Formulas and the Building Blocks of Ṭhumrī Style—A Study in “Improvised” Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siddheshwari Devi Final Edit Rev 1

Siddheshwari Devi – The Queen of Thumri1 by Aditi Desai Kashi, Benares or Varanasi; the ancient spiritual centre of Hindustan, famous for its Ganga, its temples and ghats, pandits and pandas, had another more sensual side in its graceful yet throbbing sub-culture of music and dance. There was a time when for every devotee going to a temple to propitiate the gods there was another who, chewing his delicately flavoured paan, 1 Edited, updated and rewritten version based on: Original article written by Aditi Desai for The India Magazine, Aug. 1981, No. 9 would be strolling towards some singer’s or dancer’s house. In the Benares sunset, the sound of temple bells intermingled with the soul stirring sounds of a bhajan, a thumri, a kajri, a chaiti, a hori. And accompanying these were the melodious sounds of the sarangi or flute and the ghunghroos on the beat of the tabla that quickened the heartbeat. So great was the city’s preoccupation with music, that a distinctive style of classical music, rooted in the local folk culture, emerged and was embodied in the Benaras Gharana ( school or a distinctive style of music originating in a family tradition or lineage that can be traced to an instructor or region). A few miles from Benares, there is a village called Torvan, which appears to be like any other Thakur Brahmin village of that region. But there is a difference. This village had a few families belonging to the Gandharva Jati, a group whose traditional occupation was music and its allied arts. Amongst Gandharvas, it was the men who went out to perform while the women stayed behind. -

Music Initiative Jka Peer - Reviewed Journal of Music

VOL. 01 NO. 01 APRIL 2018 MUSIC INITIATIVE JKA PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC PUBLISHED,PRINTED & OWNED BY HIGHER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, J&K CIVIL SECRETARIAT, JAMMU/SRINAGAR,J&K CONTACT NO.S: 01912542880,01942506062 www.jkhighereducation.nic.in EDITOR DR. ASGAR HASSAN SAMOON (IAS) PRINCIPAL SECRETARY HIGHER EDUCATION GOVT. OF JAMMU & KASHMIR YOOR HIGHER EDUCATION,J&K NOT FOR SALE COVER DESIGN: NAUSHAD H GA JK MUSIC INITIATIVE A PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC INSTRUCTION TO CONTRIBUTORS A soft copy of the manuscript should be submitted to the Editor of the journal in Microsoft Word le format. All the manuscripts will be blindly reviewed and published after referee's comments and nally after Editor's acceptance. To avoid delay in publication process, the papers will not be sent back to the corresponding author for proof reading. It is therefore the responsibility of the authors to send good quality papers in strict compliance with the journal guidelines. JK Music Initiative is a quarterly publication of MANUSCRIPT GUIDELINES Higher Education Department, Authors preparing submissions are asked to read and follow these guidelines strictly: Govt. of Jammu and Kashmir (JKHED). Length All manuscripts published herein represent Research papers should be between 3000- 6000 words long including notes, bibliography and captions to the opinion of the authors and do not reect the ofcial policy illustrations. Manuscripts must be typed in double space throughout including abstract, text, references, tables, and gures. of JKHED or institution with which the authors are afliated unless this is clearly specied. Individual authors Format are responsible for the originality and genuineness of the work Documents should be produced in MS Word, using a single font for text and headings, left hand justication only and no embedded formatting of capitals, spacing etc. -

Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free Static GK E-Book

oliveboard FREE eBooks FAMOUS INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSICIANS & VOCALISTS For All Banking and Government Exams Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Current Affairs and General Awareness section is one of the most important and high scoring sections of any competitive exam like SBI PO, SSC-CGL, IBPS Clerk, IBPS SO, etc. Therefore, we regularly provide you with Free Static GK and Current Affairs related E-books for your preparation. In this section, questions related to Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists have been asked. Hence it becomes very important for all the candidates to be aware about all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. In all the Bank and Government exams, every mark counts and even 1 mark can be the difference between success and failure. Therefore, to help you get these important marks we have created a Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. The list of all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists is given in the following pages of this Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Sample Questions - Q. Ustad Allah Rakha played which of the following Musical Instrument? (a) Sitar (b) Sarod (c) Surbahar (d) Tabla Answer: Option D – Tabla Q. L. Subramaniam is famous for playing _________. (a) Saxophone (b) Violin (c) Mridangam (d) Flute Answer: Option B – Violin Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Name Instrument Music Style Hindustani -

And Joydeep Ghosh (Sarod)

