Loss of Keratin 13 in Oral Carcinoma in Situ: a Comparative Study of Protein and Gene Expression Levels Using Paraffin Sections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular Pathways Associated with the Nutritional Programming of Plant-Based Diet Acceptance in Rainbow Trout Following an Early Feeding Exposure Mukundh N

Molecular pathways associated with the nutritional programming of plant-based diet acceptance in rainbow trout following an early feeding exposure Mukundh N. Balasubramanian, Stéphane Panserat, Mathilde Dupont-Nivet, Edwige Quillet, Jérôme Montfort, Aurélie Le Cam, Françoise Médale, Sadasivam J. Kaushik, Inge Geurden To cite this version: Mukundh N. Balasubramanian, Stéphane Panserat, Mathilde Dupont-Nivet, Edwige Quillet, Jérôme Montfort, et al.. Molecular pathways associated with the nutritional programming of plant-based diet acceptance in rainbow trout following an early feeding exposure. BMC Genomics, BioMed Central, 2016, 17 (1), pp.1-20. 10.1186/s12864-016-2804-1. hal-01346912 HAL Id: hal-01346912 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01346912 Submitted on 19 Jul 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Balasubramanian et al. BMC Genomics (2016) 17:449 DOI 10.1186/s12864-016-2804-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Molecular pathways associated with the nutritional programming of plant-based diet acceptance in rainbow trout following an early feeding exposure Mukundh N. Balasubramanian1, Stephane Panserat1, Mathilde Dupont-Nivet2, Edwige Quillet2, Jerome Montfort3, Aurelie Le Cam3, Francoise Medale1, Sadasivam J. Kaushik1 and Inge Geurden1* Abstract Background: The achievement of sustainable feeding practices in aquaculture by reducing the reliance on wild-captured fish, via replacement of fish-based feed with plant-based feed, is impeded by the poor growth response seen in fish fed high levels of plant ingredients. -

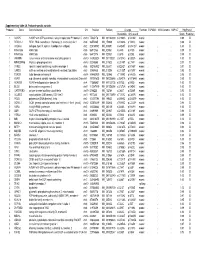

Supplementary Table 2A. Proband-Specific Variants Proband

Supplementary table 2A. Proband-specific variants Proband Gene Gene full name Chr Position RefSeqChange Function ESP6500 1000 Genome SNP137 PolyPhen2 Nucleotide Amino acid Score Prediction 1 AGAP5 ArfGAP with GTPase domain, ankyrin repeat and PH domain 5 chr10 75435178 NM_001144000 c.G1240A p.V414M exonic . 0.99 D 1 REXO1L1 REX1, RNA exonuclease 1 homolog (S. cerevisiae)-like 1 chr8 86574465 NM_172239 c.A1262G p.Y421C exonic . 0.98 D 1 COL4A3 collagen, type IV, alpha 3 (Goodpasture antigen) chr2 228169782 NM_000091 c.G4235T p.G1412V exonic . 1.00 D 1 KIAA1586 KIAA1586 chr6 56912133 NM_020931 c.C44G p.A15G exonic . 0.99 D 1 KIAA1586 KIAA1586 chr6 56912176 NM_020931 c.C87G p.D29E exonic . 0.99 D 1 JAKMIP3 Janus kinase and microtubule interacting protein 3 chr10 133955524 NM_001105521 c.G1574C p.G525A exonic . 1.00 D 1 MPHOSPH8 M-phase phosphoprotein 8 chr13 20240685 NM_017520 c.C2140T p.L714F exonic . 0.97 D 1 SYNE1 spectrin repeat containing, nuclear envelope 1 chr6 152783902 NM_033071 c.A2242T p.N748Y exonic . 0.97 D 1 CAND2 cullin-associated and neddylation-dissociated 2 (putative) chr3 12858835 NM_012298 c.C2125T p.H709Y exonic . 0.95 D 1 TDRD9 tudor domain containing 9 chr14 104460909 NM_153046 c.T1289G p.V430G exonic . 0.96 D 2 ASPM asp (abnormal spindle) homolog, microcephaly associated (Drosophila)chr1 197091625 NM_001206846 c.G3491A p.R1164H exonic . 0.99 D 2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 chr4 175896951 NM_001130705 c.A275G p.D92G exonic . 1.00 D 2 BCO2 beta-carotene oxygenase 2 chr11 112087019 NM_001256398 c.G1373A p.G458E exonic . -

