Re-Appropriated Voices in the Poetry of Kathak Dance Repertoire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

509 Chinthaka Prageeth Meddegoda and Gisa Jähnichen This Co-Written

Book Reviews 509 Chinthaka Prageeth Meddegoda and Gisa Jähnichen, Hindustani Traces in Malay Ghazal: ‘A song, So Old and Yet Still Famous’. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, 386 pp. ISBN 1443897590, price: USD 103.70 (hardcover). This co-written volume aims to study very specific elements of one discrete musical tradition—elements within the Malay ghazal tradition of sung poetry that are directly related to the tradition as practiced in the Hindustani musical world. To address this seemingly modest subject, the book covers an extremely broad range of historical and musicological topics, moving from Persia through various parts of India to the broader Malay world (including Singapore, Suma- tra, and the Riau islands); it discusses the histories of the diverse Indian com- munities in colonial Malaya, and the popularization of ghazal in Lucknow and Johor; and describes the origins of both the Parsi theatre and local Sumatran genre of gamat (the latter genre previously unknown to this reader, a scholar of Sumatran music). To illustrate the challenges and promise of coming to terms with the Malay ghazal, consider that the ghazal seems to have arrived the Malay world at least four different ways: through precolonial Islamic liter- ary circles, the stage productions of the Parsi theatre, the recordings of early Bollywood, and the lived musical experiences of Indians brought to Southeast Asia by the British colonial state (and those who listened to and with them). Consider as well that the ghazal Johor features one musical instrument that comes from the Middle East and uses Arabic musical modes (the gambus), one musical instrument that was brought by Europeans but has been adapted as a substitute for a Hindustani instrument that uses Indian musical modes (the biola, filling in for the sarangi), and one instrument of relatively recent creation that is associated with colonial, Malay, and Indian musical traditions (the har- monium). -

Siddheshwari Devi Final Edit Rev 1

Siddheshwari Devi – The Queen of Thumri1 by Aditi Desai Kashi, Benares or Varanasi; the ancient spiritual centre of Hindustan, famous for its Ganga, its temples and ghats, pandits and pandas, had another more sensual side in its graceful yet throbbing sub-culture of music and dance. There was a time when for every devotee going to a temple to propitiate the gods there was another who, chewing his delicately flavoured paan, 1 Edited, updated and rewritten version based on: Original article written by Aditi Desai for The India Magazine, Aug. 1981, No. 9 would be strolling towards some singer’s or dancer’s house. In the Benares sunset, the sound of temple bells intermingled with the soul stirring sounds of a bhajan, a thumri, a kajri, a chaiti, a hori. And accompanying these were the melodious sounds of the sarangi or flute and the ghunghroos on the beat of the tabla that quickened the heartbeat. So great was the city’s preoccupation with music, that a distinctive style of classical music, rooted in the local folk culture, emerged and was embodied in the Benaras Gharana ( school or a distinctive style of music originating in a family tradition or lineage that can be traced to an instructor or region). A few miles from Benares, there is a village called Torvan, which appears to be like any other Thakur Brahmin village of that region. But there is a difference. This village had a few families belonging to the Gandharva Jati, a group whose traditional occupation was music and its allied arts. Amongst Gandharvas, it was the men who went out to perform while the women stayed behind. -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

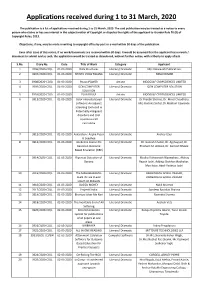

Applications Received During 1 to 31 March, 2020

Applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020 The publication is a list of applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020. The said publication may be treated as a notice to every person who claims or has any interest in the subject matter of Copyright or disputes the rights of the applicant to it under Rule 70 (9) of Copyright Rules, 2013. Objections, if any, may be made in writing to copyright office by post or e-mail within 30 days of the publication. Even after issue of this notice, if no work/documents are received within 30 days, it would be assumed that the applicant has no work / document to submit and as such, the application would be treated as abandoned, without further notice, with a liberty to apply afresh. S.No. Diary No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 3906/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Data Structures Literary/ Dramatic M/s Amaravati Publications 2 3907/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 SHISHU VIKAS YOJANA Literary/ Dramatic NIRAJ KUMAR 3 3908/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 Picaso POWER Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 4 3909/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 ICON COMPUTER Literary/ Dramatic ICON COMPUTER SOLUTION SOLUTION 5 3910/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 PLANOGULF Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 6 3911/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Color intensity based Literary/ Dramatic Dr.Preethi Sharma, Dr. Minal Chaudhary, software: An adjunct Mrs.Ruchika Sinhal, Dr.Madhuri Gawande screening tool used in Potentially malignant disorders and Oral squamous cell carcinoma 7 3912/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Aakarshan : Aapke Pyaar Literary/ Dramatic Akshay Gaur ki Seedhee 8 3913/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Academic course file Literary/ Dramatic Dr. -

