Bravely Fought the Queen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflection of Marriage and Family in Vijay Tendulkar's Play

REFLECTION OF MARRIAGE AND FAMILY IN VIJAY TENDULKAR’S PLAY “KAMALA” FADL MOHAMMED AIED ALGALHADI DR. SHAILAJA B. WADIKAR Ph D. Research Scholar Dep. of English Associate Professor School of Lang. Lit. & Culture School of Lang. Lit. & Culture S. R. T. M. U. Nanded S. R. T. M. University, Nanded (MS) INDIA (MS) INDIA A drama as part of literature is admittedly a convenient way for showing social problems of society in which story is told to the audience through the performance on the stage by the actors. The present paper aims to study Vijay Tendulkar’s ideas about marriage family in his play Kamala. The play is based on a real life incident. Kamala is a play that elucidates the predicament of women. The play explores how women have been treated by male counterparts. Women are oppressed, misused, exploited, and enslaved. Kamala shows how women are used as a means for fulfillment of men's lust, ambition, fame, and money. The paper presents the horrible exploitation of women in the rural area of India where women can be bought from a flesh market .It aims to show the reality of life of women in modern India especially the concept of marriage and family. This paper will focus on the theme of exploitation which is found in the marital relationship in this play. Key Words: Vijay Tendulkar, Marriage, Family, Exploitation, Kamala, Drama, Women. INTRODUCTION Drama is the form of composition designed for performance in the theater, in which actors take the role of the characters, perform the indicated action, and utter the written dialogue(M.H.Abram ).According to Dryden“drama is just and lively image of human nature, representing its passions and humors, and the changes of fortune to which it is subjected, for the delight and instruction of mankind.”Drama in India has ancient history. -

Mentors – Katha

Mentors – Katha about our work act now 300m storyshop .ST0{DISPLAY:NONE;} .ST1{DISPLAY:INLINE;} KATHA UTSAV MENTORS ARUNIMA MAZUMDAR, WRITER & JOURNALIST Arunima works with Roli Books, one of the foremost Indian publishing houses of India. She has worked as a journalist in the past and ABOUTcontinues to US write on arts, culturePROGRAMMES and travel for various publicationsQUICKLINKS such as The Hindu Business Line, Scroll, Femina, and Mumbai Mirror. Books are her best friend and she has keen interest in travel literature, written especially by Who we are 300M Donate Indian authors. Katha Books Katha Lab School Donate Books Storystop ILR Communities Volunteer ANKIT CHADHA – WRITER & STORYTELLER KATHA, A3, Sarvodaya Katha in the News ILR Government Schools Who we are Enclave, Sri AurobindoAnkit ChadhaWhat’s isour a writer-storytellerType whoKatha brings Utsav together performance, literatureWork With and Us history. He specializes in Dastangoi – the Marg, New Delhi - 110017art of Urdu storytelling, and has written, translated, compiled and performed stories under the direction of Mahmood Padho Pyar Se Contact Us Farooqui. His first book for children, the national award-winning My Gandhi Story was published by Tulika in 2013. © Copyright 2017. All Rights Reserved ARVIND GAUR Arvind Gaur, Indian director, is known for his work in innovative, socially and politically relevant theatre.Gaur’s plays are contemporary and thought-provoking, connecting intimate personal spheres of existence to larger social political issues. His work deals with Internet censorship, communalism, caste issues, feudalism, domestic violence, crimes of state, politics of power, violence, injustice, social discrimination, marginalization, and racism. Arvind is the leader of Asmita, Delhi‘s “most prolific theatre group”, and is an actor trainer, social activist, street theatre worker and story teller. -

