A North Indian Classical Dance Form: Lucknow Kathak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

June 2017.Pmd

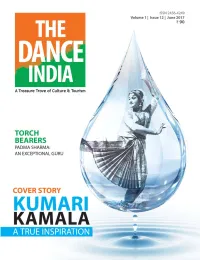

Torch Bearers Padma Sharma: CONTENTSCONTENTS An Exceptional Guru Cover 10 18 Story Rays of Kumari Kamala: 34 Hope A True Inspiration Dr Dwaram Tyagaraj: A Musician with a Big Heart Cultural Beyond RaysBulletin of Hope Borders The Thread of • Expressions34 of Continuity06 Love by Sri Krishna - Viraha Reviews • Jai Ho Russia! Reports • 4th Debadhara 52 Dance Festival • 5 Art Forms under One Roof 58 • 'Bodhisattva' steals the show • Resonating Naatya Tarang • Promoting Unity, Peace and Indian Culture • Tyagaraja's In Sight 250th Jayanthi • Simhapuri Dance Festival: A Celebrations Classical Feast • Odissi Workshop with Guru Debi Basu 42 64 • The Art of Journalistic Writing Tributes Beacons of light Frozen Mandakini Trivedi: -in-Time An Artiste Rooted in 63 Yogic Principles 28 61 ‘The Dance India’- a monthly cultural magazine in "If the art is poor, English is our humble attempt to capture the spirit and culture of art in all its diversity. the nation is sick." Editor-in-Chief International Coordinators BR Vikram Kumar Haimanti Basu, Tennessee Executive Editor Mallika Jayanti, Nebrasaka Paul Spurgeon Nicodemus Associate Editor Coordinators RMK Sharma (News, Advertisements & Subscriptions) Editorial Advisor Sai Venkatesh, Karnataka B Ratan Raju Kashmira Trivedi, Thane Alaknanda, Noida Contributions by Lakshmi Thomas, Chennai Padma Shri Sunil Kothari (Cultural Critic) Parinithi Gopal, Sagar Avinash Pasricha (Photographer) PSB Nambiar Sooryavamsham, Kerala Administration Manager Anurekha Gosh, Kolkata KV Lakshmi GV Chari, New Delhi Dr. Kshithija Barve, Goa and Kolhapur Circulation Manager V Srinivas Technical Advise and Graphic Design Communications Incharge K Bhanuji Rao Articles may be submitted for possible publication in the magazine in the following manner. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full -

Just Dance / जट डाॊस, Boogie Woogie / फूगी वूगी

PAPER 6 DANCE IN INDIA TODAY, DANCE-DRAMAS, CREATIVITY WITHIN THE CLASSICAL FORMS, INDIAN CLASSICAL DANCE IN DIASPORA (USA, UK, EUROPE, AUSTRALIA, ETC.) MODULE 15 KATHAK AS VOCATION For long has dance been a vocation in India. Both men and women have been ritual dance specialists associated with temples and monasteries. The story of the Devadasis, Maibis and Maharis / भहायी is well known. There are monk dancers in Assam called bhakats who are examples of males who dedicate their lives to the performance of dance as an offering and a ritual in a temple. There were also public platforms, where for entertainment purposes men and women danced. Chhau / छाऊ, Raibenshe / यैफᴂशे, Yakshagana / मऺगान, Kuchipudi / कु चिऩुड़ी, etc are examples of how and when traditionally males’ danced. Some of the women belonging to specific communities were associated with dancing for entertainment. For instance the Kalbelia / कारफेलरमा, Rai / याइ and Bedia / फेडडमा women were for centuries known to dance for entertainment. It is believed that the Bedia women danced for the laborers from different parts of the word who had collected at Taj Ganj at the time of the building of the Taj Mahal. Later they were among the communities and tribes that entertained the British troupes. Today many Bedia girls are among the Bar dancers of Mumbai. Apart from these girls there was also a group of traditional performers called by various names- Tawaif / तवामप, baijis / फाईजी, 1 etc. They were a whole range of professional dancing girls, some so talented that they had access to the highest centres of power, like the palace and the courtly setting, and were well integrated with the royals and the aristocracy. -

