Classics 2: Celebrating Greatness Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Johann Strauss: "Die Fledermaus"

JOHANN STRAUSS DIE FLEDERMAUS Operette in drei Aufzügen Eine Veranstaltung des Departments für Musiktheater in Kooperation mit den Departments für Gesang, Bühnenbild- und Kostümgestaltung, Film- und Ausstellungsarchitektur sowie Schauspiel/Regie – Thomas Bernhard Institut Mittwoch, 2. Dezember 2015 Donnerstag, 3. Dezember 2015 Freitag, 4. Dezember 2015 19.00 Uhr Samstag, 5. Dezember 2015 17.00 Uhr Großes Studio Universität Mozarteum Mirabellplatz 1 Besetzung 2.12. / 4.12. 3.12. / 5.12. Musikalische Leitung Kai Röhrig Szenische Leitung Karoline Gruber Gabriel von Eisenstein, Notar Markus Ennsthaller Michael Etzel Bachelor Gesang, 3. Semester Bachelor Gesang, 7. Semester Bühne Anna Brandstätter / Christina Pointner Kostüme Iris Jedamski Rosalinde, seine Frau Sassaya Chavalit Julia Rath Master Musiktheater, 3. Semester Master Musiktheater, 3. Semester Regieassistenz Agnieszka Lis Orlofsky Alice Hoffmann Reba Evans Dramaturgie Ronny Dietrich Master Gesang, 3. Semester Master Musiktheater, 1. Semester Dialogarbeit Ulrike Arp Dr. Falke, Notar Thomas Hansen Darian Worrell Licht Christina Pointner / Anna Ramsauer Master Musiktheater, 3. Semester Master Musiktheater, 1. Semester Musikalische Einstudierung Lenka Hebr, Dariusz Burnecki, Andrea Strobl Alfred, Gesangslehrer Thomas Huber Jungyun Kim Musikalische Assistenz Wolfgang Niessner Master Gesang, 3. Semester Master Musiktheater, 3. Semester Technische Leitung Andreas Greiml, Thomas Hofmüller Frank, Gefängnisdirektor Felix Mischitz Felix Mischitz Bühnen-, Beleuchtungs-, Michael Becke, Sebastian Brandstätter, Markus Ertl, Bachelor Gesang, 5. Semester Bachelor Gesang, 5. Semester Tontechnik und Werkstätten Rafael Fellner, Sybille Götz, Markus Graf, Peter Hawlik, Alexander Lährm, Anna Ramsauer, Elena Wagner Adele, Kammermädchen Jennie Lomm Claire Austin Salonorchester der Universität Mozarteum Master Musiktheater, 3. Semester Master Musiktheater, 3. Semester Violine 1 Kamille Kubiliute Ida, ihre Schwester Domenica Radlmaier Sarah Bröter Violine 2 Elia Antunez Bachelor Gesang, 9. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

900326-CD-Franz Von Suppe-Ouvertueren Itunes.Indd

Franz von Suppé OUVERTÜREN IVAN REPUŠIC´ MÜNCHNER RUNDFUNKORCHESTER FRANZ VON SUPPÉ 1819–1895 OUVERTÜREN 01 Die schöne Galathée 7:21 02 Dichter und Bauer 9:14 03 Boccaccio 7:17 04 Leichte Kavallerie 6:41 05 Banditenstreiche 6:19 06 Pique Dame 7:19 07 Die Frau Meisterin 7:11 08 Ein Morgen, ein Mittag, ein Abend in Wien 8:07 Total time 59:29 Münchner Rundfunkorchester Ivan Repušic´ Dirigent / conductor Studio-Aufnahme / Studio-Recording: München, Bayerischer Rundfunk, Studio 1, 02.–05. Mai 2018 Executive Producer: Veronika Weber und Ulrich Pluta Tonmeister / Recording Producer: Torsten Schreier Toningenieur / Balance Engineer: Klemens Kamp Mastering Engineer: Christoph Stickel Publisher © Carl Musikverlag, Kalmus, Kistner & Siegel, Musikverlag Matzi, Wien Fotos / Photography: Ivan Repušic´ © BR / Lisa Hinder; Franz von Suppé © Ignaz Eigner; Münchner Rundfunkorchester © Felix Broede Design / Artwork: Barbara Huber, CC.CONSTRUCT Editorial: Thomas Becker Lektorat: Dr. Doris Sennefelder Eine CD-Produktion der BRmedia Service GmbH. P + © 2018 BRmedia Service GmbH FRANZ VON SUPPÉ – OUVERTÜREN Konservatorium der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde bei Simon Sechter und Ignaz von Seyfried, einem Freund Ludwig van Beethovens, studierte. Mit Franz von Suppé – sein Name ist dem Publikum der sogenannten Leich- dem Manuskript der am 13. September 1835, unmittelbar nach seiner Abreise ten Klassik wohlbekannt; einige seiner Melodien mag manch einer aus Dalmatien, in der Franziskus-Kirche in Zara uraufgeführten Messe für auf Anhieb anstimmen können – mitpfeifen kann sie jedes Kind. Titel Männerstimmen und Orgel, die er nach dem Tod des Vaters vollendet hatte, wie Leichte Kavallerie, Dichter und Bauer oder Ein Morgen, ein Mittag, überzeugte er Seyfried, ihn als Schüler anzunehmen. -

