I. Runes Notes on the History of Runes, Focusing on Historical Changes in Orthography and Pronunciation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT Savannah Dehart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF

ABSTRACT Savannah DeHart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF NORTHERN PAGAN RELIGIOSITY IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES. (Under the direction of Michael J. Enright) Department of History, May 2012. This thesis investigates the religiosity of some Germanic peoples of the Migration period (approximately AD 300-800) and seeks to overcome some difficulties in the related source material. The written sources which describe pagan elements of this period - such as Tacitus’ Germania, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and Paul the Deacon’s History of the Lombards - are problematic because they were composed by Roman or Christian authors whose primary goals were not to preserve the traditions of pagans. Literary sources of the High Middle Ages (approximately AD 1000-1400) - such as The Poetic Edda, Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda , and Icelandic Family Sagas - can only offer a clearer picture of Old Norse religiosity alone. The problem is that the beliefs described by these late sources cannot accurately reflect religious conditions of the Early Middle Ages. Too much time has elapsed and too many changes have occurred. If literary sources are unavailing, however, archaeology can offer a way out of the dilemma. Rightly interpreted, archaeological evidence can be used in conjunction with literary sources to demonstrate considerable continuity in precisely this area of religiosity. Some of the most relevant material objects (often overlooked by scholars) are bracteates. These coin-like amulets are stamped with designs that appear to reflect motifs from Old Norse myths, yet their find contexts, including the inhumation graves of women and hoards, demonstrate that they were used during the Migration period of half a millennium earlier. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

Nancy L. Wicker and Henrik Williams. Futhark 3

Futhark International Journal of Runic Studies Main editors James E. Knirk and Henrik Williams Assistant editor Marco Bianchi Vol. 3 · 2012 © Contributing authors 2013 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ All articles are available free of charge at http://www.futhark-journal.com A printed version of the issue can be ordered through http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-194111 Editorial advisory board: Michael P. Barnes (University College London), Klaus Düwel (University of Göttingen), Lena Peterson (Uppsala University), Marie Stoklund (National Museum, Copenhagen) Typeset with Linux Libertine by Marco Bianchi University of Oslo Uppsala University ISSN 1892-0950 Bracteates and Runes Review article by Nancy L. Wicker and Henrik Williams Die Goldbrakteaten der Völkerwanderungszeit — Auswertung und Neufunde. Eds. Wilhelm Heizmann and Morten Axboe. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 40. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2011. 1024 pp., 102 plates. ISBN 978-3-11-022411-5, e-ISBN 978-3-11-022411-2, ISSN 1866-7678. 199.95 €, $280. From the Migration Period we now have more than a thousand stamped gold pendants known as bracteates. They have fascinated scholars since the late seventeenth century and continue to do so today. Although bracteates are fundamental sources for the art history of the period, and important archae- o logical artifacts, for runologists their inscriptions have played a minor role in comparison with other older-futhark texts. It is to be hoped that this will now change, however. -

The Rise and Fall of Anglo-Saxon Runic Stone Monuments Runic Inscriptions and the Development of Sculpture in Early Medieval England

Runrön Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet 24 Kopár, Lilla, 2021: The Rise and Fall of Anglo-Saxon Runic Stone Monu- ments. Runic Inscriptions and the Development of Sculpture in Early Medi- eval England. In: Reading Runes. Proceedings of the Eighth International Sym posium on Runes and Runic Inscriptions, Nyköping, Sweden, 2–6 September 2014. Ed. by MacLeod, Mindy, Marco Bianchi and Henrik Williams. Uppsala. (Run rön 24.) Pp. 143–156. DOI: 10.33063/diva-438873 © 2021 Lilla Kopár (CC BY) LILLA KOPÁR The Rise and Fall of Anglo-Saxon Runic Stone Monuments Runic Inscriptions and the Development of Sculpture in Early Medieval England Abstract The Old English runic corpus contains at least thirty-seven inscriptions carved in stone, which are concentrated geographically in the north of England and dated mainly from the seventh to the ninth centuries. The quality and content of the inscriptions vary from simple names (or frag- ments thereof) to poetic vernacular memorial formulae. Nearly all of the inscriptions appear on monumental sculpture in an ecclesiastical context and are considered to have served commemor- ative purposes. Rune-inscribed stones show great variety in terms of monument type, from name-stones, cross-shafts and slabs to elaborate monumental crosses that served different func- tions and audiences. Their inscriptions have often been analyzed by runologists and epigraphers from a linguistic or epigraphic point of view, but the relationship of these inscribed monuments to other sculptured stones has received less attention in runological circles. Thus the present article explores the place and development of rune-inscribed monuments in the context of sculp- tural production in pre-Conquest England, and identifies periods of innovation and change in the creation and function of runic monuments. -