Cultural Geography of Kathak Dance: Streams of Tradition and Global Flows*

Cracow Indological Studies vol. XVIII (2016) 10.12797/CIS.18.2016.18.04 Katarzyna Skiba [email protected] (Jagiellonian University, Kraków) Cultural Geography of Kathak Dance: Streams of Tradition and Global Flows* SUMMARY: The article deals with the modern history of Kathak, explored from regional perspectives. It focuses on the Lucknow gharānā (“school”) of Kathak, which sprung up mainly in courts and salons of colonial Avadh as a product of Indo- Islamic culture. The paper investigates how the shift of hereditary artists from Lucknow to Delhi affected their tradition in newly founded, state-supported institutions. It also examines various trends of further modernization of Kathak in globalized, metropolitan spaces. The tendency of Sanskritization in national dance institutes (Kathak Kendra) is juxtaposed with the preservation of ‘traditional’ form in dance schools of Lucknow (nowadays becoming more provincial locations of Kathak tradition) and innovative / experimental tendencies. The impact of regional culture, economic conditions and cosmopolitanism are regarded as important factors reshaping Kathak art, practice and systems of knowledge transmission. The paper is based on ethnographic fieldwork, combined with historical research, conducted in the period 2014–2015. KEYWORDS: classical Indian dance, Kathak, Lucknow gharānā, Indo-Islamic culture. * Much of the data referred to in this paper comes from the interviews with Kathak artists and dance historians which I conducted in India in 2014–2015 as part of two research projects: The Role of Sanskrit Literature in Shaping the Classical Dance Traditions in India (funded by École française d’Extrême-Orient), and Transformation of the Classical Indian Dance Kathak in the Context of Socio-cultural Changes (funded by National Science Center in Poland/NCN on the basis of decision no. -

![KATHAK DANCE IKSV X-XI 2 IKSV X-XI 2 Ch-,- Izfkeo’Kz] Ijh{Kk& 2011 B.A](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0048/kathak-dance-iksv-x-xi-2-iksv-x-xi-2-ch-izfkeo-kz-ijh-kk-2011-b-a-2230048.webp)

KATHAK DANCE IKSV X-XI 2 IKSV X-XI 2 Ch-,- Izfkeo’Kz] Ijh{Kk& 2011 B.A

IKSV X-XI 1 IKSV X-XI 1 BA/ M A/ M.DANCE KATHAK DANCE IKSV X-XI 2 IKSV X-XI 2 ch-,- izFkeo’kZ] ijh{kk& 2011 B.A. I YEAR, EXAM. 2011 dFkd u`R; KATHAK DANCE Paper-I izFke iz’u i= Time: 3 Hrs. Max. M. 75 Min.M. 25 le;&3 ?k.Vs iw.kkZad&75 U;wuakd&25 Note : Attempt any five questions. All questions carry equal marks. *** Vhi%& dksbZ iakp iz’u gy dhft;s A lHkh iz’uksa ds vad leku gSa A 1. Write in brief history of Kathak Dance. $$$ 2. Explain the importance of Guru-Vandana and 1- dFkd u`R; dk laf{kIr bfrgkl fyf[k;s A Mangalacharan in Kathak Dance. 2- dFkd u`R; esa xq#&oanuk ,oa eaxykpj.k dk egRo le>kb;s A 3. Write down the life sketch of Pt. Bindadin Maharaj 3- ia0 fcUnknhu egkjkt dk thou ifjp; fy[krs gq, dFkd along with his contribution to Kathak Dance. u`R; dks muds ;ksxnku dk o.kZu dhft;s A 4. Describe Greeva Bhed according to Abhinaya Darpan. 4- vfHku; niZ.k ds vuqlkj xzhok Hksnksa dk o.kZu dhft;s A 5. Write the definition of any five of the following:- 5- fuEufyf[kr esa fdUgha ik¡p dks ifjHkkfÔr dhft;s%& Tatkar, Hastak, Sam, Aavartan, Theka, Tal, Matra. rRdkj] gLrd] le] vkorZu] Bsdk] rky] ek=k A 6. According to Abhinaya Darpan write the names of 6- vfHku; niZ.k ds vuqlkj vla;qDr gLr eqnzkvksa dks ’yksd Asamyukta Hasta Mudra with shloka and describe lfgr uke fy[krs gq, fdUgha ik¡p dks fofu;ksx lfgr le>kb;s A any five hastas with viniyoga. -

The Shadow and the Arc Light: Finding the Female Workforce in Bombay Cinema

E-CineIndia July-September 2020 ISBN: 2582-2500 Article Madhuja Mukherjee The Shadow and the Arc Light: Finding the Female Workforce in Bombay Cinema Abstract: This paper is connected to broader research concerning gender, labour and the Indian film industry, and develops from my on-going audio-visual project titled ”The shadow and the arc light”. While it is linked with my previous book project, ‘Voices of the Talking Stars’ (2017) involving women/ work and cinema dynamics, the attempt here is to reclaim feminist narratives from the historical debris and amnesia, in the context of contemporary and emergent feminist historiography. Furthermore, while certain degree of research has been conducted on women as ‘directors’, my purpose here is not to posit women as ‘auteurs’; contrarily, I aspire draw attention to the problems of historical readings which, generally speaking, have been greatly influenced by studies of periods, styles, movements and (great) masters, even though, more recently newer research have examined industrial conditions, cinematic transactions across regions, media histories, and so on. Consequently, my aim is to shift the focus to subjects of labour, and bring to light the characteristics of film work, and enquire where is the female figure on the elusive credit lists? Therefore, I call attention to a historical lacuna, which provokes us to rethink film historiography, and highlight the nature of filmic work and underscore the (un-credited) work done by women, in multiple capacities, during the last century. The ‘women’s question’ thus, urges us to rethink methods of writing histories for cinema. The purpose of this paper consequently is two fold -- first, to understand the nature filmic work, and secondly, to locate the shadow of the women worker in the archives of cinema. -

