March 2021 Military History Group U3A Dorking Newsletter Number 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dichotomy Between British and American Women Auxiliary Pilots of World War II

Straighten Up and Fly Right: The Dichotomy between British and American Women Auxiliary Pilots of World War II Brighid Klick A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN March 31, 2014 Advised by Professor Kali Israel TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... ii Military Services and Auxiliaries ................................................................................. iii Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: Introduction of Women Pilots to the War Effort…….... ..................... 7 Chapter Two: Key Differences ..................................................................................... 37 Chapter Three: Need and Experimentation ................................................................ 65 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 91 Bibliography ................................................................................................................... 98 ii Acknowledgements I would first like to express my gratitude to my adviser Professor Israel for her support from the very beginning of this project. It was her willingness to write a letter of recommendation for a student she had just met that allowed -

13676 Genaviation Text

ATA rrr:1 Articles 18/3/08 14:53 Page 34 operational tasks, the ATA ran their own maintenance, medical, administration and AA salsalututee toto thethe AATTAA,, catering organisation. Initially the pilots who ferried the planes returned to base by train. A flying taxi service using Ansons and Fairchilds was established so that by 1943 one ATA pilot 6060 yearyearss onon did the work of three. ATA pools reached from Hamble on the Solent to Lossiemouth in the Moray Firth. When women pilots wanted to join the ATA, the sparks really flew. Pauline Gower, an MP’s daughter with 2,000 hours under her belt ferrying 30,000 passengers, wasn’t taking ‘no’ for an answer. She secured Churchill’s intervention and paved the way for more than 110 women to fly alongside 600 Great War fighter aces and commercial pilots rejected by the RAF on grounds of health or age – the self- styled Ancient and Tattered Aviators. The legendary Amy Johnson, who had flown solo to Australia, was ferrying an Oxford south via Blackpool without proper instruments. Flying above the clouds, she waited for a gap to appear; none did. Eventually she ran out of fuel and baled out over the Thames Estuary. By sheer bad luck she drowned next to a navy vessel; Lt-Commander Walter Fletcher perished attempting to save her. E.C. Cheesman, who wrote the story of the ATA in 1945, escaped the same fate when he baled out successfully after failing to get back down through the clouds. Even Douglas Bader was impressed by the women fliers and visited the home of Diana Barnato-Walker, the ATA member who later became the first British woman to break the sound barrier, and who today lives in Kent. -

Script Are Expressly Forbidden Without the Prior Written Consent of the Author Or His/Her Agent

Copyright Notice This work is fully protected under the copyright laws of Canada and all countries of the International Copyright Convention, and is subject to royalty payment. This work may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form without specific permission, in writing, from the author or his/her agent. Changes to the script are expressly forbidden without the prior written consent of the author or his/her agent. All rights to this play are strictly reserved. All rights, including publication, professional or amateur stage rights, motion picture, lecturing, recitation, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video picture or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical or electronic reproduction, such as CD-ROM, CD-I, DVD, information storage and retrieval systems and the rights of translation into foreign languages, are retained by the author. This work is available through Spitfire Productions. For information about stage performance rights or to order scripts, please contact: 416 884 4762 A Remembrance Play Spitfire Dance A Dramatic Music Entertainment in Two Acts By Clint Ward Music Director Brian Jackson Original Cast Karen Cromar Glen Bowser Brian Jackson 1st performance October 23, 2014 Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, Ontario spitfireproductions.ca 2 Characters Brian – Piano Player: Judy – Entertainer, Pauline Gower, voices: Kevin – Entertainer, Gerard d’Erlanger, one voice. Scene: Any performance space. There are two easels holding large recruiting posters of the 2nd World War. (The backs of these posters are pictures of Spitfires and the posters are turned to reveal the Spitfires at intermission). These are located in the back corners of the stage. There is also a large hanging sign at centre back, which reads, in large letters, Lest We Forget. -