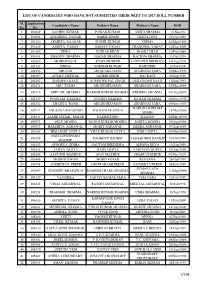

List of Candidates Who Have Not Submitted Their Neet Ug 2017 Roll Number

LIST OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE NOT SUBMITTED THEIR NEET UG 2017 ROLL NUMBER Sl. Application Candidate's Name Father's Name Mother's Name DOB No. No. 1 100249 SACHIN KUMAR PAWAN KUMAR ANITA SHARMA 15.Nov.93 2 100808 ANUSHEEL NAGAR OMBIR SINGH GEETA DEVI 07/Oct/1998 3 101222 AKSHITA DAAGAR SUSHIL KUMAR SEEMA 24/May/1999 4 101469 ANKITA YADAV SANJAY YADAV CHANCHAL YADAV 31/Dec/1999 5 101593 ZEWA NAWAB KHAN NOOR JAHAN 10/Feb/1999 6 101814 SHAGUN SHARMA GAGAN SHARMA RACHNA SHARMA 13/Oct/1998 7 102087 MOHD FAISAL SHAHABUDDIN JANNATUL FIRDOUS 14/Aug/1998 8 102121 SNEHA SOBODH KUMAR RAJENDRI 20/Jul/1998 9 102256 ABUZAR MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 25/Mar/1999 10 102397 ANJALI DESWAL JAGBIR SINGH RAJ RANI 05/Sep/1998 11 102402 RASMEET KAUR SURINDER PAL SINGH GURVINDER KAUR 11/Sep/1997 12 102474 ABU TALHA MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 25/Mar/1999 13 102515 SHIVANI SHARMA RAKESH KUMAR SHARMA KRISHNA SHARMA 01/Aug/2000 14 102529 POONAM SHARMA GOVIND SHARMA RAJESH SHARMA 04/Nov/1998 15 102532 SHAISTA BANO MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 09/Nov/1997 KARUNA KUMARI 16 102711 ANUSHKA RAJ SINGH RAJ KUMAR SINGH 12/Mar/2000 SINGH 17 102841 AAMIR SUHAIL MALIK NASIMUDDIN SHANNO 26/May/1996 18 102971 ABLE MOGHA MANOJ KUMAR MOGHA SARITA MOGHA 19/Aug/1998 19 103053 HARSHITA AGRAWAL MOHIT AGRAWAL MEERA AGRAWAL 07/Sep/1999 20 103245 HIMANSHI GUPTA VIJAY KUMAR GUPTA INDU GUPTA 09/May/2000 NGULLIENTHANG 21 103428 PAOKHUP HAOKIP VANKHOMOI HAOKIP 03/Oct/1998 HAOKIP 22 103433 APOORVA SINHA GAUTAM BIRENDRA ALPANA DEVA 12/Sep/1999 23 103518 TANYA GUPTA RAJIV GUPTA VANDANA GUPTA 29/Apr/1999 -

New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan: Arif Lohar with Arooj Aftab

