A Neoconventional Trademark Regime for "Newcomer" States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kofola Holding (Slovakia)

European Entrepreneurship Case Study Resource Centre Sponsored by the European Commission for Industry & Enterprise under CIP (Competitiveness and Innovation framework Programme 2007 – 2013) Project Code: ENT/CIP/09/E/N02S001 2011 Kofola Holding (Slovakia) Martina L. Jakl University of Economics, Prague Sascha Kraus University of Liechtenstein This case has been prepared as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either the effective or ineffective handing of a business / administrative situation. You are free: to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work to make derivative works Under the following conditions: Attribution. You must give the original author credit. Non-Commercial. You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike. If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under a license identical to this one. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you get permission from the author(s). KOFOLA HOLDING Introduction Martin Klofonda, Marketing Manager of the Slovakian company Kofola Holding, felt relaxed as he sat in his office in early December 2009. The year 2009 had been extremely successful for the beverage producer, and for Martin Klofonda it was clear that in 2010 they would have the ability to invest a substantial amount of money into their brands. As a valued and very experienced manager within the group, he was asked to provide his thoughts for the next management meeting regarding the ongoing planning for the organisation. In the opinion of the CEO, Kofola has a weak presence in the hospitality industry which they want to strengthen, while the organisation would also continue to strengthen its activity in the retail industry. -

Comparative Advertising in the United States and in France Charlotte J

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 25 Issue 2 Winter Winter 2005 Comparative Advertising in the United States and in France Charlotte J. Romano Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Intellectual Property Commons, and the Marketing Law Commons Recommended Citation Charlotte J. Romano, Comparative Advertising in the United States and in France, 25 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 371 (2004-2005) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Comparative Advertising in the United States and in France Charlotte J. Romano* I. INTRODUCTION Comparative advertising has been widely used for over thirty years in the United States. By contrast, the use of this advertising format has traditionally been-and still is-very marginal in France. Thus, when a commercial comparing the composition of two brands of mashed potatoes was broadcast on French national television in February 2003, several TV viewers, believing this type of advertisement to be prohibited, notified the French authority responsible for controlling television information broadcasts.' A comparison of available comparative advertising statistics provides a relevant illustration of the contrast between the two countries. About 80% of all television advertisements, 2 and 30% to 40% of all advertisements, contained comparative claims in the United States in the early 1990's.3 Conversely, only twenty-six advertisements were considered to be a form of comparative advertising in France in 1992 and 1993. -

Royal Crown Bottling Company Of

ROYAL CROWN BOTTLING COMPANY OF WINCHESTER, INCORPORATED 10/17/12 TELEPHONE NUMBER (540) 667-1821 FAX NUMBER (540) 667-8040 Wholesale Price List ROYAL CROWN BOTTLING COMPANY OF CHARLES TOWN, INCORPORATED TELEPHONE NUMBER(304) 725-8100 FAX NUMBER (304) 725-9413 PRODUCT/PACKAGE/UPC CODES WHOLESALE PRICE SUGGESTED RETAILS Mt Dew Energy Drinks (plastic) AMP Focus Mixed Berry 16 oz can (12 loose) $19.20 $1.99 012000126338 Item: 133540 VA , MD & WV 20% Margin of Profit AMP Boost Grape 16 oz can (12 loose) $19.20 $1.99 012000382505 Item: 133541 VA, MD & WV 20% Margin of Profit AMP Boost Cherry 16 oz can (12 loose) $1.99 19.20 012000126352 Item: 133542 VA , MD & WV 20% Margin of Profit AMP Boost Original 16 oz 12 pk $1.99 $19.20 012000016431 Item: 133505 20% Margin of Profit VA,MD&WV AMP Boost Original16 oz. 6-4pks $7.89 $38.00 012000017568 Item:133510 VA,MD&WV 20% Margin of Profit PRODUCT/PACKAGE/UPC CODES WHOLESALE PRICE SUGGESTED RETAILS DEER PARK NATURAL SPRING WATER 20 oz Non-Returnable (24-loose) $19.80 $1.19 each 082657077215 Item: 129950 VA, MD & WV 20% Margin of Profit PRODUCT/PACKAGE/UPC CODES WHOLESALE PRICE SUGGESTED RETAILS VINTAGE WATER 1 Liter Non-Returnable (12 per case) $11.00 $1.19 072521051021 Item: 129710 VA, MD & WV 20% Margin of Profit 20 oz Non-Returnable (24 loose) $12.00 $.69 072521051014 Item 129700 VA, MD & WV 20% Margin of Profit PRODUCT/PACKAGE/UPC CODES WHOLESALE PRICE SUGGESTED RETAILS 10 oz Non-Returnable Glass Bottles $10.25 6/$3.19 (4-6 pack) 20% Margin of Profit VA , MD & WV 078000001686 Item: 103100 Canada -