CDH12 Cadherin 12, Type 2 N-Cadherin 2 RPL5 Ribosomal

5 6 6 5 . 4 2 1 1 1 2 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R B , B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B B , 9 , , , , 4 , , 3 0 , , , , , , , , 6 2 , , 5 , 0 8 6 4 , 7 5 7 0 2 8 9 1 3 3 3 1 1 7 5 0 4 1 4 0 7 1 0 2 0 6 7 8 0 2 5 7 8 0 3 8 5 4 9 0 1 0 8 8 3 5 6 7 4 7 9 5 2 1 1 8 2 2 1 7 9 6 2 1 7 1 1 0 4 5 3 5 8 9 1 0 0 4 2 5 0 8 1 4 1 6 9 0 0 6 3 6 9 1 0 9 0 3 8 1 3 5 6 3 6 0 4 2 6 1 0 1 2 1 9 9 7 9 5 7 1 5 8 9 8 8 2 1 9 9 1 1 1 9 6 9 8 9 7 8 4 5 8 8 6 4 8 1 1 2 8 6 2 7 9 8 3 5 4 3 2 1 7 9 5 3 1 3 2 1 2 9 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 5 9 5 3 2 6 3 4 1 3 1 1 4 1 4 1 7 1 3 4 3 2 7 6 4 2 7 2 1 2 1 5 1 6 3 5 6 1 3 6 4 7 1 6 5 1 1 4 1 6 1 7 6 4 7 e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p p m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m m -

140503 IPF Signatures Supplement Withfigs Thorax

Supplementary material for Heterogeneous gene expression signatures correspond to distinct lung pathologies and biomarkers of disease severity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis Daryle J. DePianto1*, Sanjay Chandriani1⌘*, Alexander R. Abbas1, Guiquan Jia1, Elsa N. N’Diaye1, Patrick Caplazi1, Steven E. Kauder1, Sabyasachi Biswas1, Satyajit K. Karnik1#, Connie Ha1, Zora Modrusan1, Michael A. Matthay2, Jasleen Kukreja3, Harold R. Collard2, Jackson G. Egen1, Paul J. Wolters2§, and Joseph R. Arron1§ 1Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, CA 2Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA 3Department of Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, CA ⌘Current address: Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, Emeryville, CA. #Current address: Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA. *DJD and SC contributed equally to this manuscript §PJW and JRA co-directed this project Address correspondence to Paul J. Wolters, MD University of California, San Francisco Department of Medicine Box 0111 San Francisco, CA 94143-0111 [email protected] or Joseph R. Arron, MD, PhD Genentech, Inc. MS 231C 1 DNA Way South San Francisco, CA 94080 [email protected] 1 METHODS Human lung tissue samples Tissues were obtained at UCSF from clinical samples from IPF patients at the time of biopsy or lung transplantation. All patients were seen at UCSF and the diagnosis of IPF was established through multidisciplinary review of clinical, radiological, and pathological data according to criteria established by the consensus classification of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS), Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS), and the Latin American Thoracic Association (ALAT) (ref. 5 in main text). Non-diseased normal lung tissues were procured from lungs not used by the Northern California Transplant Donor Network. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Cloud-Clone 16-17