Context Analysis and Bracteate Inscriptions in Light of Alternative Iconographic Interpretations

Context analysis and bracteate inscriptions in light of alternative iconographic interpretations Nancy L. Wicker Although nearly 1000 Scandinavian Migration Period (fifth- and sixth-century) gold pendants called bracteates have been discovered in Scandinavia and throughout northern and central Europe, only about twenty percent of these objects have inscriptions. The writing is mostly in the elder futhark but also in corrupted Latin copied from inscriptions on Late Roman coins and medallions, which are presumably the models for bracteate imagery. Relatively few of the 170 bracteates with runic inscriptions—which are known from only 110 different dies (Düwel 2008: 46)—are semantically meaningful. While the research of the late Karl Hauck has dominated bracteate scholarship for the past forty years, his theory of bracteate iconography is not the only possible interpretation of this imagery that may illuminate our understanding of the inscriptions. In this paper, I will high- light other interpretations of bracteates, not as definitive answers to the meaning of bracteates but instead to emphasize the tenuous nature of all such theories. I also propose the use of what Michaela Helmbrecht (2008) has termed ‗context analysis‘ to focus on the various contexts in which bracteates have been discovered in order to shed additional light upon their meaning. Before presenting alternate explanations, I will review basic information about bracteates and their inscriptions, and I will summarize the basic tenets of Hauck‘s thesis. Bracteate classification and iconography From the earliest research on bracteates, scholars including C. J. Thomsen (1855), Oscar Montelius (1869), and Bernhard Salin (1895) focused on organizing these artifacts by classi- fying them into types according to details of images depicted in the central stamped field of decoration. -

MUFI Character Recommendation V. 3.0: Alphabetical Order

MUFI character recommendation Characters in the official Unicode Standard and in the Private Use Area for Medieval texts written in the Latin alphabet ⁋ ※ ð ƿ ᵹ ᴆ ※ ¶ ※ Part 1: Alphabetical order ※ Version 3.0 (5 July 2009) ※ Compliant with the Unicode Standard version 5.1 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ※ Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (MUFI) ※ www.mufi.info ISBN 978-82-8088-402-2 ※ Characters on shaded background belong to the Private Use Area. Please read the introduction p. 11 carefully before using any of these characters. MUFI character recommendation ※ Part 1: alphabetical order version 3.0 p. 2 / 165 Editor Odd Einar Haugen, University of Bergen, Norway. Background Version 1.0 of the MUFI recommendation was published electronically and in hard copy on 8 December 2003. It was the result of an almost two-year-long electronic discussion within the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (http://www.mufi.info), which was established in July 2001 at the International Medi- eval Congress in Leeds. Version 1.0 contained a total of 828 characters, of which 473 characters were selected from various charts in the official part of the Unicode Standard and 355 were located in the Private Use Area. Version 1.0 of the recommendation is compliant with the Unicode Standard version 4.0. Version 2.0 is a major update, published electronically on 22 December 2006. It contains a few corrections of misprints in version 1.0 and 516 additional char- acters (of which 123 are from charts in the official part of the Unicode Standard and 393 are additions to the Private Use Area). -