The Asian Indian Classical Music Society 51491 Norwich Drive Granger, IN 46530 Concert Announcement Vidushi Mita Nag (sitar) Pandit Joydeep Ghosh (sarod) with Pandit Subhen Chatterjee (Tabla) April 26, 2016, Tuesday, 7.00PM At: the Andrews Auditorium, Geddes Hall University of Notre Dame Cosponsored with the Liu Institute of Asia and Asian Studies Tickets available at gate. General Admission: $10, AICMS Members and ND/SMC faculty: $5, Students: FREE Mita Nag, daughter of the veteran sitarist, Pandit Manilal Nag and granddaughter of Sangeet Acharya Gokul Nag, belongs to the Vishnupur Gharana of Bengal, a school of music that is nearly 300 years old and which is known for its dhrupad style of playing. She was initiated into music at the age of four, and studied with her mother, grandfather and father. She appeared for her debut performance at the age of ten, when she also won the Government of India’s Junior National Talent Search Award. She has given many concert performances, both alone and with her father, in cities in the US, Canada, Japan and Europe as well as in India. Joydeep Ghosh is hailed as one of India’s leading sarod, surshringar and Mohanveena artists. He started his sarod training at the age of five, and has studied with the great masters the late Sangeetacharya Anil Roychoudhury , late Sangeetacharya Radhika Mohan Moitra and Padmabhusan Acharya Buddhadev Dasgupta all of the Shahajahanpur Gharana. He has won numerous awards and fellowships, including those from the Government of India, the title of “Suramani” from the Sur Singar Samsad (Mumbai) and “Swarshree” from Swarankur (Mumbai). -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-19605-6 — Boundaries of Belonging Sarah Ansari , William Gould Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-19605-6 — Boundaries of Belonging Sarah Ansari , William Gould Index More Information Index 18th Amendment, 280 All-India Muslim Ladies’ Conference, 183 All-India Radio, 159 Aam Aadmi (Ordinary Man) Party, 273 All-India Refugee Association, 87–88 abducted women, 1–2, 12, 202, 204, 206 All-India Refugee Conference, 88 abwab, 251 All-India Save the Children Committee, Acid Control and Acid Crime Prevention 200–201 Act, 2011, 279 All-India Scheduled Castes Federation, 241 Adityanath, Yogi, 281 All-India Women’s Conference, 183–185, adivasis, 9, 200, 239, 261, 263, 266–267, 190–191, 193–202 286 All-India Women’s Food Council, 128 Administration of Evacuee Property Act, All-Pakistan Barbers’ Association, 120 1950, 93 All-Pakistan Confederation of Labour, 256 Administration of Evacuee Property All-Pakistan Joint Refugees Council, 78 Amendment Bill, 1952, 93 All-Pakistan Minorities Alliance, 269 Administration of Evacuee Property Bill, All-Pakistan Women’s Association 1950, 230 (APWA), 121, 202–203, 208–210, administrative officers, 47, 49–50, 69, 101, 212, 214, 218, 276 122, 173, 176, 196, 237, 252 Alwa, Arshia, 215 suspicions surrounding, 99–101 Ambedkar, B.R., 159, 185, 198, 240, 246, affirmative action, 265 257, 262, 267 Aga Khan, 212 Anandpur Sahib, 1–2 Agra, 128, 187, 233 Andhra Pradesh, 161, 195 Ahmad, Iqbal, 233 Anjuman Muhajir Khawateen, 218 Ahmad, Maulana Bashir, 233 Anjuman-i Khawateen-i Islam, 183 Ahmadis, 210, 268 Anjuman-i Tahafuuz Huqooq-i Niswan, Ahmed, Begum Anwar Ghulam, 212–213, 216 215, 220 -

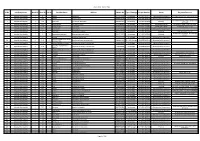

Teachers of Private Colleges (Under Section 17 – Elected Members (6) of the Kerala University Act, 1974)