Österreich (PDF, 342KB)

Österreich Bitte beachten Sie, dass zu den ab Seite 48 genannten Filmtiteln im Bundesarchiv kein benutzbares Material vorliegt. Gern können Sie unter [email protected] erfragen, ob eine Nutzung mittlerweile möglich ist. - Bleriot‘s Flug in Wien (1909) - Aus alten Wochenberichten (1910/15) ...Stadtbilder von Wien. Blick auf die Hofburg. Großer Platz. Paradeaufstellung. Kaiser Franz Josef und Gefolge schreiten die Front ab. - Die Hochzeit in Schwarzau (1911) Hochzeit des Erzherzogs Karl Franz Joseph mit der Prinzessin Zita von Bourbon-Parma auf Schloß Parma in Schwarzau/Niederösterreich am 21.11.1911. - Eine Fahrt durch Wien (ca. 1912/13) Straßenbahnfahrt über die Ringstraße (Burgtheater, Oper) - Gaumont-Woche – Einzelsujets (1913) ...Wien: Reitertruppe kommt aus der Hofburg. - Gaumont-Woche – Einzelsujet: Militärfeier anläßlich des 100. Jahrestages der Schlacht bei Leipzig (1913) (aus Gaumont-Woche 44/1913) ...angetretene Militärformationen, Kavallerie-Formamation. Marsch durch die Straßen der Stadt Wien, am Straßenrand Uniformierte mit auf die Straße. Gesenkten Standarten. Kaiser Franz Joseph und ein ihn begleitender Offizier grüßen die angetretenen Forma- tionen. Beide besteigen eine Kutsche und fahren ab. ( 65 m) - 25 Jahre Zeppelin-Luftschiffahrt (ca. 1925) - Himmelstürmer (1941) ...Luftschiff „Sachsen“ auf der Fahrt nach Wien 1913. Landung auf dem Flugplatz Aspern - Der eiserne Hindenburg in Krieg und Frieden ...Extraausgabe des „Wiener Montag“ mit der Schlagzeile: Der Thronfolger ermordet - Eiko-Woche (1914) ...Erzherzog -

