Cultural Geography of Kathak Dance: Streams of Tradition and Global Flows*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siddheshwari Devi Final Edit Rev 1

Siddheshwari Devi – The Queen of Thumri1 by Aditi Desai Kashi, Benares or Varanasi; the ancient spiritual centre of Hindustan, famous for its Ganga, its temples and ghats, pandits and pandas, had another more sensual side in its graceful yet throbbing sub-culture of music and dance. There was a time when for every devotee going to a temple to propitiate the gods there was another who, chewing his delicately flavoured paan, 1 Edited, updated and rewritten version based on: Original article written by Aditi Desai for The India Magazine, Aug. 1981, No. 9 would be strolling towards some singer’s or dancer’s house. In the Benares sunset, the sound of temple bells intermingled with the soul stirring sounds of a bhajan, a thumri, a kajri, a chaiti, a hori. And accompanying these were the melodious sounds of the sarangi or flute and the ghunghroos on the beat of the tabla that quickened the heartbeat. So great was the city’s preoccupation with music, that a distinctive style of classical music, rooted in the local folk culture, emerged and was embodied in the Benaras Gharana ( school or a distinctive style of music originating in a family tradition or lineage that can be traced to an instructor or region). A few miles from Benares, there is a village called Torvan, which appears to be like any other Thakur Brahmin village of that region. But there is a difference. This village had a few families belonging to the Gandharva Jati, a group whose traditional occupation was music and its allied arts. Amongst Gandharvas, it was the men who went out to perform while the women stayed behind. -

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

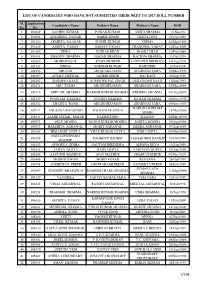

List of Candidates Who Have Not Submitted Their Neet Ug 2017 Roll Number

LIST OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE NOT SUBMITTED THEIR NEET UG 2017 ROLL NUMBER Sl. Application Candidate's Name Father's Name Mother's Name DOB No. No. 1 100249 SACHIN KUMAR PAWAN KUMAR ANITA SHARMA 15.Nov.93 2 100808 ANUSHEEL NAGAR OMBIR SINGH GEETA DEVI 07/Oct/1998 3 101222 AKSHITA DAAGAR SUSHIL KUMAR SEEMA 24/May/1999 4 101469 ANKITA YADAV SANJAY YADAV CHANCHAL YADAV 31/Dec/1999 5 101593 ZEWA NAWAB KHAN NOOR JAHAN 10/Feb/1999 6 101814 SHAGUN SHARMA GAGAN SHARMA RACHNA SHARMA 13/Oct/1998 7 102087 MOHD FAISAL SHAHABUDDIN JANNATUL FIRDOUS 14/Aug/1998 8 102121 SNEHA SOBODH KUMAR RAJENDRI 20/Jul/1998 9 102256 ABUZAR MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 25/Mar/1999 10 102397 ANJALI DESWAL JAGBIR SINGH RAJ RANI 05/Sep/1998 11 102402 RASMEET KAUR SURINDER PAL SINGH GURVINDER KAUR 11/Sep/1997 12 102474 ABU TALHA MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 25/Mar/1999 13 102515 SHIVANI SHARMA RAKESH KUMAR SHARMA KRISHNA SHARMA 01/Aug/2000 14 102529 POONAM SHARMA GOVIND SHARMA RAJESH SHARMA 04/Nov/1998 15 102532 SHAISTA BANO MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 09/Nov/1997 KARUNA KUMARI 16 102711 ANUSHKA RAJ SINGH RAJ KUMAR SINGH 12/Mar/2000 SINGH 17 102841 AAMIR SUHAIL MALIK NASIMUDDIN SHANNO 26/May/1996 18 102971 ABLE MOGHA MANOJ KUMAR MOGHA SARITA MOGHA 19/Aug/1998 19 103053 HARSHITA AGRAWAL MOHIT AGRAWAL MEERA AGRAWAL 07/Sep/1999 20 103245 HIMANSHI GUPTA VIJAY KUMAR GUPTA INDU GUPTA 09/May/2000 NGULLIENTHANG 21 103428 PAOKHUP HAOKIP VANKHOMOI HAOKIP 03/Oct/1998 HAOKIP 22 103433 APOORVA SINHA GAUTAM BIRENDRA ALPANA DEVA 12/Sep/1999 23 103518 TANYA GUPTA RAJIV GUPTA VANDANA GUPTA 29/Apr/1999 -

