Cicero, on Pompey's Command (De Imperio), 27–49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pompey, the Great Husband

Michael Jaffee Patterson Independent Project 2/1/13 Pompey, the Great Husband Abstract: Pompey the Great’s traditional narrative of one-dimensionally striving for power ignores the possibility of the affairs of his private life influencing the actions of his political career. This paper gives emphasis to Pompey’s familial relationships as a motivating factor beyond raw ambition to establish a non-teleological history to explain the events of his life. Most notably, Pompey’s opposition to the special command of the Lex Gabinia emphasizes the incompatibility for success in both the public and private life and Pompey’s preference for the later. Pompey’s disposition for devotion and care permeates the boundary between the public and private to reveal that the happenings of his life outside the forum defined his actions within. 1 “Pompey was free from almost every fault, unless it be considered one of the greatest faults for a man to chafe at seeing anyone his equal in dignity in a free state, the mistress of the world, where he should justly regard all citizens as his equals,” (Velleius Historiae Romanae 2.29.4). The annals of history have not been kind to Pompey. Characterized by the unbridled ambition attributed as his impetus for pursuing the civil war, Pompey is one of history’s most one-dimensional characters. This teleological explanation of Pompey’s history oversimplifies the entirety of his life as solely motivated by a desire to dominate the Roman state. However, a closer examination of the events surrounding the passage of the Lex Gabinia contradicts this traditional portrayal. -

Valerius Maximus on Vice: a Commentary of Facta Et Dicta

Valerius Maximus on Vice: A Commentary on Facta et Dicta Memorabilia 9.1-11 Jeffrey Murray University of Cape Town Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the School of Languages and Literatures University of Cape Town June 2016 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Abstract The Facta et Dicta Memorabilia of Valerius Maximus, written during the formative stages of the Roman imperial system, survives as a near unique instance of an entire work composed in the genre of Latin exemplary literature. By providing the first detailed historical and historiographical commentary on Book 9 of this prose text – a section of the work dealing principally with vice and immorality – this thesis examines how an author employs material predominantly from the earlier, Republican, period in order to validate the value system which the Romans believed was the basis of their world domination and to justify the reign of the Julio-Claudian family. By detailed analysis of the sources of Valerius’ material, of the way he transforms it within his chosen genre, and of how he frames his exempla, this thesis illuminates the contribution of an often overlooked author to the historiography of the Roman Empire. -

295 Emanuela Borgia (Rome) CILICIA and the ROMAN EMPIRE

EMANUELA BORGIA, CILICIA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 16/2017 ISSN 2082-5951 DOI 10.14746/seg.2017.16.15 Emanuela Borgia (Rome) CILICIA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE: REFLECTIONS ON PROVINCIA CILICIA AND ITS ROMANISATION Abstract This paper aims at the study of the Roman province of Cilicia, whose formation process was quite long (from the 1st century BC to 72 AD) and complicated by various events. Firstly, it will focus on a more precise determination of the geographic limits of the region, which are not clear and quite ambiguous in the ancient sources. Secondly, the author will thoroughly analyze the formation of the province itself and its progressive Romanization. Finally, political organization of Cilicia within the Roman empire in its different forms throughout time will be taken into account. Key words Cilicia, provincia Cilicia, Roman empire, Romanization, client kings 295 STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 16/2017 · ROME AND THE PROVINCES Quos timuit superat, quos superavit amat (Rut. Nam., De Reditu suo, I, 72) This paper attempts a systematic approach to the study of the Roman province of Cilicia, whose formation process was quite long and characterized by a complicated sequence of historical and political events. The main question is formulated drawing on – though in a different geographic context – the words of G. Alföldy1: can we consider Cilicia a „typical” province of the Roman empire and how can we determine the peculiarities of this province? Moreover, always recalling a point emphasized by G. Alföldy, we have to take into account that, in order to understand the characteristics of a province, it is fundamental to appreciate its level of Romanization and its importance within the empire from the economic, political, military and cultural points of view2. -

