Kathak Through the Ages, the Last Choreography of Guru Maya Rao in 2014, Video Projection in the Background Adds to the Dynamism of the Choreography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

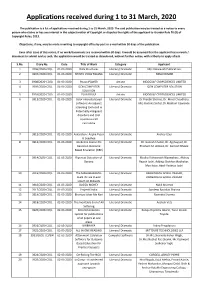

Applications Received During 1 to 31 March, 2020

Applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020 The publication is a list of applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020. The said publication may be treated as a notice to every person who claims or has any interest in the subject matter of Copyright or disputes the rights of the applicant to it under Rule 70 (9) of Copyright Rules, 2013. Objections, if any, may be made in writing to copyright office by post or e-mail within 30 days of the publication. Even after issue of this notice, if no work/documents are received within 30 days, it would be assumed that the applicant has no work / document to submit and as such, the application would be treated as abandoned, without further notice, with a liberty to apply afresh. S.No. Diary No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 3906/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Data Structures Literary/ Dramatic M/s Amaravati Publications 2 3907/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 SHISHU VIKAS YOJANA Literary/ Dramatic NIRAJ KUMAR 3 3908/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 Picaso POWER Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 4 3909/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 ICON COMPUTER Literary/ Dramatic ICON COMPUTER SOLUTION SOLUTION 5 3910/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 PLANOGULF Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 6 3911/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Color intensity based Literary/ Dramatic Dr.Preethi Sharma, Dr. Minal Chaudhary, software: An adjunct Mrs.Ruchika Sinhal, Dr.Madhuri Gawande screening tool used in Potentially malignant disorders and Oral squamous cell carcinoma 7 3912/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Aakarshan : Aapke Pyaar Literary/ Dramatic Akshay Gaur ki Seedhee 8 3913/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Academic course file Literary/ Dramatic Dr. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Classical Dances Have Drawn Sustenance

Performing Art 1 Classic Dances 4 Bharatnatyam Dance 8 Kathakali Dance 12 Kathak Dance 18 Manipuri 21 Lai Haraoba 22 Radha and Krishna 23 Pung Cholam 23 Kartal Cholam 23 Thang-Ta 24 Musicians 24 Odissi 25 Kuchipudi 30 Sattriya 34 Performing Art In India, various facets of performing arts are all pervading bringing colour and joy to numerous festivals and ceremonies, and reaffirming the faith of the people in their heritage. These facets have been responsible for sustaining the long continuities of ancient traditions. They are the link between the past and the present. It thus exemplifies the complex, organic interaction of all aspects of life implicit in all tribal and folk art forms; art is not seen as something apart from life, a mere ornamentation or entertainment, but as an intrinsic part of it. Page !1 of !36 Pre-historic Cave painting, Bhimbetka, Madhya Pradesh Under the patronage of Kings and rulers, skilled artisans and entertainers were encouraged to specialize and to refine their skills to greater levels of perfection and sophistication. Gradually, the classical forms of Art evolved for the glory of temple and palace, reaching their zenith around India around 2nd C.E. onwards and under the powerful Gupta empire, when canons of perfection were laid down in detailed treatise - the Natyashastra and the Kamasutra - which are still followed to this day. Through the ages, rival kings and nawabs vied with each other to attract the most renowned artists and performers to their courts. While the classical arts thus became distinct from their folk roots, they were never totally alienated from them, even today there continues a mutually enriching dialogue between tribal and folk forms on the one hand, and classical art on the other; the latter continues to be invigorated by fresh folk forms, while providing them with new thematic content in return. -

Times-NIE-Web-Ed-AUGUST 14-2021-Page3.Qxd

CELLULAR JAIL, ANDAMAN & BIRLA HOUSE: Birla House is a muse- NICOBAR ISLANDS: Also known as um dedicated to Mahatma Gandhi. It ‘Kala Pani’, the British used the is the location where Gandhi spent CELEBRATING FREEDOM jail to exile political prisoners at the last 144 days of his life and was SATURDAY, AUGUST 14, 2021 03 this colonial prison assassinated on January 30, 1948 CLICK HERE: PAGE 3 AND 4 Pre-Independence slogans and its relevance in India today Slogans raised by leaders during the freedom movement set the mood of the nation’s revolution for its independence. They epitomised the struggle and hopes of millions of Indians. Author and former ad guru ANUJA CHAUHAN revisits these powerful slogans and explains their history and relevance in a contemporary India SATYAMEV JAYATE QUIT INDIA LIKE SWARAJ, KHADI IS (Truth alone triumphs) HISTORY: This slogan is widely associ- OUR BIRTH-RIGHT ated with Mahatma Gandhi (what he HISTORY: Inscribed at the base of started was the Quit India Movement India’s national emblem, this phrase is from August 8, 1942, in Bombay (then), a mantra from the ancient Indian scr- but the term ‘Quit India’ was actually ipture, ‘Mundaka Upanishad’, which coined by a lesser-known hero of was popularised by freedom fighter India’s freedom struggle – Yusuf Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya during Meherally. He had published a booklet India’s freedom movement. titled ‘Quit India’ (sold in weeks) and got over a thousand ‘Quit India’ badges to give life to the slogan that Gandhi also started using and popularised. ‘YOUNGSTERS, DON’T QUIT INDIA’: Quit India was a powerful slogan and HISTORY: Mahatma Gandhi’s call to as a slogan) was written by Urdu the jingle of an epic movement meant use khadi became a movement for poet Muhammad Iqbal in 1904 for to drive the British away from our the indigenous swadeshi (Indian) children. -

