American Kathaks: Embodying Memory and Tradition in New Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Siddheshwari Devi Final Edit Rev 1

Siddheshwari Devi – The Queen of Thumri1 by Aditi Desai Kashi, Benares or Varanasi; the ancient spiritual centre of Hindustan, famous for its Ganga, its temples and ghats, pandits and pandas, had another more sensual side in its graceful yet throbbing sub-culture of music and dance. There was a time when for every devotee going to a temple to propitiate the gods there was another who, chewing his delicately flavoured paan, 1 Edited, updated and rewritten version based on: Original article written by Aditi Desai for The India Magazine, Aug. 1981, No. 9 would be strolling towards some singer’s or dancer’s house. In the Benares sunset, the sound of temple bells intermingled with the soul stirring sounds of a bhajan, a thumri, a kajri, a chaiti, a hori. And accompanying these were the melodious sounds of the sarangi or flute and the ghunghroos on the beat of the tabla that quickened the heartbeat. So great was the city’s preoccupation with music, that a distinctive style of classical music, rooted in the local folk culture, emerged and was embodied in the Benaras Gharana ( school or a distinctive style of music originating in a family tradition or lineage that can be traced to an instructor or region). A few miles from Benares, there is a village called Torvan, which appears to be like any other Thakur Brahmin village of that region. But there is a difference. This village had a few families belonging to the Gandharva Jati, a group whose traditional occupation was music and its allied arts. Amongst Gandharvas, it was the men who went out to perform while the women stayed behind. -

Indian Classical Dance Is a Relatively New Umbrella Term for Various Codified Art Forms Rooted in Natya, the Sacred Hindu Musica

CLASSICAL AND FOLK DANCES IN INDIAN CULTURE Palkalai Chemmal Dr ANANDA BALAYOGI BHAVANANI Chairman: Yoganjali Natyalayam, Pondicherry. INTRODUCTION: Dance in India comprises the varied styles of dances and as with other aspects of Indian culture, different forms of dances originated in different parts of India, developed according to the local traditions and also imbibed elements from other parts of the country. These dance forms emerged from Indian traditions, epics and mythology. Sangeet Natak Akademi, the national academy for performing arts, recognizes eight distinctive traditional dances as Indian classical dances, which might have origin in religious activities of distant past. These are: Bharatanatyam- Tamil Nadu Kathak- Uttar Pradesh Kathakali- Kerala Kuchipudi- Andhra Pradesh Manipuri-Manipur Mohiniyattam-Kerala Odissi-Odisha Sattriya-Assam Folk dances are numerous in number and style, and vary according to the local tradition of the respective state, ethnic or geographic regions. Contemporary dances include refined and experimental fusions of classical, folk and Western forms. Dancing traditions of India have influence not only over the dances in the whole of South Asia, but on the dancing forms of South East Asia as well. In modern times, the presentation of Indian dance styles in films (Bollywood dancing) has exposed the range of dance in India to a global audience. In ancient India, dance was usually a functional activity dedicated to worship, entertainment or leisure. Dancers usually performed in temples, on festive occasions and seasonal harvests. Dance was performed on a regular basis before deities as a form of worship. Even in modern India, deities are invoked through religious folk dance forms from ancient times. -