Asia Society and CaravanSerai Present New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan: Arif Lohar with Arooj Aftab Saturday, April 28, 2012, 8:00 P.M. Asia Society 725 Park Avenue at 70th Street New York City This program is 2 hours with no intermission New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan Performers Arooj Afab lead vocals Bhrigu Sahni acoustic guitar Jorn Bielfeldt percussion Arif Lohar lead vocals/chimta Qamar Abbas dholak Waqas Ali guitar Allah Ditta alghoza Shehzad Azim Ul Hassan dhol Shahid Kamal keyboard Nadeem Ul Hassan percussion/vocals Fozia vocals AROOJ AFTAB Arooj Aftab is a rising Pakistani-American vocalist who interprets mystcal Sufi poems and contemporizes the semi-classical musical traditions of Pakistan and India. Her music is reflective of thumri, a secular South Asian musical style colored by intricate ornamentation and romantic lyrics of love, loss, and longing. Arooj Aftab restyles the traditional music of her heritage for a sound that is minimalistic, contemplative, and delicate—a sound that she calls ―indigenous soul.‖ Accompanying her on guitar is Boston-based Bhrigu Sahni, a frequent collaborator, originally from India, and Jorn Bielfeldt on percussion. Arooj Aftab: vocals Bhrigu Sahni: guitar Jorn Bielfeldt: percussion Semi Classical Music This genre, classified in Pakistan and North India as light classical vocal music. Thumri and ghazal forms are at the core of the genre. Its primary theme is romantic — persuasive wooing, painful jealousy aroused by a philandering lover, pangs of separation, the ache of remembered pleasures, sweet anticipation of reunion, joyful union. Rooted in a sophisticated civilization that drew no line between eroticism and spirituality, this genre asserts a strong feminine identity in folk poetry laden with unabashed sensuality. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

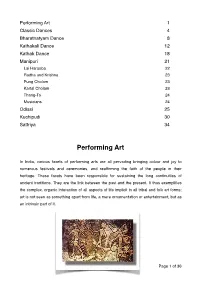

Classical Dances Have Drawn Sustenance

Performing Art 1 Classic Dances 4 Bharatnatyam Dance 8 Kathakali Dance 12 Kathak Dance 18 Manipuri 21 Lai Haraoba 22 Radha and Krishna 23 Pung Cholam 23 Kartal Cholam 23 Thang-Ta 24 Musicians 24 Odissi 25 Kuchipudi 30 Sattriya 34 Performing Art In India, various facets of performing arts are all pervading bringing colour and joy to numerous festivals and ceremonies, and reaffirming the faith of the people in their heritage. These facets have been responsible for sustaining the long continuities of ancient traditions. They are the link between the past and the present. It thus exemplifies the complex, organic interaction of all aspects of life implicit in all tribal and folk art forms; art is not seen as something apart from life, a mere ornamentation or entertainment, but as an intrinsic part of it. Page !1 of !36 Pre-historic Cave painting, Bhimbetka, Madhya Pradesh Under the patronage of Kings and rulers, skilled artisans and entertainers were encouraged to specialize and to refine their skills to greater levels of perfection and sophistication. Gradually, the classical forms of Art evolved for the glory of temple and palace, reaching their zenith around India around 2nd C.E. onwards and under the powerful Gupta empire, when canons of perfection were laid down in detailed treatise - the Natyashastra and the Kamasutra - which are still followed to this day. Through the ages, rival kings and nawabs vied with each other to attract the most renowned artists and performers to their courts. While the classical arts thus became distinct from their folk roots, they were never totally alienated from them, even today there continues a mutually enriching dialogue between tribal and folk forms on the one hand, and classical art on the other; the latter continues to be invigorated by fresh folk forms, while providing them with new thematic content in return. -

Routes 2 Roots Dreams of a Peaceful World Co-Existing with Diverse Cultures, Ruled by Harmony

Routes 2 Roots dreams of a peaceful world co-existing with diverse cultures, ruled by harmony. The world’s largest interactive digital program of teaching performing arts with global reach R-19 LGF, Hauz Khas, New Delhi - 16, Ph: +91 11 41646383 Fax: +91 11 41646384 Studio: Flat No. 5, 1st Floor, Sector - 6 Market, R. K. Puram, New Delhi - 110022, Ph: +91 11 26100114, 26185281 Web: www.routes2roots.com, www.r2rvirsa.in, Email: [email protected] An Initiative of Routes2Roots NGO Routes2Roots twitter.com/Routes2RootsNGO twitter.com/virsar2r virsabyroutes2roots.blogspot.in Board of Advisors & Contributing Maestros of Virsa ROUTES 2 ROOTS Routes 2 Roots is a Delhi based non-profit reputed NGO with a presence all over India. Since its inception in 2004 the NGO is constantly striving to disseminate culture, art and heritage to the common people and the children throughout the world. Ever since its inception in 2004 Routes 2 Roots has dedicated itself to promoting art, culture and heritage throughout the world with the prime objective of spreading the message of peace. We have hosted over 26 international events, 14 exhibitions and 110 concerts throughout the world and all of these programs have been on a non-commercial basis, i.e. no ticketing so that people en masse can come and enjoy a shared experience of each-others’ culture freely. Our organisation is known for quality cultural programs and we have to our credit numerous prestigious international programs such as celebration of 60 years of diplomatic ties between India and China, which was held in 4 cities of China, Celebration of 65 years of Indo-Russian diplomatic ties, which was held in 5 cities of Russia, Festival of India in South Africa covering 4 cities and many more. -

