An Interview with Adolf Muschg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tradition Und Moderne in Der Literatur Der Schweiz Im 20. Jahrhundert

HUMANIORA: GERMANISTICA 4 HUMANIORA: GERMANISTICA 4 Tradition und Moderne in der Literatur der Schweiz im 20. Jahrhundert Beiträge zur Internationalen Konferenz zur deutschsprachigen Literatur der Schweiz 26. bis 27. September 2007 herausgegeben von EVE PORMEISTER HANS GRAUBNER Reihe HUMANIORA: GERMANISTICA der Universität Tartu Wissenschaftlicher Beirat: Anne Arold (Universität Tartu), Dieter Cherubim (Georg-August- Universität Göttingen), Heinrich Detering (Georg-August-Universität Göttingen), Hans Graubner (Georg-August-Universität Göttingen), Reet Liimets (Universität Tartu), Klaus-Dieter Ludwig (Humboldt- Universität zu Berlin), Albert Meier (Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel), Dagmar Neuendorff (Ǻbo Akademie Finnland), Henrik Nikula (Universität Turku), Eve Pormeister (Universität Tartu), Mari Tarvas (Universität Tallinn), Winfried Ulrich (Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel), Carl Wege (Universität Bremen). Layout: Aive Maasalu Einbandgestaltung: Kalle Paalits ISSN 1736–4345 ISBN 978–9949–19–018–8 Urheberrecht: Alle Rechte an den Beiträgen verbleiben bei den Autoren, 2008 Tartu University Press www.tyk.ee Für Unterstützung danken die Herausgeber der Stiftung Pro Helvetia INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Vorwort. ............................................................................................... 9 Eve Pormeister (Tartu). „JE MEHR DIFFERENZIERUNG, DESTO MEHR KULTUR“. BEGRÜSSUNG .................................................. 12 Ivana Wagner (Helsinki/Schweiz). NUR DAS GESPROCHENE WORT GILT. BEGRÜSSUNG DURCH DIE BOTSCHAFTSRÄTIN, -

Schweizer Gegenwartsliteratur

513 Exkurs 1: » ... fremd und fern wie in Grönland«• Schweizer Gegenwartsliteratur Die Schweiz, von Deutschland aus betrachtet-da entsteht das Bild einer Die Schweiz Insel: eine Insel der Stabilität und Solidität und Neutralität inmitten eines Meeres politisch-ökonomischer Unwägbarkeiten und Unwegsam- keiten. Eine Zwingburg der Finanz- und Währungshoheit, eine calvinisti- sche Einsiedelei, in der das Bankgeheimnis so gut gehütet wird wie an- dernorts kaum das Beichtgeheimnis, getragen und geprägt von einem tra ditionsreichen Patriarchat, das so konservativ fühlt wie es republikanisch handelt, umstellt von einem panoramatischen Massiv uneinnehmbarer Gipfelriesen. Ein einziger Anachronismus, durchsäumt von blauen Seen und grünen Wiesen und einer Armee, die ihresgleichen sucht auf der Welt. Ein Hort »machtgeschützter Innerlichkeit<<, mit Thomas Mann zu reden - eine Insel, von Deutschland aus betrachtet. Mag dieses Postkartenbild auch als Prospektparodie erscheinen - es entbehrt doch nicht des Körnchens Wahrheit, das bisweilen auch Pro spekte in sich tragen. >>Was die Schweiz für viele Leute so anziehend macht, daß sie sich hier niederzulassen wünschen, ist vielerlei<<, wußte schon zu Beginn der 60er Jahre ein nicht unbekannter Schweizer Schrift steller, Max Frisch nämlich, zu berichten: >>ein hoher Lebensstandard für solche, die ihn sich leisten können; Erwerbsmöglichkeit; die Gewähr eines Rechtsstaates, der funktioniert. Auch liegt die Schweiz geogra phisch nicht abseits: sofort ist man in Paris oder Mailand oder Wien. Man muß hier keine abseitige Sprache lernen; wer unsere Mundart nicht ver steht, wird trotzdem verstanden.( ...) Die Währung gilt als stabil. Die Po litik, die die Schweizer beschäftigt, bleibt ihre Familienangelegenheit.<< Kurz: >>Hier läßt sich leben, >Europäer sein<.<< Soweit das Bild- von der Schweiz aus betrachtet-, das sich die Deutschen von ihr machen. -

