Reconstructing the Alexander Nevsky Film Score

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

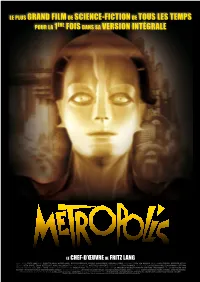

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

5. September 2020 Vladimir Jurowski 2 BEETHOVEN – SINFONIE NR

5. September 2020 Vladimir Jurowski 2 BEETHOVEN – SINFONIE NR. 7 „Der Stil also, den Schönberg und seine Schule sucht, ist eine neue Durchdringung des musika- lischen Materials in der Horizontalen und in der Vertikalen, eine Polyphonie, die ihre Höhepunkte bisher gefunden hat bei den Niederländern und bei Bach, und dann weiter bei den Klassikern.“ Anton Webern 4 PROGRAMM 5 Johann Sebastian Bach Anton Webern (1685 – 1750) (1883 – 1945) Fuga (2. Ricercata) à 6 voci aus Variationen für Orchester op. 30 5. September 2020 „Ein musikalisches Opfer“ BWV 1079, für Orchester gesetzt Alfred Schnittke Samstag /19 Uhr von Anton Webern (1934 – 1998) Philharmonie Berlin Concerto grosso Nr. 1 für zwei Alban Berg Violinen, Cembalo, präpariertes (1885 – 1935) Klavier und Streichorchester Drei Bruchstücke für Gesang und › Preludio. Andante Orchester aus der Oper „Wozzeck“ › Toccata. Allegro op. 7 nach Georg Büchners › Recitativo. Lento Drama – für den Konzertgebrauch › Cadenza VLADIMIR JUROWSKI eingerichtet von Alban Berg, Be- › Rondo. Agitato – Meno mosso – Anne Schwanewilms / Sopran arbeitung für kleines Orchester Tempo I Erez Ofer / Violine von Eberhard Kloke › Postludio. Andante – Allegro – Nadine Contini / Violine › Langsam (I. Akt, Szenen 2, 3) Andante Helen Collyer / Klavier und Cembalo › Thema, sieben Variationen und Kinderchor der Staatsoper Unter den Linden Berlin Fuge (III. Akt, Szene 1) Vinzenz Weissenburger / Choreinstudierung › Langsam (III. Akt, Szenen 4, 5) Ralf Sochaczewsky / Assistent des Chefdirigenten Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin Liebe Konzertbesucher*innen! Schön, dass Sie da sind! Lassen Sie uns gemeinsam dafür sorgen, dass das nicht nur so bleiben, sondern bald wieder zur erfreulichen Normalität werden kann! Bitte beachten Sie die allgemeine Hygiene-, Husten- und Nies-Etikette, folgen Sie der besonderen Wegführung innerhalb des Hauses und halten Sie den Mindestabstand von 1,5 Metern ein. -

Metropolismetropolis

METROPOLISMETROPOLIS Stummfilm 1927 Regie: Fritz Lang Drehbuch: Fritz Lang, Thea von Harbou Original-Musik: Gottfried Huppertz Produzent: Erich Pommer Kaum ein anderer deutscher Film hat die Geschichte des Films nachhaltiger beeinflusst, als der Stummfilmklassiker METROPOLIS von 1927. Mit für damalige Zeit enormem Aufwand in den Babelsberger UFA-Studios gedreht, fanden Bildsprache und Motive des Regisseurs Fritz Lang Anklang und Adaption in zahlreichen späteren Filmen vor allem amerikanischer Regisseure. Visionär wird eine Welt gezeigt, in Originalmusik seit Jahren immer wieder der gigantischer Reichtum und Macht einerseits konzertante Aufführung in den verschiedensten und eine menschenfeindliche Maschinenwelt Besetzungen. andererseits zu Konflikt und Katastrophe führen. Im November 2001 wurde der Film Metropolis ist eine zweigeteilte Stadt. In den METROPOLIS (neben Goethes Faust, der Hochhäusern residieren die Reichen und Gutenberg-Bibel und Beethovens 9. Sinfonie in Mächtigen - Vorstellungen vom biblischen das UNESCO-Weltkulturerbe aufgenommen. Turmbau zu Babel werden hier ins Bild gesetzt. Tief unter der Erde leben die Arbeiter. Sie Gr. Orch.: (Filmfassg. 2001 Bearb.: Heller) werden vom Moloch einer alles beherrschenden 2 (Picc.). 2 (EH.). 2. 2. 2 Alt-Sax.-4. 2. 3. 1. Maschine angetrieben und in Schach gehalten. Pk. Schlgz. (3 Sp.) Harfe, Celesta, Orgel, Str. Maria, einem Mädchen aus der Unterstadt, das (Part. auch käufl. Best.-Nr. 51150, Euro 149,--) die Arbeiter verehren wie eine Heilige, wird (Filmfassg. 2010 Bearb.: Strobel - gleiche Bes.) von Freder, dem Sohn des obersten Magnaten bewundert und geliebt. Ein künstlicher Mensch SO.-Fassung: (2001 Heller, 2010 Strobel) mit dem Aussehen der Maria, ins Leben gesetzt 1 (Picc.). 1 (EH.) 1. 0. Alt-Sax.-2. 1. 1. -

