Maariv Dvar Tefillah ~ Lia Katz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Difference Between Blessing (Bracha) and Prayer (Tefilah)

1 The Difference between Blessing (bracha) and Prayer (tefilah) What is a Bracha? On the most basic level, a bracha is a means of recognizing the good that God has given to us. As the Talmud2 states, the entire world belongs to God, who created everything, and partaking in His creation without consent would be tantamount to stealing. When we acknowledge that our food comes from God – i.e. we say a bracha – God grants us permission to partake in the world's pleasures. This fulfills the purpose of existence: To recognize God and come close to Him. Once we have been satiated, we again bless God, expressing our appreciation for what He has given us.3 So, first and foremost, a bracha is a "please" and a "thank you" to the Creator for the sustenance and pleasure He has bestowed upon us. The Midrash4 relates that Abraham's tent was pitched in the middle of an intercity highway, and open on all four sides so that any traveler was welcome to a royal feast. Inevitably, at the end of the meal, the grateful guests would want to thank Abraham. "It's not me who you should be thanking," Abraham replied. "God provides our food and sustains us moment by moment. To Him we should give thanks!" Those who balked at the idea of thanking God were offered an alternative: Pay full price for the meal. Considering the high price for a fabulous meal in the desert, Abraham succeeded in inspiring even the skeptics to "give God a try." Source of All Blessing Yet the essence of a bracha goes beyond mere manners. -

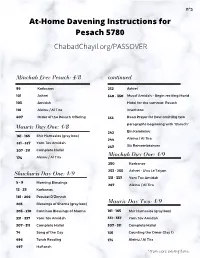

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

Bar/Bat Mitzvah Fees

www.tbsroslyn.org (516) 621-2288 (Valid Through June 30, 2020) 2019-2020 5779-5780 Rabbi Alan B. Lucas Rabbi Uri D. Allen Cantor Ofer S. Barnoy Executive Director: Donna Bartolomeo Religious School Director: Sharon Solomon Makom Director: Rabbi Uri D. Allen Name: Date: Torah portion: TABLE OF CONTENTS Greetings From Rabbi Lucas .................................................................................................... 4 Mazal Tov! ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Overall Goals Of The Bar/Bat Mitzvah Program .............................................................. 5 Educational and Religious Requirements For Bar and Bat Mitzvah ............................................................................................................ 6 Bar/Bat Mitzvah Programming .............................................................................................. 7 Trope Class .............................................................................................................................. 7 Participation In Our Mishpacha Minyan...................................................................... 7 Bar/Bat Mitzvah Family Programming ....................................................................... 7 The Mitzvah Project ............................................................................................................. 7 The Different Bar/Bat Mitzvah Ceremonies ..................................................................... -

Davening Maariv Early

Parshas Tazria April 5, 2019 Vol. I, Issue 18 DAVENING MAARIV EARLY Rabbi Yosef Melamed There are three daily prayers that Jews engage in, shacharis in the he says that mincha may only be recited until plag hamincha, one morning, mincha in the afternoon, and maariv at night. In this and a quarter hours before night (see footnote 1). The Gemara article, we will look at the custom in many shuls (synagogues) to concludes that the halacha does not exclusively follow either daven mincha and maariv one after the other. This often entails opinion. As such, one may choose to follow either opinion. davening maariv before halachic nightfall1. What is the halachic Rabeinu Tam explains that according to Rabbi Yehuda, the day, background to this practice? How about the custom to daven for prayer purposes, finishes at plag hamincha. As such, halachic mincha and maariv much earlier in the summer months or at an nighttime begins immediately following plag hamincha. The early Shabbos minyan? Are there any leniencies in this area that mishna is following the Chachamim’s view that halachic nighttime should preferably be avoided? begins at night. However, our custom to pray maariv during The first mishna in the Talmud (Brachos 2a) teaches that the daytime is based on the view of Rabbi Yehuda, that night begins correct time for reciting the nighttime Shema begins at the time immediately following plag hamincha and, as we have seen, one that kohanim who purified themselves from tumah (ritual may follow either opinion. Tosafos ask that this does not fully impurity) are allowed to eat teruma (whose consumption is answer the question; while following Rabbi Yehuda’s opinion can forbidden while in a state of tumah). -

