Just Dance / जट डाॊस, Boogie Woogie / फूगी वूगी

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Classical Dance Is a Relatively New Umbrella Term for Various Codified Art Forms Rooted in Natya, the Sacred Hindu Musica

CLASSICAL AND FOLK DANCES IN INDIAN CULTURE Palkalai Chemmal Dr ANANDA BALAYOGI BHAVANANI Chairman: Yoganjali Natyalayam, Pondicherry. INTRODUCTION: Dance in India comprises the varied styles of dances and as with other aspects of Indian culture, different forms of dances originated in different parts of India, developed according to the local traditions and also imbibed elements from other parts of the country. These dance forms emerged from Indian traditions, epics and mythology. Sangeet Natak Akademi, the national academy for performing arts, recognizes eight distinctive traditional dances as Indian classical dances, which might have origin in religious activities of distant past. These are: Bharatanatyam- Tamil Nadu Kathak- Uttar Pradesh Kathakali- Kerala Kuchipudi- Andhra Pradesh Manipuri-Manipur Mohiniyattam-Kerala Odissi-Odisha Sattriya-Assam Folk dances are numerous in number and style, and vary according to the local tradition of the respective state, ethnic or geographic regions. Contemporary dances include refined and experimental fusions of classical, folk and Western forms. Dancing traditions of India have influence not only over the dances in the whole of South Asia, but on the dancing forms of South East Asia as well. In modern times, the presentation of Indian dance styles in films (Bollywood dancing) has exposed the range of dance in India to a global audience. In ancient India, dance was usually a functional activity dedicated to worship, entertainment or leisure. Dancers usually performed in temples, on festive occasions and seasonal harvests. Dance was performed on a regular basis before deities as a form of worship. Even in modern India, deities are invoked through religious folk dance forms from ancient times. -

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

Annual Report 2014 - 2015 Ministry of Culture Government of India

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 - 2015 MINISTRY OF CULTURE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Annual Report 2014-15 1 Ministry of Culture 2 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site Annual Report 2014-15 CONTENTS 1. Ministry of Culture - An Overview – 5 2. Tangible Cultural Heritage 2.1 Archaeological Survey of India – 11 2.2 Museums – 28 2.2a National Museum – 28 2.2b National Gallery of Modern Art – 31 2.2c Indian Museum – 37 2.2d Victoria Memorial Hall – 39 2.2e Salar Jung Museum – 41 2.2f Allahabad Museum – 44 2.2g National Council of Science Museum – 46 2.3 Capacity Building in Museum related activities – 50 2.3a National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology – 50 2.3.b National Research Laboratory for conservation of Cultural Property – 51 2.4 National Culture Fund (NCF) – 54 2.5 International Cultural Relations (ICR) – 57 2.6 UNESCO Matters – 59 2.7 National Missions – 61 2.7a National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities – 61 2.7b National Mission for Manuscripts – 61 2.7c National Mission on Libraries – 64 2.7d National Mission on Gandhi Heritage Sites – 65 3. Intangible Cultural Heritage 3.1 National School of Drama – 69 3.2 Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts – 72 3.3 Akademies – 75 3.3a Sahitya Akademi – 75 3.3b Lalit Kala Akademi – 77 3.3c Sangeet Natak Akademi – 81 3.4 Centre for Cultural Resources and Training – 85 3.5 Kalakshetra Foundation – 90 3.6 Zonal cultural Centres – 94 3.6a North Zone Cultural Centre – 95 3.6b Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre – 95 3.6c South Zone Cultural Centre – 96 3.6d West Zone Cultural Centre – 97 3.6e South Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6f North Central Zone Cultural Centre – 98 3.6g North East Zone Cultural Centre – 99 Detail from Rani ki Vav, Patan, Gujarat, A World Heritage Site 3 Ministry of Culture 4. -