The Griff January 2010.Qxp

The Griff The Magazine of the Royal Air Force Police Association R “Lest we forget” JANUARY 2010 This Issue! Regular Features Special Articles Letters to the Editor p.6 One of our aircraft went missing! p.4 Welcome to New Members p.19 St. Clement Danes Celebrations p.10 Last Post p.22 NI Army Dog Memorial p.12 Bygone Days & Years p.24 Silk Stocking & Spitfires p.20 Walk Down Memory Lane p.26 A Perfect Partnership: final part p.21 Views expressed in The Griff are those of the Editor and individual contributors and do not necessarily represent RAFPA policy. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any person, at any time, by any method, without the express permission of the Editor or originator in writing. Page 2 2010 The Griff Page 3 2010 Who’s Who in the RAF Police Association - 2010 Hon. President Hon. Vice PresidPresidentent Air Cdre. Steven Abbott C.B.E Gp. Capt. JohnG. D. W.Horscroft Whitmell, M.Phil., BA, RAF, ACoS FP, AO RAF Police MA,MA Ed,MSc, BA, BSc, PM Provost(RAF). Marshal (RAF ) Life Vice Presidents: Steve Cattell, E Mail [email protected] Neil Rusling, E Mail [email protected] David Wardell, E Mail [email protected] Elected Officers Chairman: Brian G. Flinn Vice Chairman: Alan Millership (J.P) 11, Beverley Way 38 Pennine Road, Thorne, Doncaster, Cepen Park South, Chippenham South Yorkshire DN8 5RU Wilts., SN14 0XS Tel. No. 01405 818159 Tel. No. 01249 460318 Mob: 07849 468366 E.Mail: [email protected] E.Mail: [email protected] Treasurer: Tony Lake Secretary: David Wardell 24 Trendlewood Park, Stapleton, 40, South Western Crescent Bristol BS16 1TE Poole, Dorset, BH14 8RR Tel: 0117 965 2302 Tel/Fax 01202 747176 E Mail: [email protected] E Mail: [email protected] Voluntary Posts RAFPA Archivist: John Curtis Editor The Griff: Mitch O'Neill 28 Tennyson Avenue, Gedling, 11, Florentine Way, Waterlooville, Nottingham, NG4 3HJ Hampshire, PO7 8JY Tel.No. -

Forever Sampler

Connect with us! @ReadForeverPub #ReadForever Read-Forever.com FindYourForeverTrope.com Hello Librarians! Welcome and thank you for joining Forever at ALA Annual! Your tireless dedication and commitment to getting books into the hands of readers is always a thing of wonder, but no more so than now, when getting books to readers is one of our greatest challenges. We are so appreciative of the hard work that’s gone into keeping all of us both safe and surrounded by the books we love! I’m thrilled to introduce you to Forever’s Digital Sampler of our upcoming titles, which includes books that will make you laugh, make you cry—and will always deliver an HEA to make you smile. In the much-anticipated The Paris Secret, New York Times bestselling author Natasha Lester will transport you to WWII-Paris, with an unforgettable story of love, sacrifice, and the hardships faced by the first female pilots. Across the English Channel, award-winning author Manda Collins speaks truth to power in A Lady’s Guide to Mischief & Mayhem, a fresh and flirty Victorian London-set rom-com about an intrepid lady reporter and the tall, dark, and serious detective with whom she matches wits! Fast-forwarding to the present-day, we simply cannot stop texting, tweeting, and chatting over Farrah Rochon’s heartwarming and hysterical trade paperback debut The Boyfriend Project! Fans of Abby Jimenez and Jasmine Guillory will love Farrah’s friendship-driven romantic comedy about three women who go viral when they discover they’ve all been catfished by the same boyfriend! In Katherine Slee’s charming debut, The Book of Second Chances, the shy granddaughter of a beloved children’s author makes her own life-changing pact— to follow the clues her grandmother left behind and embark on a journey that takes her to bookstores around the globe. -

The Royal British Legion Learning Pack 2011/2012

The Royal British Legion is the nation’s leading Armed Forces charity, providing care and support to all members of the British Armed Forces past and present, and their families. For 90 years it has also been the national custodian of Remembrance, safeguarding the Military Covenant between the nation and its Armed Forces. It is best known for the annual Poppy Appeal and its emblem, the red poppy. The Legion is committed to helping ABOUT THIS young people understand the issues of Remembrance, conflict and the importance of peace, using informed, integrated and constructive methods. LEARNING RESOURCE The Royal British Legion’s The topics support the explore. The disks cover This pack is designed Remembrance Women in war free learning resources current areas of the National the themes and issues of to assist teachers How it all began and why How the role of women are updated annually and Curriculum for the following Remembrance; international and other learning it is still so important today. has changed over the last developed to reflect the units: conflicts and peacetime facilitators to introduce The Two Minute Silence and 120 years, in conflict and changing needs of schools operations from World specific themes into the relevance of memorials. on the home front. Women and other informal learning History War I to the present day; the classroom. in the Armed Forces today. groups. This year, some Key Stages 1 and 2 international organisations Primarily it covers the of the sections have been • Commemorative days and the world leaders and History and Citizenship strengthened to support, • World War I ordinary people who have curricula, but it can 2 16 in particular, the teaching Key Stage 3 influenced and witnessed also be used to support of Remembrance. -