The Ninth Country: Handke's Heimat and the Politics of Place

The Ninth Country: Peter Handke’s Heimat and the Politics of Place Axel Goodbody [Unpublished paper given at the conference ‘The Dynamics of Memory in the New Europe: National Memories and the European Project’, Nottingham Trent University, September 2007.] Abstract Peter Handke’s ‘Yugoslavia work’ embraces novels and plays written over the last two decades as well as his 5 controversial travelogues and provocative media interventions since the early 1990s. It comprises two principal themes: criticism of media reporting on the conflicts which accompanied the break-up of the Yugoslavian federal state, and his imagining of a mythical, utopian Slovenia, Yugoslavia and Serbia. An understanding of both is necessary in order to appreciate the reasons for his at times seemingly bizarre and perverse, and in truth sometimes misguided statements on Yugoslav politics. Handke considers it the task of the writer to distrust accepted ways of seeing the world, challenge public consensus and provide alternative images and perspectives. His biographically rooted emotional identification with Yugoslavia as a land of freedom, democratic equality and good living, contrasting with German and Austrian historical guilt, consumption and exploitation, led him to deny the right of the Slovenians to national self- determination in 1991, blame the Croatians and their international backers for the conflict in Bosnia which followed, insist that the Bosnian Serbs were not the only ones responsible for crimes against humanity, and defend Serbia and its President Slobodan Milošević during the Kosovo war at the end of the decade. My paper asks what Handke said about Yugoslavia, before going on to suggest why he said it, and consider what conclusions can be drawn about the part played by writers and intellectuals in shaping the collective memory of past events and directing collective understandings of the present. -

A Study of Early Anabaptism As Minority Religion in German Fiction

Heresy or Ideal Society? A Study of Early Anabaptism as Minority Religion in German Fiction DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ursula Berit Jany Graduate Program in Germanic Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Professor Barbara Becker-Cantarino, Advisor Professor Katra A. Byram Professor Anna Grotans Copyright by Ursula Berit Jany 2013 Abstract Anabaptism, a radical reform movement originating during the sixteenth-century European Reformation, sought to attain discipleship to Christ by a separation from the religious and worldly powers of early modern society. In my critical reading of the movement’s representations in German fiction dating from the seventeenth to the twentieth century, I explore how authors have fictionalized the religious minority, its commitment to particular theological and ethical aspects, its separation from society, and its experience of persecution. As part of my analysis, I trace the early historical development of the group and take inventory of its chief characteristics to observe which of these aspects are selected for portrayal in fictional texts. Within this research framework, my study investigates which social and religious principles drawn from historical accounts and sources influence the minority’s image as an ideal society, on the one hand, and its stigmatization as a heretical and seditious sect, on the other. As a result of this analysis, my study reveals authors’ underlying programmatic aims and ideological convictions cloaked by their literary articulations of conflict-laden encounters between society and the religious minority. -

Adolf Muschg: Ein Hase Mit Offenen Ohren Für Das Ungehörte Und Unerhörte

Adolf Muschg: Ein Hase mit offenen Ohren für das Ungehörte und Unerhörte Meine sehr verehrten Damen und Herren, sehr geehrter Adolf Muschg, liebe Atsuko Muschg, Es ist mir eine Ehre, hier vor ihnen zu stehen, und es ist uns allen eine Ehre, dass Sie, wertes Publikum, so zahlreich erschienen sind, heute, wo in Zürich wieder so viel los ist, wo das Literaturhaus zum 20. Jubiläum seine Saison eröffnet, wo die Leute eine lange Nacht lang in die Museen schwärmen und in der Badi Enge ein Abend mit einer Synchronschwimm-Show veranstaltet wird. Nun, bei Synchronschwimmen sind Auftritte von Duetten, die ausschliesslich von Männern dargeboten werden, nicht unbedingt ein Renner. Vielleicht steigern wir heute ja, horribile dictu, die Quote dieser wenig beliebten Disziplin... Lassen wir also durch den Strom meiner Rede Adolf Muschg und Gottfried Keller in einem synchronen Duett schwimmen! (Und diese Synchronizität hat wahrlich nicht nur biografische Gründe, wie etwa den Umstand, dass Adolf Muschg mit einer Rede zu Keller jene Professur an der ETH für deutsche Literatur antrat, die Keller ausgeschlagen hatte, weil er, wie er seiner Mutter schrieb, lieber einen Posten hätte, „wo man nicht denken muss“. – Kann man sich Muschg eigentlich nicht denkend vorstellen?) Nun. Hier stehe ich also, und schwimme ein wenig: natürlich nicht als Elias Canetti, dem man mit Festvorträgen das Bild von Gottfried Keller so verhagelte, dass er in seinem jugendlichen und „unwissenden Hochmut“ als 14-jähriger zornig gelobte, nie ein Lokalschriftsteller wie Keller werden zu wollen, aber ich stehe hier und schwimme ein wenig, weil mir Keller in der Schule ebenfalls verhagelt wurde, weil vom Lehrer „Die drei Kammmacher“ und andere Novellen stets über den Kamm des gesunden Menschenverstandes gestrählt wurden. -