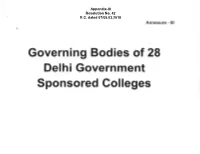

Governing Bodies of 28 Delhi Government Sponsored Colleges Appendix-III Resolution No

Appendix-III Resolution No. 42 E.C. dated 07/08.03.2018 Annexure- Ill I Governing Bodies of 28 Delhi Government Sponsored Colleges Appendix-III Resolution No. 42 E.C. dated 07/08.03.2018 Acharya Narendra Dev• College Delhi Government Nominee S.No. Name Profession Affiliation Residence Phone Email 1 Prof. Anwar Alam Ed ucationist JNU School of Language, · Literature and 9868319298 - Culture Studies, Jawahar Lal University, New Delhi - 67 2 Surender Jaglan Social Worker Former Teacher in Kendriya 0/59, 3rd Floor, Pandav Nagar, Delhi 8588833513 Vidhyalaya Delhi University Panel S.No. Name Profession Affiliation Residence Phone Email I Ms. Meena Mani Architect Mani Chowfla. Architects Consultants, 011-41327564 contact@manichowfla. com 5613 Friends Colony East, Delhi - 110065 2 Justice Usha Mehra Judge Delhi High Court B-57, Defence Colony 9818421144 j [email protected]. in New Delhi - II 0024 3 Dr. Madhavi Diwan Advocate 9, Nizamuddin East, New Delhi - 9873819504 110013 4 Prof. Atiqur Rahman Dept. of Geography, Plot No. 35, Flat No. 302, Zakir Nagar 9873115404 [email protected]. in Jamia Millia Tslamia !(West) New Delhi - II 0025 5 Tapas Sen Media specialist Executive Vice President 3rd Florr, Times Center, Plot No. 6, 9810301383 [email protected] Journalist Times of India Group & Sector 16A, Film City, Noida Chief Programming Officer, Radio Mirchi Appendix-III Resolution No. 42 E.C. dated 07/08.03.2018 Aditi Mahavidyalaya Delhi Government Nominee S.No. Name P'rofession Affiliation Residence . Phone Email I Prabhanjan Jha Educationist Delhi Atithi Shikshak Sangh 4498 A, B-1 10/10, Sant Nagar (Burari), 8447747601 Delhi -84 2 Dharam Veer Sharma Advocate Udbhos (NGO) B-4/205, Sector-7, Rohini, Delhi - 9810883384 110085. -

Bridging the Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances As a Source of Dance/Movement Therapy, a Literature Review

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses (GSASS) Spring 5-16-2020 Bridging The Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review. Ruta Pai Lesley University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses Part of the Art Education Commons, Counseling Commons, Counseling Psychology Commons, Dance Commons, Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pai, Ruta, "Bridging The Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review." (2020). Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses. 234. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses/234 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. BRIDGING THE GAP 1 Bridging the Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review. Capstone Thesis Lesley University August 5, 2019 Ruta Pai Dance/Movement Therapy Meg Chang, EdD, BC-DMT, LCAT BRIDGING THE GAP 2 ABSTRACT Indian Classical Dances are a mirror of the traditional culture in India and therefore the people in India find it easy to connect with them. These dances involve a combination of body movements, gestures and facial expressions to portray certain emotions and feelings. -