Cloud-Clone - 2016-17 Catalog Description Pack Size Supplier Rupee(RS) ACB028Hu CLIA Kit for Anti-Albumin Antibody (AAA) 96T Cloud-Clone 74750 AEA044Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Growth Hormone Antibody (Anti-GHAb) 96T Cloud-Clone 74750 AEA255Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Apolipoprotein Antibodies (AAHA) 96T Cloud-Clone 74750 AEA417Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Proteolipid Protein 1, Myelin Antibody (Anti-PLP1) 96T Cloud-Clone 74750 AEA421Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody (Anti- 96T Cloud-Clone 74750 MOG) AEA465Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Sperm Antibody (AsAb) 96T Cloud-Clone 74750 AEA539Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Myelin Basic Protein Antibody (Anti-MBP) 96T Cloud-Clone 71250 AEA546Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-IgA Antibody 96T Cloud-Clone 71250 AEA601Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Myeloperoxidase Antibody (Anti-MPO) 96T Cloud-Clone 71250 AEA747Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Complement 1q Antibody (Anti-C1q) 96T Cloud-Clone 74750 AEA821Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-C Reactive Protein Antibody (Anti-CRP) 96T Cloud-Clone 74750 AEA895Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Insulin Receptor Antibody (AIRA) 96T Cloud-Clone 74750 AEB028Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Albumin Antibody (AAA) 96T Cloud-Clone 71250 AEB264Hu ELISA Kit for Insulin Autoantibody (IAA) 96T Cloud-Clone 74750 AEB480Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Mannose Binding Lectin Antibody (Anti-MBL) 96T Cloud-Clone 88575 AED245Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase Antibodies (Anti-GAD) 96T Cloud-Clone 71250 AEK505Hu ELISA Kit for Anti-Heparin/Platelet Factor 4 Antibodies (Anti-HPF4) 96T Cloud-Clone 71250 CCA005Hu CLIA Kit for Angiotensin II -

Keratin 17 Regulates Nuclear Morphology and Chromatin Organization Justin T

© 2020. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2020) 133, jcs254094. doi:10.1242/jcs.254094 SHORT REPORT Keratin 17 regulates nuclear morphology and chromatin organization Justin T. Jacob1,*, Raji R. Nair1,2, Brian G. Poll1,‡, Christopher M. Pineda2, Ryan P. Hobbs§,1, Michael J. Matunis1,3 and Pierre A. Coulombe1,2,4,5,¶ ABSTRACT et al., 2006; Jacob et al., 2018). We and others recently discovered Keratin 17 (KRT17; K17), a non-lamin intermediate filament protein, that select keratins and other non-lamin IF proteins can localize to the α was recently found to occur in the nucleus. We report here on nucleus, contain functional importin -dependent nuclear K17-dependent differences in nuclear morphology, chromatin localization signal (NLS) sequences, and participate in nuclear organization, and cell proliferation. Human tumor keratinocyte cell processes, such as transcriptional control of gene expression, cell lines lacking K17 exhibit flatter nuclei relative to normal. Re-expression cycle progression, and protection from senescence (Escobar-Hoyos of wild-type K17, but not a mutant form lacking an intact nuclear et al., 2015; Hobbs et al., 2015, 2016; Kumeta et al., 2013; Zhang localization signal (NLS), rescues nuclear morphology in KRT17-null et al., 2018; Zieman et al., 2019). cells. Analyses of primary cultures of skin keratinocytes from a mouse Before these findings, the generally accepted notion was that, strain expressing K17 with a mutated NLS corroborated these findings. with the exception of type V nuclear lamins, IF proteins strictly Proteomics screens identified K17-interacting nuclear proteins with reside in the cytoplasm (Hobbs et al., 2016). -

The Correlation of Keratin Expression with In-Vitro Epithelial Cell Line Differentiation