Juncker Ist Neuer EU- Kommissionspräsident

Ausg. Nr. 133 • 4. August 2014 Unparteiisches, unabhängiges Monats- magazin speziell für Österreicherinnen und Österreicher in aller Welt in vier verschiedenen pdf-Formaten http://www.oesterreichjournal.at Juncker ist neuer EU- Kommissionspräsident Das Europäische Parlament hat Jean-Claude Juncker am 15. Juli mit einer starken Mehrheit von 422 Stimmen zum neuen Präsidenten der Europäischen Kommission gewählt. © 2014 European Parliament Jean-Claude Juncker ist der erste demokratisch gewählte Präsident der EU-Kommission. or der Abstimmung im Plenum des Eu- den ersten drei Monaten meiner Amtszeit, migkeiten als Kandidat für das Amt des Prä- Vropäischen Parlaments stellte Juncker ein Paket für Arbeitsplätze, Wachstum und sidenten der Europäischen Kommission vor- in einer Rede seine politischen Leitlinien Investition vorlegen, um 300 Milliarden geschlagen wurde, benötigte er eine Mehr- vor: „Meine erste Priorität und der Leitfaden Euro an Investitionen über die kommenden heit von 376 der insgesamt 751 Stimmen im jeden einzelnen Vorschlages ist Wachstum drei Jahre zu generieren.“ Europaparlament – die er mit 422 Stimmen und Arbeitsplätze in Europa zu schaffen“, Nachdem Juncker vom Europäischen Rat schließlich erreicht hatte. sagte er. „Um das zu erreichen werde ich, in am 27. Juni 2014 nach einigen Mißstim- Lesen Sie weiter auf der Seite 3 ¾ Sie sehen hier die Variante A4 mit 72 dpi und geringer Qualität von Bildern und Grafiken ÖSTERREICH JOURNAL NR. 133 / 04. 08. 2014 2 Die Seite 2 Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, diesmal erwarten Sie leider gleich vier Nachrufe: auf die erst am 2. August verstorbene Nationalratspräsidentin Barbara Prammer, auf die Schauspieler Gert Voss und Dietmar Schönherr sowie auf den Physiker Heinz Zemanek, Erbauer des »Mailüfterls« – einer der welt- weit ersten Computer, die mit Hilfe von Transistoren funktionierten. -

|What to Expect from Così Fan Tutte

| WHAT TO EXPECT FROM COSÌ FAN TUTTE ON THE SURFACE, MOZART’S COSÌ FAN TUTTE HAS ALL THE MARKINGS OF THE WORK: a typical comic opera: tender lovers, a crafty maidservant, deceptions and COSÌ FAN TUTTE pranks, trials and confessions, and a wedding at the conclusion. But on closer An opera in two acts, sung in Italian study, Così fan tutte is a paradox. It explores depths of emotion previously Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart untapped in opera buffa while moving between high farce and profound Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte beauty. That the work could be both accused of irony, cynicism, and triviality First performed January 26, 1790 and celebrated for communicating deep emotional truth and philosophical at the Burgtheater, Vienna, Austria import is a testament to this opera’s complex identity. Written barely two years before Mozart’s early death, Così fan tutte stands as his final, multi- PRODUCTION layered statement in the Italian opera buffa genre. Amid the opera’s quick-fire David Robertson, Conductor comedy and ravishing melodies, the drama offers an examination of the battle Phelim McDermott, Production between love and reason and a closer understanding of human fallibility. Tom Pye, Set Designer This new Met production, previously presented at the English National Opera, is by the inventive director Phelim McDermott, whose work in opera Laura Hopkins, Costume Designer ranges from Philip Glass’s Satyagraha to The Enchanted Island, an original Paule Constable, Lighting Designer Baroque pastiche opera. In Così fan tutte, McDermott transforms the opera’s original setting but maintains its characters’ isolation: The drama unfolds STARRING in a surprisingly closed environment in which the characters’ only seeming Amanda Majeski occupation is the business of love. -

Johann Strauss II's Die Fledermaus: Historical Background and Conductor's Guide

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 2019 Johann Strauss II's Die Fledermaus: Historical Background and Conductor's Guide Jennifer Bruton University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Bruton, Jennifer, "Johann Strauss II's Die Fledermaus: Historical Background and Conductor's Guide" (2019). Dissertations. 1727. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1727 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHANN STRAUSS II’S DIE FLEDERMAUS: HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE by Jennifer Jill Bruton A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Music at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved by: Dr. Jay Dean, Committee Chair Dr. Joseph Brumbeloe Dr. Gregory Fuller Dr. Christopher Goertzen Dr. Michael A. Miles ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Jay Dean Dr. Jay Dean Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Director of School Dean of the Graduate School December 2019 COPYRIGHT BY Jennifer Jill Bruton 2019 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT Students pursuing graduate degrees in conducting often have aspirations of being high school or college choir or band directors. Others want to lead orchestra programs in educational or professional settings. Sadly, many colleges and universities do not have systems in place that provide avenues for those choosing this career path. -

What Did Women Sing? a Chronology Concerning Female Choristers Laura Stanfield Prichard Northeastern University, Massachusetts, USA