Sim Shalom: the Perfect Prayer

Rabbi Menachem Penner Focusing on Max and Marion Grill Dean, RIETS Tefilla SIM SHALOM: THE PERFECT PRAYER e end the Amidah — makes peace in His heights.” G-d, the Torah of life, love of kindness, both on weekdays and Masekhet Derekh Eretz, Perek righteousness, blessing, mercy, life and holy days — with a Shalom no. 19 peace. tefillahW for peace. This is in keeping There are, however, multiple reasons Moreover, the closing (and opening) with the tradition of concluding our to question whether Sim Shalom is a berakhot of Shemoneh Esreh — prayers with the hope for shalom: mere request for peace. Retzei, Modim, and Sim Shalom — אמר ר' יהושע דסכנין בשם ר' לוי גדול השלום Indeed, the first half of the berakhah are not supposed to be requests at all! - שכל הברכות והתפלות חותמין בשלום: אמר רב יהודה לעולם אל ישאל אדם צרכיו :asks for more than peace קרית שמע - חותמה בשלום - "ופרוס סוכת לא בג' ראשונות ולא בג' אחרונות - אלא ָ לֹוםשִ ים ׁשטֹוָבה ּובְ ָרָכֵה חָן ו ֶֽחֶסד וְ ַרֲחמִ ים באמצעיות: שלומך". ברכת כהנים - חותמה בשלום ָע ֵֽלינּו וְ ַעָל כל יִשְ ָרֵאַל ע ָברְ ֶֽמָך׃ ֵֽכנּוָ, אבִֽ ינּוֻ, כ ָֽלנּו - שנאמר "וישם לך שלום". וכל הברכות - R’ Yehudah said: A person should not כְ ֶאָחד בְ ָאֹור כִי בְ פֶֽניָך ָאֹור נ פֶֽנָיָךַֽתָת ָֽ לנּו ה' חותמין בשלום - "עושה שלום במרומיו." ask for his needs — not during the first ֱאֹלקינּו ת ַֹורַת חיִים וְ ַֽאֲהַב ֶֽת חֶסד ּוצְ ָדָקה ּובְ ָרָכה Said R’ Yehoshua of Sachnin in the of the Amidah] and not] וְ three blessingַרֲחמִ ים וְ ַחיִים וְ ָ ׁשלֹום׃ name of R’ Levi: All the blessings and during the last three blessings. -

Halacha Newsletter Tishrei 5766 by Rabbi Y

B’H Halacha Newsletter Tishrei WWW.BeverlyHillsChabad.com 5766 by Rabbi Y. Shusterman Chabad of Northern Beverly Hills 409 N. Foothill Rd. Beverly Hills, CA 90210 (310)271-9063 (310)859-3948 We get dressed up in honor of man we say, "L'Shona The Month of Elul Rosh Hashana, being certain that Tova Tikosev V'saichosaim." To a It is customary throughout the Hashem will bless all of us with a woman we say, "L'Shona Tova month of Elul up to Yom Kippur to good and sweet year. Tikosaivi V'seichoseimie." add three chapters of Tehillim after Candlelighting time is 6:17 p.m. Following Hamotzi the Challah is the regular daily Tehillim. Before Kol (single girls light one candle.) The two dipped into honey three times. At the Nidre, before going to sleep, after Brochos are: L'Hadlik ner shel Yom beginning of the meal (after eating the Musaf and after Ne'ila we say nine Hazikaron followed by Shehechiyonu. Hamotzi) we take a piece of apple, dip chapters, thus completing the entire Maariv It is customary to say it into honey, say "Borei Pri Haetz" book of Tehillim. some Tehillim before Maariv. and the "Y'hi Ratzon" and then eat it. Maariv begins with "Shir It is customary not to eat sour or bitter Hamaalos." foods on Rosh Hashana. Througout the Aseres Yemei When bentching, Ya'ale V'yavo Teshuvah (Ten Days of Repentance) and the Horachaman are added. If one various insertions are added in the forgets to say Ya'ale V'yavo during Rosh Hashana Shmoneh Esrei. -