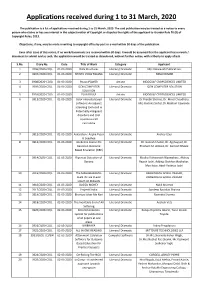

Applications Received During 1 to 31 March, 2020

Applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020 The publication is a list of applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020. The said publication may be treated as a notice to every person who claims or has any interest in the subject matter of Copyright or disputes the rights of the applicant to it under Rule 70 (9) of Copyright Rules, 2013. Objections, if any, may be made in writing to copyright office by post or e-mail within 30 days of the publication. Even after issue of this notice, if no work/documents are received within 30 days, it would be assumed that the applicant has no work / document to submit and as such, the application would be treated as abandoned, without further notice, with a liberty to apply afresh. S.No. Diary No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 3906/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Data Structures Literary/ Dramatic M/s Amaravati Publications 2 3907/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 SHISHU VIKAS YOJANA Literary/ Dramatic NIRAJ KUMAR 3 3908/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 Picaso POWER Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 4 3909/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 ICON COMPUTER Literary/ Dramatic ICON COMPUTER SOLUTION SOLUTION 5 3910/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 PLANOGULF Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 6 3911/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Color intensity based Literary/ Dramatic Dr.Preethi Sharma, Dr. Minal Chaudhary, software: An adjunct Mrs.Ruchika Sinhal, Dr.Madhuri Gawande screening tool used in Potentially malignant disorders and Oral squamous cell carcinoma 7 3912/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Aakarshan : Aapke Pyaar Literary/ Dramatic Akshay Gaur ki Seedhee 8 3913/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Academic course file Literary/ Dramatic Dr. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

Volume 1 on Stage/ Off Stage

lives of the women Volume 1 On Stage/ Off Stage Edited by Jerry Pinto Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media Supported by the Laura and Luigi Dallapiccola Foundation Published by the Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media, Sophia Shree B K Somani Memorial Polytechnic, Bhulabhai Desai Road, Mumbai 400 026 All rights reserved Designed by Rohan Gupta be.net/rohangupta Printed by Aniruddh Arts, Mumbai Contents Preface i Acknowledgments iii Shanta Gokhale 1 Nadira Babbar 39 Jhelum Paranjape 67 Dolly Thakore 91 Preface We’ve heard it said that a woman’s work is never done. What they do not say is that women’s lives are also largely unrecorded. Women, and the work they do, slip through memory’s net leaving large gaps in our collective consciousness about challenges faced and mastered, discoveries made and celebrated, collaborations forged and valued. Combating this pervasive amnesia is not an easy task. This book is a beginning in another direction, an attempt to try and construct the professional lives of four of Mumbai’s women (where the discussion has ventured into the personal lives of these women, it has only been in relation to the professional or to their public images). And who better to attempt this construction than young people on the verge of building their own professional lives? In learning about the lives of inspiring professionals, we hoped our students would learn about navigating a world they were about to enter and also perhaps have an opportunity to reflect a little and learn about themselves. So four groups of students of the post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media, SCMSophia’s class of 2014 set out to choose the women whose lives they wanted to follow and then went out to create stereoscopic views of them. -

Syllabus of Arts Education

SYLLABUS OF ARTS EDUCATION 2008 National Council of Educational Research and Training Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi - 110016 Contents Introduction Primary • Objectives • Content and Methods • Assessment Visual arts • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Theatre • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Music • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Dance • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Heritage Crafts • Higher Secondary Graphic Design • Higher Secondary Introduction The need to integrate art s education in the formal schooling of our students now requires urgent attention if we are to retain our unique cultural identity in all its diversity and richness. For decades now, the need to integrate arts in the education system has been repeatedly debated, discussed and recommended and yet, today we stand at a point in time when we face the danger of lo osing our unique cultural identity. One of the reasons for this is the growing distance between the arts and the people at large. Far from encouraging the pursuit of arts, our education system has steadily discouraged young students and creative minds from taking to the arts or at best, permits them to consider the arts to be ‘useful hobbies’ and ‘leisure activities’. Arts are therefore, tools for enhancing the prestige of the school on occasions like Independence Day, Founder’s Day, Annual Day or during an inspection of the school’s progress and working etc. Before or after that, the arts are abandoned for the better part of a child’s school life and the student is herded towards subjects that are perceived as being more worthy of attention. General awareness of the arts is also ebbing steadily among not just students, but their guardians, teachers and even among policy makers and educationalists. -

