Folklore, Orality and Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Classical Dance Is a Relatively New Umbrella Term for Various Codified Art Forms Rooted in Natya, the Sacred Hindu Musica

CLASSICAL AND FOLK DANCES IN INDIAN CULTURE Palkalai Chemmal Dr ANANDA BALAYOGI BHAVANANI Chairman: Yoganjali Natyalayam, Pondicherry. INTRODUCTION: Dance in India comprises the varied styles of dances and as with other aspects of Indian culture, different forms of dances originated in different parts of India, developed according to the local traditions and also imbibed elements from other parts of the country. These dance forms emerged from Indian traditions, epics and mythology. Sangeet Natak Akademi, the national academy for performing arts, recognizes eight distinctive traditional dances as Indian classical dances, which might have origin in religious activities of distant past. These are: Bharatanatyam- Tamil Nadu Kathak- Uttar Pradesh Kathakali- Kerala Kuchipudi- Andhra Pradesh Manipuri-Manipur Mohiniyattam-Kerala Odissi-Odisha Sattriya-Assam Folk dances are numerous in number and style, and vary according to the local tradition of the respective state, ethnic or geographic regions. Contemporary dances include refined and experimental fusions of classical, folk and Western forms. Dancing traditions of India have influence not only over the dances in the whole of South Asia, but on the dancing forms of South East Asia as well. In modern times, the presentation of Indian dance styles in films (Bollywood dancing) has exposed the range of dance in India to a global audience. In ancient India, dance was usually a functional activity dedicated to worship, entertainment or leisure. Dancers usually performed in temples, on festive occasions and seasonal harvests. Dance was performed on a regular basis before deities as a form of worship. Even in modern India, deities are invoked through religious folk dance forms from ancient times. -

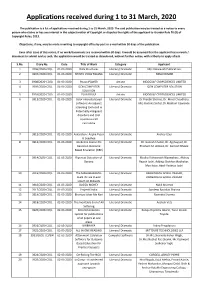

Applications Received During 1 to 31 March, 2020

Applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020 The publication is a list of applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020. The said publication may be treated as a notice to every person who claims or has any interest in the subject matter of Copyright or disputes the rights of the applicant to it under Rule 70 (9) of Copyright Rules, 2013. Objections, if any, may be made in writing to copyright office by post or e-mail within 30 days of the publication. Even after issue of this notice, if no work/documents are received within 30 days, it would be assumed that the applicant has no work / document to submit and as such, the application would be treated as abandoned, without further notice, with a liberty to apply afresh. S.No. Diary No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 3906/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Data Structures Literary/ Dramatic M/s Amaravati Publications 2 3907/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 SHISHU VIKAS YOJANA Literary/ Dramatic NIRAJ KUMAR 3 3908/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 Picaso POWER Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 4 3909/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 ICON COMPUTER Literary/ Dramatic ICON COMPUTER SOLUTION SOLUTION 5 3910/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 PLANOGULF Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 6 3911/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Color intensity based Literary/ Dramatic Dr.Preethi Sharma, Dr. Minal Chaudhary, software: An adjunct Mrs.Ruchika Sinhal, Dr.Madhuri Gawande screening tool used in Potentially malignant disorders and Oral squamous cell carcinoma 7 3912/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Aakarshan : Aapke Pyaar Literary/ Dramatic Akshay Gaur ki Seedhee 8 3913/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Academic course file Literary/ Dramatic Dr. -

Giddha Folk Dance: an Embodiment of Healing Through Creative Artistic Punjabi Dance Culture and Connection with Somatic Dance Therapy & Practice