Willful Defaulters List

BANK OF MAHARASHTRA - WILLFUL DEFAULTERS LIST (SUIT FILED) AS OF 30.06.2021 cat Name of BKBR STATE SRN PRTY REGADDR OS AMT SUIT Other_Bk DIR1 DIN_DIR1 DIR2 DIN_DIR2 DIR3 DIN_DIR3 DIR4 DIN_DIR4 DIR5 DIN_DIR5 DIR6 DIN_DIR6 DIR7 DIN_DIR7 DIR8 DIN_DIR8 DIR9 DIN_DIR9 DIR10 DIN_DIR1 DIR11 DIN_DIR1 DIR12 DIN_DIR1 DIR13 DIN_DIR1 DIR14 DIN_DIR1 DIR15 DIN_DIR1 DIR16 DIN_DIR1 DIR17 DIN_DIR1 Remarks ego the Bank O Rs. In 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 ry lakhs Of Ba nk/ FI 2 BOM Ambad Maharashtr 1 DSL Enterprises F8-MIDC,Ambad,Dist.Nasik 173.86 Y Corporation Rajan 01530860 Mrs.Shobhana 01462223 Kamlesh K.R.Ghaisas A K Nasik a P.Ltd.(earlier Datar Bank,SBI,ICICI,I Bhalchandra Rajan Datar Morarji Exe.Director Shrivastav Switchge FCI,IIBI,IDB Datar M.D. (Nom IFCI) 2 BOM NMC Civil Maharashtr 2 Rellicon Plastics 50, Verma Lay out, Ambazari, Nagpur 45.97 Y Kishor Vasant Lines Nagpur a Dani 2 BOM Basvangudi Karnataka 3 Passidon Images No.10,Grape Garden,11th Cross,Maruti Indl. 26.01 Y Tamilnadu Sagar Rathod Aswin Banglore Estate,New Madiwala, Bangalore 560006 Mercantile Bank, Lakhanpal KSFC 2 BOM Ring Road, Gujarath 4 SALASAR RAYON PVT. 301, J K Towers,Ring Road, Surat 213.91 Y Ramesh Mrs.Renu Surat LTD . Radhyshyam Ramesh Jakhotia Jakhotia 2 BOM Ring Road, Gujarath 5 SAALASAR FIBERS PVT 301, J K Towers,Ring Road, Surat 150.22 Y Ramesh Mrs.Renu Surat LTD . Radheshyam Ramesh Jakhotia Jakhotia 2 BOM Ring Road, Gujarath 6 SUMEDH SYNTHETICS 301,J K Tower, Ring Road, Surat 170.76 Y Ramesh Mrs.Renu Surat PVT.LTD. -

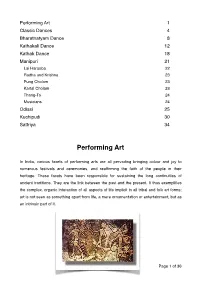

Classical Dances Have Drawn Sustenance

Performing Art 1 Classic Dances 4 Bharatnatyam Dance 8 Kathakali Dance 12 Kathak Dance 18 Manipuri 21 Lai Haraoba 22 Radha and Krishna 23 Pung Cholam 23 Kartal Cholam 23 Thang-Ta 24 Musicians 24 Odissi 25 Kuchipudi 30 Sattriya 34 Performing Art In India, various facets of performing arts are all pervading bringing colour and joy to numerous festivals and ceremonies, and reaffirming the faith of the people in their heritage. These facets have been responsible for sustaining the long continuities of ancient traditions. They are the link between the past and the present. It thus exemplifies the complex, organic interaction of all aspects of life implicit in all tribal and folk art forms; art is not seen as something apart from life, a mere ornamentation or entertainment, but as an intrinsic part of it. Page !1 of !36 Pre-historic Cave painting, Bhimbetka, Madhya Pradesh Under the patronage of Kings and rulers, skilled artisans and entertainers were encouraged to specialize and to refine their skills to greater levels of perfection and sophistication. Gradually, the classical forms of Art evolved for the glory of temple and palace, reaching their zenith around India around 2nd C.E. onwards and under the powerful Gupta empire, when canons of perfection were laid down in detailed treatise - the Natyashastra and the Kamasutra - which are still followed to this day. Through the ages, rival kings and nawabs vied with each other to attract the most renowned artists and performers to their courts. While the classical arts thus became distinct from their folk roots, they were never totally alienated from them, even today there continues a mutually enriching dialogue between tribal and folk forms on the one hand, and classical art on the other; the latter continues to be invigorated by fresh folk forms, while providing them with new thematic content in return. -

