Sergei Eisenstein's 26 October 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

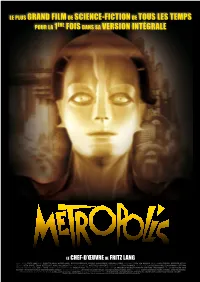

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

An Introduction to Jere Abbott's Russian Diary, 1927–1928*

An Introduction to Jere Abbott’s Russian Diary, 1927 –1928* LEAH DICKERMAN In 1978, in its seventh issue, October published the travel diaries written by Alfred H. Barr, Jr., who would go on to become the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, during his two-month sojourn in Russia in 1927–28. They were accompanied by a note from Barr’s wife, Margaret Scolari Barr, who had made the documents available, and an introduction written by Jere Abbott, an art historian and former director of the Smith College Museum of Art who had returned to his family’s textile business in Maine. Abbott and Barr had made the journey together, traveling from London in October 1927 to Holland and Germany (including a four-day visit to the Bauhaus) and then, on Christmas Day 1927, over the border into Soviet Russia. Abbott, as Margaret Barr had noted, kept his own journal on the trip. Abbott’s, if anything, was more detailed and expansive in documenting its author’s observations and perceptions of Soviet cultural life at this pivotal moment; and his perspective offers both a complement and counter - point to Barr’s. Russia after the revolution was largely uncharted territory for Anglophone cultural commentary: This, in combination with the two men’s deep interest in and knowledge of contemporary art, makes their journals rare docu - ments of the Soviet cultural terrain in the late 1920s. We present Abbott’s diaries here, thirty-five years after the publication of Barr’s, with thanks to the generous cooperation of the Smith College Museum of Art, where they are now held. -

Consumerism in the 1920S: Collected Commentary

BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION ONTEMPORAR Y HE WENTIES IN OMMENTARY T T C * Leonard Dove, The New Yorker, October 26, 1929 — CONSUMERISM — Mass-produced consumer goods like automobiles and ready-to-wear clothes were not new to the 1920s, nor were advertising or mail- order catalogues. But something was new about Americans’ relationship with manufactured products, and it was accelerating faster than it could be defined. Not only did the latest goods become necessities, consumption itself became a necessity, it seemed to observers. Was that good for America? Yes, said some—people can live in unprecedented comfort and material security. Not so fast, said others—can we predict where consumerism is taking us before we’re inextricably there? Something new has come to confront American democracy. Samuel Strauss The Fathers of the Nation did not foresee it. History had opened “Things Are in the Saddle” to their foresight most of the obstacles which might be expected The Atlantic Monthly to get in the way of the Republic—political corruption, extreme November 1924 wealth, foreign domination, faction, class rule; . That which has stolen across the path of American democracy and is already altering Americanism was not in their calculations. History gave them no hint of it. What is happening today is without precedent, at least so far as historical research has discovered. No reformer, no utopian, no physiocrat, no poet, no writer of fantastic romances saw in his dreams the particular development which is with us here and now. This is our proudest boast: “The American citizen has more comforts and conveniences than kings had two hundred years ago.” It is a fact, and this fact is the outward evidence of the new force which has crossed the path of American democracy. -

5. September 2020 Vladimir Jurowski 2 BEETHOVEN – SINFONIE NR

5. September 2020 Vladimir Jurowski 2 BEETHOVEN – SINFONIE NR. 7 „Der Stil also, den Schönberg und seine Schule sucht, ist eine neue Durchdringung des musika- lischen Materials in der Horizontalen und in der Vertikalen, eine Polyphonie, die ihre Höhepunkte bisher gefunden hat bei den Niederländern und bei Bach, und dann weiter bei den Klassikern.“ Anton Webern 4 PROGRAMM 5 Johann Sebastian Bach Anton Webern (1685 – 1750) (1883 – 1945) Fuga (2. Ricercata) à 6 voci aus Variationen für Orchester op. 30 5. September 2020 „Ein musikalisches Opfer“ BWV 1079, für Orchester gesetzt Alfred Schnittke Samstag /19 Uhr von Anton Webern (1934 – 1998) Philharmonie Berlin Concerto grosso Nr. 1 für zwei Alban Berg Violinen, Cembalo, präpariertes (1885 – 1935) Klavier und Streichorchester Drei Bruchstücke für Gesang und › Preludio. Andante Orchester aus der Oper „Wozzeck“ › Toccata. Allegro op. 7 nach Georg Büchners › Recitativo. Lento Drama – für den Konzertgebrauch › Cadenza VLADIMIR JUROWSKI eingerichtet von Alban Berg, Be- › Rondo. Agitato – Meno mosso – Anne Schwanewilms / Sopran arbeitung für kleines Orchester Tempo I Erez Ofer / Violine von Eberhard Kloke › Postludio. Andante – Allegro – Nadine Contini / Violine › Langsam (I. Akt, Szenen 2, 3) Andante Helen Collyer / Klavier und Cembalo › Thema, sieben Variationen und Kinderchor der Staatsoper Unter den Linden Berlin Fuge (III. Akt, Szene 1) Vinzenz Weissenburger / Choreinstudierung › Langsam (III. Akt, Szenen 4, 5) Ralf Sochaczewsky / Assistent des Chefdirigenten Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin Liebe Konzertbesucher*innen! Schön, dass Sie da sind! Lassen Sie uns gemeinsam dafür sorgen, dass das nicht nur so bleiben, sondern bald wieder zur erfreulichen Normalität werden kann! Bitte beachten Sie die allgemeine Hygiene-, Husten- und Nies-Etikette, folgen Sie der besonderen Wegführung innerhalb des Hauses und halten Sie den Mindestabstand von 1,5 Metern ein. -