HILDEGARD EMMEL Der Weg in Die Gegenwart: Geschichte Des

Special Service ( 1973) is also his most popular dynamic movement that serves to acceler among readers of Spanish, probably be ate the flow of events and heighten ironic cause of its rollicking humor. Pantoja is a contrasts. diligent young army officer who, because of his exceptionally fine record as an ad In his dissection of Peruvian society, ministrator, is sent to Peru's northeastern Vargas Llosa satirizes the military organiza tropical region on a secret mission, the tion as well as the corruption, hypocrisy, purpose of which is to organize a squad and cliché-ridden language of his fellow ron of prostitutes referred to as "Special countrymen. A difficult book to trans Service." It seems that a series of rapes late, Captain Pantoja . loses some of has been committed by lonely soldiers its impact in the English version. Still, it stationed in this remote zone, and high- should be greatly enjoyed by American ranking officers in Lima reason that the readers with a taste for absurd humor prostitutes would satisfy sexual appetites and innovative narrative devices. and thus reduce tensions between civilians and military personnel. Although less than enthusiastic about his new post, Pantoja George R. McMurray flies to the tropical city of Iquitos where, despite many obstacles, he makes his unit the most efficient in the Peruvian army. Meanwhile, a spellbinding prophet called Brother Francisco has mesmerized a grow ing sect of religious fanatics, whose rituals include the crucifixion of animals and human beings. The novel is brought to a climax by the death of Pantoja's beautiful HILDEGARD EMMEL mistress, one of the prostitutes, and his Der Weg in die Gegenwart: Geschichte dramatic funeral oration revealing the des deutschen Romans. -

Der Präsident

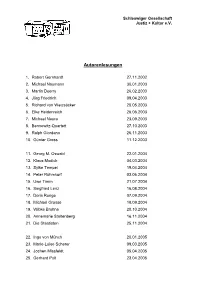

Schleswiger Gesellschaft Justiz + Kultur e.V. Autorenlesungen 1. Robert Gernhardt 27.11.2002 2. Michael Naumann 30.01.2003 3. Martin Doerry 26.02.2003 4. Jörg Friedrich 09.04.2003 5. Richard von Weizsäcker 20.05.2003 6. Elke Heidenreich 26.06.2003 7. Michael Naura 23.09.2003 8. Bennewitz-Quartett 27.10.2003 9. Ralph Giordano 26.11.2003 10. Günter Grass 11.12.2003 11. Georg M. Oswald 22.01.2004 12. Klaus Modick 04.03.2004 13. Sylke Tempel 19.04.2004 14. Peter Rühmkorf 03.06.2004 15. Uwe Timm 21.07.2004 16. Siegfried Lenz 16.08.2004 17. Doris Runge 07.09.2004 18. Michael Grosse 18.09.2004 19. Wibke Bruhns 20.10.2004 20. Annemarie Stoltenberg 16.11.2004 21. Die Staatisten 25.11.2004 22. Ingo von Münch 20.01.2005 23. Marie-Luise Scherer 09.03.2005 24. Jochen Missfeldt 05.04.2005 25. Gerhard Polt 23.04.2005 2 26. Walter Kempowski 25.08.2005 27. F.C. Delius 15.09.2005 28. Herbert Rosendorfer 31.10.2005 29. Annemarie Stoltenberg 23.11.2005 30. Klaus Bednarz 08.12.2005 31. Doris Gercke 26.01.2006 32. Günter Kunert 01.03.2006 33. Irene Dische 24.04.2006 34. Mozartabend (Michael Grosse, „Richtertrio“) ´ 11.05.2006 35. Roger Willemsen 12.06.2006 36. Gerd Fuchs 28.06.2006 37. Feridun Zaimoglu 07.09.2006 38. Matthias Wegner 11.10.2006 39. Annemarie Stoltenberg 15.11.2006 40. Ralf Rothmann 07.12.2006 41. Bettina Röhl 25.01.2007 42. -