Pandit Ravi Shankar—Tansen of Our Times

Occ AS I ONAL PUBLicATION 47 Pandit Ravi Shankar—Tansen of our Times by S. Kalidas IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE 40, MAX MUELLER MARG , NEW DELH I -110 003 TEL .: 24619431 FAX : 24627751 1 Occ AS I ONAL PUBLicATION 47 Pandit Ravi Shankar—Tansen of our Times The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and not of the India International Centre. The Occasional Publication series is published for the India International Centre by Cmde. (Retd.) R. Datta. Designed and produced by FACET Design. Tel.: 91-11-24616720, 24624336. Pandit Ravi Shankar—Tansen of our Times Pandit Ravi Shankar died a few months ago, just short of his 93rd birthday on 7 April. So it is opportune that we remember a man whom I have rather unabashedly called the Tansen of our times. Pandit Ravi Shankar was easily the greatest musician of our times and his death marks not only the transience of time itself, but it also reminds us of the glory that was his life and the immortality of his legacy. In the passing of Robindro Shaunkar Chowdhury, as he was called by his parents, on 11 December in San Diego, California, we cherish the memory of an extraordinary genius whose life and talent spanned almost the whole of the 20th century. It crossed all continents, it connected several genres of human endeavour, it uplifted countless hearts, minds and souls. Very few Indians epitomized Indian culture in the global imagination as this charismatic Bengali Brahmin, Pandit Ravi Shankar. Born in 1920, Ravi Shankar not only straddled two centuries but also impacted many worlds—the East, the West, the North and the South, the old and the new, the traditional and the modern. -

Bridging the Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances As a Source of Dance/Movement Therapy, a Literature Review

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses (GSASS) Spring 5-16-2020 Bridging The Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review. Ruta Pai Lesley University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses Part of the Art Education Commons, Counseling Commons, Counseling Psychology Commons, Dance Commons, Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pai, Ruta, "Bridging The Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review." (2020). Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses. 234. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses/234 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. BRIDGING THE GAP 1 Bridging the Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review. Capstone Thesis Lesley University August 5, 2019 Ruta Pai Dance/Movement Therapy Meg Chang, EdD, BC-DMT, LCAT BRIDGING THE GAP 2 ABSTRACT Indian Classical Dances are a mirror of the traditional culture in India and therefore the people in India find it easy to connect with them. These dances involve a combination of body movements, gestures and facial expressions to portray certain emotions and feelings. -

Social Attitude Towards Theatre Actresses in 19 Century Bengal

www.ijird.com February, 2016 Vol 5 Issue 3 ISSN 2278 – 0211 (Online) Social Attitude towards Theatre Actresses in 19 th Century Bengal Dr. Sushmita Sengupta Assistant Professor, Department of History, Baruipur College, West Bengal, India Abstract: The 19 th century the ‘age of reasons and reform’ in Bengal saw the question of the theatre actress come to the forefront. With the gradual introduction of the female actress on the stage, they became the figure head on whom the ambivalences and contradictions of the age was manifested. The colonial government had set out to ‘civilize’ the ‘barbaric’ India. The performing artists who had a close association with the courtesan class became the target of the colonizers. Theatre activity was first undertaken by the newly educated Bengali middleclass, who shared the same view of their colonial masters regarding the theatre actresses. The first generation of Bengali actresses remained marginalized in the theatre space. Socially stigmatized and exploited on and off stage, these theatre actresses remained a pawn in the whole set of rules formed by the urban educated middleclass society. Keywords: Reason, reform, theatre, actress, colonial, government, intelligentsia, marginalized. Since time immemorial art and culture has been an inseparable aspect of human life. Art in all its forms has preserved the culture and social system of a particular period or era. The visual arts like “natya” have had a direct contact with the minds of the viewers and the impact of such media on the human mind has been like a photo imprint. So whatever the artist has visually created on the stage has influenced the mind and worked slowly and diligently to change the attitudes and habits of the society.