PESACH HOLIDAY SCHEDULE 2020 Jewishroc “PRAY-FROM-HOME” April 8 – April 16

PESACH HOLIDAY SCHEDULE 2020 JewishROC “PRAY-FROM-HOME” April 8 – April 16 During these times of social distancing, we encourage everyone to maintain the same service times AT HOME as if services were being held at JewishROC. According to Jewish Law under compelling circumstances, a person who cannot participate in the community service should make every effort to pray at the same time as when the congregation has their usual services. (All page numbers provided below are for the Artscroll Siddur or Chumash used at JewishROC) Deadline for Sale of Chametz Wed. April 1, 5:00 p.m. (Forms must be emailed to [email protected]) Search for Chametz Tues. April 7, 8:12 p.m. – see Siddur page 654 Burning/Disposal of Chametz Wed. April 8, 10:36 a.m. at the latest; recite the third paragraph on page 654 of the Siddur Siyyum for First Born: Tractate Sotah Wed. April 8, 9:00 a.m. - Held Remotely: Register no later than April 1st by sending your Skype address to [email protected]. Wednesday, April 8: Erev Pesach 1st Seder 7:15 a.m. Morning service/Shacharit: Siddur pages 16-118; 150-168. 9:00 a.m. Siyyum for first born; Register no later than April 1st by sending your Skype address to [email protected]. 10:30 a.m. Burning/disposal of Chametz; see page 654 of Artscroll Siddur. Don’t forget to recite the Annulment of the Chametz (third paragraph) 7:15 p.m. Afternoon Service/Mincha: Pray the Daily Minchah, Siddur page 232-248; Conclude with Aleinu 252-254 7:30 p.m. -

CONGREGATION B.H.H. KESSER MAARIV A.L. ANNOUNCEMENTS – July 10-11 – Pinchas Please Stay Safe and Follow Recommended Hygiene Guidance

CONGREGATION B.H.H. KESSER MAARIV A.L. ANNOUNCEMENTS – July 10-11 – Pinchas Please stay safe and follow recommended hygiene guidance. Wear masks. Keep social distancing. Anyone in a high risk category or not feeling well should stay home and be safe. Follow CDC & medical guidance. Davening Schedule While at Shul please wear your mask and follow social distancing. Please don’t move chairs/seats. For safety reasons we do not have any Talis available at shul. Bring your own. Children under age 10 are not allowed in Shul. This week’s Haftorah is for Parshat Matot (Jeremiah 1), the first of the three sad Haftarot before Tisha B’Av. Friday Early Shabbat MINCHA at 7:00 pm. If you are davening with us at 7:00 pm, your candles should be lit at about 7:25 pm. Remember to repeat Kriyat Shma after 8:45 pm. Shabbat Morning 8:45 am Shacharit. No Kiddush at shul. Sof Z’man Kriyas Shma – 9:07 am Mincha at 8:00 pm. Eat Seudat Shlisheet at home. Pirkei Avot – Chapter 6 Week of July 13: Monday-Friday Shacharit at 6:00 am. Sunday morning at 8:00 am. Daily Mincha-Maariv at 8:00 pm. Full social distance measures are in place. Upcoming Events This week is Rabbi Louis Lazovsky’s 36th Anniversary of serving as Rabbi of Kesser Maariv. While the Annual Dinner is postponed due to Covid-19, we announce the beginning of our Ad Journal Campaign honoring Rabbi Louis & Rebbetzin Saretta Lazovsky on their 36th year of leadership. The Ad Blank will be available shortly. -