Assets.Kpmg › Content › Dam › Kpmg › Pdf › 2012 › 05 › Report-2012.Pdf

Digitization of theatr Digital DawnSmar Tablets tphones Online applications The metamorphosis kingSmar Mobile payments or tphones Digital monetizationbegins Smartphones Digital cable FICCI-KPMG es Indian MeNicdia anhed E nconttertainmentent Tablets Social netw Mobile advertisingTablets HighIndus tdefinitionry Report 2012 E-books Tablets Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities 3D exhibition Digital cable Portals Home Video Pay TV Portals Online applications Social networkingDigitization of theatres Vernacular content Mobile advertising Mobile payments Console gaming Viral Digitization of theatres Tablets Mobile gaming marketing Growing sequels Digital cable Social networking Niche content Digital Rights Management Digital cable Regionalisation Advergaming DTH Mobile gamingSmartphones High definition Advergaming Mobile payments 3D exhibition Digital cable Smartphones Tablets Home Video Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Vernacular content Portals Mobile advertising Social networking Mobile advertising Social networking Tablets Digital cable Online applicationsDTH Tablets Growing sequels Micropayment Pay TV Niche content Portals Mobile payments Digital cable Console gaming Digital monetization DigitizationDTH Mobile gaming Smartphones E-books Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Mobile advertising Mobile gaming Pay TV Digitization of theatres Mobile gamingDTHConsole gaming E-books Mobile advertising RegionalisationTablets Online applications Digital cable E-books Regionalisation Home Video Console gaming Pay TVOnline applications -

FIJI DAY CELEBRATIONS Fiji Celebrates 43Rd Anniversary of Regaining Independence from Great Britain

“Serving our Community SUNIL DESAI www.fijitimescanada.com Phone: 604.909.4088 for over 30 years” Sales Manager B: 604-987-5231 C: 778-868-5757 800 AUTOMALL DR NORTH VANCOUVER NORTH SHORE AUTOMALL [email protected] CANADA'S WEEKLY NEWSPAPER SINCE 2006 October 11, 2013 FIJI DAY CELEBRATIONS Fiji celebrates 43rd anniversary of regaining independence from Great Britain. Let us not forget our past heroes. Not only those have who died but we need new kinds of heroes today: individuals who can take the lead in many diverse fields and lead lives that younger Fijians can look up to as role models. Today, we celebrate the continuing progress on the road to a better Fiji. Have a blessed and safe Fiji Day celebration. Warm wishes from USA US President Barack Obama sent a congratulatory note to the people of Fiji in recognition of the nation's 43 years of independence. "On behalf of the American people, I offer my warmest congratulations to the people of the Republic of Fiji as you commemorate the 43rd anniversary of your nation's independence on October 10," President Obama said in the message sent to the US Embassy in Suva. He said the US had much appreciation for the people of Fiji, adding he hopes to continue to strengthen ties with Fiji in the near future. Let us all be reminded that it is offices. Schools across the country have Pacific) Ministerial Meeting. "It is my fervent hope that relations important that we not only celebrate, organised activities to mark the occasion. -

Karan Johar Shahrukh Khan Choti Bahu R. Madhavan Priyanka

THIS MONTH ON Vol 1, Issue 1, August 2011 Karan Johar Director of the Month Shahrukh Khan Actor of the Month Priyanka Chopra Actress of the Month Choti Bahu Serial of the Month R. Madhavan Host of the Month Movie of the Month HAUNTED 3D + What’s hot Kids section Gadget Review Music Masti VAS (Value Added Services) THIS MONTH ON CONTENTS Publisher and Editor-in-Chief: Anurag Batra Editorial Director: Amit Agnihotri Editor: Vinod Behl Directors: Nawal Ahuja, Ritesh Vohra, Kapil Mohan Dhingra Advisory Board Anuj Puri, (Chairman & Country Head, Jones Lang LaSalle India) Laxmi Goel, (Director, Zee News & Chairman, Suncity Projects) Ajoy Kapoor (CEO, Saffron Real Estate Management) Dr P.S. Rana, Ex-C( MD, HUDCO) Col. Prithvi Nath, (EVP, NAREDCO & Sr Advisor, DLF Group) Praveen Nigam, (CEO, Amplus Consulting) Dr. Amit Kapoor, (Professor in Strategy and nd I ustrial Economics, MDI, Gurgoan) Editorial Editorial Coordinating Editor : Vishal Duggal Assistant Editor : Swarnendu Biswas da con parunt, ommod earum sit eaqui ipsunt abo. Am et dias molup- Principal Correspondent : Vishnu Rageev R tur mo beressit rerum simpore mporit explique reribusam quidella Senior Correspondent : Priyanka Kapoor U Correspondents : Sujeet Kumar Jha, Rahul Verma cus, ommossi dicte eatur? Em ra quid ut qui tem. Saecest, qui sandiorero tem ipic tem que Design Art Director : Jasper Levi nonseque apeleni entustiori que consequ atiumqui re cus ulpa dolla Sr. Graphic Designers : Sunil Kumar preius mintia sint dicimi, que corumquia volorerum eatiature ius iniam res Photographe r : Suresh Gola cusapeles nieniste veristo dolore lis utemquidi ra quidell uptatiore seque Advertisment & Sales nesseditiusa volupta speris verunt volene ni ame necupta consequas incta Kapil Mohan Dhingra, [email protected], Ph: 98110 20077 sumque et quam, vellab ist, sequiam, amusapicia quiandition reprecus pos 3 Priya Patra, [email protected], Ph: 99997 68737, New Delhi Sneha Walke, [email protected], Ph: 98455 41143, Bangalore ute et, coressequod millaut eaque dis ariatquis as eariam fuga. -