1 Price Rs. 100/- per copy UNIVERSITY OF KERALA Election to the Senate from the Teachers of Private Colleges (Under Section 17 – Elected Members (6) of the Kerala University Act, 1974) ELECTORAL ROLL OF TEACHERS OF PRIVATE COLLEGES-2018 ROLL No. Name Designation College 1. Dr.Caroline Beena Mendez DDO All Saints’ College. 2. Sonya J Nair Assistant Professor ,, 3. Kukku Xavier Assistant Professor ,, 4. Dr.Liji Varghese Assistant Professor ,, 5. Dr.Sr.Pascoela Adelrich Assistant Professor ,, D’Souza 6. Dr.Rajsree M.S Assistant Professor ,, 7. Sapna Srinivas Assistant Professor ,, 8. Simna S Stephen Assistant Professor ,, 9. Nishel Prem Elias Assistant Professor ,, 10. Diana V Prakash Assistant Professor ,, 11. Dr.Kavitha .N Assistant Professor ,, 12. Joveeta Justin Assistant Professor ,, 13. Celina James Assistant Professor ,, 14. Dr.C.Udayakala Assistant Professor ,, 15. Parvathy Menon Assistant Professor ,, 16. Vijayakumari K Assistant Professor ,, 17. Dr.Sreelekha Nair Associate professor ,, 18. Dr.Reshmi.R.Prasad Associate professor ,, 19. Lissy Bennet Assistant Professor ,, 20. Shirly Joseph Associate professor All Saints’ College. 21. Sebina Mathew C Assistant Professor ,, 22. Renjini Raveendran P Assistant Professor ,, 23. Vidhya T.R Assistant Professor ,, 24. Dr.Deepa M Associate professor ,, 25. Dr.Anjana P.S Assistant Professor ,, 2 26. Dr.Veena Suresh Babu Assistant Professor ,, 27. Dr.Sunitha Kurur Assistant Professor ,, 28. Dr.Sindhu Yesodharan Assistant Professor ,, 29. Dr.Siji V.L Assistant Professor ,, 30. Dr.Beena Kumari K.S Assistant Professor ,, 31. Dr.Nisha K.K Assistant Professor ,, 32. Dr.Sr.Shaina T J Assistant Professor ,, 33. Dr.Dhanalekshmi.T.G Assistant Professor ,, 34. Divya Grace Dilip Assistant Professor ,, 35. -

This Article Has Been Made Available to SAWF by Dr. Veena Nayak. Dr. Nayak Has Translated It from the Original Marathi Article Written by Ramkrishna Baakre

This article has been made available to SAWF by Dr. Veena Nayak. Dr. Nayak has translated it from the original Marathi article written by Ramkrishna Baakre. From: Veena Nayak Subject: Dr. Vasantrao Deshpande - Part Two (Long!) Newsgroups: rec.music.indian.classical, rec.music.indian.misc Date: 2000/03/12 Presenting the second in a three-part series on this vocalist par excellence. It has been translated from a Marathi article by Ramkrishna Baakre. Baakre is also the author of 'Buzurg', a compilation of sketches of some of the grand old masters of music. In Part One, we got a glimpse of Vasantrao's childhood years and his early musical training. The article below takes up from the point where the first one ended (although there is some overlap). It discusses his influences and associations, his musical career and more importantly, reveals the generous and graceful spirit that lay behind the talent. The original article is rather desultory. I have, therefore, taken editorial liberties in the translation and rearranged some parts to smoothen the flow of ideas. I am very grateful to Aruna Donde and Ajay Nerurkar for their invaluable suggestions and corrections. Veena THE MUSICAL 'BRAHMAKAMAL' - Ramkrishna Baakre (translated by Dr. Veena Nayak) It was 1941. Despite the onset of November, winter had not made even a passing visit to Pune. In fact, during the evenings, one got the impression of a lazy October still lingering around. Pune has been described in many ways by many people, but to me it is the city of people with the habit of going for strolls in the morning and evening. -

Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks

Flood 2019 - Vythiri Taluk Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks 1 Kalpetta Municipality 1 0 kamala neduelam 8157916492 No damage 31219021600235 Approved(Disbursement) RATION CARD DETAILS NOT AVAILABLE 2 Kalpetta Municipality 1 135 sabitha strange nivas 8086336019 No damage 31219021600240 Disbursed to Government 3 Kalpetta Municipality 1 138 manjusha sukrutham nedunilam 7902821756 No damage 31219021600076 Pending THE ADHAR CARD UPDATED ANOTHER ACCOUNT 4 Kalpetta Municipality 1 144 devi krishnan kottachira colony 9526684873 No damage 31219021600129 Verified(LRC Office) NO BRANCH NAME AND IFSC CODE 5 Kalpetta Municipality 1 149 janakiyamma kozhatatta 9495478641 >75% Damage 31219021600080 Verified(LRC Office) PASSBOOK IS NO CLEAR 6 Kalpetta Municipality 1 151 anandavalli kozhathatta 9656336368 No damage 31219021600061 Disbursed to Government 7 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 chandran nedunilam st colony 9747347814 No damage 31219021600190 Withheld PASSBOOK NOT CLEAR 8 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 3 sangeetha pradeepan rajasree gives nedunelam 9656256950 No damage 31219021600090 Withheld No damage type details and damage photos 9 Kalpetta Municipality 1 161 shylaja sasneham nedunilam 9349625411 No damage 31219021600074 Disbursed to Government Manjusha padikkandi house 10 Kalpetta Municipality 1 172 3 maniyancode padikkandi house maniyancode 9656467963 16 - 29% Damage 31219021600072 Disbursed to Government 11 Kalpetta Municipality 1 175 vinod madakkunnu colony -