Western Marble Arch

WE ARE HONOURED THIS YEAR TO BE HOSTING THE UNITED Shabbat & Yom Kippur end 7.18pm SYNAGOGUE MIDNIGHT CHORAL SELICHOT SERVICE HERE AT (Maariv, Havdalah, Shofar) WESTERN MARBLE ARCH. JOIN RABBI LIONEL ROSENFELD, CHAZAN JONNY TURGEL & THE SHABBATON CHOIR ON SATURDAY NIGHT SEPTEMBER 20, WITH KEYNOTE ADDRESS BY CHIEF RABBI Sunday 5th October EPHRAIM MIRVIS AT 11.30PM. Shacharit & Breakfast Shiur 8.30am SELICHOT DAYS Mincha & Maariv 5.30pm th th Sunday 21st September 8.10am Monday 6 – Tuesday 7 October Monday 22nd -Tuesday 23rd September 7.10am Shacharit & Breakfast Shiur 7.30am Mincha & Maariv 6.15pm Mincha & Maariv 5.30pm EREV ROSH HASHANAH EREV SUCCOT th Wednesday 24th September 6.45am Wednesday 8 October Prepare Eruv Tavshilin Shacharit & Breakfast Shiur 7.30am Mincha & Choral Maariv 6.30pm Prepare Eruv Tavshilin Candle lighting 6.40pm SUCCOT ROSH HASHANAH Candle lighting 6.08pm 1st Day - Thursday 25th September Mincha & Maariv 5.30pm 1st Day - Thursday 9th October Shacharit 8.30am Shacharit 9.15am Reading of the Torah 10.00am Mincha & Maariv 5.30pm Sounding of the Shofar 10.45am First Day ends -Candle lighting 7.07pm Children’s Service with Rebbetzen Emma Taylor 11.00am nd th Explanatory Service with Rabbi Sam Taylor 11.00am 2 Day - Friday 10 October Sermon (after Musaf) by Rabbi Lord Sacks 12.45pm Shacharit 9.15am Tashlich at Regents Park 5.30pm Mincha & Maariv 5.30pm Mincha & Choral Maariv 7.00pm Candle lighting for Shabbat 6.04pm CHOL HAMOED SUCCOT First Day ends - Candle lighting 7.39pm th 2nd Day - Friday 26th September Shabbat Chol -

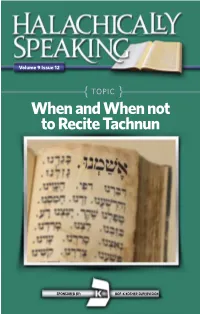

When and When Not to Recite Tachnun

Volume 9 Issue 12 TOPIC When and When not to Recite Tachnun SPONSORED BY: KOF-K KOSHER SUPERVISION Compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits Reviewed by Rabbi Benzion Schiffenbauer Shlita All Piskei Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita are HALACHICALLY SPEAKING Halachically Speaking reviewed by Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita is a monthly publication compiled by Rabbi Moishe SPONSORED: Dovid Lebovits, a former chaver kollel of Yeshiva Torah לרפואה שלמה Vodaath and a musmach of .Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita מרת רחל בת פעסיל Rabbi Lebovits currently SPONSORED: works as the Rabbinical Administrator for the KOF-K לרפואה שלמה Kosher Supervision. חיים צבי בן אסתר Each issue reviews a different area of contemporary halacha with an emphasis on practical applications of the principles discussed. Significant time is spent ensuring the inclusion of all relevant shittos on each topic, as well as the psak of Harav Yisroel Belsky, Shlita on current issues. WHERE TO SEE Design by: HALACHICALLY SPEAKING Halachically Speaking is distributed to many shuls in SRULY PERL 845.694.7186 Flatbush, Lakewood, Five Towns, Far Rockaway, and Queens. It is sent via email to subscribers across the world. SUBSCRIBE To sponsor an issue please call FOR FREE 718-744-4360 and view archives @ © Copyright 2013 www.thehalacha.com by Halachically Speaking When and When not ח.( )ברכות to Recite Tachnun בלבד... הלכה אין לו להקב"ה בעולמו אלא ד' אמות של here are many days of the year where tachnun is not recited. Some times one is in a shul and there Twill be a bris on that day and no tachnun is said. -