The correlation of keratin expression with in-vitro epithelial cell line differentiation Deeqo Aden Thesis submitted to the University of London for Degree of Master of Philosophy (MPhil) Supervisors: Professor Ian. C. Mackenzie Professor Farida Fortune Centre for Clinical and Diagnostic Oral Science Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry Queen Mary, University of London 2009 Contents Content pages ……………………………………………………………………......2 Abstract………………………………………………………………………….........6 Acknowledgements and Declaration……………………………………………...…7 List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………8 List of Tables………………………………………………………………………...12 Abbreviations….………………………………………………………………..…...14 Chapter 1: Literature review 16 1.1 Structure and function of the Oral Mucosa……………..…………….…..............17 1.2 Maintenance of the oral cavity...……………………………………….................20 1.2.1 Environmental Factors which damage the Oral Mucosa………. ….…………..21 1.3 Structure and function of the Oral Mucosa ………………...….……….………...21 1.3.1 Skin Barrier Formation………………………………………………….……...22 1.4 Comparison of Oral Mucosa and Skin…………………………………….……...24 1.5 Developmental and Experimental Models used in Oral mucosa and Skin...……..28 1.6 Keratinocytes…………………………………………………….….....................29 1.6.1 Desmosomes…………………………………………….…...............................29 1.6.2 Hemidesmosomes……………………………………….…...............................30 1.6.3 Tight Junctions………………………….……………….…...............................32 1.6.4 Gap Junctions………………………….……………….….................................32 -

Chloride Channels Regulate Differentiation and Barrier Functions

RESEARCH ARTICLE Chloride channels regulate differentiation and barrier functions of the mammalian airway Mu He1†*, Bing Wu2†, Wenlei Ye1, Daniel D Le2, Adriane W Sinclair3,4, Valeria Padovano5, Yuzhang Chen6, Ke-Xin Li1, Rene Sit2, Michelle Tan2, Michael J Caplan5, Norma Neff2, Yuh Nung Jan1,7,8, Spyros Darmanis2*, Lily Yeh Jan1,7,8* 1Department of Physiology, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, United States; 2Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, San Francisco, United States; 3Department of Urology, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, United States; 4Division of Pediatric Urology, University of California, San Francisco, Benioff Children’s Hospital, San Francisco, United States; 5Department of Cellular and Molecular Physiology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Heaven, United States; 6Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Care, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, United States; 7Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, United States; 8Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, United States *For correspondence: Abstract The conducting airway forms a protective mucosal barrier and is the primary target of [email protected] (MH); [email protected] airway disorders. The molecular events required for the formation and function of the airway (SD); mucosal barrier, as well as the mechanisms by which barrier dysfunction leads to early onset airway [email protected] (LYJ) diseases, -

Appendix 2. Significantly Differentially Regulated Genes in Term Compared with Second Trimester Amniotic Fluid Supernatant

Appendix 2. Significantly Differentially Regulated Genes in Term Compared With Second Trimester Amniotic Fluid Supernatant Fold Change in term vs second trimester Amniotic Affymetrix Duplicate Fluid Probe ID probes Symbol Entrez Gene Name 1019.9 217059_at D MUC7 mucin 7, secreted 424.5 211735_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 416.2 206835_at STATH statherin 363.4 214387_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 295.5 205982_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 288.7 1553454_at RPTN repetin solute carrier family 34 (sodium 251.3 204124_at SLC34A2 phosphate), member 2 238.9 206786_at HTN3 histatin 3 161.5 220191_at GKN1 gastrokine 1 152.7 223678_s_at D SFTPA2 surfactant protein A2 130.9 207430_s_at D MSMB microseminoprotein, beta- 99.0 214199_at SFTPD surfactant protein D major histocompatibility complex, class II, 96.5 210982_s_at D HLA-DRA DR alpha 96.5 221133_s_at D CLDN18 claudin 18 94.4 238222_at GKN2 gastrokine 2 93.7 1557961_s_at D LOC100127983 uncharacterized LOC100127983 93.1 229584_at LRRK2 leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 HOXD cluster antisense RNA 1 (non- 88.6 242042_s_at D HOXD-AS1 protein coding) 86.0 205569_at LAMP3 lysosomal-associated membrane protein 3 85.4 232698_at BPIFB2 BPI fold containing family B, member 2 84.4 205979_at SCGB2A1 secretoglobin, family 2A, member 1 84.3 230469_at RTKN2 rhotekin 2 82.2 204130_at HSD11B2 hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 2 81.9 222242_s_at KLK5 kallikrein-related peptidase 5 77.0 237281_at AKAP14 A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 14 76.7 1553602_at MUCL1 mucin-like 1 76.3 216359_at D MUC7 mucin 7, -