GIDDHA FOLK DANCE: AN EMBODIMENT OF HEALING THROUGH CREATIVE ARTISTIC PUNJABI DANCE CULTURE AND CONNECTION WITH SOMATIC DANCE THERAPY & PRACTICE Giddha is a form of folk dance from the land of five rivers called Punjab in North- Western part of India. So many rivers in one place signifying fertility and precious land for cultivation and farming. Punjabi culture is filled with vibrancy and fun loving loud people. They believe in expressing themselves with full power and intensity. Punjabi dances are based around energy and happiness. This form has freedom, expression, dramatic voice, facial and body dialoguing. It is a kinaesthetic, preoperceptive and muscular activity with elements of clapping and voicing emotions. It is an act of body, mind and emotions. Clapping helps to release toxins and also can be related to acupressure, as this triggers the points that effect major inner body organs. This form of movement exploration is therapeutic and has the ability to heal from a holistic perspective. Healing here is not when one goes into hospital and finds external source of therapy but from this perspective it simply means uniting the wholeness of being. This supports body, mind and spirit energy, bringing many people together to perform in a sacred circle; thus helping socialising to become artistic and motivational. It allows women of small knit family structures, villages and controlled environment societies to voice their inner feelings and releasing painful toxins through singing, dancing and bodily expression. It gives time to people to release everything in a joking fun loving manner and especially in a non- judgmental circle. -

Dances & States

DANCES & STATES 1. Odisha Odissi Bhaka Wata Dandante 2. Kerala Chakiarkoothu Kathakali Mohiniattam Ottam Thullal Chavittu Natakam Kaikotti Kalai Koodiyattam Krishnavattam Mudiyettu Tappatri Kai Theyyam 3. Tamil nadu Bharatnatyam Kummi Kolattam Devarattam Poikkal Kuthirai Attam Therukkoothu Karakattam Mayilattam Kavadiattam Silambattam Thappattam Kaliattam Puliyattam cracktiss.wordpress.com 4. Andhera pradesh Kuchipudi Veethi-Bhagavatham Kottam 5. Karnataka Yakshagana Bayalata Simha Nutrya Dollu Kunitha Veeragase 6. Assam Bihu Ojapali Ankia Nat 7. Bihar Jat Jatin Faguna or Fag Purbi Bidesia Jhijhian Kajari Sohar-Khilouna Holi Dance Jhumeri Harvesting Dance 8. Gujrat Dandya Ras cracktiss.wordpress.com Garba Lasya Nritya Bhavai Garba Rasila Trippani 9. Haryana Swang Khoria Gugga dance Loor Sang Dhamal 10. Himachal pradesh Luddi Dance Munzra Kanayala Giddha Parhaun 11. Jammu and Kashmir Hikat Rouf Chakri 12. Maharashtra Tamasha Dahi Kala Lavani Lezim cracktiss.wordpress.com 13. Madhya Pradesh Lota Pandvani 14. Meghalaya Wangala Laho Shad Nongkrem Shad Sukmysiem 15. Manipur Manipuri Maha Rasa Lai Haroba 16. Mizoram Chiraw (Bamboo Dance) 17. Punjab Bhangra Gidda 18. Rajasthan Khayal Chamar Gindad Gangore Jhulan Leela Jhumar (Ghumar) Kayanga Bajayanga cracktiss.wordpress.com 19. Uttar Pradesh Kathak Nautanki Chappeli Kajri Karan Kumaon 20. West bengal Jatra Chau Kathi 21. Goa Fugdi Dekhnni Tarangamel Dhalo. 22. Arunachal Pradesh Bardo Chham Aji Lamu Hiirii Khaniing Pasi Kongki Lion and Peacock dance Chalo Popir Ponung Rekham Pada 23. Chhattisgarh cracktiss.wordpress.com Karma Panthi Pandavani Rawat Nacha Soowa Nacha or Suwa Tribal dance 24. Jharkhand Paika Chhou Santhal 25. Nagaland Zeliang Nruirolians (Cock dance) Temangnetin (Fly dance) 26. Sikkim Singhi Chham Yak Chaam Maruni Rechungma 27. Telangana Perini Thandavam Dappu Lambadi Tappeta Gullu 28. -

Orality in Writing: Its Cultural and Political Function in Anglophone African, African-Caribbean, and African-Canadian Poetry