Ein Kaffeehaus 164 VI Bürgertum Im Umbruch

Inhalt I Jahrhundertwende ARTHUR SCHNITZLER Andreas Thameyers letzter Brief 15 HUGO VON HOFMANNSTHAL Lucidor. Figuren zu einer ungeschriebenen Komödie 23 FRANK WEDEKIND Die Schutzimpfung 39 HERMANN HESSE Ein Mensch mit Namen Ziegler 46 II Abkehr vom Erbe GOTTFRIED BENN Gehirne 55 ROBERT WALSER Neujahrsblatt 6z HANS HENNY JAHNN Polarstern und Tigerin 65 Inhalt III Im Bannkreis Habsburgs und Wiens JOSEPH ROTH Seine k. und k. Apostolische Majestät ... 73 STEFAN ZWEIG Episode am Genfer See 80 ROBERT MUSIJL Die Amsel 90 ALBERT PARIS GÜTERSLOH Pan und die Dame im Kaffeehaus 111 HEIMITO VON DODERER Untergang einer Hausmeisterfamilie zu Wien im Jahre 1857 ,,.. 115 IV Zentrum Prag FRANZ WERFEL Weissenstein, der Weltverbesserer 121 FRANZ KAFKA Ein Hungerkünstler 130 MAX BROD Der Tod ist ein vorübergehender Seh wach e- zustand 143 Inhalt V Brennpunkt Berlin ALFRED DÖBLIN Kleine Alltagsgeschichte 155 ARNOLD ZWEIG »Affen« 159 WOLFGANG KOEPPEN Ein Kaffeehaus 164 VI Bürgertum im Umbruch HEINRICH MANN Sterny 171 THOMAS MANN Unordnung und frühes Leid 180 BERTOLT BRECHT Die unwürdige Greisin 225 VII Randexistenzen MARIELUISE FLEISSER Stunde der Magd 235 HANS FALLADA Ein Mensch auf der Flucht 242 8 Inhalt VIII Im Exil ALFRED DÖBLIN Das Märchen von der Technik 261 ANNA SEGHERS Das Obdach 264 HERMANN BROCH Barbara 272 IX In der Inneren Emigration REINHOLD SCHNEIDER Der Sklave des Velazquez 305 WERNER BERGENGRUEN Der Seeteufel 317 ERNST JÜNGER Die Eberjagd 329 X Das Kriegstrauma WOLFGANG BORCHERT Der viele viele Schnee 339 WOLFDIETRICH SCHNURRE Der Tick 343 Inhalt HEINRICH BÖLL Wanderer, kommst du nach Spa 349 MARIE LUISE KASCHNITZ Märzwind 361 HANS BENDER Die Wölfe kommen zurück 371 FRIEDRICH WOLF Lichter überm Graben 378 SIEGFRIED LENZ Der Abstecher 383 XI Jenseits der »Stunde Null« ILSE AICHINGER Spiegelgeschichte 395 INGEBORG BACHMANN Undine geht 406 ALFRED ANDERSCH Mit dem Chef nach Chenonceaux 417 MARTIN WALSER Es fehlt ein Wort. -

FORSCHUNGSLITERATUR: VAMPIRISMUS Kommentierte Interdisziplinäre Auswahlbibliografie