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

Rabindra Sangeet

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION NET BUREAU Subject: MUSIC Code No.: 16 SYLLABUS Hindustani (Vocal, Instrumental & Musicology), Karnataka, Percussion and Rabindra Sangeet Note:- Unit-I, II, III & IV are common to all in music Unit-V to X are subject specific in music www.careerindia.com -1- Unit-I Technical Terms: Sangeet, Nada: ahata & anahata , Shruti & its five jaties, Seven Vedic Swaras, Seven Swaras used in Gandharva, Suddha & Vikrit Swara, Vadi- Samvadi, Anuvadi-Vivadi, Saptak, Aroha, Avaroha, Pakad / vishesa sanchara, Purvanga, Uttaranga, Audava, Shadava, Sampoorna, Varna, Alankara, Alapa, Tana, Gamaka, Alpatva-Bahutva, Graha, Ansha, Nyasa, Apanyas, Avirbhav,Tirobhava, Geeta; Gandharva, Gana, Marga Sangeeta, Deshi Sangeeta, Kutapa, Vrinda, Vaggeyakara Mela, Thata, Raga, Upanga ,Bhashanga ,Meend, Khatka, Murki, Soot, Gat, Jod, Jhala, Ghaseet, Baj, Harmony and Melody, Tala, laya and different layakari, common talas in Hindustani music, Sapta Talas and 35 Talas, Taladasa pranas, Yati, Theka, Matra, Vibhag, Tali, Khali, Quida, Peshkar, Uthaan, Gat, Paran, Rela, Tihai, Chakradar, Laggi, Ladi, Marga-Deshi Tala, Avartana, Sama, Vishama, Atita, Anagata, Dasvidha Gamakas, Panchdasa Gamakas ,Katapayadi scheme, Names of 12 Chakras, Twelve Swarasthanas, Niraval, Sangati, Mudra, Shadangas , Alapana, Tanam, Kaku, Akarmatrik notations. Unit-II Folk Music Origin, evolution and classification of Indian folk song / music. Characteristics of folk music. Detailed study of folk music, folk instruments and performers of various regions in India. Ragas and Talas used in folk music Folk fairs & festivals in India. www.careerindia.com -2- Unit-III Rasa and Aesthetics: Rasa, Principles of Rasa according to Bharata and others. Rasa nishpatti and its application to Indian Classical Music. Bhava and Rasa Rasa in relation to swara, laya, tala, chhanda and lyrics. -

Godrej Consumer Products Limited

GODREJ CONSUMER PRODUCTS LIMITED List of shareholders in respect of whom dividend for the last seven consective years remains unpaid/unclaimed The Unclaimed Dividend amounts below for each shareholder is the sum of all Unclaimed Dividends for the period Nov 2009 to May 2016 of the respective shareholder. The equity shares held by each shareholder is as on Nov 11, 2016 Sr.No Folio Name of the Shareholder Address Number of Equity Total Dividend Amount shares due for remaining unclaimed (Rs.) transfer to IEPF 1 0024910 ROOP KISHORE SHAKERVA I R CONSTRUCTION CO LTD P O BOX # 3766 DAMMAM SAUDI ARABIA 180 6,120.00 2 0025470 JANAKIRAMA RAMAMURTHY KASSEMDARWISHFAKROO & SONS PO BOX 3898 DOHA QATAR 240 8,160.00 3 0025472 NARESH KUMAR MAHAJAN 176 HIGHLAND MEADOW CIRCLE COPPELL TEXAS U S A 240 8,160.00 4 0025645 KAPUR CHAND GUPTA C/O PT SOUTH PAC IFIC VISCOSE PB 11 PURWAKARTA WEST JAWA INDONESIA 360 12,240.00 5 0025925 JAGDISHCHANDRA SHUKLA C/O GEN ELECTRONICS & TDG CO PO BOX 4092 RUWI SULTANATE OF OMAN 240 8,160.00 6 0027324 HARISH KUMAR ARORA 24 STONEMOUNT TRAIL BRAMPTON ONTARIO CANADA L6R OR1 360 12,240.00 7 0028652 SANJAY VARNE SSB TOYOTA DIVI PO BOX 6168 RUWI AUDIT DEPT MUSCAT S OF OMAN 60 2,040.00 8 0028930 MOHAMMED HUSSAIN P A LEBANESE DAIRY COMPANY POST BOX NO 1079 AJMAN U A E 120 4,080.00 9 K006217 K C SAMUEL P O BOX 1956 AL JUBAIL 31951 KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA 180 6,120.00 10 0001965 NIRMAL KUMAR JAIN DEP OF REVENUE [INCOMETAX] OFFICE OF THE TAX RECOVERY OFFICER 4 15/295A VAIBHAV 120 4,080.00 BHAWAN CIVIL LINES KANPUR 11 0005572 PRAVEEN -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Reconstructing the Indian Filmography