ORALITY IN WRITING: ITS CULTURAL AND POLITICAL FUNCTION IN ANGLOPHONE AFRICAN, AFRICAN-CARIBBEAN, AND AFRICAN-CANADIAN POETRY A Thesis submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Yaw Adu-Gyamfi Spring 1999 © Copyright Yaw Adu-Gyamfi, 1999. All rights reserved. National Ubrary Bib!iotheque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1 A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Vol", ,eferet1C8 Our file Not,e ,life,encs The author has granted a non L' auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format electronique. The author retains ownership of the L' auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permISSlOn. autorisation. 0-612-37868-3 Canada UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN College of Graduate Studies and Research SUMMARY OF DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Yaw Adu-Gyamfi Department of English Spring 1999 -EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Dr. -

List of Indian Folk Dances - State Wise

STUDENT'S SENA New resolution for banking aspirants List of Indian Folk Dances - State Wise List of Folk dances, important for general awareness section of bank exams. Jharkhand Chhanu, Sarahul, Jat-Jatin, Karma, Danga, Bidesia, Sohrai. Uttarakhand Garhwali, Pandav Nritya, Kumaoni, Kajari, Chancheri, Jhora, Raslila, Chhapeli. Andhra Kuchipudi (Classical), Ghanta mardala, Vilasini Pradesh Natyam, Andhra Natyam, Burrakatha, Veeranatyam, Butta bommalu, Tholu Bommalata, Dappu. Chhattisgarh Goudi, Karma, Jhumar, Dagla, Pali, Tapali, Navrani, Diwari, Mundari. Arunachal Mask dance (Mukhauta Nritya), War dance. Pradesh Himachal Jhora, Jhali, Chharhi, Dhaman, Chhapeli, Mahasu, Pradesh Nati, Dangi, Chamba, Thali, Jhainta, Daf, Stick dance etc. Goa Mandi, Jhagor, Khol, Dakni etc. Assam Bihu, Bichhua, Natpuja, Maharas, Kaligopal, Bagurumba, Naga dance, Khel Gopal, Tabal Chongli, Canoe, Jhumura Hobjanai etc. West Bengal Kathi, Gambhira, Dhali, Jatra, Baul, Marasia, Mahal, Keertan etc. Kerala Kathakali (Classical), Ottamthullal, Mohiniyattam, Kaikottikali, Tappeti Kali, Kali Attam. Meghalaya Laho, Baala etc. Manipur Manipuri (Classical), Rakhal, Nat Rash, Maha Rash, Raukhat etc. 1 STUDENT'S SENA New resolution for banking aspirants Nagaland Chong, Lim, Nuralim etc. Orissa Odissi (Classical), Savari, Ghumara, Painka, Munari, Chhau, Chadya Dandanata etc. Maharashtra Lavani, Nakata, Koli, Lezim, Gafa, Dahikala Dashavatar or Bohada, Tamasha, Mouni, Powara, Gauricha etc. Karnataka Yakshagana, huttar, Suggi, Kunitha, Karga, Lambi Gujarat Garba, Dandiya Raas, Tippani Juriun, Bhavai. Punjab Bhangra, Giddha, Daff, Dhaman etc. Rajasthan Ghumar, Chakri, Ganagor, Jhulan Leela, Jhuma, Suisini, Ghapal, Panihari, Ginad etc. Mizoram Khanatm, Pakhupila, Cherokan etc. Jammu Rauf, Hikat, Mandjas, kud Dandi nach, Damali. & Kashmir Tamil Nadu Bharatanatyam, Kummi, Kolattam, Kavadi. Uttar Pradesh Nautanki, Raslila, Kajri, Jhora, Chappeli, Jaita. Bihar Jata-Jatin,Bakho-Bakhain, Panwariya, Sama-Chakwa, Bidesia, Jatra etc. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