Counterfeiting Roman Coins in the Roman Empire 1St–3Rd A.D

COUNTERFEITING ROMAN COINS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE 1ST–3RD A.D. STUDY ON THE ROMAN PROVINCES OF DACIA AND PANNONIA Abstract: This paper is based on the study of Roman silver coins, from archaeological sites located in Roman Dacia and Pannonia. Initially centered on the record of hybrid silver coins, the paper expanded its analysis on Răzvan Bogdan Gaspar counterfeit pieces as well in order to fully understand all problems of Roman silver coinage from the 1st to the 3rd centuries AD. University Babeș-Bolyai of Cluj-Napoca [email protected] The new and larger area of research had more than one implications, coin distribution on the studied sites, influx of coin in the province, quantity of recorded counterfeited pieces being just some of them. Thus every situation was discussed in different chapters, first presenting the coins and the laws that protected them, the studied sites and the analyse of the silver coins on these sites, the general and compared situation between the provinces, interpretation of the counterfeited and hybrid pieces and finally, conclusions on the subject. All these tasks have been achieved one step at a time, each archaeological site providing precious data which piled up and was finally pressed in order to present the correct historical situation. Keywords: Roman Empire, Dacia, Pannonia, archaeological sites, silver, coins, counterfeiting, hybrid, graphs, coefficient; INTRODUCTION: he area which enters this study was geographically delimited to the Roman provinces of Pannonia Inferior, Pannonia Superior, Dacia TPorolissensis and Dacia Apulensis. This bordering was chosen because it offers the possibility to compare different archaeological sites from Dacia and Pannonia between them, at the end trying to compare the results from Pannonia with those coming from Dacia in order to observe the distribution of counterfeited pieces. -

“With Friends Like This, Who Needs Enemies?”

“With friends like this, who needs enemies?” POMPEIUS ’ ABANDONMENT OF HIS FRIENDS AND SUPPORTERS There are well-known examples of Pompeius’ abandonment of his supporters: Marcus Tullius Cicero and Titus Annius Milo spring readily to mind. One could even include Pompeius’ one- time father-in-law Gaius Iulius Caesar among the number, I suppose. Theirs was a fairly spectacular falling out, leading to the final collapse of the ailing and civil-war-torn Roman republic. The bond between them, forged by the marriage of Caesar’s daughter Julia in 59 and maintained by a delicate and precarious support of each other in the first half of the 50s, was not broken by Julia’s death in childbirth in 54. Having no sons of his own, Caesar had named his son-in-law as principal heir in his will, and his name was not removed until five years later * on the outbreak of the civil war ( Passage 1 : Suet. Iul. 83.1-2), by which time Pompeius had manoeuvred himself – or had he perhaps been manoeuvred? – over to the side of the senatorial conservatives in his endless pursuit of their recognition and acceptance of him as the leading man in the state. The leitmotif of Pompeius’ manoeuvres throughout his career was an overriding concern for the personal political advantage of every move he made – what would best get him ahead in this pursuit of recognition. One of the things which shows this to good effect is his series of marriages – five of them in all. So I will begin my examination of Pompeius’ abandonment of connections, not with an obvious political supporter, but with his dealings with his first two wives, which had sad consequences for both of the ladies involved, as it turned out. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

The Cultural Creation of Fulvia Flacca Bambula

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 The cultural creation of Fulvia Flacca Bambula. Erin Leigh Wotring University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Gender Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Wotring, Erin Leigh, "The cultural creation of Fulvia Flacca Bambula." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2691. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2691 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CULTURAL CREATION OF FULVIA FLACCA BAMBULA By Erin Leigh Wotring A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in History Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, KY May, 2017 Copyright 2017 by Erin Leigh Wotring All rights reserved THE CULTURAL CREATION OF FULVIA FLACCA BAMBULA By Erin Leigh Wotring A Thesis Approved on April 14, 2017 by the following Thesis Committee: Dr. Jennifer Westerfeld, Director Dr. Blake Beattie Dr. Carmen Hardin ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. -

Henrietta Van Der Blom, Christa Gray, and Catherine Steel (Eds.)

