto San Juan Capistrano, CA 92675 Prepared by: Wood Environmental and Infrastructure Solutions 1845 Chicago Avenue, Suite D Riverside, California 92507 Gini Austerman, M.A., RPA – Principal Investigator Michael Amorelli – Project Archaeologist May 2019 Wood Project Number 5025170009 ©Wood Environment & Infrastructure. All Rights Reserved. Rancho Mission Viejo Riding Park Restoration Project Cultural Resource Inventory May 2019 Page i MANAGEMENT SUMMARY Wood Environmental & Infrastructure (Wood) was contracted to conduct an archaeological survey in support of environmental clearance of the proposed Rancho Mission Viejo Riding Park Restoration Project in San Juan Capistrano, Orange County, California. The proposed project consists of the long-term storm drain maintenance, restoration of the San Juan Creek banks, the removal of the Arizona Crossing and the installation of an underground storage vault for storm water treatment and discharge. The Project Area of Potential Effect (APE) includes the Rancho Mission Viejo Riding Park and spans both banks of the San Juan Creek immediately south of the California State Highway 74 (Ortega Highway). Specifically, the project is in Township 7 South, Range 7 West, Sections 32 and 33 as depicted in the U.S. Geological Survey Canada Gobernadora, California, 7.5’ quadrangle. The study is being conducted as a part of the environmental review process for the proposed project in accordance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The purpose of this study is to provide the U.S. -

Municipal Service Review & Sphere of Influence Study

Municipal Service Review & Sphere of Influence Study South Orange County Orange County Local Agency Formation Commission Municipal Service Review & Sphere of Influence Study for South Orange County (MSR 05-24) Draft December 2005 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ...............................................................................................................................I SECTION 1:.................................................................................................................1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................1 SECTION 2:.................................................................................................................9 AGENCY PROFILES ............................................................................................................................9 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................10 SECTION 3:...............................................................................................................25 GROWTH & PROJECTED POPULATION.....................................................................................25 A. REGIONAL SUMMARY ............................................................................................................26 B. EXISTING & PROJECTED POPULATION ................................................................................27 SECTION -

2015 Urban Water Management Plan

2015 URBAN WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN FINAL JUNE 2016 2015 URBAN WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2015 URBAN WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN Santa Margarita Water District FINAL Prepared for: Don Bunts Chief Engineer Santa Margarita Water District 26111 Antonio Pkwy Rancho Santa Margarita, CA 92688 Prepared by: Arcadis U.S., Inc. 445 South Figueroa Street Suite 3650 Sarina Sriboonlue, P.E. Los Angeles Staff Environmental Engineer California 90071 Tel 213 486 9884 Fax 213 486 9894 Our Ref.: 27704002.0000 Date: June 2016 arcadis.com 2015 URBAN WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN CONTENTS Acronyms and Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................... vii 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Urban Water Management Plan Requirements .......................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Agency Overview ........................................................................................................................ 1-3 1.3 Service Area and Facilities ......................................................................................................... 1-6 1.3.1 Santa Margarita Water District Service Area ................................................................... 1-6 1.3.2 Santa Margarita Water District Water Facilities ............................................................... 1-8 2 Demands ............................................................................................................................................ -

San Juan Capistrano Community History Project

San Juan Capistrano Community History ARBISO, Paul Anacleto (1895— ) O.H. 1464 Interviewer: Karen W. Tunnbull Date: December 30, 1975 Status: Completed 1976, 27 pp., index, photos Tape length: 60 min. A third generation resident is the caretaker for the San Juan Capistrano Mission and the official bell ringer who rings the bells when the swallows return each March and other special, historical events. Discusses ghosts, treasures, and other legends of the area including personal encounters with apparitions. BAUMGARTNER, John J., Jr. (1901— ) O.H. 1657 Interviewer: Shirley E. Stephenson Date: August 21, 1977; March 18, 1978 Status: Completed 1982, 193 pp. index, photos, appendixes Tape length: 5 hrs. 30 min. A section of the Rancho Santa Margarita y Las Flores, a large Mexican land grant formerly owned by the last Mexican governor Pio Pico, then by Juan Forster, reflects about life at the rancho during the days when Richard O’Neill, Sr., his grandfather, and James Flood jointly owned the land. The ranch often referred to as the O’Neill Ranch is located in southern Orange County and northern San Diego County of southern California. The Flood portion of Rancho Santa Margarita has been Camp Pendleton since World War II. Baumgartner resides in San Juan Bautista and is well known in the California livestock industry having served in an official capacity in several organizations including president of the California Cattlemen’s Association. Bound copy includes a copy of the original “Abstract of Title” of the Rancho Santa Margarita y Las Flores and other historical documents. CLARK, Robert S. (1944— ) O.H. -