Ates Women in Aviation 1940-1985 Deborah G

Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Number 7 nite ates women in Aviation 1940-1985 Deborah G. Douglas SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and simitar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

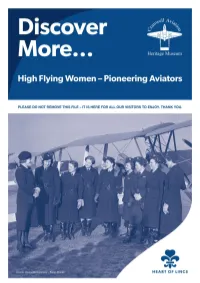

Introduction

Introduction This file contains material and images which are intended to complement the displays and presentations in Cranwell CranwellAviation Heritage Aviation Museum Heritage’s exhibition Centre areas. HighThis file Flying is intended Women to let you –discover Pioneering more about Aviators the female aviators who achieved their dreams and set aviation history. The information contained in this file has been obtained from a number of sources which are detailed at the rear of this file. This file is the property of Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum, a North Kesteven District Council service. The contents are not to be reproduced or further disseminated in any format, without written permission from North Kesteven District Council. 0 This is the property of Cranwell Aviation Heritage Centre, a North Kesteven District Council service. The contents are not to be reproduced or further disseminated in any format without written permission from NKDC. Introduction This file contains material and images which are intended to complement the displays and presentations in Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum’s exhibition areas. This file is intended to let you discover more about the female aviators who achieved their dreams and set aviation history. The information contained in this file has been obtained from a number of sources. This file is the property of Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum, a North Kesteven District Council service. The contents are not to be reproduced or further disseminated in any format, without written permission from North Kesteven District Council. 1 This is the property of Cranwell Aviation Heritage Centre, a North Kesteven District Council service. The contents are not to be reproduced or further disseminated in any format without written permission from NKDC. -

A Bibliography of Works About and by Females and Minorities in Aviation

A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF WORKS ABOUT AND BY FEMALES AND MINORITIES IN AVIATION. PREPARED BY PROFESSOR JOSEPH D. SUAREZ UNIVERSITY OF DUBUQUE JANUARY 2006 A Bibliography of works for and by females and minorities in aviation. Produced with the help of grant No. WO41022A COA from the Wolf Aviation Fund. Prepared by Professor Joseph D. Suarez, University of Dubuque, Dubuque, Iowa. January, 2006. Professor Suarez would like to thank the following persons for their time and assistance: Θ Mr. Doug Scott, Jr., Interim Director of Multicultural Services at the University of Dubuque, for his research assistance Θ Mrs. Kim Bruggenwirth, Aviation Office Manager, for her assistance with the University of Dubuque website. Θ Mrs. Mary Anne Knefel, Library Director for her help with Endnote. The purpose of this bibliography is to provide a source of information for researchers and others interested in the contribution to aviation made by females and minorities since the conception of heavier than air flight by the Wright brothers in 1903 and even earlier. Therefore as much information as possible is included with each citation. The bibliography will be updated on an ongoing basis. We invite use of the bibliography with appropriate attribution to the University of Dubuque and Professor Suarez. The work is divided into several sections and as much detail as possible have been kept to assist the researcher. The material is organized by document type and alphabetically by author. The major sections are: Citation Type Page Audiovisual materials 4 Books 71 Electronic Books & Online Databases 166 Generic & Miscellaneous 175 Government Documents 181 Journal Articles 196 Magazine Articles 204 Personal Communications 207 Thesis 217 Audiovisual material –Alphabetically by Author Sixty eight pages and 133 citations The audiovisual citations include videocassettes, movies, audio recordings of various types and photographs. -

Air Transport Auxiliary at Hamble

Air Transport Auxiliary at Hamble At the beginning of the Second World War the ATA was set up to enable RAF pilots to undertake operational duties rather than move aircraft around the country between factories, maintenance units and airfields. Volunteers, who would not have normally met the RAF requirements for operational service because of their age, medial/physical limitations, were trained to undertake these duties. Initially the ATA only took male applicants but soon accepted females as well, and it was the first major organisation to treat men and women equally as a matter of policy e.g. pay, duties, uniform etc. The well known female pilot Amy Johnson joined the ATA and was killed in service on a delivery flight. ATA pilots were restricted to flying in daylight and without a radio. They were confined to ‘contact’ navigation which meant always being in the sight of the ground and they found their way by using a map. As there were over 100 types of aircraft to deliver they were classed in difficulty and flown by ATA pilots with the appropriate training and experience. Class 1 consisted of light aircraft which were the first flown by the new pilots. Next was Class 2 single engine fighters such as the Spitfire & Hurricane, while Class 5 contained four engine aircraft such as Lancaster & Halifax bombers. The highest Class 6, Flying Boats, was the only one that women did not eventually fly. As it was essential to have information available to fly unfamiliar aircraft at short notice the ATA produced Ferry Pilot Notes, a booklet which contained concise vital information on each of the aircraft, to enable pilots to deliver them even if they had not flown that type before. -