Henrietta Van der Blom, Christa Gray, and Catherine Steel (eds.). Institutions and Ideology in Republican Rome. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2017. Hb. $120.00 USD. Institutions and Ideology in Republican Rome is a collection of papers first presented at a conference in 2014, which in turn arose from the Fragments of the Republican Roman Orators (FRRO) project. Perhaps ironically, few of these papers focus on oratorical fragments, although the ways in which Republican politicians communicated with each other and the voting public is a common theme across the collection. In their introduction the editors foreground the interplay between political institutions and ideology as a key point of conflict in late Republican politics, taking aim in particular at the interpretation of Republican political life as dominated by money and self-serving politicians at the top and by institutionally curated consensus at the bottom. This, they argue, is unsustainable, not least in light of the evidence presented by their contributors of politicians sharing and acting on ‘ideological’ motives within the constraints of Republican institutions. Sixteen papers grouped into four sections follow; the quality is consistently high, and several chapters are outstanding. The four chapters of Part I address ‘Modes of Political Communication’. Alexander Yakobson opens with an exploration of the contio as an institution where the elite were regularly hauled in front of the populus and treated less than respectfully by junior politicians they would probably have considered beneath them. He argues that the paternalism of Roman public life was undercut by the fact that ‘the “parents” were constantly fighting in front of the children’ (32). -

Dan Isac, Overlapped Forts in Roman Dacia. the Archaeological Perspective on the Architectonic Effects

Bibliografia sitului SAMVM I. ARHEOLOGIA SITULUI / TRUPELE STAŢIONATE ÎN CASTRU - Dan Isac, Overlapped Forts in Roman Dacia. The Archaeological Perspective on the Architectonic Effects. Antiquitas Istro – Pontica. Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire ancienne offerts à Alexandru Suceveanu. Editura Mega, Cluj-Napoca 2010, 241-266. - Dan Isac, Repairing Works and Reconstructions on the Limes Dacicus in the late 3rd Century AD. Limes XX. XXth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies. Anejos de Gladius 13, vol. I. Madrid 2009, 779-792. - Dan Isac, Reparaţii şi reconstrucţii în castrele Daciei romane în a doua jumătate a secolului III p.Chr. (O nouă analiză a fenomenului). Ephemeris Napocensis XVI-XVII, 2006-2007, 131-163. - Dan Isac, Castrul roman de la SAMVM-Căşeiu. The Roman Auxiliary Fort SAMVM- Căşeiu. Editura Napoca Star, Cluj-Napoca, 2003. - Dan Isac, Felix Marcu, Die Truppen im Kastell von Căşeiu: COHORS II BR(ITANNORUM) (milliaria) und COHORS I BRITANNICA (milliaria) C.R. EQVITATA ANTONINIANA. Roman Frontier Studies. Proceedings of the XVIIth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies. Zalău 1999, 585-597. - Dan Isac, Die Entwicklung der Erforschung des Limes nach 1983 im nördlichen Dakien (Porolissensis). Roman Frontier Studies. Proceedings of the XVIIth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies. Zalău 1999, 151-170. - Adriana Isac, Florin Gogâltan, Die spätbronzezeitliche Siedlung von Căşeiu (I). Ephemeris Napocensis V, 1995, 5-26. - Dan Isac, Peter Hügel, Dan Andreica, Praetoria in dakischen Militaranlagen. Saalburg- Jahrbuch 47, 1994, 40-64. - Dan Isac, Vicus Samum- eine statio der Beneficiarier an der nordlichen Grenze Dakiens. Der römische Weihebezirk von Osterburken II. Forschungen und Berichte zu Vor-und Frühgeschichte in Baden-Wurttemberg. -