Bertelsmann Sponsors Restoration of a Fritz Lang Classic

PRESS RELEASE Bertelsmann Sponsors Restoration of a Fritz Lang Classic Legendary silent movie “Destiny” (Der müde Tod) is restored to historical color-tinting as part of digital restoration Another show of support for preserving German film legacy Worldwide premiere at the 2016 Berlinale Berlin, December 2, 2015 – The international media company Bertelsmann is sponsoring the restoration of an early masterpiece by “Metropolis” director Fritz Lang and is thus renewing its commitment to preserving German film legacy. The Group is the main sponsor of the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation’s comprehensive digital restoration of the 1921 silent movie “Destiny.” No theater copies of the legendary production from UFA’s historical legacy survived from the time. Copies produced later lack the coloration that once characterized this Weimar cinema classic, which is now being restored modeled on other works of the time. The Murnau Foundation and its partners have been working on the project since fall 2014, using materials and resources from the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Munich Film Museum and the Národní filmový archiv in Prague, among others. On February 12, 2016, "Destiny" will return to the big screen with its historical color-tinting intact at the International Film Festival in Berlin. The digital version will be shown as part of the “Berlinale Classics.” A new film score, produced by ZDF/ARTE, is being created for this world premiere and for subsequent use on TV, at movie theaters, on DVD and Blu-ray. Silent movie specialist Frank Strobel will conduct the famous Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra (RSB). The presentation of “Destiny” at the “Berlinale Classics” is a collaboration between the Berlin International Film Festival, Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen, the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation, ZDF/ARTE, and the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra. -

DAS MAGAZIN 06 JAN / FEB 2011 Gustavo Dudamel Und Das Los Angeles Phiharmonic „Metropolis“ Im Original Und Klassiker Von

DAS MAGAZIN 06 JAN / FEB 2011 Gustavo Dudamel und das Los Angeles Phiharmonic Zwei Konzerte mit Werken von Gustav Mahler, Leonard Bernstein und anderen Semyon Bychkov am Pult der Wiener Philharmoniker Erstmals dirigiert er in Köln Gustav Mahlers Sinfonie Nr. 6 „Metropolis“ im Original und Klassiker von Fellini Große Orchester spielen live, dirigiert von Frank Strobel, zu großen Film-Higlights Gustavo Dudamel EDITORIAL BB Promotion GmbH in association with UAU International presents BESONDERE Ausgabe 06/2010: Januar / Februar 2011 HÖREMPFEHLUNGEN VON SONY CLASSICAL Liebe Besucherinnen und Besucher, SIMONE KERMES liebe Freundinnen und Freunde der Kölner Philharmonie, COLORI D’AMORE µOWLPR7DQJR das Ende des Jahres mit seinen besinnlichen Weihnachtsfeiertagen „Das ist eine in samten- und dem Jahreswechsel ist auch immer eine Zeit, in der man Vergan- goldenes Abendrot genes Revue passieren lässt, um sich auf Neues einstellen zu können. getauchte mystische Seelenlandschaft. 02. - 03.01.11 · Kölner Philharmonie Und spätestens beim letzten Sekt des Silvesterabends ist die Zeit für Gesungene Utopie – gute Vorsätze gekommen. und doch ganz real! TICKETS: 0221 - 280 280 Wundervoll!“ BR-Online Wir von der KölnMusik haben schon lange vor diesem letzten Silvester- MICHAEL BRENNER FOR BB PROMOTION GMBH PRESENTS Sekt einen guten Vorsatz gefasst: Das Jahr 2011 in der Kölner Phil- 88697723192 88697723192 Die neue CD der „Queen of Baroque“ (Opera News) harmonie soll das Jahr der vielen musikalischen Neuentdeckungen mit italienischen Barock-Arien von Scarlatti, Bononcini, werden. Und gleich die ersten Monate des Jahres bieten derlei viele Caldara, Matteis & Broschi. 13 davon sind Weltersteinspielungen. Entdeckungen: Am Neujahrstag wird der faszinierende Jung-Organist www.simone-kermes.de Cameron Carpenter ein Konzert geben, der mit seinem Spiel gerade- zu eine Revolutionierung der Orgelmusik und des Organistentums ermöglicht hat. -