Lonesome (1928)

Lonesome (1928) By Raquel Stecher they’re really neighbors. The audience “In the whirlpool of modern life -- The suspends their disbelief for the joyous most difficult thing is to live alone.” reunion of the two lovebirds who will never be lonesome again. For the film industry, 1928 was a turbulent year. A major transition was If it wasn’t for the insistence of Fejos, occurring; one that would forever alter Lonesome might never have been how movies were made. Just one year made. Much like the industry itself, prior, The Jazz Singer (1927), a part- Fejos was in a state of transition. Born talkie, a silent film with a few talking and raised in Hungary, he studied sequences added in, would make a medicine, became a medical orderly splash in Hollywood. Audiences flocked during WWI and then switched careers to the theatres and the once reluctant and worked on films in his native studio heads realized that the transition country. He moved to New York City in to sound was inevitable. Filmmakers the 1920s but struggled to make ends scrambled to learn the new technology meet. He then moved to Hollywood and develop movies to go with it. In determined to make his first feature film. 1929 all-talking films became the With some hard work, ingenuity and standard and once the industry was well some help, he produced The Last into the 1930s silent filmmaking was Moment (1927). The film was officially a thing of the past. The time successful and Universal Pictures came between 1927 and 1929 was pivotal and calling. -

Staging the Urban Soundscape in Fiction Film

Echoes of the city : staging the urban soundscape in fiction film Citation for published version (APA): Aalbers, J. F. W. (2013). Echoes of the city : staging the urban soundscape in fiction film. Maastricht University. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20131213ja Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2013 DOI: 10.26481/dis.20131213ja Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930)

The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930) FIONA FORD, MA Thesis submitted to The University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DECEMBER 2011 Abstract This thesis discusses the film scores of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930), composed in Berlin and London during the period 1926–1930. In the main, these scores were written for feature-length films, some for live performance with silent films and some recorded for post-synchronized sound films. The genesis and contemporaneous reception of each score is discussed within a broadly chronological framework. Meisel‘s scores are evaluated largely outside their normal left-wing proletarian and avant-garde backgrounds, drawing comparisons instead with narrative scoring techniques found in mainstream commercial practices in Hollywood during the early sound era. The narrative scoring techniques in Meisel‘s scores are demonstrated through analyses of his extant scores and soundtracks, in conjunction with a review of surviving documentation and modern reconstructions where available. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) for funding my research, including a trip to the Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt. The Department of Music at The University of Nottingham also generously agreed to fund a further trip to the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin, and purchased several books for the Denis Arnold Music Library on my behalf. The goodwill of librarians and archivists has been crucial to this project and I would like to thank the staff at the following institutions: The University of Nottingham (Hallward and Denis Arnold libraries); the Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt; the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin; the BFI Library and Special Collections; and the Music Librarian of the Het Brabants Orkest, Eindhoven. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Arthur H. Geissler Collection Geissler, Arthur H. (1877–1945) Scrapbooks, 1895–1928. 1.50 feet. Diplomat. Scrapbooks containing news clippings, magazine articles, government documents, pamphlets, photographs, handbills, and memorabilia accumulated by Geissler while serving as U.S. ambassador to Guatemala and reflecting events throughout Central America for the period 1922– 1928. _____________ Volume 1 This scrapbook contains newspaper clippings, magazine articles, pamphlets and handbills collected by Geissler, 1895 - 1922. This period covers Geissler’s early political career in the Republican Party in Oklahoma. Newspaper articles are from the Wichita Herald, The Oklahoma News, The Tulsa Daily, The Cleo Chieftain, The Chicago Tribune, Chicago Herald, Guthrie Leader, Daily Ardmoreite, The Houston Tribune, Oklahoma City Times, Daily Oklahoma and others. Other items and subjects covered in Volume I are as follows: • Three handbills announcing speeches to be given by Geissler for the Republican Party, 1895-1898. • Articles concerning campaigning in 1896 to get support of the “German element” of the Republican Party. • Republican Convention of Woods County to elect delegates to the Enid Convention. • May 8, 1900 - Geissler chosen as a delegate to Enid. • Wedding announcement - Arthur Geissler to Julia Henderson Adams on May 3, 1905. • Daughters of the Republic of Texas 1902-1915, of which Mrs. Geissler was president. The Pinckey Henderson Chapter. • Statehood convention 1905 - election of delegates. • Articles (1912-1918) regarding Geissler's terms as Chairman of the Republican Party in Oklahoma; 1914 - State Republican Convention, the Harris-Geissler faction; Geissler as a delegate to the Republican National Convention, Chicago, June 7, 1916. -