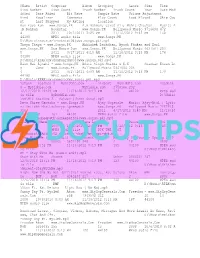

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc Number Disc Count Track Number Track Count Year Date Mod Ified Date

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc Number Disc Count Track Number Track Count Year Date Mod ified Date Added Bit Rate Sample Rate Volume Adjustment Kind Equalizer Comments Play Count Last Played Skip Cou nt Last Skipped My Rating Location Kun Faya Kun www.Songs.PK A.R Rahman, Javed Ali, Mohit Chauhan Music: A .R Rahman Rockstar www.Songs.PK Bollywood Music 9718690 472 4 2011 10/2/2011 3:25 PM 11/16/2012 9:13 PM 160 44100 MPEG audio file www.Songs.PK D:\Music\rockstar\rockstar04(www.songs.pk).mp3 Thayn Thayn www.Songs.PK Abhishek Bachchan, Ayush Phukan and Earl www.Songs.PK Dum Maaro Dum www.Songs.PK Bollywood Music 4637567 204 5 2011 3/17/2011 4:19 AM 11/16/2012 9:13 PM 174 44100 MPEG audio file www.Songs.PK D:\Music\RFAK\nm\dummaardum05(www.songs.pk).mp3 Kaun Hai Ajnabi www.Songs.PK Aditi Singh Sharma & K.K Shankar Ehsan Lo y Game www.Songs.PK Bollywood Music 5461864 238 4 2011 3/27/2011 4:08 AM 11/16/2012 9:13 PM 173 44100 MPEG audio file www.Songs.PK D:\Music\RFAK\nm\game04(www.songs.pk).mp3 Yahaan Roadies 8 MyDiddle.com Airport MyDiddle.com Roadies 8 MyDiddle.com MyDiddle.com 3758166 232 12/12/2010 10:29 AM 11/16/2012 9:13 PM 128 44100 MPEG aud io file MyDiddle.com D:\Music \mm\MTV Roadies 8 Yahaan (Theme Song).mp3 Deva Shree Ganesha www.Songs.PK Ajay Gogavale Music: AjayAtul | Lyric s: Amitabh Bhattacharya Agneepath www.Songs.PK Bollywood Music 7287918 356 6 2011 4/17/2012 8:40 PM 11/16/20 12 9:13 PM 161 44100 MPEG audio file www.Songs.PK D:\Music\agneepath\agneepath06(www.songs.pk).mp3 That's My Name -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2015 Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Shabazz, Sultana Aaliuah, "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3607 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz entitled "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Education. Barbara J. Thayer-Bacon, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Harry Dahms, Rebecca Klenk, Lois Presser Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Conference on "Towards New Visions: Women in Films, Media