ASHISH RAJADHYAKSHA Reconstructing The Indian Filmography Sitara Devi and the Indian filmographer A n apocryphal story has V.A.K. Ranga Rao, the irascible collector of music and authority on South Indian cinema, offering an open challenge. It seems he saw Mother India on his television one night and was taken aback to see Sitara Devi’s name in the acting credits. The open challenge was to anyone who could spot Sitara Devi anywhere in the film. And, he asked, if she was not in the film, to answer two questions. First, what happened? Was something filmed with her and cut out? If so, when was this cut out? Almost more important: what to do with Sitara Devi’s filmography? Should Mother India feature in that or not? Such a problem would cut deep among what I want to call the classic years of the Indian filmographers. The Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema decided to include Sitara Devi’s name in its credits, mainly because its own key source for Hindi credits before 1970 was Firoze Rangoonwala’s iconic Indian Filmography, Silent and Hindi Film: 1897-1969, published in 1970 and Har Mandir Singh ‘Hamraaz’s somewhat different, equally legendary Hindi Film Geet Kosh which came out with the first edition of its 1951-60 listings in 1980. The Singh Geet Kosh tradition would provide bulwark support both on JOURNAL OF THE MOVING IMAGE 13 its own but also through a series of other Geet Koshes by Harish Raghuvanshi on Gujarati, Murladhar Soni on Rajasthani and many others. Like Ranga Rao, Singh and the other Geet Kosh editors have had his own variations of the Sitara Devi problem: his focus was on songs, and he was coming across major discrepancies between film titles, their publicity material and record listings. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

All in One Gs 06 फेब्रुअरी 2019

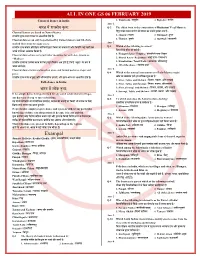

ALL IN ONE GS 06 FEBRUARY 2019 Classical Dance in India: 3. Yajurveda / यजुर्ेद 4. Rigveda / ऋग्र्ेद Ans- 2 भारत मᴂ शास्त्रीय न配ृ य: Q-2 The oldest form of the composition of Hindustani Vocal Music is: Classical Dances are based on Natya Shastra. सहंदुस्तानी गायन संगीत की रचना का सबसे पुराना 셂प है: शास्त्रीय नृ配य नाट्य शास्त्र पर आधाररत होते हℂ। 1. Ghazal / ग़ज़ल 2. Dhrupad / ध्रुपद Classical dances can only be performed by trained dancers and who have 3. Thumri / ठुमरी 4. Qawwali / कव्र्ाली studied their form for many years. Ans- 2 शास्त्रीय नृ配य के वल प्रशशशित नततशकयⴂ द्वारा शकया जा सकता है और शजन्हⴂने कई वर्षⴂ तक Q-3 Which of the following is correct? अपने 셁पⴂ का अध्ययन शकया है। सन륍न में से कौन सा सही है? Classical dances have very particular meanings for each step, known as 1. Hojagiri dance- Tripura / होजासगरी नृ配य- सिपुरा "Mudras". 2. Bhavai dance- Rajasthan / भर्ई नृ配य- राजस्थान शास्त्रीय नृ配यⴂ के प्र配येक चरण के शलए बहुत शवशेर्ष अर्त होते हℂ, शजन्हᴂ "मुद्रा" के 셂प मᴂ 3. Karakattam- Tamil Nadu / करकटम- तसमलनाडु जाना जाता है। 4. All of the above / उपरोक्त सभी Classical dance forms are based on grace and formal gestures, steps, and Ans- 4 poses. Q-4 Which of the musical instruments is of Indo-Islamic origin? शास्त्रीय नृ配य 셂पⴂ अनुग्रह और औपचाररक इशारⴂ, और हाव-भाव पर आधाररत होते हℂ। कौन सा र्ाद्ययंि इडं ो-इस्लासमक मूल का है? 1. -