FORSCHUNGSLITERATUR: VAMPIRISMUS Kommentierte interdisziplinäre Auswahlbibliografie Clemens Ruthner (Antwerpen, Wien) Erstveröffentlichung Vorbemerkung Die vorliegende Bibliografie (Stand: Anfang 2003) kann angesichts des unüberschaubar ge- wordenen Korpus an internationaler Forschungsliteratur zum Vampir/ismus kaum Anspruch auf Vollständigkeit erheben. Es wurde aber versucht, eine für kulturwissenschaftliche Zwecke brauchbare und möglichst komplette Auswahl zu treffen, die v.a. als Überblick für alle an der Materie Interessierten im deutschsprachigen Raum gedacht ist. In Fällen, wo eine ausführliche Auflistung zu weit führen würde, wurde auf weiterführende Bibliografien und andere Infor- mationsquellen (Internet) verwiesen; auch bei Sammelbänden wurden nur in Ausnahmefäl- len einzelne Beiträge separat aufgelistet. Gelegentliche Kommentare sollen eine Benützung erleichtern; sie sind begründbar subjektiv. 1. Basistexte, Nachschlagewerke, Bibliografien, Websites, Periodika Altner, Patricia: Vampire Readings. An Annotated Bibliography. London: Scarecrow 1998 [Vam- pirtexte seit 1986, Ausz. online: http://home.earthlink.net/~paltner/vamp/excerpt.html]. Ariès, Philippe: Geschichte des Todes. Aus dem Frz. v. Horst Henschen u. Una Pfau. München: dtv 51991 [EA 1978; insbes. p. 453ff.; kulturhist. Basistext]. Bächtold-Stäubli, Hannes et al. (Hg.): Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens. 10 Bde. Berlin: de Gruyter 1927-1942 [insbes. Bd. 6, pp. 812-823; Bd. 9, pp. 570-578; volkskundl. Stan- dardwerk, enthält Infos zu den unterschiedlichen Nebenformen -

Deutsche Dichterlibraries Associated to Dandelon.Com Network

© 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May be used for personal purporses only or by Deutsche Dichterlibraries associated to dandelon.com network. Band 8 Gegenwart 01" o Philipp Reclam jun. Stuttgart J Inhalt HEIMITO VON DODERER Von Wendelin Schmidt-Dengler 9 HANS ERICH NOSSACK Von Joseph Kraus 25 MARIE LUISE KASCHNITZ Von Uwe Schweikert 32 PETER HUCHEL Von Axel Vieregg 41 REINHOLD SCHNEIDER VonRolfKühn 50 ELIAS CANETTI Von Martin Bollacher 60 WOLFGANG KOEPPEN Von Manfred Koch 71 GÜNTER EICH Von Axel Vieregg 83 MAX FRISCH Von Klaus Müller-Salget 100 HERMANN LENZ Von Klaus-Peter Philippi 122. STEFAN HEYM Von Manfred Jäger 129 ARNO SCHMIDT Von Friedhelm Rathjen 137 ALFRED ANDERSCH Von Wilfried Barner 157 6 INHALT KARL KROLOW Von Horst S. Daemmrich 164 PETER WEISS Von Heinrich Vormweg 172 WOLFGANG HILDESHEIMER Von Heinz Puknus 183 JOHANNES BOBROWSKI Von Alfred Kelletat 193 HEINRICH BÖLL Von Klaus Jeziorkowski 204 HANS BENDER Von Volker Neuhaus 223 WOLFDIETRICH SCHNURRE Von Heinz Gockel 230 PAUL CELAN Von Theo Bück 239 FRIEDRICH DÜRRENMATT Von Jan Knopf 255 WOLFGANG BORCHERT Von Siegfried Kienzle 274 HANS CARL ARTMANN VonKarlRiha 281 EUGEN GOMRINGER VonKarlRiha 289 ERNST JANDL VonRudolfDrux 301 TANKRED DORST Von Rüdiger Krohn 310 SIEGFRIED LENZ Von Hans Wagener 317 INHALT 7 MAX VON DER GRÜN Von Ingeborg Drewitz 323 HERMANN KANT Von Manfred Jäger 332 INGEBORG BACHMANN VonBerndWitte 339 MARTIN WALSER Von Martin Lüdke 350 GÜNTER GRASS Von Franz Josef Görtz 366 HEINER MÜLLER Von Uwe Wittstock 383 GÜNTER KUNERT Von Uwe Wittstock 397 CHRISTA -