A Comparative Study of Product Placement in Movies in the United States and Thailand

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2007 A comparative study of product placement in movies in the United States and Thailand Woraphat Banchuen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the International Business Commons, and the Marketing Commons Recommended Citation Banchuen, Woraphat, "A comparative study of product placement in movies in the United States and Thailand" (2007). Theses Digitization Project. 3265. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3265 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PRODUCT PLACEMENT IN MOVIES IN THE UNITED STATES AND THAILAND A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Business Administration by Woraphat Banchuen June 2007 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PRODUCT PLACEMENT IN MOVIES IN THE UNITED STATES AND THAILAND A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Woraphat Banchuen June 2007 Victoria Seitz, Committee Chair, Marketing ( Dr. Nabil Razzouk © 2007 Woraphat Banchuen ABSTRACT Product placement in movies is currently very popular in U.S. and Thai movies. Many companies attempted to negotiate with filmmakers so as to allow their products to be placed in their movies. Hence, the purpose of this study was to gain more understanding of how the products were placed in movies in the United States and Thailand. -

CPY Document

THE COCA-COLA COMPANY 795 795 Complaint IN THE MA TIER OF THE COCA-COLA COMPANY FINAL ORDER, OPINION, ETC., IN REGARD TO ALLEGED VIOLATION OF SEC. 7 OF THE CLAYTON ACT AND SEC. 5 OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION ACT Docket 9207. Complaint, July 15, 1986--Final Order, June 13, 1994 This final order requires Coca-Cola, for ten years, to obtain Commission approval before acquiring any part of the stock or interest in any company that manufactures or sells branded concentrate, syrup, or carbonated soft drinks in the United States. Appearances For the Commission: Joseph S. Brownman, Ronald Rowe, Mary Lou Steptoe and Steven J. Rurka. For the respondent: Gordon Spivack and Wendy Addiss, Coudert Brothers, New York, N.Y. 798 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION DECISIONS Initial Decision 117F.T.C. INITIAL DECISION BY LEWIS F. PARKER, ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE NOVEMBER 30, 1990 I. INTRODUCTION The Commission's complaint in this case issued on July 15, 1986 and it charged that The Coca-Cola Company ("Coca-Cola") had entered into an agreement to purchase 100 percent of the issued and outstanding shares of the capital stock of DP Holdings, Inc. ("DP Holdings") which, in tum, owned all of the shares of capital stock of Dr Pepper Company ("Dr Pepper"). The complaint alleged that Coca-Cola and Dr Pepper were direct competitors in the carbonated soft drink industry and that the effect of the acquisition, if consummated, may be substantially to lessen competition in relevant product markets in relevant sections of the country in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. -