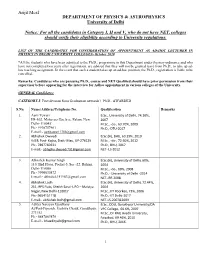

Arijit Mcaf DEPARTMENT of PHYSICS & ASTROPHYSICS

Arijit Mcaf DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS & ASTROPHYSICS University of Delhi Notice: For all the candidates in Category I, II and V, who do not have NET, colleges should verify their eligibility according to University regulations. LIST OF THE CANDIDATES FOR CONSIDERATION OF APPOINTMENT AS AD-HOC LECTURER IN PHYSICS IN DELHI UNIVERSITY COLLEGES- October 2020 *All the students who have been admitted to the Ph.D., programme in this Department under the new ordinance and who have not completed two years after registration, are advised that they will not be granted leave from Ph.D., to take up ad- hoc teaching assignment. In the event that such a student takes up an ad-hoc position, the Ph.D., registration is liable to be cancelled. Remarks: Candidates who are pursuing Ph.D., course and NET Qualified should have prior permission from their supervisor before appearing for the interview for Adhoc appointment in various colleges of the University. GENERAL Candidates: CATEGORY-I: First division from Graduation onwards + Ph.D., AWARDED S.No. Name/Address/Telephone No. Qualification Remarks 1. Aarti Tewari B.Sc., University of Delhi, 74.10%, H4-102, Mahaveer Enclave, Palam, New 2007 Delhi-110045` M.Sc., -do-, 63.70%, 2009 Ph:- 9910757461 Ph.D.,-DTU-2017 E-mail:- [email protected] 2. Abhishek Dwivedi B.Sc.(H), BHU, 60.39%, 2010 Vill & Post- Kajha, Distt- Mau, UP-276129 M.Sc., -do-, 72.60%, 2012 Ph:- 7897760331 Ph.D., BHU, 2017 E-mail:- [email protected] NET- LS-2012 3. Abhishek Kumar Singh B.Sc.(H), University of Delhi, 60%, 110, IInd Floor, Pocket-5, Sec.-22, Rohini, 2004 Delhi-110086 M.Sc., -do-, 60%, 2008 Ph:- 9990030872 Ph.D.,- University of Delhi -2014 E-mail:- [email protected] NET-JRF-2008 4. -

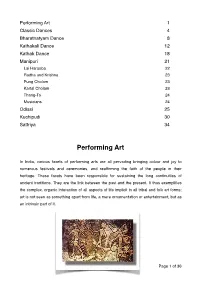

Classical Dances Have Drawn Sustenance

Performing Art 1 Classic Dances 4 Bharatnatyam Dance 8 Kathakali Dance 12 Kathak Dance 18 Manipuri 21 Lai Haraoba 22 Radha and Krishna 23 Pung Cholam 23 Kartal Cholam 23 Thang-Ta 24 Musicians 24 Odissi 25 Kuchipudi 30 Sattriya 34 Performing Art In India, various facets of performing arts are all pervading bringing colour and joy to numerous festivals and ceremonies, and reaffirming the faith of the people in their heritage. These facets have been responsible for sustaining the long continuities of ancient traditions. They are the link between the past and the present. It thus exemplifies the complex, organic interaction of all aspects of life implicit in all tribal and folk art forms; art is not seen as something apart from life, a mere ornamentation or entertainment, but as an intrinsic part of it. Page !1 of !36 Pre-historic Cave painting, Bhimbetka, Madhya Pradesh Under the patronage of Kings and rulers, skilled artisans and entertainers were encouraged to specialize and to refine their skills to greater levels of perfection and sophistication. Gradually, the classical forms of Art evolved for the glory of temple and palace, reaching their zenith around India around 2nd C.E. onwards and under the powerful Gupta empire, when canons of perfection were laid down in detailed treatise - the Natyashastra and the Kamasutra - which are still followed to this day. Through the ages, rival kings and nawabs vied with each other to attract the most renowned artists and performers to their courts. While the classical arts thus became distinct from their folk roots, they were never totally alienated from them, even today there continues a mutually enriching dialogue between tribal and folk forms on the one hand, and classical art on the other; the latter continues to be invigorated by fresh folk forms, while providing them with new thematic content in return. -

Where Now the Harp? Listening for the Sounds of Old English Verse, from Beowulf to the Twentieth Century