Towards New Visions: Women in Films, Media and Beyond Virtual Conference, 11-12 March 2021 http://uoguel.ph/circleconference01 Organizers Aysha Iqbal Viswamohan, Indian Institute of Technology, Madras Sharada Srinivasan, University of Guelph Host Canada India Research Centre for Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) Sponsor Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute’s Golden Jubilee Conference and Lecture Series Grant (GJCLSG) Day 1, 11 March 2021 7: 00p.m.-12:30a.m. IST/ 8:30a.m.-2:00p.m. EST Opening session 7:00-7:45p.m. Welcome: Dr. Sharada Srinivasan, Director, CIRCLE Introduction to the conference: Dr. Aysha Iqbal Viswamohan Opening remarks: Dr. Charlotte Yates, President & Vice-Chancellor, University of Guelph Opening remarks: Dr. Prachi Kaul, Director, SICI Plenary Session-1 8:00-9:00p.m. Parallel Session-1 9:55- 11:55p.m. Women’s Success Stories in Films and Media Women’s Empowerment on Screen, and New Media: Feminist Screen Chair: Aysha Iqbal Viswamohan Cultures in the Age of Digital Technologies Aswiny Iyer Tiwari Chair: Madhuja Mukherjee Pooja Ladha Surti 1. Collaborative Praxis: Feminisms and Empowerment in Contemporary Popular Bengali Cinema, Smita Bannerjee 2. Indian Women Rising: Female Star Portfolios in the Era of Digital Platforms, Akriti Rastogi 3. No Country for Aunties: A Feminist Inquiry into Intersectional Self- Fashioning in Popular Visual Culture, Shromona Das 4. Rethinking Stereotypes: Embodiment of the Female Aging Self in Select Bengali films, Debashrita Dey 5. Exonerating Disruptive Mothers and Rebellious Daughters: New Discourses of Femininity in Shakuntala Devi and Tribhanga-Tedhi Medhi Crazy, Sanchari Basu Chaudhury Plenary Session-2 9:10-9:45p.m. -

Veer–Zaara Regie: Yash Chopra

Veer–Zaara Regie: Yash Chopra Land: Indien 2004. Produktion: Yash Raj Films (Mumbai). Regie: Yash Chopra. Buch: Aditya Chopra. Regie Actionszenen: Allan Amin. Kamera: Anil Mehta. Ton: Anuj Mathur. Musik: Madan Mohan. Neueinspielung: Sanjeev Kohli. Arrangements: R.S. Mani. Liedtexte: Javed Akhtar. Sänger: Lata Mangeshkar, Udit Narayan, Sonu Nigam, Roop Kumar Rathod, Gurdas Mann, Ahmed Hussain, Mohammed Hussain, Mohammed Vakil, Javed Hussain, Pritha Majumder. Ausstattung: Sharmishta Roy. Choreographie: Saroj Khan, Vaibhavi Merchant. Kostüme: Manish Malhotra. Beratung (Drehbuch & Ausstattung): Nasreen Rehman. Schnitt: Ritesh Soni. Produzenten: Yash Chopra, Aditya Chopra. Co-Produzenten: Pamela Chopra, Uday Chopra, Payal Chopra. Aufnahmeleitung: Sanjay Shivalkar, Padam Bhushan. Darsteller: Shahrukh Khan (Veer Pratap Singh), Rani Mukerji (Saamiya Siddiqui), Preity Zinta (Zaara), Kirron Kher, Divya Dutta, Boman Irani, Anupam Kher, Amitabh Bachchan, Hema Malini, Manoj Bajpai, Zohra Segal (Bebe), S.M. Zaheer (Justice Qureshi), Tom Alter (Dr. Yusuf), Gurdas Mann (als er selbst), Arun Bali (Abdul Mallik Shirazi, Razas Vater), Akhilendra Mishra (Gefängniswärter Majid Khan), Rushad Rana (Saahil), Vinod Negi (Ranjeet), Balwant Bansal (Qazi), Rajesh Jolly (Priester), Anup Kanwal Singh (Sänger), Kanwar Jagdish (Glatzkopf im Bus), Dev K. Kantawalla (Munir), Vicky Ahuja (Vernehmungsbeamtin), Ranjeev Verma (Vernehmungsbeamter), Jas Keerat (Junger Cricket-Spieler), Sanjay Singh Bhadli (Bauer), Kulbir Baderson (Töpferin), Shivaya Singh (Kamli), Huzeifa Gadiwalla