INSIDE Aekalavya Awardees Lasyakala & Artists Guru Deba Prasad Nrutyadhara & Artists a Vista of Indian Art, Culture

1st Edition of A Vista of Indian Art, Culture and Dance INSIDE Aekalavya Awardees Lasyakala & Artists Guru Deba Prasad Nrutyadhara & Artists Channel Partners Transactions Per Month Employees Developer Clients Happy Customers Monthly Website Visitors Worth of Property Sold India Presence : Ahmedabad | Bengaluru | Chennai | Gurugram| Hyderabad | Jaipur Kolkata | Lucknow | Mumbai | Navi Mumbai | New Delhi | Noida | Pune | Thane | Vishakhapatnam | Vijayawada Global Presence : Abu Dhabi | Bahrain| Doha | Dubai | Hong Kong | Kuwait | Muscat | Melbourne | Sharjah Singapore | Sydney | Toronto WWW.SQUAREYARDS.COM SY Solutions PTE Limited, 1 Raffles Place, Level 19-61, One Raffles Place, Tower 2, Singapore - 048616 Message J P Jaiswal, Chairman & Managing Director, Peakmore International Pte Ltd Past Director, Singapore Indian Chamber of Commerce & Industry (2014-2018) Dear Friends, It gives me immense pleasure to congratulate Guru Deba Prasad Nrutyadhara, Singapore and the organizers for bringing the popular production Aekalavya Season 11. Congratulations to the esteemed team of Lasyakala for co-producing this beautiful act in classical dance form. It’s also a matter of joy that Padmabibhushan Shilpiguru Mr Raghunath Mohapatra shall grace the program as Chief Guest. I also congratulate to all Aekalavya Season-11 Awardees and extend my best wishes to all the performers. My heartfelt best wishes for a successful performance and wish a joyful evening to all audience. Finally, once again, I thank the organizers for all the effort -

Cultural Geography of Kathak Dance: Streams of Tradition and Global Flows*

Cracow Indological Studies vol. XVIII (2016) 10.12797/CIS.18.2016.18.04 Katarzyna Skiba [email protected] (Jagiellonian University, Kraków) Cultural Geography of Kathak Dance: Streams of Tradition and Global Flows* SUMMARY: The article deals with the modern history of Kathak, explored from regional perspectives. It focuses on the Lucknow gharānā (“school”) of Kathak, which sprung up mainly in courts and salons of colonial Avadh as a product of Indo- Islamic culture. The paper investigates how the shift of hereditary artists from Lucknow to Delhi affected their tradition in newly founded, state-supported institutions. It also examines various trends of further modernization of Kathak in globalized, metropolitan spaces. The tendency of Sanskritization in national dance institutes (Kathak Kendra) is juxtaposed with the preservation of ‘traditional’ form in dance schools of Lucknow (nowadays becoming more provincial locations of Kathak tradition) and innovative / experimental tendencies. The impact of regional culture, economic conditions and cosmopolitanism are regarded as important factors reshaping Kathak art, practice and systems of knowledge transmission. The paper is based on ethnographic fieldwork, combined with historical research, conducted in the period 2014–2015. KEYWORDS: classical Indian dance, Kathak, Lucknow gharānā, Indo-Islamic culture. * Much of the data referred to in this paper comes from the interviews with Kathak artists and dance historians which I conducted in India in 2014–2015 as part of two research projects: The Role of Sanskrit Literature in Shaping the Classical Dance Traditions in India (funded by École française d’Extrême-Orient), and Transformation of the Classical Indian Dance Kathak in the Context of Socio-cultural Changes (funded by National Science Center in Poland/NCN on the basis of decision no. -

A Study on History of Indian Classical Dancers Mallika Sarabhai & Pandit Birju Maharaj Kunsoth Manjula PG College Subedari Kakathiya University