Oral Tradition, 24/2 (2009): 485-502 Where Now the Harp? Listening for the Sounds of Old English Verse, from Beowulf to the Twentieth Century Chris Jones nis þær hearpan sweg, / gomen in geardum, swylce ðær iu wæron (2458b-59)1 There is no sound of the harp, delight in courts, as there once were The way to learn the music of verse is to listen to it. (Pound 1951:56) Even within an advanced print culture, poetry arguably never escapes the oral dimension. For Ezra Pound, whose highly intertextual epic The Cantos, so conscious of its page appearance, could only be the product of such a print culture, poetry was nevertheless “an art of pure sound,” the future of which in English was to be the “orchestration” of different European systems of sound-patterning (Pound 1973:33). Verbal orchestration is meaningless without auditors; it goes without saying that the notion of oral literature simultaneously implies the concept of aural literature. This much is also evident from the very beginning of Beowulf: Hwæt, we Gar-Dena in geardagum, / þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon . (“Listen, we have heard of the Spear-Danes in times past, of the glory of the people’s kings . ,” lines 1-2). While the conventionality of the opening might suggest the evocation of a formulaic idiom often associated with oral composition,2 the emphasis is clearly on aurality, on hearing a voice. Much work has been done in recent decades on the evidence in Old English written texts for a poetics that draws on compositional methods derived from an oral culture, either as it had survived into a period of widespread literacy, or as it was imagined to have once existed.3 This essay will not directly address that valuable rehabilitation of oral-formulaic theory into a more sophisticated understanding of early medieval scribal culture, although it will draw on it at times. -

African Language Books for Children: Issues for Authors Viv Edwards University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eCommons@AKU eCommons@AKU Institute for Educational Development, East Africa AKU-East Africa January 2011 African language books for children: issues for authors Viv Edwards University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom Jacob Marriote Ngwaru Aga Khan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.aku.edu/eastafrica_ied Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Edwards, V., Ngwaru, J. M. (2011). African language books for children: issues for authors. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 25(2), 123-137. Available at: http://ecommons.aku.edu/eastafrica_ied/14 Language, Culture and Curriculum ISSN: 0790-8318 (Print) 1747-7573 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rlcc20 African language books for children: issues for authors Viv Edwards & Jacob Marriote Ngwaru To cite this article: Viv Edwards & Jacob Marriote Ngwaru (2012) African language books for children: issues for authors, Language, Culture and Curriculum, 25:2, 123-137, DOI: 10.1080/07908318.2011.629051 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2011.629051 Published online: 25 Oct 2011. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 201 View related articles Citing articles: 5 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rlcc20 Download by: [INASP - Tanzania] Date: 14 February 2017, -

The Development of Literate Potential in Literature-Based and Skills-Based Classrooms Zhihui Fang, University of Florida

The Development of Literate Potential The Development of Literate Potential in Literature-Based and Skills-Based Classrooms Zhihui Fang, University of Florida Abstract This study examined young children’s developing understand- ing of written discourse in two instructional settings: literature-based and skills-based. Forty-one first graders were each requested to dictate two “written” stories for others to read at the beginning and end of the school year. The 82 texts were analyzed for their cohesive harmony, conformity to the socioculturally-codified genre conventions, and use of specific written language features. Quantitative analysis revealed statistically sig- nificant increases in cohesion and genre scores, but only marginal gains in the written language features measures. Further, the development of such written discourse knowledge was not significantly impacted by the instructional context. Qualitative analysis revealed that the children’s texts demonstrated impressive advances in the written mode of organiz- ing and communicating information to others, despite evidence of traces of oral discourse patterns and immature control over diverse genres. These findings are discussed in light of relevant literacy research and practice. Literacy is not a natural outgrowth from orality. Becoming literate in our soci- ety requires that children learn to take control over the written mode of communi- cation. In order to do this, they must come to terms with certain features of written discourse: its sustained organization, its characteristic rhythms and structures, its distinctive grammar, and its disembedded quality (Kress, 1994; Olson & Torrance, 1981; Wood, 1998). While home and community are important to the development of a literate mind, it is the school that is commonly considered the most important site for children’s literacy development.