What Did Women Sing? A Chronology concerning Female Choristers Laura Stanfield Prichard Northeastern University, Massachusetts, USA Women have been professional soloists throughout the history of church and dramatic music, but have not always participated in choral singing. This paper explores the roots of women as equal partners in mixed choral music, and brings to light several historical moments when women “broke through” older prejudices and laid the groundwork for the modern mixed chorus. The Early Church In ancient Egypt, music was under the patronage of male gods. Osiris was said to have traveled to Ethiopia, where he heard a troupe of traveling satyrs who performed with nine musical maidens, perhaps the prototype of the Grecian muses. Since ancient Greek poetry and music were inseparable, there are many examples of female performers ranging from the mythological (the Muses and the Sirens) to slave girls and the lyric poet Sappho (c630-570 BCE). Antiphonal religious singing came from Jewish temple practice and was introduced to Christian gnostic worship by Bardesanes (154-222 CE) in Persia, who composed psalms and hymns for the Edessa congregation (in imitation of David’s Psalter). The early Catholic Church found it necessary to confront and reinterpret this movement, which spread from Persia into Antioch and thence through the Orient. The Synod of Antioch in 379 specified that men and women could not combine together on the same melody, so most congregations were divided into two demi- choruses, one of men, the other of women and children, each delivering a verse of the psalm then uniting for refrains only rarely. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 11, 1891-1892

4®h TUB National Conservatory of music OF AMERICA. 126 and 128 East 17th Street, New York. [Incorporated September 21, 18S5.] OFFICERS. Pres. Mrs. JEANNETTE M. THURBER. Treas. RICHARD IRVIN, Jr. Secretary, CHAS. INSLEE PARDEE, A.M. Founded for the benefit of Musical Talent in the United States, and conferring its benefits free upon all applicants sufficiently gifted to warrant the prosecution of a thorough course of studies, and unable to pay for the same, and upon others of the requisite aptitude on the payment of a small fee. FACULTY. Dr. ANTONIN DVORAK Has been engaged as Director, and will enter upon his duties September 23, 1892. SlNGIN*G. Principal of Vocal Department— Mr. R. Sapio. Mr. Christian Fritsch. Miss Katharine W. Evans. Mme. Elena Corani. Mr. Oscar Saenger. Mr. Wilfred Watters. Mr. R. Sapio. Opera Class — Herr Emil Fischer. Oratorio Class — Mrs. Beebe Lawton. Ensemble and Operatic Chorus — To be selected. Piano. Mr. Rafael Joseffy. Miss Adele Margulies. Miss Elinor Comstock. Mr. Leopold Winkler. Mrs. Jessie Pitmey Baldwin. Miss Mabel Prnpps. Mr. J. G. Huneker. Organ — Mr. Samuel P. Warren. Harp — Mr. John Cheshire. Violin. Mme. Camilla Urso. Mr. Leopold Lichtenberg. Mr. Jan Koert. Mr. Juan Buitrago. Viola — Mr. Jan Koert. Violoncello — Mr. Victor Herbert, Mr. Emile Knell. Contrabass — Mr. Ludwig Manoly. Flute — Mr. Otto Oesterle. Oboe — Mr. Arthur Trepte. Clarinet — Mr. Richard Kohl. Bassoon — Mr. Adolph Sohst. Cornet — Mr. Carl Sohst. French Horn — Mr. Carl Pieper. Harmony, Counterpoint, and Composition. Mr. Bruno Oscar Klein. Mr. F. Q. Dulcken. Solfeggio — Mr. John Zobanaky, Miss Leila La Fetra. Chamber Music—Mr. -