E R I C H F R I E D P R E

Internationale Erich Fried Gesellschaft Seidengasse 13 Heinz Lunzer 1070 Wien | Österreich Präsident der Internationalen Tel. +43 1 5262044-0 Erich Fried Gesellschaft Fax +43 1 5262044-30 [email protected] [email protected] www.literaturhaus.at/partner/ www.literaturhaus.at E F P Der Erich Fried Preis wird seit 1990 durch die Internationale Erich Fried Gesellschaft für Literatur und Sprache vergeben. Gestiftet wird der Preis vom Bundeskanzleramt – Sektion Kunst | Kultur. Er wird nicht für ein Lebenswerk vergeben, sondern soll an „deutschsprachige Autor innen und Autoren jüngerer Jahrgänge gehen, die noch eine – hoffentlich große – litera- rische Zukunft vor sich haben.“ (Aus der Satzung der Erich Fried Gesellschaft). R R R Bisherige JurorInnen und PreisträgerInnen 1990 Hans Mayer – Christoph Hein 2003 Robert Schindel – Robert Menasse 1991 Ernst Jandl – Bodo Hell 2004 Wilhelm Genazino – Brigitte Judith Hermann, Berlin, Februar 2014 1992 Christa Wolf – Paul Parin Oleschinski © Andreas Labes 1993 Walter Jens – Robert Schindel 2005 Christoph Ransmayr – Yaak Karsunke I I E 1994 Adolf Muschg – Jörg Steiner 2006 Michael Krüger – Marcel Beyer 1995 Friederike Mayröcker – Elke Erb 2007 Ilma Rakusa – Peter Waterhouse 1996 György Konrád – Paul Nizon 2008 Katja Lange-Müller – Alois Hotschnig 1997 Ilse Aichinger – Gert Jonke 2009 Josef Winkler – Esther Dischereit 1998 Volker Braun – Bert Papenfuß 2010 Urs Widmer – Terézia Mora 1999 Elfriede Jelinek – Elfriede Gerstl 2011 Barbara Frischmuth – Thomas Stangl 2000 György Dalos – Klaus Schlesinger 2012 Lutz Seiler – Nico Bleutge C E I 2001 Brigitte Kronauer – Otto A. Böhmer 2013 Kathrin Röggla – Rainer Merkel 2002 Christina Weiss – Oskar Pastior 2014 Monika Maron – Judith Hermann HD S Friederike Mayröcker Symposium Erich Fried Preis 2014 Ein besonderer Dank gilt Christl Fallenstein für ihre Anregungen und ihre Unterstützung des Friederike Mayröcker Symposiums. -

18. Silser Hesse-Tage 15

18. silser hesse-tage 15. — 18. Juni 2017 «Im Geistigen gibt es eigentlich keine unglückliche Liebe». Hermann Hesse und Thomas Mann Die diesjährigen Hermann Hesse-Tage widmen sich einer besonders glücklichen Konstellation im Leben des Dichters: der freundschaftlichen Ver- bundenheit mit seinem großen Kollegen, dem 2 Jahre älteren Thomas Mann. In Zusammenarbeit mit der Thomas Mann-Gesellschaft Zürich beleuchten sie sowohl den Werdegang ihrer Beziehung als auch ihre ganz unterschiedliche Lebensführung und Art wie sie in ihren Werken auf die zeitgeschichtlichen Herausforderungen des 20. Jahrhunderts reagiert haben. In seiner Hommage zum 60. Geburtstag Hesses schrieb Thomas Mann: «Unter der literarischen Generation, die mit mir angetreten, habe ich ihn früh als den mir Nächsten und Liebsten erwählt und sein Wachstum mit einer Sympathie begleitet, die aus Verschiedenheiten so gut ihre Nahrung zog wie aus Ähnlichkeiten.» Und einem der wenigen Leser, der die beiden Autoren nicht gegeneinander ausspielte, antwortete er 1949: «Es hat mir Freude gemacht, dass Sie den ‚Doktor Faustus’ mit den ‚Glasperlenspiel’ zusammen nennen. Es sind in Wahrheit brüderliche Bücher. Freilich können Brüder ja sehr verschieden aussehen, sind aber doch einen Blutes.» Auch auf dieser Tagung kommen ausgewiesene Kenner und Forscher zu Wort, um die Gemeinsamkeiten und Differenzen der beiden Nobelpreisträger aufzuspüren. Den Einführungsvortrag «Lob der Herzenshöflichkeit» hält der Schriftsteller Michael Kleeberg. Zum Abschluss der Tagung wird Adolf Muschg wieder eine Bilanz der verschiedenen Beiträge mit seiner Sicht der Dinge zusammenfassen. In einer kurzweiligen Abendveranstaltung unter dem Titel «Spitzbübischer Spötter und treuherzige Nachtigall» inszeniert die Zürcher Theatergruppe Rigiblick mit authentischen Dialogen u.a. aus der Korrespondenz der beiden Autoren sowie anderen Quellen ein Hörbild von Volker Michels über die Beziehungen zwischen dem Sprössling schwäbischer Missionare und dem norddeutschen Senatorensohn aus Lübeck.