Archaeology and Urban Settlement in Late Roman and Byzantine Anatolia Edited by John Haldon , Hugh Elton , James Newhard Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47115-2 — Archaeology and Urban Settlement in Late Roman and Byzantine Anatolia Edited by John Haldon , Hugh Elton , James Newhard Index More Information 369 Index Avkat, Beyözü, and Euchaïta have not been indexed f = i gure, t = table A b a n t , 3 7 , 3 8 , 4 0 Amorium, 269 Abbasids, 156 anagnōstēs (reader), 286 , 290 , 291 , 296 , 311 Acıçay River, 30 Anastasiopolis, 149 Adata, 235 Anastasius (emperor), 17 , 22 , 23 , 63 , 185 , 188 , A d a t e p e , 3 8 189 , 192 , 196 , 202 , 207 , 208 , 209 , 214 , 221 , Aegean Sea, 27 , 28 222 , 222n55 , 222n55 , 224 , 271 , 291 , 293 Aght’amar, 213 , 214n15 Anatolides- Taurides (tectonic unit), 25 , 26 Agricola from Gazacene, 20 Anatolikon (theme), 101 agricultural produce/ output, 30 , 32 , 34 , 36 , 38 , Anazarba, 235 40 , 49 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 100 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , Anazarbos. See Anazarba 107t5.1 , 109 , 110 , 113 , 114 , 123 , 125 , 127 , Anderson, J.G.C., 73 , 81 , 89 , 90 , 102 , 105 , 106 , 128 , 128n79 , 129 , 131 , 132 , 147 , 148 , 149 , 185 , 186 , 187 , 193 , 195 , 203 , 204 , 205 , 206 , 150 , 151n93 , 152 , 152n96 , 153 , 155n119 , 208 159 , 161n143 , 162 , 175 , 211 , 226 , 227 , Andrapa. See N e a p o l i s 249 , 276 Androna, 156 A h l a t . See Chliat animal husbandry/ herding, 9 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 , Ahmetsaray, 193 41 , 88 , 98 , 100 , 104 , 110 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 118 , Aizanoi, 301 123 , 132 , 148 , 149 , 150 , 155 , 159 , 165 Akören, 83n73 , 193 Ankara/Ankyra, 9 , 10 , 12 , 14 , 23 , 26 , 44 , 82 , Akroinon, 245 89 , 149 , 186 , -

The Late Republic in 5 Timelines (Teacher Guide and Notes)

1 180 BC: lex Villia Annalis – a law regulating the minimum ages at which a individual could how political office at each stage of the cursus honorum (career path). This was a step to regularising a political career and enforcing limits. 146 BC: The fall of Carthage in North Africa and Corinth in Greece effectively brought an end to Rome’s large overseas campaigns for control of the Mediterranean. This is the point that the historian Sallust sees as the beginning of the decline of the Republic, as Rome had no rivals to compete with and so turn inwards, corrupted by greed. 139 BC: lex Gabinia tabelleria– the first of several laws introduced by tribunes to ensure secret ballots for for voting within the assembliess (this one applied to elections of magistrates). 133 BC – the tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus, who along with his younger brother, is seen as either a social reformer or a demagogue. He introduced an agrarian land that aimed to distribute Roman public land to the poorer elements within Roman society (although this act quite likely increased tensions between the Italian allies and Rome, because it was land on which the Italians lived that was be redistributed). He was killed in 132 BC by a band of senators led by the pontifex maximus (chief priest), because they saw have as a political threat, who was allegedly aiming at kingship. 2 123-121 BC – the younger brother of Tiberius Gracchus, Gaius Gracchus was tribune in 123 and 122 BC, passing a number of laws, which apparent to have aimed to address a number of socio-economic issues and inequalities. -

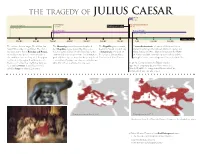

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

THE TR AGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR Transition 49–27 BC Coriolanus Caesar assassinated Roman Kingdom 494 BC Shakespeare’s play 44 BC 753–509 BC Roman Republic Roman Empire 509–49 BC 27 BC – 293 AD Roman Epochs 700 BC 600 BC 500 BC 400 BC 300 BC 200 BC 100 BC 1 AD 100 AD 200 AD The enforced vestal virgin, Rhea Silvia, has The Monarchy is overthrown and replaced The Republic grows corrupt, A second triumvirate is formed of Octavius Caesar twins fathered by the god Mars. The stolen by a Republic, a government by the people, begins to flounder and decay. (Julius Caesar’s great-nephew), Marcus Lepidus, and and abandoned twins, Romulus and Remus, headed by two consuls elected annually by the A triumvirate is formed of Mark Antony. In 27 BC, Mark Antony loses the Battle are fed by a woodpecker and nursed by a citizens and advised by a senate. A constitution Pompey the Great, Marcus of Actium and kills himself, Lepidus is exiled, and the she-wolf in a cave, the Lupercal. They grow gradually develops, centered on the principles of Crassus, and Julius Caesar. young Caesar becomes Augustus Caesar, Exalted One. up, found a city, argue, then Romulus kills a separation of powers and checks and balances. Remus and names the city Rome. OR it was All public offices are limited to one year. In 49 BC, Caesar crosses the Rubicon and is founded by Aeneas about this time. It is appointed temporary dictator three times; on ruled by kings for almost 250 years.