Orange County Planning Contacts Guide, 2015

ORANGE COUNTY CONTACTS GUIDE ANAHEIM CHAMBER OF COMMERCE Acronym: Web site: http://www.anaheimchamber.org/ Type: Local Planning Area(s): Economic Development The Anaheim Chamber of Commerce links businesses with other leading Anaheim area business members, officers, leaders and managers, and elected officials to enhance economic growth and development. Through involvement in and attendance at chamber events, local business leaders are better connected with other business professionals outside of their regular schedule. The Chamber’s strategic initiatives include: Building a strong local economy; promoting and branding the Anaheim community; creating networking through business development opportunities; representing business interests in government; and political action. ASSOCIATION OF CALIFORNIA CITIES, ORANGE COUNTY Acronym: ACC-OC Web site: http://www.accoc.org/ Type: Local Planning Area(s): Economic Development, Employment, Infrastructure The Association of California Cities, Orange County (ACC-OC) was founded in 2011 as the hub for public policy for Orange County cities. ACC-OG serves as the regional advocate for local control, both locally and in Sacramento. It is a statewide and national model for creating good public policy from the ground up through its advocacy and education efforts. ACC-OG convenes leaders to develop solutions to the cities’ most pressing issues through numerous policy committees. BUILDING INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, ORANGE COUNTY CHAPTER Acronym: BIASC Web site: http://www.biasc.org/orange-county/ Type: Business Planning Area(s): Construction, Housing The Building Industry Association of Southern California, Inc. (BIASC), has been instrumental in helping the residential construction industry meet the region's demand for new housing. BIASC has nearly 1,000 primary members representing all professions associated with residential construction. -

RMV Downloadbook.Pdf

“Take care of the land, and the land will take care of you.” Marguerite (“Daisy”) O’Neill Throughout the decades, the O’Neill/Avery/Moiso family has remained steadfastly grounded to these words, keeping intact the remaining 23,000 acres of their family ranch known as Rancho Mission Viejo. Today, Rancho Mission Viejo is the last working ranch in Orange County, home to acres of citrus groves, miles of protected creeks and canyons within The Reserve at Rancho Mission Viejo, and soon, the final community taking shape amidst this splendor. Table of Contents The Ranch: Past and Present .................................................... 1 Community Development ......................................................... 5 Ranch Operations ................................................................... 12 Open Space Conservation ....................................................... 15 Civic Partnerships ................................................................... 20 Management Team ................................................................. 24 The Ranch: Past and Present “For sure, the blessings of landownership come with important responsibilities, including a commitment to manage thoughtfully the land, a pledge to honor family, friends and community as well as help meet the demands of a growing population, and a promise to always ‘make your handshake, your bond’.” Anthony R. Moiso President and Chief Executive Officer 1 Ranch History “The O’Neill family’s place in the history of Orange County and the state of California is marked by generations of enlightened community leadership. At Ranch Mission Viejo, the O’Neills keep alive the spirit and traditions of early California farming and cattle ranching. Nancy and I salute the O’Neills and the community in which they live.” President Ronald Reagan April 23, 1982 upon the centennial of Rancho Mission Viejo 1882 – 1910s Make your handshake your bond The story of Rancho Mission Viejo began in a deal struck with a handshake between fellow Irish immigrants, James Flood and Richard O’Neill, Sr.