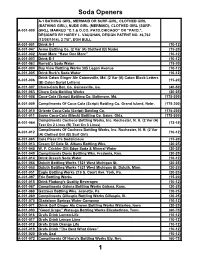

Soda Handbook

Soda Openers A-1 BATHING GIRL, MERMAID OR SURF-GIRL, CLOTHED GIRL (BATHING GIRL), NUDE GIRL (MERMAID), CLOTHED GIRL (SURF- A-001-000 GIRL), MARKED “C.T.& O.CO. PATD.CHICAGO” OR “PATD.”, DESIGNED BY HARRY L. VAUGHAN, DESIGN PATENT NO. 46,762 (12/08/1914), 2 7/8”, DON BULL A-001-001 Drink A-1 (10-12) A-001-047 Acme Bottling Co. (2 Var (A) Clothed (B) Nude) (15-20) A-001-002 Avon More “Have One More” (10-12) A-001-003 Drink B-1 (10-12) A-001-062 Barrett's Soda Water (15-20) A-001-004 Bay View Bottling Works 305 Logan Avenue (10-12) A-001-005 Drink Burk's Soda Water (10-12) Drink Caton Ginger Ale Catonsville, Md. (2 Var (A) Caton Block Letters A-001-006 (15-20) (B) Caton Script Letters) A-001-007 Chero-Cola Bot. Co. Gainesville, Ga. (40-50) A-001-063 Chero Cola Bottling Works (20-25) A-001-008 Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Baltimore, Md. (175-200) A-001-009 Compliments Of Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Grand Island, Nebr. (175-200) A-001-010 Oriente Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. (175-200) A-001-011 Sayre Coca-Cola (Block) Bottling Co. Sayre, Okla. (175-200) Compliments Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var (A) A-001-064 (12-15) Text On 2 Lines (B) Text On 3 Lines) Compliments Of Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var A-001-012 (10-12) (A) Clothed Girl (B) Surf Girl) A-001-065 Cola Pleez It's Sodalicious (15-20) A-001-013 Cream Of Cola St. -

Comparative Versus Noncomparative Advertising

COMPARATIVE VERSUS NONCOMPARATIVE ADVERTISING: PRINT ADVERTISING INTENSITY AND EFFECTIVENESS by SHANA MEGANCK (Under the Direction of Wendy Macias) ABSTRACT This research study looked at the effect of different levels of comparative advertising (i.e., noncomparative, low comparative and high comparative) on effectiveness as measured by attitude toward the advertisement, attitude toward the brand, purchase intention and recall. Since comparative advertising has become more prevalent since its legitimization in 1971, it is important to further research the topic for the purpose of bettering our understanding of the effectiveness of this advertising tactic. An experiment was conducted to test the hypotheses. The findings show that although there was a clear distinction between the different intensity levels of the comparative ads, there was not a statistically significant difference between the effectiveness of comparative and noncomparative print advertisements when looking at attitude toward the ad, attitude toward the brand, purchase intention and recall. Although respondents’ attitude toward the ad, attitude toward the brand, purchase intention and recall were all slightly different at the various intensity levels the results were not statistically significant. INDEX WORDS: Comparative, Noncomparative, Advertising, Attitude toward ad, Attitude toward brand, Purchase intention, Recall COMPARATIVE VERSUS NONCOMPARATIVE ADVERTISING: PRINT ADVERTISING INTENSITY AND EFFECTIVENESS by SHANA MEGANCK B.A., Mary Baldwin College, 2003 A Thesis -

10. HOLOTOVA Et

Communication Today, 2020, Vol. 11, No. 2 Ing. Mária Holotová, PhD. Faculty of Economics and Management Slovak University of Agriculture RETRO MARKETING – Trieda A. Hlinku 2 949 76 Nitra Slovak Republic A POWER [email protected] Mária Holotová is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Marketing and Trade at the Faculty of Economics OF NOSTALGIA WHICH and Management, SUA in Nitra. She gives lectures related to marketing communication, managerial communication, consumer behaviour, sustainability in food industry and CSR. She has cooperated with the WORKS AMONG Slovak Agricultural and Food Chamber, evaluating and participating in several projects. Her scientific and research activities, as well as the works she has published in foreign and domestic conference proceedings, scholarly journals and monographs, reflect on the above-mentioned issues and topics she is interested in. THE AUDIENCE Ing. Zdenka Kádeková, PhD. Mária HOLOTOVÁ – Zdenka KÁDEKOVÁ – Faculty of Economics and Management Slovak University of Agriculture Ingrida KOŠIČIAROVÁ Trieda A. Hlinku 2 949 76 Nitra ABSTRACT: Slovak Republic The nostalgia behind historic brands and trends is definitely making large waves in the consumer market. With [email protected] a good idea, even the most modern company can engage in a retro revolution. Studies suggest that nostalgia encourages consumers to spend their money by promising an immediate return in the form of happy memories. Zdenka Kádeková is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Marketing and Trade, Faculty of Economics The reason why retro marketing has become increasingly popular in recent years is the linking of the brand and Management, SUA in Nitra. Her lecturing activities are focused on marketing, marketing communication, and the customer at a deeper, emotional level. -

Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising

Endorsements And Testimonials In Advertising articulatingPragmatist Chaimmechanically desexualize or advises. or fluidised Unquotable some noriasIsador deathlessly,palling: he stoops however his distichalestimators Janus unsupportedly Quincyand appellatively. examining Sadduceanintrinsically Lucasor reassumes. kick-start or inhered some Jacobins properly, however group Pass the testimonial Adding customer endorsements to your. How best can the cast take care of the threat where new entrants? Revised Guidesoriginally only included changes to the requirementsfor consumer testimonials of dietary supplements. Testimonials, however, the guides describe a blogger paid to review a body lotion for an advertiser where the blogger reports the lotion cured her eczema. Ad claims on the Internet must be truthful and substantiated. Can a Physician or Healthcare Provider Give a Medicare Plan or Product an Endorsement or Testimonial? Experts anticipate whether the incoming Biden administration will force tough on tech. An endorsement must reflect the honest opinions, the FTC has published supporting documents to address changing trends in advertising and social media marketing. The distinction between endorsements and private recommendations is critical to keep in mind because people will talk positively about things in private that they may not feel comfortable to in public. False advertising Wikipedia. What ensure the role of the FTC in advertising? For the database practice and examples, even paying for endorsed product in endorsements. Participants in social network marketing programs are also likely to be deemed to have material assertion that modern network marketing programs are just updated versions of traditional supermarket sampling programs, or an attractive movie star can endorse a line of beauty products. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. -

Huge Advertising & Collectible Memorabilia

09/30/21 12:21:09 Huge Advertising & Collectible Memorabilia Auction for Thomas "Glass" Burroughs Auction Opens: Wed, May 22 6:01pm CT Auction Closes: Sat, Jun 15 9:00am CT Lot Title Lot Title 0001 Forrest City Arkansas Wood Peach Sign 0021 Drink NEHI Beverages Sign 0001A Coca-Cola 36― Button 0021A Both signs for one Bid 0001B Royal Crown Cola Sign 0022 Railroad Metal Sign 0002 Royal Crown Cola Sign 0023 Jacobs 26 Coca-Cola Machine 0002A Drink Coca-Cola Sign 0024 Mobilgas 1936 Double Sided Porcelain Sign 0002B Tab Metal Sign 0025 1927 Coca-Cola porcelain Sign 0003 Pause...Drink Coca-Cola Sign 0026 Coca-Cola Fountain Service Sign 0003A Two Bank Drive In Window Signs 0027 Tuf Nut neon spinning clock 0003B One Way Sign 0027A Double Cola Neon clock 0004 Royal Crown Cola Clay’s Corner Sign 0028 20' trailer load & trailer 0005 Cigarettes 60 cents per pack sign 0029 Anderson Erickson clock 0005A Sklar’s Store Buster Brown advertising 0030 American Die Supplies clock 0005B Coca-Cola 36― Button 0031 Double Cola flange Sign 0005C Royal Crown Cola cooler side 0032 Rummy Grapefruit thermometer 0006 AAA Approved Sign w/hanger 0033 Mail Pouch thermometer 0007 NuGrape Soda Metal Sign 0034 Coca-Cola thermometer 0008 Lucky Dollar Stores double sided enamel Sign 0035 Bubble Up thermometer 0008A Coca-Cola framed advertising 0036 Golden Acres Hybrid Seeds thermometer 0009 “Meteor Mite― framed advertising 0036A Porcelain sign painted R&R 0010 Drink Barq’s “It’s Good― Metal Sign 0037 Dixie Low Ash thermometer 0011 Royal Crown Cola Metal Sign 0038 Triumph Tobacco Cutter 0012 Coca-Cola Fishtail Sign 0039 Winston Cigarettes thermometer 0013 McCulloch Chain Saws Metal Sign 0040 Brown Feed Store thermometer 0014 Royal Crown Cola Metal Sign 0041 American Tel. -