General Knowledge Objective Quiz

Brilliant Public School , Sitamarhi General Knowledge Objective Quiz Session : 2012-13 Rajopatti,Dumra Road,Sitamarhi(Bihar),Pin-843301 Ph.06226-252314,Mobile:9431636758 BRILLIANT PUBLIC SCHOOL,SITAMARHI General Knowledge Objective Quiz SESSION:2012-13 Current Affairs Physics History Art and Culture Science and Technology Chemistry Indian Constitution Agriculture Games and Sports Biology Geography Marketing Aptitude Computer Commerce and Industries Political Science Miscellaneous Current Affairs Q. Out of the following artists, who has written the book "The Science of Bharat Natyam"? 1 Geeta Chandran 2 Raja Reddy 3 Saroja Vaidyanathan 4 Yamini Krishnamurthy Q. Cricket team of which of the following countries has not got the status of "Test" 1 Kenya 2 England 3 Bangladesh 4 Zimbabwe Q. The first Secretary General of the United Nation was 1 Dag Hammarskjoeld 2 U. Thant 3 Dr. Kurt Waldheim 4 Trygve Lie Q. Who has written "Two Lives"? 1 Kiran Desai 2 Khushwant Singh 3 Vikram Seth 4 Amitabh Gosh Q. The Headquarters of World Bank is situated at 1 New York 2 Manila 3 Washington D. C. 4 Geneva Q. Green Revolution in India is also known as 1 Seed, Fertiliser and irrigation revolution 2 Agricultural Revolution 3 Food Security Revolution 4 Multi Crop Revolution Q. The announcement by the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited Chairmen that India is ready to sell Pressurised 1 54th Conference 2 53rd Conference 3 51st Conference 4 50th Conference Q. A pension scheme for workers in the unorganized sector, launched recently by the Union Finance Ministry, has been named 1 Adhaar 2 Avalamb 3 Swavalamban 4 Prayas Q. -

Bravely Fought the Queen

INTRODUCTION “My life is big. I am BIG and GENEROUS! Only the theatre deserves me” (Where Did I Leave My Purdah? 59) Theatre has always been a glorious star in the multi-dimensional and richly adorned cultural galaxy of India. But Indian English theatre has had a rather low key representation in this vibrant cultural arena. During the sixties and seventies European influence, especially of Pirandello, Brecht, Chekhov and others, gained prominence and helped Indian theatre express the fractured reality of the time. But the indigenous Indian theatre moved past regional boundaries to become really a polyglot phenomenon from the sixties onward, and use of English helped it cross the border of language, too. Nissim Ezekiel, Girish Karnad, Badal Sircar and Vijay Tendulkar were the chief architects of this aesthetic/cultural development. But except for a few plays written in English between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and for the translations in English of the works of the above playwrights, the picture of Indian drama in English, however, appeared rather uninspiring. It was not until the eighties that English drama stepped out of the coterie of elitists and reached a wider audience. The efforts of playwrights like Nissim Ezekiel, Asif Currimbhoy, Shib K Kumar and others achieved occasional success, but failed to connect the audience with theatre’s full potential. With a younger group of 1 playwrights a more lasting change was visible, and the plays by Dina Mehta, Poli Sengupta, Manjula Padmanavan, and Tripurari Sharma found increasingly appreciative audience. It was with the appearance of Mahesh Dattani in the 1980s that Indian English drama gained a distinct identity. -

Cultural History of Indian Subcontinent; with Special Reference to Arts and Music

1 Cultural History of Indian subcontinent; with special reference to Arts and Music Author Raazia Hassan Naqvi Lecturer Department of Social Work (DSW) University of the Punjab, www.pu.edu.pk Lahore, Pakistan. Co-Author Muhammad Ibrar Mohmand Lecturer Department of Social Work (DSW) Institute of Social Work, Sociology and Gender Studies (ISSG) University of Peshawar, www.upesh.edu.pk Peshawar, Pakistan. 2 Introduction Before partition in 1947, the Indian subcontinent includes Pakistan, India and Bangladesh; today, the three independent countries and nations. This Indian Subcontinent has a history of some five millennium years and was spread over the area of one and a half millions of square miles (Swarup, 1968). The region is rich in natural as well as physical beauty. It has mountains, plains, forests, deserts, lakes, hills, and rivers with different climate and seasons throughout the year. This natural beauty has deep influence on the culture and life style of the people of the region. This land has been an object of invasion either from the route of mountains or the sea, bringing with it the new masses and ideas and assimilating and changing the culture of the people. The invaders were the Aryans, the Dravidians, the Parthians, the Greeks, the Sakas, the Kushans, the Huns, the Turks, the Afghans, and the Mongols (Singh, 2008) who all brought their unique cultures with them and the amalgamation gave rise to a new Indian Cilvilization. Indus Valley Civilization or Pre-Vedic Period The history of Indian subcontinent starts with the Indus Valley Civilization and the coming of Aryans both are known as Pre-Vedic and Vedic periods. -