Programmheft Zum Konzert Sounds of Cinema 2014

Donnerstag, 26. Juni 2014 Circus-Krone-Bau 20.00 Uhr – Ende ca. 22.45 Uhr Sounds of Cinema »MAGIC!« MARJUKKA TEPPONEN Sopran GÖTZ ALSMANN Moderation CHOR DES BAYERISCHEN RUNDFUNKS MÜNCHNER RUNDFUNKORCHESTER ULF SCHIRMER Leitung MATTHIAS KELLER Programmgestaltung und Dramaturgie GUSTAF SJÖKVIST Choreinstudierung AUSZUBILDENDE MEDIENGESTALTER/-INNEN BILD UND TON / DIGITAL UND PRINT DUALES STUDIUM MEDIENDESIGN (Projektleitung: Beatrix Rottmann / Erich Höpfl) Projektionen Video-Livestream über www.br-klassik.de Das Konzert kann anschließend ein halbes Jahr lang im Internet abgerufen werden. Direktübertragung des Konzerts im Hörfunk auf BR-KLASSIK in Surround. In der Pause: PausenZeichen. »Zwischen Shakespeare und Disney-Cartoon.« Matthias Keller im Gespräch mit Patrick Doyle (als Podcast verfügbar) Übertragung im Bayerischen Fernsehen: So., 29. Juni 2014, um 22.00 Uhr PROGRAMM ALFRED NEWMAN (1901–1970) »20th Century Fox Fanfare« Arr.: Matthias Keller JOHN WILLIAMS (* 1932) »Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone« Harry’s Wondrous World Film: 2001; Regie: Chris Columbus DANNY ELFMAN (* 1953) »Alice in Wonderland« Alice’s Theme Arr.: Steve Bartek Film: 2010; Regie: Tim Burton Frauenchor des Chores des Bayerischen Rundfunks ROBERT B. SHERMAN (1925–2012) RICHARD M. SHERMAN (* 1928) TERRY GILKYSON (1916–1999) »The Jungle Book« Medley Arr.: Ken Whitcomb Film: 1967; Regie: Wolfgang Reitherman MOON YUNG OH Tenor ANDREW LEPRI MEYER Tenor CHRISTOF HARTKOPF Bariton WOLFGANG KLOSE Bass Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks HAROLD ARLEN (1905–1986) »The Wizard -

Frank Strobel's Biography

FRANK STROBEL CONDUCTOR Cine-concert specialist, the German conductor Frank Strobel is a renowned arranger, editor and producer. He spent his childhood in Munich in the cinema run by his parents. In 2004, he reconstituted and edited the score composed by Prokofiev for the film Alexandre Nevski (Sergej Eisenstein). He presented this new version at the Konzerthaus in Berlin with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and then at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. On the occasion of the projection of Der Rosenkavalier (Robert Wiene) at the Dresden Opera in 2006, he conducted the Dresden Staatskapelle and played Richard Strauss’s reconstituted score. Following the discovery in 2008 of an original copy of Metropolis by Fritz Lang in Buenos Aires, he conducted the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and played the music of Gottfried Huppertz for the first projection of the restored version of the film at the 2010 Bienale. The following year, he conducted the Philharmonic Orchestra of the NDR of Hanover for the projection of Matrix (music by Don Davis) at the Royal Albert Hall in London. In 2014, with the Orchestre philharmonique de Radio France he gave the first performance of the music composed by Philippe Schoeller for the film J’accuse directed by Abel Gance in 1919. In 2016, he reconstituted the score of the music to Ivan the Terrible (Sergej Eisenstein), given for the first time in the complete version and in Prokofiev’s original orchestration at the Berlin Musikfest with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra. On top of cine-concerts, he is a specialist of the late romantic composers such as Schreker, Zemlinsky and Siegfried Wagner, whose works he has taken up again and reproduced. -