Franz Von Suppé

La compagnia presenta Boccaccio Operetta in tre atti in lingua tedesca Musiche di Franz von Suppé ASCONA ERSTFELD LUGANO-PARADISO Teatro del Gatto Theater Casino Sala multiuso Paradiso 15 + 16 aprile 2016, ore 20.30 23. April 2016, 19.00 Uhr 4 maggio 2016, ore 20.30 17 aprile 2016, ore 15.30 24. April 2016, 15.00 Uhr 5 maggio 2016, ore 15.30 [email protected] www.ilpalco.ch HINWEISE / INFORMAZIONI Einzeleintritt / Entrata fr. 29.– Gruppen ab 10 Personen / Gruppi da 10 persone e carta cantonale per studenti fr. 25.– p.p. VORVERKAUF / PREVENDITA: Ascona: Teatro il Gatto Tel. 091 792 21 21 Erstfeld: Druckerei Gasser Tel. 041 880 10 30 Lugano-Paradiso: Team il Palco Tel. 077 434 62 90 Die Kasse ist eine Stunde vor Vorstellungsbeginn geöff net. Reservierte Billette bitte 20 Min. vorher abholen. La cassa verrà aperta un’ora prima dello spettacolo. Per favore ritirare i biglietti pre- notati 20 minuti prima dell’inizio. Dauer der Aufführung: inklusive Pause nach dem 1. Akt. ca. 2½ Stunden. Durata dello spettacolo: inclusa pausa dopo il primo atto, circa 2½ ore. Fahrplan: Rückreisen in alle Richtungen mit den öffentlichen Verkehrsmitteln gewähr- leistet. Orario: Garantita la possibilità di ritorno con i mezzi pubblici in tutte le direzioni Info: 077 434 62 90, [email protected] HÄTTEN SIE LUST UND ZEIT EINMAL IN EINER THEATERPRODUKTION MITZUWIRKEN? Wir suchen für die nächste Produktion interessierte Damen und Herren mit oder ohne Bühnenerfahrung, die gerne singen, spielen und natürlich eine Rolle verkörpern wollen. Wenn dies zutrifft, dann melden Sie sich bei uns: telefonisch, schriftlich oder mit einem E-Mail. -

Untitled, It Is Impossible to Know

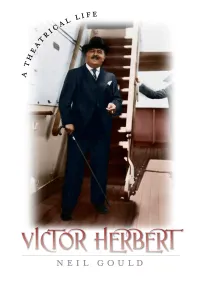

VICTOR HERBERT ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE i ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE ii VICTOR HERBERT A Theatrical Life C:>A<DJA9 C:>A<DJA9 ;DG9=6BJC>K:GH>INEG:HH New York ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iii Copyright ᭧ 2008 Neil Gould All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gould, Neil, 1943– Victor Herbert : a theatrical life / Neil Gould.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2871-3 (cloth) 1. Herbert, Victor, 1859–1924. 2. Composers—United States—Biography. I. Title. ML410.H52G68 2008 780.92—dc22 [B] 2008003059 Printed in the United States of America First edition Quotation from H. L. Mencken reprinted by permission of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore, Maryland, in accordance with the terms of Mr. Mencken’s bequest. Quotations from ‘‘Yesterthoughts,’’ the reminiscences of Frederick Stahlberg, by kind permission of the Trustees of Yale University. Quotations from Victor Herbert—Lee and J.J. Shubert correspondence, courtesy of Shubert Archive, N.Y. ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iv ‘‘Crazy’’ John Baldwin, Teacher, Mentor, Friend Herbert P. Jacoby, Esq., Almus pater ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE v ................ -

IAWM Article for My Website.Cwk (WP)

Criseyde – A Feminist Opera by Alice Shields In 2006 Nancy Dean, former professor of medieval studies at Hunter College and medievalist specializing in Chaucer, commissioned me to write an opera based on Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, one of the greatest of the medieval romances. A similar story was told earlier by Boccaccio, and later by Shakespeare. It is a tale of love and supposed betrayal that takes place during the Trojan War between Troy and Greece. My opera Criseyde is in two acts, for five solo singers, ensemble of three singers, and fourteen instruments, and is two hours long. The roles are: Criseyde, a young widow, a noble lady of Troy (soprano); Troilus, Prince of Troy (lyric baritone), Cassandra, a psychic oracle, sister to Troilus (mezzo-soprano); Pandar, uncle to Criseyde and subordinate of Troilus (basso cantante), who also plays Calkas, the father of Criseyde; and Diomede, a Greek prince (baritone). The Three Ladies, who sing as an ensemble, are nieces and companions to Criseyde (soprano and two mezzo-sopranos). The orchestra consists of flute/piccolo, oboe, english horn, bassoon, horn, trumpet, trombone, harp, piano, violin 1, violin 2, viola, cello, and contrabass. For those who need a quick refresher, I am providing just the bare outline of Chaucer's plot. Troilus falls in love with Criseyde (Cressida). Her uncle, Pandar, who in the absence of her father controls her economically and socially, forces her to let his boss Troilus visit her. Despite her misgivings, she falls deeply in love with him. They consummate their love and vow to be true to each other in a secret relationship, but soon the parliament of Troy decides to exchange Criseyde for a valuable Trojan prisoner held by the Greeks.