Sept17 Cal Box.Cdr

Dear Member, September arrives with tremendous promise marked by standalone Quality Street Sat Bhashe Raidas initiatives designed to transform your urban experience! (English/60mins) (Hindi/95mins) Habitat Film Club Notably, IHC, in collaboration with the Ministry of Youth Affairs & Dir. Rasika Agashe Presents A solo directed & performed Sports, begins the Khelo India Series, a quarterly lecture series Writ. Rajesh Kumar A Festival of Iranian Cinema featuring sports icons who will discuss their vision and share life by Maya Krishna Rao Prod. Being Association Collab. Iran Culture House, New Delhi based on a short story by experiences. A platform that aims to nurture sports culture in the 3 Sept 7:00pm|Bodyguard (Persian/2016/95mins) Dir. Ebrahim country and generate valuable insights on sports policy, infrastructure Chimamanda Adichie Hatamikia and opportunities, the maiden lecture on 4 Sept will be delivered by 4 Sept 7:00pm | Sweet Taste of Imagination (Persian/2014/90mins) 22 Sept | 7:00pm Pullela Gopichand, Chief National Coach of the Indian Badminton 9 Sept | 7:30pm Dir. Kamal Tabrezi The Amphitheatre, IHC Team. It is only apt that his lecture falls on the eve of Teacher's Day The Stein Auditorium 5 Sept 7:00pm | Crazy Castle (Persian/2015/115mins) Dir. Abdolhasan Davoodi celebrated across the country in honour of the enduring interventions of For 10 years & above the teaching community. Tickets at Rs.500, Rs.350 & Rs.200 11 Sept 7:00pm | Where are My Shoes (Persian/2016/90mins) Tickets at Rs.300 from 1 Sept. for IHC members Dir. Kioumars Pourahmad available at the Programmes Desk IHC will collaborate with Research and Information System for & open to all from 4 Sept. -

Men in Dance with Special Emphasis on Kuchipudi, a South Indian

Men in Dance with Special Emphasis on Kuchipudi, a South Indian Classical Dance Tradition Presented at International Word Congress of Dance Research By Rajesh Chavali (MA Kuchipudi) Introduction India is a country of diverse languages, religions, cultures and castes, all assimilated seamlessly with great integrity. We must acknowledge this is not a political decision but rather a course of evolution and history. A historic perspective of ancient India with several invasions and rulers of India that didn’t belong to that land influenced a lot of what we see in todays’ India. As we can imagine and nothing out of ordinary, India has seen several intrinsic and extrinsic influences including socioeconomic condition, political influences, power struggle, hierarchy in the caste system, acceptance of the roles of man and woman in the social ecosystem, development and adoption of a variety of religions and philosophical schools of thoughts. For the scope of the current paper at this congress, I’ll focus briefly on these influences and how Indian dances evolved over time and will present more detailed discussion of origin of Kuchipudi, a south Indian classical dance form as a male tradition in Indian classical dance history to its current state. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Influences on Developing India over the Years India, as a country, has undergone several political invasions, major influencers being Mughal and British invasions. The existing cultural dances of India (classical or other non-classical forms or non-classical forms of those times that later attained classical status) in parts of the country were heavily influenced by these invasions while the relatively untouched or inaccessible parts of India, such as northeast part of India largely retained their identity. -

1481178219P3M27TEXT.Pdf

PAPER: 3 Detail Study Of Bharatanatyam, Devadasis-Natuvnar, Nritya And Nritta, Different Bani-s, Present Status, Institutions, Artists Module 27 Modern Development And Future Trends In Bharatanatyam Present day Bharatanatyam is progressing to a new avatar while partaking of old structure and substance. Each new person, educated, city-bred, global, is trying to infuse new energy and light into this form. Many have succeeded tremendously (as in the case of Malavika Sarukkai) in giving it a new dimension, while others (Alarmel Valli) have retained its classical roots and gone back in time to bring back gems of bygone era (Sangam poetry, etc.). Some have used group works (Leela Samson) to create anew and some have gone beyond the solo structure and infused it with group dynamics (B. Bhanumati). What we see are not new banis but new bodies and groups being created. Bani / बानी is now a reference point. Only few retain and guard it without alloying or diluting. While each one comes with certain historical reference point called bani/training, they have all tried to create anew. Partly due to demands of each season and what new work each capable star dancer can present and partly because of sponsors clamoring for new wine in old bottles or vice versa! But Bharatanatyam remains quintessentially the same. Its structure can be marginally changed but form is same. Bent at knee 1 legs are bent at knee legs because that’s what the style’s structure demands (called araimandi / अरैमंडी). One may make the fan of costume longer so one has to sit less! But the basic position still remains that else it can’t qualify to be called Bharatanatyam.