Friday Series 3 Alexander Nevsky

13.10. FRIDAY SERIES 3 Helsinki Music Centre at 19.00 ALEXANDER NEVSKY (Soviet Union 1938) Frank Strobel, conductor Anna Danik, mezzo-soprano Helsinki Music Centre Choir, coach Nils Schweckendiek Production company: Mosfilm Directed by. Sergei Eisenstein, Dmitri Vasilyev Assisted by: Boris Ivanov, Nikolai Maslov Written by: Sergei Eisenstein, Pyotr Pavlenko Cinematography: Eduard Tissé Production design: Iosif Shpinel, Nikolai Solovyov, Konstan- tin Eliseev – after the sketches by Eisenstein Music: Sergei Prokofiev Lyricist: Vladimir Lugovskoi Sound: Vladimir Bogdankevich Editing: Sergei Eisenstein Editing assistant: Esfir Tobak Historical consultant: A. V. Artsihovsky Military consultant: K. G. Kalmykov CAST: Nikolai Cherkasov (Prince Alexander Nevsky), Nikolai Okhlopkov (Vasili Buslaev), Andrei Abrikosov (Gavrilo Oleksich), Dmitri Orlov (Ignat, master armourer), Vasili Novikov (Pavsha, Governor of Pskov), Nikolai Arsky (Domash Tverdislavich, a Novgorod boyar), Varvara Massalitinova (Amelfa Timoferevna, Buslai’s mother), Valentina Ivashova (Olga Danilovna, a maid of Novgorod), Aleksandra Danilova (Vasilisa, a maid of Pskov), Vladimir Yershov (Hermann von Balk, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order), Sergei Blinnikov (Tverdilo, the traitor of Pskov), Ivan Lagutin (Anani, a monk), Lev Fenin (the Archbishop), Naum Rogozhin (the Black-Hooded Monk) 1 Premiere: 23.11.1938 Moscow FILMPHILHARMONIC EDITION Film by courtesy of the EUROPEAN FILMPHILHARMONIC INSTITUTE / Mosfilm, Music by courtesy of Sikorski Musikverlage. There will be no interval. The concert will end at about 20:55. 2 THE FILM knights attack with geometrical pre- cision (in formations known as a “pig” and a “Macedonian phalanx”), while the After his death, Prince Alexander Russians swarm hither and thither in ir- of Novgorod, began to be called regular waves. The knights are accom- Alexander Nevsky, meaning “of Neva”. -

METROPOLIS 27/10 – Timp.Perc – Pno.Hrm – Strings 145 Min

Source: Boris Streubel Source: It all started in Buenos Aires in 2008. The METROPOLIS restoration project, which attracted Director: Fritz Lang international attention, began with the surprise discovery of a long-forgotten unique version (GER, 1927) of the film, including scenes that were previously believed lost. It is these new parts that sets Music: Gottfried Huppertz; METROPOLIS apart from the earlier, substantially shorter 1988 and 2001 versions. Against the adaptation and synchroniza- breath-taking science fiction background, the human element has been given a more promi- tion: Frank Strobel; reinstru- nent role, adding a different slant to the storyline. mentation of missing parts: Marco Jovic (2010) The music plays a crucial role in the reconstructed montage of the premiere version, the pri- Adaptation for two pianos: mary source being the original score by Gottfried Huppertz. Felix Treiber (2011) Political and economic power in Metropolis centres on one person: From the ‘New Tower of Babel’, Joh Fredersen reigns like an absolute monarch over Upper Town and Lower Town. Per- Instrumentation ceiving himself as the ‘brain’, the ruler considers people as mere ‘hands’ in the machinery. The (large orchestra): human aspect - love and friendship, rebellion and revenge - is still powerful enough to shake 1+1/pic.1+1/ca.2+2asax.2 – the foundations of the futuristic city’s technological world. 4.3.3.1 – timp.3perc – cel.org – hp – strings Instrumentation (small orchestra): 1/pic.1/ca.1+asax.0 – 2.1.1.0 METROPOLIS 27/10 – timp.perc – pno.hrm – strings 145 min. The rich and powerful reside in Upper Town. -

Literature Film Music Art History

Literature Film Music Art History Culture@Bertelsmann Culture@Bertelsmann 3 Bertelsmann is a media, services and education company that Dear Readers, operates in about 50 countries around the world. It includes Dear Friends of Bertelsmann, the broadcaster RTL Group, the trade book publisher Penguin Random House, the magazine publisher Gruner + Jahr, the music For over 180 years, Bertelsmann has offered authors and artists company BMG, the service provider Arvato, the Bertelsmann the opportunity to produce creative content and make it accessible Printing Group, the Bertelsmann Education Group and to a broad audience. This creativity entertains and inspires Bertelsmann Investments, an international network of funds. millions of people around the world, every day. For this reason, The company has 119,000 employees and generated revenues Bertelsmann works with creatives to promote numerous cultural of €17.2 billion in the 2017 financial year. Bertelsmann stands projects in the fields of literature, film, music and the arts. for entrepreneurship and creativity. This combination promotes first-class media content and innovative service solutions that The preservation and protection of creative works has always inspire customers around the world. been part of our own company history. So Bertelsmann supports, at various levels, historical and cultural projects that support this cause. Culture@Bertelsmann is closely linked to Bertelsmann‘s tradition and creative products, because creativity is an engine for diversity and innovation – in the company, as well as in society. Yours sincerely, Thomas Rabe Culture@Bertelsmann 5 Contents Literature 6 Film 14 Music 22 Art & Culture 30 Company History 38 Culture@Bertelsmann Literature Books are part of Bertelsmann‘s DNA – they are inextricably bound up with the company. -