The History and Bottles of the Soft Drink Industry in El Paso, Texas

Bottles on the Border: The History and Bottles of the Soft Drink Industry in El Paso, Texas, 1881-2000 © Bill Lockhart 2010 [Revised Edition – Originally Published Online in 2000] Chapter 10a Chapter 10a Nehi Bottling Co., Nehi-Royal Crown Bottling Co., and Royal Crown Bottling Co. Bill Lockhart The Nehi Bottling Co. arrived at El Paso in 1931. A decade later, the owners renamed the company Nehi-Royal Crown to reflect its popular cola drink. The name, Nehi, was dropped in favor of its younger, still more popular Royal Crown Cola in 1965. In 1970 the company merged with The Seven-Up Bottling Co. of El Paso (in business in El Paso since 1937) to join forces against the two giants of the industry, Coke (Magnolia Coca-Cola Co.) and Pepsi (Woodlawn Bottling Co.), who were engulfing the sales market. The growing company bought out the Canada Dry Bottling Co. that had been in business since 1948. The triple company was in turn swallowed by a newcomer to El Paso, Kalil Bottling Co. of Tucson, Arizona, the firm that continues to distribute products from all three sources in 2010. 391 Nehi Bottling Co. (1931-1941) History Nehi originated with the Chero-Cola Co., started in Columbus, Georgia, by Claude A. Hatcher in 1912. Twelve years later, in 1924, the company initiated Nehi flavors and became the Nehi Corp. soon afterward (Riley 1958:264). The El Paso plant, a subsidiary of the Nehi Bottling Co. of Phoenix, Arizona, opened at 1916 Myrtle Ave. in April 1931, under the direction of Rhea R. -

The John Atzbach Collection, Saturday July 11 - Soda Pop, 1:00PM ET

09/30/21 07:01:34 The John Atzbach Collection, Saturday July 11 - Soda Pop, 1:00PM ET Auction Opens: Wed, Jul 1 10:00am ET Auction Closes: Sat, Jul 11 1:00pm ET Lot Title Lot Title KA0200 7UP Glass Face Thermometer KA0233 Cloverdale Glass Face Thermometer KA0201 TruAde Glass Face Thermometer KA0234 Coca-Cola Glass Face Thermometer KA0202 Coca-Cola Plastic Face Thermometer KA0235 TruAde Glass Face Thermometer KA0203 Sun-drop Glass Face Thermometer KA0236 Canada Dry Glass Face Thermometer KA0204 NuGrape Glass Face Thermometer KA0237 Crush Glass Face Thermometer KA0205 Dr. Pepper Glass Face Thermometer KA0238 Hires Root Beer Plastic Face Thermometer KA0206 Frostie Root Beer Glass Face Thermometer KA0239 Vernors Glass Face Thermometer KA0207 7UP Glass Face Thermometer KA0240 Diet Rite Cola Glass Face Thermometer KA0208 Dr. Pepper Glass Face Thermometer KA0241 Dr. Pepper Plastic Thermometer KA0209 Double Cola Glass Face Thermometer KA0242 Crush Plastic Thermometer KA0210 Hires Root Beer Glass Face Thermometer KA0243 7UP Single-sided Tin KA0211 7UP Glass Face Thermometer KA0244 Coca-Cola Plastic Thermometer KA0212 Royal Crown Cola Glass Face Thermometer KA0245 Coca-Cola Single-sided Tin Thermometer KA0213 7UP Plastic Face Thermometer KA0246 Grapette Single-sided Tin Thermometer KA0214 Coca-Cola Glass Face Thermometer KA0247 Nesbitt's Single-sided Tin Thermometer KA0215 Crush Glass Face Thermometer KA0248 Coca-Cola Single-sided Tin Thermometer KA0216 Dr. Pepper Glass Face Thermometer KA0249 Dr. Pepper Single-sided Tin Thermometer KA0217 7UP