The Ata Girls French Wing 2009/2010 Annual

http://www.caffrenchwing.fr Volume 14 - N° 5 - May 2009 THE ATA GIRLS EDITORIAL “Always Terrified Airwomen” ur mechanics have worked very hard AN HOMAGE TO THE WOMEN, UNSUNG HEROES, OF so that the annual checks on the Piper O (Pages 7 to 11). Cub and the NC 856 could be completed THE AIR TRANSPORT AUXILIARY in time for the renewal of their respective airworthiness certificate. As you will see in the following pages, they took this opportu- nity to improve the look of these planes by the addition of the CAF logo, and by giving back the NC 856 the livery it had while it was stationed in Algeria. The plane will be dis- played in the static area of the La Ferté-Alais air show, where it will proudly represent our organization. We hope to see you all there on May 30 and 31 ! ith Spring, comes the need to renew Wyour membership with the French Wing. I ask all our members who haven’t yet paid their annual dues, to send 50€ to the French WIng (20€ for the Cadets), and, as far as our friends in the USA are concerned, to send a $ 50.00 check to Roy and Irene Grinnell. Please check the list of members who are up to date, and if you cannot see your name, please send NEW LOOK FOR THE NC 856 your dues at once. Thanks ! THE PLANE e only need 200 euros to reach the WAS ROLLED Wrequired amount of money so that the Spirit of Lewis can operate without any OUT OF THE problem !A big thank you to everyone who HANGAR reacted to my last month call ! Just a little WITH ITS effort from those members who did not renew their support to this plane, and we will enjoy BRAND NEW : B. -

Air Pilot Master

AirPilot DECEMBER 2014 ISSUE 6 Diary DECEMBER 2014 9 Technical and Air Safety Committee Meeting Cobham House 12 Company Carol Service St Michael's Cornhill AI R PILOT 12 Christmas Supper The Counting House THE HONOURABLE 19 Office closes until 5 Jan JANUARY 2015 COMPANY OF 5 Office opens AIR PILOTS 13 Education and Training Committee Meeting Cobham House incorporating 14 Trophies and Awards Committee Meeting Cobham House Air Navigators 20 Benevolent Fund Board of Trustees AGM RAF Club 20 Environment Committee Meeting Cobham House PATRON : 22 9th General Purposes and Finance Committee Meeting Cobham House His Royal Highness 22 5th Court Meeting Cutlers' Hall The Prince Philip 22 Court Election Dinner Cutlers' Hall Duke of Edinburgh KG KT FEBRUARY 2015 3 Technical and Air Safety Committee Meeting Cobham House GRAND MASTER : 26 10th General Purposes and Finance Committee Meeting Cobham House His Royal Highness 26 6th Court Meeting Cutlers' Hall The Prince Andrew Duke of York KG GCVO MARCH 2015 3 Education and Training Committee Meeting Cobham House 9 Annual Service St Michael's Cornhill MASTER : Dorothy Saul-Pooley 9 AGM, Installation and Supper Merchant Taylors' Hall LLB (Hons) FRAeS 19 Lord Mayor's Dinner for Masters Mansion House 20 United Guilds' Service St Paul's Cathedral CLERK : 20 Lunch with Fan Makers' Company Skinners' Hall Paul J Tacon BA FCIS APRIL 2015 9 Benevolent Fund Board of Trustees Meeting Cobham House Incorporated by Royal Charter. 16 1st General Purpose and Finance Committee Meeting Cobham House A Livery Company of the City of London. 23 Assistants’ Dinner Cutler’s Hall 23 New Members’ Briefing Cobham House PUBLISHED BY : The Honourable Company of Air Pilots, 30 Luncheon Club RAF Club Cobham House, 9 Warwick Court, 30 Cobham Lecture Royal Aeronautical Society Gray’s Inn, London WC1R 5DJ.