Davening Time-2021-09.Xlsx

YOUNG ISRAEL OF OCEANSIDE DAVENING SCHEDULE September 2021 Elul 5781 ‐ Tishrei 5782 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 8/29 21 Elul 8/30 22 Elul 8/31 23 Elul 1 24 Elul 2 25 Elul 3 26 Elul 4 27 Elul Rabbi's Parsha Class: 8:15 AM Shacharit: 7:00/8:00 AM Shacharit: 6:10/7:25 AM Shacharit: 6:20/7:25 AM Shacharit: 6:20/7:25 AM Shacharit: 6:10/7:25 AM Shacharit: 6:20/7:25 AM Shacharit: 7:30, 8:45 AM (Selichot 7:00 AM) (Selichot 7:00 AM) (Selichot 7:00 AM) (Selichot 7:00 AM) (Selichot 7:00 AM) Women's Parsha Class: 5:50 Mincha/Maariv: 7:15 Mincha/Maariv: 7:15 Mincha/Maariv: 7:15 Mincha/Maariv: 7:15 Mincha/Maariv: 7:15 Candle Lighting: 7:04 Rabbi's Gemara Class: 6:05 Mincha: 6:50 Mincha/Maariv: 7:00 Rabbi's Class/Seudah Shlishit: 7:15 Maariv/Selichot‐YIO: 9 PM Maariv/Selichot‐YIO: 9 PM Maariv/Selichot‐YIO: 9 PM Maariv/Selichot‐YIO: 9 PM Maariv/Selichot‐YIO: 9 PM Maariv: 7:58 Shabbat Ends: 8:03 Nitzavim Selichot ONLY: 9:45 5 28 Elul 6 29 Elul 7 1 Tishrei 8 2 Tishrei 9 3 Tishrei 10 4 Tishrei 11 Shabbat Shuva 5 Tishrei "Naitz " Shacharit: 6:00 AM "Naitz " Shacharit: 6:00 AM Fast Begins: 5:06 AM Rabbi's Parsha Class: 8:15 AM Shacharit: 7:00 & 8:00 AM Shacharit: 7:00 & 8:00 AM Shacharit: 8:00 AM Shacharit:Beit M. -

The Shabbat Bar/Bat Mitzvah Service

חֲנְֹך לַנַעַר עַל־פִּידַרְ ּכֹו גַם ּכִּ י־יַזְקִּ ין לֹא־יָסּור מִּ מֶּ נָה “Train up a child in the way he should go and even when he is old he will not depart from it.” – Proverbs 22:6 Guidebook for Bar / Bat Mitzvah Shelter Rock Jewish Center Prepared June 2014 Updated for website August 2016 272 Shelter Rock Road • Roslyn, NY 11576 516-741-4305 • www.srjc.org TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 5 NOTES FROM RABBI COHEN .................................................................................................. 6 BAR/BAT MITZVAH TRAINING WITH CANTOR ........................................................................ 7 A SHORT HISTORY OF THE BAR/BAT MITZVAH ....................................................................... 8 GOALS OF THE BAR/BAT MITZVAH PROGRAM. .................................................................... 10 REQUIREMENTS FOR SHABBAT MORNING BAR/BAT MITZVAH AT SRJC ................................ 12 THE DATE ............................................................................................................................ 12 THE BAR/BAT MITZVAH AT SRJC .......................................................................................... 15 The Shabbat Bar / Bat Mitzvah Service ................................................................................................................. 16 Weekdays when Torah is read ..............................................................................................................................