Classical Dances Have Drawn Sustenance

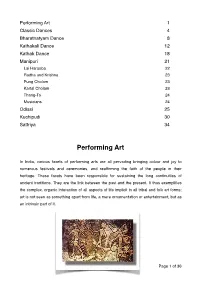

Performing Art 1 Classic Dances 4 Bharatnatyam Dance 8 Kathakali Dance 12 Kathak Dance 18 Manipuri 21 Lai Haraoba 22 Radha and Krishna 23 Pung Cholam 23 Kartal Cholam 23 Thang-Ta 24 Musicians 24 Odissi 25 Kuchipudi 30 Sattriya 34 Performing Art In India, various facets of performing arts are all pervading bringing colour and joy to numerous festivals and ceremonies, and reaffirming the faith of the people in their heritage. These facets have been responsible for sustaining the long continuities of ancient traditions. They are the link between the past and the present. It thus exemplifies the complex, organic interaction of all aspects of life implicit in all tribal and folk art forms; art is not seen as something apart from life, a mere ornamentation or entertainment, but as an intrinsic part of it. Page !1 of !36 Pre-historic Cave painting, Bhimbetka, Madhya Pradesh Under the patronage of Kings and rulers, skilled artisans and entertainers were encouraged to specialize and to refine their skills to greater levels of perfection and sophistication. Gradually, the classical forms of Art evolved for the glory of temple and palace, reaching their zenith around India around 2nd C.E. onwards and under the powerful Gupta empire, when canons of perfection were laid down in detailed treatise - the Natyashastra and the Kamasutra - which are still followed to this day. Through the ages, rival kings and nawabs vied with each other to attract the most renowned artists and performers to their courts. While the classical arts thus became distinct from their folk roots, they were never totally alienated from them, even today there continues a mutually enriching dialogue between tribal and folk forms on the one hand, and classical art on the other; the latter continues to be invigorated by fresh folk forms, while providing them with new thematic content in return. -

Punjab Current Affairs-3

Punjab Current Affairs 9 Which country has been invited as the partner country for this year's 'Gita Jayanti Mahotsav', scheduled to be held at Kurukshetra from December 3 to 8? 1. Bhutan 2. Nepal 3. Myanmar 4. Maldives Ans. 2 With which, NITI Aayog has partnered to promote women entrepreneurs? 1. Google 2. Tik Tok 3. Facebook 4. WhatsApp Ans. 4 Which State has topped in solar rooftop installations? 1. Madhya Pradesh 2. Gujarat 3. Kerala 4. Karnataka Ans. 2 According to 'QS Best Student Cities Ranking', Which city has been named as the world's best city for students for the second consecutive year? 1. Vienna 2. Mumbai 3. London 4. Bangalore Ans. 3 Who took oath as the Governor of Madhya Pradesh? 1. P Gopi Krishna 2. M. Mukesh Goud 3. Lalji Tandon 4. Ramesh Bais Ans. 3 Who appointed as the chairman of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC)? 1. Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury 2. Arjun Munda 3. Om Birla 4. Mahendra Nath Pandey Ans. 1 Which State Government has signed an MoU with Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre (VSSC) to develop Space Park? 1. Kerala 2. Maharashtra 3. Andhra Pradesh 4. Telangana Ans.1 Who has been conferred with the M S Swamianathan Award for Environment Protection? 1. Kenneth M Quinn 2. Kristalina Georgieva 3. David-Maria Sassoli 4. Charles Michel Ans.1 Which Sports Brand has tied up with India‟s woman athlete Dute Chand? 1. Nike 2. Sketcher 3. Adidas 4. Puma Ans.4 In which city, Prime Minister of Nepal KP Sharma Oli inaugurated India-Nepal Logistics Summit? 1.