June 2017.Pmd

Torch Bearers Padma Sharma: CONTENTSCONTENTS An Exceptional Guru Cover 10 18 Story Rays of Kumari Kamala: 34 Hope A True Inspiration Dr Dwaram Tyagaraj: A Musician with a Big Heart Cultural Beyond RaysBulletin of Hope Borders The Thread of • Expressions34 of Continuity06 Love by Sri Krishna - Viraha Reviews • Jai Ho Russia! Reports • 4th Debadhara 52 Dance Festival • 5 Art Forms under One Roof 58 • 'Bodhisattva' steals the show • Resonating Naatya Tarang • Promoting Unity, Peace and Indian Culture • Tyagaraja's In Sight 250th Jayanthi • Simhapuri Dance Festival: A Celebrations Classical Feast • Odissi Workshop with Guru Debi Basu 42 64 • The Art of Journalistic Writing Tributes Beacons of light Frozen Mandakini Trivedi: -in-Time An Artiste Rooted in 63 Yogic Principles 28 61 ‘The Dance India’- a monthly cultural magazine in "If the art is poor, English is our humble attempt to capture the spirit and culture of art in all its diversity. the nation is sick." Editor-in-Chief International Coordinators BR Vikram Kumar Haimanti Basu, Tennessee Executive Editor Mallika Jayanti, Nebrasaka Paul Spurgeon Nicodemus Associate Editor Coordinators RMK Sharma (News, Advertisements & Subscriptions) Editorial Advisor Sai Venkatesh, Karnataka B Ratan Raju Kashmira Trivedi, Thane Alaknanda, Noida Contributions by Lakshmi Thomas, Chennai Padma Shri Sunil Kothari (Cultural Critic) Parinithi Gopal, Sagar Avinash Pasricha (Photographer) PSB Nambiar Sooryavamsham, Kerala Administration Manager Anurekha Gosh, Kolkata KV Lakshmi GV Chari, New Delhi Dr. Kshithija Barve, Goa and Kolhapur Circulation Manager V Srinivas Technical Advise and Graphic Design Communications Incharge K Bhanuji Rao Articles may be submitted for possible publication in the magazine in the following manner. -

Pandit Ravi Shankar—Tansen of Our Times

Occ AS I ONAL PUBLicATION 47 Pandit Ravi Shankar—Tansen of our Times by S. Kalidas IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE 40, MAX MUELLER MARG , NEW DELH I -110 003 TEL .: 24619431 FAX : 24627751 1 Occ AS I ONAL PUBLicATION 47 Pandit Ravi Shankar—Tansen of our Times The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and not of the India International Centre. The Occasional Publication series is published for the India International Centre by Cmde. (Retd.) R. Datta. Designed and produced by FACET Design. Tel.: 91-11-24616720, 24624336. Pandit Ravi Shankar—Tansen of our Times Pandit Ravi Shankar died a few months ago, just short of his 93rd birthday on 7 April. So it is opportune that we remember a man whom I have rather unabashedly called the Tansen of our times. Pandit Ravi Shankar was easily the greatest musician of our times and his death marks not only the transience of time itself, but it also reminds us of the glory that was his life and the immortality of his legacy. In the passing of Robindro Shaunkar Chowdhury, as he was called by his parents, on 11 December in San Diego, California, we cherish the memory of an extraordinary genius whose life and talent spanned almost the whole of the 20th century. It crossed all continents, it connected several genres of human endeavour, it uplifted countless hearts, minds and souls. Very few Indians epitomized Indian culture in the global imagination as this charismatic Bengali Brahmin, Pandit Ravi Shankar. Born in 1920, Ravi Shankar not only straddled two centuries but also impacted many worlds—the East, the West, the North and the South, the old and the new, the traditional and the modern. -

Bridging the Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances As a Source of Dance/Movement Therapy, a Literature Review

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses (GSASS) Spring 5-16-2020 Bridging The Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review. Ruta Pai Lesley University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses Part of the Art Education Commons, Counseling Commons, Counseling Psychology Commons, Dance Commons, Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pai, Ruta, "Bridging The Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review." (2020). Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses. 234. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses/234 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. BRIDGING THE GAP 1 Bridging the Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review. Capstone Thesis Lesley University August 5, 2019 Ruta Pai Dance/Movement Therapy Meg Chang, EdD, BC-DMT, LCAT BRIDGING THE GAP 2 ABSTRACT Indian Classical Dances are a mirror of the traditional culture in India and therefore the people in India find it easy to connect with them. These dances involve a combination of body movements, gestures and facial expressions to portray certain emotions and feelings. -