The Melodic Power of Thumri by : INVC Team Published on : 16 Sep, 2018 05:32 AM IST

The melodic power of thumri By : INVC Team Published On : 16 Sep, 2018 05:32 AM IST INVC NEWS New Delhi , Delhi government’s Sahitya Kala Parishad kick started their eighth edition of Thumri Festival- a celebration of light classical music, on 14th September 2018 (Friday) at Kamani Auditorium. The 3 day musical event was inaugurated by the chief guest Sh. Rajendra Pal Gautam, Hon’ble Minister for Social Welfare, Govt. Of NCT of Delhi. The evening began with the performance of critically acclaimed Indian classical singer Padmaja Chakraborty, who sang Khamaj Thumri in Jat taal, Tappa in Raga Kafi and Kajri in Raag Mishra Pilu in Keherwa taal. The second performance was by the renowned vocalist and doyen of Kirana Gharana - Sri Jayateerth Mevundi. The classical singer, known for the ease and felicity of his singing style, mesmerized the audience with Raag Tilang Thumri, kafi Thumri, Jogiya Thumri, and Raag Pahadi in different raag and tal. The evening was culminated with a power packed performance by Shubha Mudgal who performed on Bol Banau Thumri and Bandish ki Thumri in which she sang rare types of Thumri for the audience. This musical fare is designed to showcase veteran Thumri singers along with the upcoming young talents who will share the space and light up the evening with their performances. About thumri : Thumri is a beautiful blend of Hindustani classical music with traits of folk literature. Thumri holds a history of over 500 years in Hindustani Classical music. Thumri used to be sung in the royal kingdoms and palaces and its background originates from Varanasi, Gwalior and Awadh were they used to be Thumri vocalists in the royal courts. -

Teachers Day Program Details 2018 V11

CMANA 4. Time: 12:00 PM to 12:20 PM in association with GCD 2017 Winner The Sringeri Vidya Bharati Foundation, USA Keshav Muralidharan 19th May 2018 from 10:30 AM Onwards (Vocal) Location The Auditorium, Sringeri Vidya Bharati Foundation, 327,Cays Road, Stroudsburg PA 18360 Break Time: 12:30 PM to 01:15 PM 1. Time: 10:30 AM to 10:50 AM GCD 2017 Winner 5. Time: 01:20 PM to 01:40 PM Neharika Murthy GCD 2016 Winner of Padma Srinivasan Prize (Vocal) Srinath Peraganur ((violin)) 2. Time: 11:00 AM to 11:20 AM Local Teacher Group Participation 6. Time: 01:50 PM to 02:10 PM Teacher Name: Teacher Name: Local Teacher Group Participation Bhavani Prakash Prakash Rao Teacher Name: Manjula Ramachandran Participants Participants Krishna Palya Ananth Rayar Sabarinath Manjula Ramachandran Hemant Gosukonda Ramachandran 3. Time: 11:30 AM to 11:50 AM (Veena) (Vocal) (Mridangam) Local Teacher Group Participation Teacher Name: 7. Time: 02:15 PM to 03:00 PM Srividhya Sairam CMANA HONY PATRON PADMA SRINIVASAN AWARD WINNER IN INSTRUMENTAL CATEGORY ( KRITI,ALAPANA AND SWARAM) IN 2017 Participants Vishal Sowmyan Sabari Ramachandran (Violin) (Mridangam) Sanjana Venkatesh Sowmya Venkatesh www.cmana.org 02 8. Time: 03:10 PM to 03:30 PM GCD 2017 Winner Shardul Krishnakumar T S Nandakumar Shri T.S. Nandakumar, an Top grade artist of the All India Radio, hails 9. Time: 03:40 PM to 04:00 PM from the family of the renowned Nadaswaram exponents, Ambalapuzha Brothers of Kerala. He underwent training in percussion Local Teacher Group Participation under Shri Kaithavana Madhavdas in the Gurukulam tradition.