Multifaceted Role of Keratins in Epithelial Cell Differentiation and Transformation

J Biosci (2019) 44:33 Ó Indian Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1007/s12038-019-9864-8 (0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) Review Multifaceted role of keratins in epithelial cell differentiation and transformation 1,2 1 1,2 1,2 CRISMITA DMELLO ,SAUMYA SSRIVASTAVA ,RICHA TIWARI ,PRATIK RCHAUDHARI , 1,2 1,2 SHARADA SAWANT and MILIND MVAIDYA * 1Vaidya Laboratory, Advanced Centre for Treatment, Research and Education in Cancer (ACTREC), Tata Memorial Centre (TMC), Kharghar, Navi Mumbai 410210, India 2Homi Bhabha National Institute, Training School Complex, Anushakti Nagar, Mumbai 400085, India *Corresponding author (Email, [email protected]) MS received 18 September 2018; accepted 19 December 2018; published online 8 April 2019 Keratins, the epithelial-predominant members of the intermediate filament superfamily, are expressed in a pairwise, tissue- specific and differentiation-dependent manner. There are 28 type I and 26 type II keratins, which share a common structure comprising a central coiled coil a-helical rod domain flanked by two nonhelical head and tail domains. These domains harbor sites for major posttranslational modifications like phosphorylation and glycosylation, which govern keratin function and dynamics. Apart from providing structural support, keratins regulate various signaling machinery involved in cell growth, motility, apoptosis etc. However, tissue-specific functions of keratins in relation to cell proliferation and differ- entiation are still emerging. Altered keratin expression pattern during and after malignant transformation is reported to modulate different signaling pathways involved in tumor progression in a context-dependent fashion. The current review focuses on the literature related to the role of keratins in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation and transfor- mation in different types of epithelia. -

Gene Expression Profiling of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.1.557 Gene Expression Profiling of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma RESEARCH ARTICLE Gene Expression Profiling of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Ittisak Subrungruang1, Charin Thawornkuno2, Porntip Chawalitchewinkoon- Petmitr3, Chawalit Pairojkul4,6, Sopit Wongkham5,6, Songsak Petmitr2* Abstract Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is ranked as one of the top five causes of cancer-related deaths. ICC in Thai patients is associated with infection with the liver fluke,Opisthorchis viverrini, but the molecular basis for development remains unclear. The present study employed a microarray approach to compare gene expression profiles of ICCs and normal liver tissues from the same patients residing in Northeast Thailand, a region with a high prevalence of liver fluke infection. In ICC samples, 2,821 and 1,361 genes were found to be significantly up- and down-regulated respectively (unpaired t-test, p<0.05; fold-change ≥2.0). For validation of the microarray results, 7 up-regulated genes (FXYD3, GPRC5A, CEACAM5, MUC13, EPCAM, TMC5, and EHF) and 3 down- regulated genes (CPS1, TAT, and ITIH1) were selected for confirmation using quantitative RT-PCR, resulting in 100% agreement. The metallothionine heavy metal pathway contains the highest percentage of genes with statistically significant changes in expression. This study provides exon-level expression profiles in ICC that should be fruitful in identifying novel genetic markers for classifying and possibly early diagnosis of this highly fatal type of cholangiocarcinoma. Keywords: Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma - gene expression profile - metallothione heavy metal pathway Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev, 14 (1), 557-563 Introduction using cDNA microarray have been generated, showing that O.