Myths of the Rune Stone: Viking Martyrs and the Birthplace of America

book review Myths of the Rune Stone: Viking Martyrs For example, Krueger’s and the Birthplace of America take on the local and reli- David M. Krueger gious dimensions of the (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015, 214 p., stone’s history is original. Paper, $24.95.) He excellently explores how the stone became a near- Many places claim to be the birthplace of America, but few sacred artifact even outside have been as contested as the one near Kensington, Minnesota. the Scandinavian American The source of this claim, a stone slab unearthed in 1898, is the ethnic community. Krueger subject of David Krueger’s Myths of the Rune Stone. This first shows how in the 1920s the comprehensive book about the popular meaning of the Kens- stone— by way of a failed ington Rune Stone is a welcome contribution to the study of its plan for a massive 200- foot historiography and to the impact of local culture on an Ameri- monument— became a can origin myth. tool of small- town booster- Since its discovery by a Swedish- born farmer, the Kensing- ism. In 1928, the stone was ton Rune Stone’s claim that Norsemen were present in what purchased by a group of is now Minnesota in the year 1362 has been a topic of heated Alexandria businessmen controversy. Although scholars of Scandinavian languages and and put on display in a downtown bank. To the Alexandria runology (the study of runic inscriptions) have long agreed community, the stone was a source of prestige and a strategy about its nineteenth- century origin, the stone has continued to to promote tourism. -

Anglo-Saxon Runes

Runes Each rune can mean something in divination (fortune telling) but they also act as a phonetic alphabet. This means that they can sound out words. When writing your name or whatever in runes, don’t pay attention to the letters we use, but rather the sounds we use to make up the words. Then finds the runes with the closest sounds and put them together. Anglo- Swedo- Roman Germanic Danish Saxon Norwegian A ansuz ac ar or god oak-tree (?) AE aesch ash-tree A/O or B berkanan bercon or birch-twig (?) C cen torch D dagaz day E ehwaz horse EA ear earth, grave(?) F fehu feoh fe fe money, cattle, money, money, money, wealth property property property gyfu / G gebo geofu gift gift (?) G gar spear H hagalaz hail hagol (?) I isa is iss ice ice ice Ï The sound of this character was something ihwaz / close to, but not exactly eihwaz like I or IE. yew-tree J jera year, fruitful part of the year K kenaz calc torch, flame (?) (?) K name unknown L laguz / laukaz water / fertility M mannaz man N naudiz need, necessity, nou (?) extremity ing NG ingwaz the god the god "Ing" "Ing" O othala- hereditary land, oethil possession OE P perth-(?) peorth meaning unclear (?) R raidho reth (?) riding, carriage S sowilo sun or sol (?) or sun tiwaz / teiwaz T the god Tiw (whose name survives in Tyr "Tuesday") TH thurisaz thorn thurs giant, monster (?) thorn giant, monster U uruz ur wild ox (?) wild ox W wunjo joy X Y yr bow (?) Z agiz(?) meaning unclear Now write your name: _________________________________________________________________ Rune table borrowed from: www.cratchit.org/dleigh/alpha/runes/runes.htm . -

Signs and Symbols Represented in Germanic, Particularly Early Scandinavian, Iconography Between the Migration Period and the End of the Viking Age

Signs and symbols represented in Germanic, particularly early Scandinavian, iconography between the Migration Period and the end of the Viking Age Peter R. Hupfauf Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Sydney, 2003 Preface After the Middle Ages, artists in European cultures concentrated predominantly on real- istic interpretations of events and issues and on documentation of the world. From the Renaissance onwards, artists developed techniques of illusion (e.g. perspective) and high levels of sophistication to embed messages within decorative elaborations. This develop- ment reached its peak in nineteenth century Classicism and Realism. A Fine Art interest in ‘Nordic Antiquity’, which emerged during the Romantic movement, was usually expressed in a Renaissance manner, representing heroic attitudes by copying Classical Antiquity. A group of nineteenth-century artists, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Holman Hunt and Everett Millais founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. John Ruskin, who taught aesthetic theory at Oxford, became an associate and public defender of the group. The members of this group appreciated the symbolism and iconography of the Gothic period. Rossetti worked together with Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris. Morris was a great admirer of early Scandinavian cultures, and his ideas were extremely influential for the development of the English Craft Movement, which originated from Pre-Raphaelite ideology. Abstraction, which developed during the early twentieth century, attempted to communicate more directly with emotion rather then with the intellect. Many of the early abstract artists (Picasso is probably the best known) found inspiration in tribal artefacts. However, according to Rubin (1984), some nineteenth-century primitivist painters appreciated pre-Renaissance European styles for their simplicity and sincerity – they saw value in the absence of complex devices of illusio-nist lighting and perspective. -