Following Are Some of the Books by Indian Authors Book Name Author

Following are some of the books by Indian Authors Book Name Author A bend in the river V.S. Naipal A brush with life Satish Gujral A House of Mr. Biswar V.S. Naipal A Million Mutinies Now V.S. Naipal A Passage to England Nirad C.Chodhury A Prisoner’s Scrapbook L.K. Advani A River Sutra Gita Mehra A sense of time H.S.Vatsyayan A strange and subline address Amit Chaudhary A suitable boy Vikram Seth A village by the sea Anita Desai A voice for freedom Nayantara Sehgal Aansoo Suryakant Tripathi Nirala Afternoon Raag Amit Chaudhari Ageless Body, Timeless Mind Deepak Chopra Agni Veena Kazi Nazrul Islam Ain-i-Akbari Abul Fazal Amar Kosh Amar Singh An autobiography Jawaharlal Nehru An Equal Music Vikram Seth An Idealist View of life Dr. S. Radhakrishan Amrit Aur Vish Amrit Lal Nagar Anamika Suryakant Tripathi Nirala Anandmath Bankim Chandra Chatterjee Areas of Darkness V.S. Naipal Arthashastra Lautilya Ashtadhyayi Panini Autobiography of an Unknown India Nirad C. Choudhury Bandicoot Run Manohar Malgonkar Beginning of the Beginning Bhagwan Shri Rajneesh Between the Lines Kuldip Nayyar Beyond Modernisation, Beyond Self Sisirkumar Ghose Bhagvad Gita Ved Vyas Bharat Bharati Maithilisharan Gupt Bharat Durdasha Bhartendu Harischandra Border and Boundaries: women in India’s Ritu Menon & Kamla Bhasin Partition Bharat Bharati Maithili Saran Gupt Breaking the Silence Anees Jung Bride and the Sahib and the other stories Khushwant Singh Broken Wings Sarojini Naidu Bubble, The Mulk Raj Anand Buddha Charitam Ashwaghosh By God’s Decree Kapil Dev Chandalika Rabindra Nath Tagore Chandrakanta Santati Devkinandan Khatri Chemmen: Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai Chitra Rabindranath Tagore Chitralekha Bhagwati Charan Verma Chitrangada Rabindra Nath Tagore Circle of Reason Amitav Ghosh Clear Light of Day Anita Desai Confessions of a Lower Mulk Raj Anand Confrontation with Pakistan B. -

List of Documentary Films Produced by Sahitya Akademi

Films Produced by Sahitya Akademi (Till Date) S.No. Author Directed by Duration 1. Amrita Pritam (Punjabi) Basu Bhattacharya 60 minutes 2. Akhtar-ul-Iman (Urdu) Saeed Mirza 60 minutes 3. V.K. Gokak (Kannada) Prasanna 60 minutes 4. Takazhi Sivasankara Pillai (Malayalam) M.T. Vasudevan Nair 60 minutes 5. Gopalkrishna Adiga (Kannada) Girish Karnad 60 minutes 6. Vishnu Prabhakar (Hindi) Padma Sachdev 60 minutes 7. Balamani Amma (Malayalam) Madhusudanan 27 minutes 8. Vinda Karandikar (Marathi) Nandan Kudhyadi 60 minutes 9. Annada Sankar Ray (Bengali) Budhadev Dasgupta 60 minutes 10. P.T. Narasimhachar (Kannada) Chandrasekhar Kambar 27 minutes 11. Baba Nagarjun (Hindi) Deepak Roy 27 minutes 12. Dharamvir Bharti (Hindi) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 13. D. Jayakanthan (Tamil) Sa. Kandasamy 27 minutes 14. Narayan Surve (Marathi) Dilip Chitre 27 minutes 15. Bhisham Sahni (Hindi) Nandan Kudhyadi 27 minutes 16. Subhash Mukhopadhyay (Bengali) Raja Sen 27 minutes 17. Tarashankar Bandhopadhyay (Bengali) Amiya Chattopadhyay 27 minutes 18. Vijaydan Detha (Rajasthani) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 19. Navakanta Barua (Assamese) Gautam Bora 27 minutes 20. Mulk Raj Anand (English) Suresh Kohli 27 minutes 21. Gopal Chhotray (Oriya) Jugal Debata 27 minutes 22. Qurratulain Hyder (Urdu) Mazhar Q. Kamran 27 minutes 23. U.R. Anantha Murthy (Kannada) Krishna Masadi 27 minutes 24. V.M. Basheer (Malayalam) M.A. Rahman 27 minutes 25. Rajendra Shah (Gujarati) Paresh Naik 27 minutes 26. Ale Ahmed Suroor (Urdu) Anwar Jamal 27 minutes 1 27. Trilochan Shastri (Hindi) Satya Prakash 27 minutes 28. Rehman Rahi (Kashmiri) M.K. Raina 27 minutes 29. Subramaniam Bharati (Tamil) Soudhamini 27 minutes 30. O.V. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR TH THURSDAY,THE 20 FEBRUARY,2014 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 1 TO 43 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 44 TO 45 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 46 TO 59 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 60 TO 74 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 20.02.2014 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 20.02.2014 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-1) HON'BLE THE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SIDDHARTH MRIDUL AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS ____________________________ 1. FAO(OS) 429/2013 RAKESH TALWAR JAYANT K MEHTA,JAWAHAR RAJA CM APPL. 14852/2013 Vs. BINDU TALWAR CM APPL. 2546/2014 2. FAO(OS) 431/2013 BINDU TALWAR JAWAHAR RAJA CM APPL. 14934/2013 Vs. RAKESH TALWAR CM APPL. 2547/2014 3. FAO(OS) 23/2014 SHRI VIKAS AGGARWAL LEX INFINI,P D GUPTA AND CO Vs. SHRI BAL KRISHNA GUPTA AND ORS 4. LPA 417/2013 PREM RAJ N S DALAL,SHOBHNA Vs. LAND AND BUILDING TAKIAR,SIDHARTH PANDA DEPARTMENT AND ORS 5. LPA 444/2013 GIRI RAJ N S DALAL,SHOBHNA Vs. LAND AND BUILDING TAKIAR,YOGESH JAIN DEPARTMENT AND ORS 6. LPA 884/2013 PUNEET KAUSHIK AND ANR AYUSHI KIRAN,AMRIT PAL SINGH Vs. UNION OF INDIA AND ORS 7. W.P.(C) 6654/2011 YAHOO INDIA PVT LTD LUTHRA AND LUTHRA,MANEESHA Vs. UNION OF INDIA AND ANR DHIR,VAKUL SHARMA 8. W.P.(C) 6867/2013 RAGHU NANDAN SHARMA NEERAJ MALHOTRA,T.K. -

Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar's Castes in India

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT For the preparation of this SLM covering the Unit-2 of GE in accordance with the Model Syllabus, we have borrowed the content from the Wiki source, Internet Archive, free online encyclopaedia. Odisha State Open University acknowledges the authors, editors and the publishers with heartfelt thanks for extending their support. GENERIC ELECTIVE IN ENGLISH (GEEG) GEEG-2 Gender and Human Rights BLOCK-2 DR BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR'S CASTES IN INDIA UNIT 1 “ CASTES IN INDIA”: DR BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR UNIT 2 A TEXT ON CASTES IN INDIA”: DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR UNIT 1 : “CASTES IN INDIA”: DR BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR Structure 1.0 Objective 1.1 Introduction 1.2 B.R. Ambedkar 1.2.1 Early life 1.2.2 Education 1.2.3 Opposition to Aryan invasion theory 1.2.4 Opposition to untouchability 1.2.5 Political career 1.2.6 In Popular culture 1.3 Let us Sum up 1.4 Check Your Progress 1.0 OBJECTIVE In this unit we seeks to familiarize the students with issues of inequality, and oppression of caste and race . Points as follows: To analyse and interpret Ambedkar's ideological reflection on social and political aspects and on their reformation, in the light of the characteristics of the social and political order that prevailed in India during his life time and before. To assess the contribution made by Ambedkar as a social reformist, in terms of the development of the down trodden classes in India and with special reference to the Ambedkar Movement. To assess the services rendered by Ambedkar in his various official capacities, for the propagation and establishment of his messages. -

Current Affairs for the Month of August 2020

CURRENT AFFAIRS FOR THE MONTH OF AUGUST 2020 Awards The Dutch author who has been awarded the 2020 International Booker Prize for her book The Discomfort of Evening – Marieke Lucas Rijneveld Persons The Japanese Prime Minister who has announced his decision to resign from the post owing to poor health – Mr. Shinzo Abe The new Election Commissioner appointed to replace Shri Ashok Lavasa who has resigned to join Asian Development Bank – Shri Rajiv Kumar The Governor of Goa who has been appointed the Governor of Meghalaya succeeding Shri Tathagata Roy – Shri Satya Pal Malik The expert committee constituted by Central Govt to consider the logistics and ethical aspects of procuring and administering the COVID-19 vaccine is headed by – Dr. VK Paul The former Lt Governor of Jammu and Kashmir who has been appointed new Comptroller and Auditor General of India succeeding Shri Rajiv Mehrishi – Shri Girish Chandra Murmu The new Lieutenant Governor of Jammu and Kashmir appointed to replace Shri GC Murmu – Shri Manoj Sinha Obituary The well-known Indian classical vocalist of Mewati gharana (and recipient of Padma Shri, Padma Bhushan, Padma Vibhushan and Sangeet Natak Akademi Award) who passed away on 17 August 2020 in New Jersey, USA – Pandit Jasraj The former Indian cricketer and Minister of Youth and Sports of Uttar Pradesh who passed away on 16 August 2020 – Chetan Chauhan The renowned Urdu poet and lyricist who passed away on 11 August 2020 while being treated for COVID-19 – Rahat Indori The Indian theatre director and former director of National