International Journal of Research e-ISSN: 2348-6848 p-ISSN: 2348-795X Available at https://edupediapublications.org/journals Volume 04 Issue 08 July 2017 A Study on History of Indian Classical Dancers Mallika Sarabhai & Pandit Birju Maharaj Kunsoth Manjula PG College subedari Kakathiya University Abstract: As you can see India is a very intricate culture full of diversities which makes our culture unique as a whole. and I hope that by reading this piece you will understand that dance is full of passion and technique. As Rukmini Devi says “Many people have said many things. I can only say I did not consciously go after dance. It found me." (wikiquotes) You understand that dance is universal. There are two main forms of dances 0 classical and folk. The origin of classical dances are the Hindu temples, Some famous classical dances of India are Bharat Natyam, Kathakali, Manipuri, Kathak and Odissi. The rules and principles of classical dances were laid in the Natyashstra by BharatMuni, ages ago. Folk dance is a traditional dance of the common people of a reign. No rigid rules are followed in folk dances. The Sangeed Natak Akademi and other institutes promote both classical and folk dances. Introduction: in many socio-developmental projects initiated by the United Nations. Mallika Indian classical dance has a distinct Sarabhai has also received the "French character that reflects the great cultural and Palme D'or'', the highest civilian award of traditional endeavor. The forms of Indian France. dance have transcended beyond the fences and socio-cultural hindrances. Exponents of the Indian classical dance believe that it has the caliber of creating a new and disciplined lifestyle. -

Classical Singing / Playing • भरतमुनि का िाट्यशास्त्र' Composed In

Classical singing / playing • भरतमुनि का िाट्यशास्त्र’ composed in ancient period is the 'Bible of the musicians’ of North India. • Mahaprabhu Vallabhacharya established a पुनि संप्रदाय in Mathura-Vrindavan. • Vitthal Nath established Krishnaleela Gaan Panth (कृष्णलीला गाि संप्रदाय) • In Ashtachhap poets were - Surdas, Nand das, Parmandand das, Kumbhna das, Chaturbuja das, Chhit Swami, Govind Swami and Krishnadas. • Swami Haridas, the propagater of the Sakhi Panth, composed 'Shrikalimal' and 'Ashtashash'. • Swami Haridas had trained Tansen on Deepak Raag, Baiju Bawra on Megh Raag, and Gopal Nayak on Maalakauns Raag. • Amir Khusro had mixed famous Iranian music raags in Indian Raag. • Modu Khan and Bakshur Khan propagated the Lucknow Gharana of Tabla. • Modu Khan's disciple Pt. Ramsahay propagated the Banaras VaJ Gharana. • The Agra Gharana is also called the Kawwal bachcha Gharana. • Singer Ustad Fayaz Khan belongs to Agra Gharana • Akbar's court singer Sujhan Khan is said to be the originator of the Agra Gharana. • Bahram Khan of Saharanpur Gharana was given the title of Pandit. Classical dance • Sitara Devi and Alkhananda Devi of Varanasi received fame in the field of Kathak dance. • Following are the famous uttar Pradesh players of respective instruments Violin playing: Mrs N. Rajam; Shehany Vadan: Ustad Bismillah Khan; Sitar Vandan: Pt-Ravi Shankar, Rajbhan Singh, Ustad Mushtaq Ali Khan and in Dance: Uday Shankar and Gipikrishna. • Kathak style of dance originated in Uttar Pradesh • Bindaddin, Shambhu Maharaj, Lachhu Maharaj and Birju Maharaj were famous practitioners Kathak. Folk dance • 'Charakula' is a pitcher dance which is the folk dance of Brajbhoomi. • 'Pai Danda' dance is performed by Aheers of Bundelkhand. -

Indian Art,Culture & Heritage-Gktoday

Civil Services Examination 2013 Conventional General Studies-39 www.gktoday.in Target 2013 Indian Culture- Comepndium of Basics 1 1. Religions Religion has been an important part of India’s culture throughout its history. Religious diversity and religious tolerance are both established in the country by law and custom. A vast majority of Indians (over 93%) associate themselves with a religion. Four of the world's major religious traditions; Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism are originated at India. These religions are also called as ‘Eastern Religions’. 1. Hinduism The word Hindu is derived from the Sanskrit name Sindhu for the Indus River. With around 1 billion followers, Hinduism is the third largest religion in the world after Christianity and Islam. Hinduism is considered as the oldest religion of the World originating around 5000 years ago. It is the predominant spiritual following of the Indian subcontinent, and one of its indigenous faiths. Hinduism is a conglomeration of distinct intellectual or philosophical points of view, rather than a rigid common set of beliefs. Hinduism was spread through parts of South-eastern Asia, China, Korea, and Japan. Hindus worship a god with different forms. Evolution The origin of Hinduism dates back to prehistoric times. Some of the important evidences of prehistoric times: • Mesolithic rock paintings depicting dances and rituals gives evidence attesting to prehistoric religion in the Indian "subcontinent". • Neolithic pastoralists inhabiting the Indus River Valley buried their dead in a manner suggestive of spiritual practices that incorporated notions of an afterlife and belief in magic. • Other Stone Age sites, such as the Bhimbetka rock shelters in central Madhya Pradesh and the Kupgal petroglyphs of eastern Karnataka, contain rock art portraying religious rites and evidence of possible ritualised music.