The Stage of the Mountains

Leopold- Franzens Universität Innsbruck The Stage of the Mountains A TRANSNATIONAL AND HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE MOUNTAINS AS A STAGE IN 100 YEARS OF MOUNTAIN CINEMA Diplomarbeit Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Mag. phil. an der Philologisch- Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck Eingereicht bei PD Mag. Dr. Christian Quendler von Maximilian Büttner Innsbruck, im Oktober 2019 Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt durch meine eigenhändige Unterschrift, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder inhaltlich den angegebenen Quellen entnommen wurden, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch nicht als Magister- /Master-/Diplomarbeit/Dissertation eingereicht. ______________________ ____________________________ Datum Unterschrift Table of Contents Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 Mountain Cinema Overview ................................................................................................... 4 The Legacy: Documentaries, Bergfilm and Alpinism ........................................................... 4 Bergfilm, National Socialism and Hollywood -

The Foreign Service Journal, December 1928

AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL Photo from E. G. Greenie TEMPLE OF HEAVEN, PEKING Vol. V "DECEMBER, 1928 No. 12 The Second, the Third —and the Tenth When an owner of a Graham Brothers Truck or Bus needs another—for replacement or to take care of business expansion—he buys another Graham .... No testimony could be more convincing. Repeat orders, constantly increasing sales, the growth of fleets—all are proof conclusive of economy, de¬ pendability, value. Six cylinder power and speed, the safety of 4-wheel brakes, the known money-making ability of Graham Brothers Trucks cause operators to buy and buy again. GRAHAM BROTHERS Detroit, U.S.A. A DIVISION QF D D n G & BRDTHE-RS C a R P . GRAHAM BROTHERS TRUCKS AND BUSES BUILT BY TRUCK DIVISION OF DODGE BROTHERS SOLD BY DODGE BROTHERS DEALERS EVERYWHERE FOREIGN JOURNAL PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION VOL. V, No. 12 WASHINGTON, D. C. DECEMBER, 1928 The Election THE final count of electoral votes cast in One of the striking features of the election was the election of November 6 shows a total the heavy popular vote for Governor Smith in of 444 votes for Herbert Hoover to 87 for spite of the overwhelming majority of electoral Gov. Alfred E. Smith, of New York, a margin votes for Hoover. The total popular vote was of 178 electoral votes over the 266 necessary for the largest ever polled in any country. The votes a majority. cast in presidential election from 1904 on, taking The popular vote has been variously estimated into account only the major parties, are as to be in the neighborhood of 20,000,000 for follows: Hoover to 14,500,000 for Smith. -

The Function of Music in Sound Film

THE FUNCTION OF MUSIC IN SOUND FILM By MARIAN HANNAH WINTER o MANY the most interesting domain of functional music is the sound film, yet the literature on it includes only one major work—Kurt London's "Film Music" (1936), a general history that contains much useful information, but unfortunately omits vital material on French and German avant-garde film music as well as on film music of the Russians and Americans. Carlos Chavez provides a stimulating forecast of sound-film possibilities in "Toward a New Music" (1937). Two short chapters by V. I. Pudovkin in his "Film Technique" (1933) are brilliant theoretical treatises by one of the foremost figures in cinema. There is an ex- tensive periodical literature, ranging from considered expositions of the composer's function in film production to brief cultist mani- festos. Early movies were essentially action in a simplified, super- heroic style. For these films an emotional index of familiar music was compiled by the lone pianist who was musical director and performer. As motion-picture output expanded, demands on the pianist became more complex; a logical development was the com- pilation of musical themes for love, grief, hate, pursuit, and other cinematic fundamentals, in a volume from which the pianist might assemble any accompaniment, supplying a few modulations for transition from one theme to another. Most notable of the collec- tions was the Kinotek of Giuseppe Becce: A standard work of the kind in the United States was Erno Rapee's "Motion Picture Moods". During the early years of motion pictures in America few original film scores were composed: D.