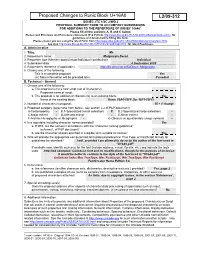

Proposed Additions Red = Proposed Changes Green = Other Possible Additions Black = Existing/Unchanged

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Ms 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: 4 September 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/fa/Deron_Malgorzata 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: If needed B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): - Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic 16A0-16FF (for 16F1-16FF) 2. Number of characters in proposal: 15 + 1 change 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary - B.1-Specialized (small collection) X B.2-Specialized (large collection) - C-Major extinct - D-Attested extinct - E-Minor extinct - F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic - G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols - 4. -

Proměny Futharku V Souvislosti S Vývojem Runové Švédštiny

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav jazykovědy a baltistiky Obecná jazykověda Pavlína Lukešová Proměny futharku v souvislosti s vývojem runové švédštiny Bakalářská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: prof. RNDr. Václav Blaţek, CSc. 2015 Prohlášení Tímto prohlašuji, ţe jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně a pouţila v ní pouze uvedenou literaturu. V Brně dne 30.6.2015 ……………………………………….. Poděkování Chtěla bych poděkovat prof. RNDr. Václavu Blaţkovi, CSc. za odborné vedení bakalářské práce a cenné rady, které mi pomohly tuto práci zkompletovat. Také bych zde chtěla poděkovat Mgr. Alarce Kempe za podporu při studiu staroseverštiny. ABSTRAKT Tato bakalářská práce je zaměřena na zpracování hláskových změn při vývoji runové švédštiny ve vztahu k písmu jednotlivých vývojových fází jazyka. Hlavním záměrem práce je tedy vyselektovat dané změny z dostupného jazykového materiálu a pokusit se je doloţit v konkrétních textech vybraných runových nápisů. Kromě přehledu vývoje jazyka a runového písma práce zahrnuje i vysvětlení procesů potřebných pro získání jazykového materiálu z runových nápisů. Klíčová slova: futhark, runy, švédština, staroseverština, jazykové změny SUMMARY This bachelor thesis focuses on processing of sound changes accompanying the development of runic Swedish in relation to writing system of various developmental stages of the language. The main aim of this paper is to select such changes from available language material and to demonstrate them in chosen texts of runic inscriptions. This thesis also includes an explanation of the processes necessary for obtaining the language material from the runic inscriptions. Key words: futhark, runes, swedish, old norse, language changes 1. ÚVOD ...................................................................................................................5 2. POPIS PRAMENŮ...............................................................................................7 1.1. Transliterace a normalizace runových nápisů.........................................7 1.2. -

The Elder Futhark Rune Poem Final Draft

The Elder Futhark Rune Poem Final Draft The Elder Futhark The oldest rune row From the roots of the world tree, Yggdrasil, Connecting humanity, To the divine. The runes of Odin, 24 in total. Gathered from the roots of the World Tree, Through a trial by ordeal Of nine days and nine nights Hanging from an branch of Yggdrasil, Wounded by his own spear. Hearing their songs, Seeing their shapes He took them back with him Screaming their songs. The Elder Futhark, A guide to life A guide to making magick in time with the cosmic order. Freyja's Aett The aett of magick and initiation, Maintaining magickal order To Hagal's Aett The guide to the difficulties in your life, How to learn and grow from them And how to overcome them. Then to Tyr's Aett, Order and organisation Of Midguard and the worlds beyond. As above, So below. Elder Fultark Rune Poem - Khel'Shen Kyshera Du'Skhall Kre'mashen Akh'Hense 1 We first introduce Freyja's Aett, The aett of magick The aett of power The aett giving us the tools to master our fate. From Fehu, Symbolising abundance, energy and manifestation. The rune of material wealth. To Uruz, Signifying unbound universal will, The rune of the Aurochs, The rune of the primal cow, Audhuamla. To Thurisaz, The mighty protective rune The rune of protection and endurance, Of overcoming our challenges. To Anzus, The rune of the World Tree, Yggdrasil, Standing tall over all. To Raidho, The rune of the journey, Physical or mental, Mundane or spiritual.