A North Indian Classical Dance Form: Lucknow Kathak

100 A North Indian Classical Dance Form: Lucknow Kathak Gina Lalli The word 'Kathak' now refers to a school of dancing and 'Kathak dancer' to a practitioner of that school. The old word kathak (story-telling, composition) is a Sanskrit word, as is ka.thaka., which means 'narrator' or 'one who recites'. Both words refer to a tradition of dramatic recitation, utilizing gestures and musical accompaniment, of religious teachings still practiced in the temples of Ind.ia. 1 The main schools of Kathak originated in Luck.now, Benares, Jaipur and (later on), Lahore. These schools have a general form in common, but they differ in emphasis of some facet of the dance form. Lucknow Kathak is noted for its development of the pantomimic part of the dance and for its balance bet\.veen storytelling and more abstract aspects of the dance having no stories attached to them. It would be difficult to trace the history of Lucknow Kathak with any accu racy beyond the past one hundred fifty years. It is known that in the early nineteenth century, Mo brothers, Thakur and Durga Prasad, migrated to 2 Lucknow from Rajastan or Jodhpur (from Khokar 1959 and Birju Maharaj ). The then ruler of Lucknow, Wajid Ali Shah, was a great patron of the arts who, recognizing Durga Prasad's mastery as a dancer and musidan, invited him to be his court musician and dance teacher. According to Birju Marharaj, Durga Prasad taught the dance to his own sons, Kalkadin and Bindadin. The brothers were devoted, together deciding that only one of them would marry so that the other, free from the economic responsibilities of marriage, could spend his life in the practice and teaching of Kathak. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full -

Social Attitude Towards Theatre Actresses in 19 Century Bengal

www.ijird.com February, 2016 Vol 5 Issue 3 ISSN 2278 – 0211 (Online) Social Attitude towards Theatre Actresses in 19 th Century Bengal Dr. Sushmita Sengupta Assistant Professor, Department of History, Baruipur College, West Bengal, India Abstract: The 19 th century the ‘age of reasons and reform’ in Bengal saw the question of the theatre actress come to the forefront. With the gradual introduction of the female actress on the stage, they became the figure head on whom the ambivalences and contradictions of the age was manifested. The colonial government had set out to ‘civilize’ the ‘barbaric’ India. The performing artists who had a close association with the courtesan class became the target of the colonizers. Theatre activity was first undertaken by the newly educated Bengali middleclass, who shared the same view of their colonial masters regarding the theatre actresses. The first generation of Bengali actresses remained marginalized in the theatre space. Socially stigmatized and exploited on and off stage, these theatre actresses remained a pawn in the whole set of rules formed by the urban educated middleclass society. Keywords: Reason, reform, theatre, actress, colonial, government, intelligentsia, marginalized. Since time immemorial art and culture has been an inseparable aspect of human life. Art in all its forms has preserved the culture and social system of a particular period or era. The visual arts like “natya” have had a direct contact with the minds of the viewers and the impact of such media on the human mind has been like a photo imprint. So whatever the artist has visually created on the stage has influenced the mind and worked slowly and diligently to change the attitudes and habits of the society. -

Kathak Through the Ages, the Last Choreography of Guru Maya Rao in 2014, Video Projection in the Background Adds to the Dynamism of the Choreography

PAPER 4 Detail Study Of Kathak, Nautch Girls, Nritta, Nritya, Different Gharana-s, Present Status, Institutions, Artists Module 20 Modern Development And Future Trends In Kathak Kathak though an ancient dance form, with clear established history, has grown to a massive body of work, making it veer towards what is contemporary and modern. The words contemporary and modern are two different terms in context of art. Any art form, design, film, fashion, music can be contemporary. Each generation or time cycle brings something to the table of this development in society but modern means a whole new language. It means new structure, new grammar and new form. So, in dance when we speak of a modern Kathak, what does it imply? Kathak has certain grammar and structure, as with any and most dance forms. Thus, when we say modern Kathak, it doesn’t mean we break the grammar or change costume - that is just innovation or making it more in tune with contemporary desires of a society at any given point of time. 1 Many believe that Kumudhini Lakhia’s solo performance entitled Duvidha was a turning point of Kathak as a dance form. She founded the Kadamb School of Dance and Music in Ahmedabad in 1967 and has done more than 70 successful productions all over the world. Her choreographies include Dhabkar / धबकार, Yugal / युगऱ, Atah Kim / अथ: ककम, The Peg, Okha-Haran / ओखा हरण, Sama Samvadan / सम संवाद, Suverna / सुवण,ण Bhav Krida / भाव क्रीड़ा, Golden Chains, Kolaahal / कोऱाहऱ, Mushti / मुष्टि to name a few.