Fritz Lang's Destiny

FRITZ LANG’S DESTINY (DER MÜDE TOD) Official Selection, 2016 Berlinale Film Festival 1921 / Germany / 98 min. / Color Tinted / Not Rated Digitally restored 2016 version in 2K DCP Press materials: www.kinolorber.com Distributor Contact: Kino Lorber 333 W. 39th Street New York, NY 10018 Rodrigo Brandao, [email protected] Matt Barry, [email protected] Short Synopsis: A young woman (Lil Dagover) confronts the personification of Death (Bernhard Goetzke), in an effort to save the life of her fiancé (Walter Janssen). Death weaves three romantic tragedies and offers to unite the girl with her lover, if she can prevent the death of the lovers in at least one of the episodes. Thus begin three exotic scenarios of ill-fated love, in which the woman must somehow reverse the course of destiny: Persia, Quattrocento Venice, and a fancifully rendered ancient China. Long Synopsis: A cloaked figure (Bernhard Goetzke) materializes on the side of a country road and boards a carriage occupied by a pair of young lovers (Lil Dagover, Walter Janssen). A flashback reveals that this mysterious figure had obtained a plot of property adjoining the local cemetery—a plot of land surrounded by high walls—walls without window or gate—at which he stands as a sentinel. After arriving at a quaint village, the lovers drink a traditional toast to their relationship, but the specter of death emerges (a drinking glass transforms into an hourglass, alongside which is the shadow of the stranger’s walking stick, capped by the figure of a skeleton). Soon thereafter, the young woman learns that her fiancé has been taken away by the stranger, who is now quite apparently the personification of death. -

Download Detailseite

Berlinale 2010 Fritz Lang Berlinale Special METROPOLIS Gala METROPOLIS METROPOLIS Deutschland 1927/2010 Darsteller Maria/ Länge 147 Min. Maschinenmensch Brigitte Helm Format HDCAM-SR Johann Schwarzweiß „Joh“ Fredersen Alfred Abel Restaurierte Fassung Freder Fredersen Gustav Fröhlich Erfinder Rotwang Rudolf Klein- Stabliste Rogge Regie Fritz Lang Der Schmale Fritz Rasp Buch Thea von Harbou, Josaphat/Joseph Theodor Loos nach ihrem Roman Nr. 11811 Erwin Biswanger Kamera Karl Freund Grot, Wärter der Günther Rittau Herzmaschine Heinrich George Kamera-Assistenz Robert Baberske Jan Olaf Storm Günther Anders Marinus Hanns Leo Reich H. O. Schulze Zeremonienmeister Heinrich Gotho Optische Spezial- Dame im Auto Margarete Lanner effekte Eugen Schüfftan Arbeiter Max Dietze Ernst Kunstmann Georg John Trick-Kamera Helmar Lerski Walter Kurt Kühle Arthur Reinhardt Konstantin Tschet Skizze: Christina Kim Schnitt Fritz Lang Erwin Vater Bauten Otto Hunte Arbeiterinnen Grete Berger Erich Kettelhut METROPOLIS Olly Boeheim Karl Vollbrecht Fritz Langs METROPOLIS kehrt nahezu in der Originalfassung auf die Kino - Ellen Frey Plastiken Walter Schulze- leinwand zurück! 83 Jahre nach der Uraufführung wird die von der Fried - Lisa Gray Mittendorff rich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung restaurierte Fassung des Stummfilm klassi - Rosa Liechtenstein Helene Weigel Kostüm Änne Willkomm kers bei der Berlinale – und vor dem Brandenburger Tor – ihre Premiere fei- Musik Gottfried Huppertz Frauen der (Kinomusik 1927) ern. Nach der Originalpartitur von Gottfried Huppertz wird die Aufführung ewigen Gärten Beatrice Garga Produzent Erich Pommer vom Rundfunk-Sinfonie orchester Berlin unter der Leitung von Dirigent Annie Hintze Produktion Universum-Film Frank Strobel begleitet. Margarete Lanner AG (Ufa), Berlin Die Verstümmelung des Monumentalfilmes hatte unmittelbar nach seiner Helen von Münchhofen Drehzeit 22.5.1925– Premiere am 10.