Note Towards the Definition of a Psychedelic Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Methodological Role of Marxism in Merleau-Ponty's

On the Methodological Role of Marxism in Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology Abstract While contemporary scholarship on Merleau-Ponty virtually overlooks his postwar existential Marxism, this paper argues that the conception of history contained in the latter plays a signifi- cant methodological role in supporting the notion of truth that operates within Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological analyses of embodiment and the perceived world. This is because this con- ception regards the world as an unfinished task, such that the sense and rationality attributed to its historical emergence conditions the phenomenological evidence used by Merleau-Ponty. The result is that the content of Phenomenology of Perception should be seen as implicated in the normative framework of Humanism and Terror. Keywords: Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology, Methodology, Marxism, History On the Methodological Role of Marxism in Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology In her 2007 book Merleau-Ponty and Modern Politics after Anti-Humanism, Diana Coole made the claim (among others) that Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology is “profoundly and intrinsically political,”1 and in particular that it would behoove readers of his work to return to the so-called ‘communist question’ as he posed it in the immediate postwar period.2 For reasons that basical- ly form the substance of this paper, I think that these claims are generally correct and well- taken. But this is in spite of the fact that they go very distinctly against the grain of virtually all contemporary scholarship on Merleau-Ponty. For it is the case that very few scholars today – and this is particularly true of philosophers – have any serious interest in the political dimen- sions of Merleau-Ponty’s work. -

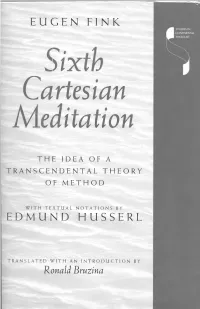

Cartesian Meditation

EUGEN FINK Sixth Cartesian Meditation THE IDEA OF A TRANSCENDENTAL THEORY OF METHOD WITH TEXTUAL NOTATIONS BY EDMUND HUSSERL TRANSLATED WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY Ronald Brutina EUGEN FINK Sixth Cartesian Meditation THE IDEA OF A TRANSCENDENTAL THEORY OF METHOD WITH NOTATIONS BY EDMUND HUSSERL TRANSLATED WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY Ronald Bruzina "... a thorough critique of Husserl's transcendental phenomenology . raises many new questions. a classic." — J. N. M ohanty Eugen Fink's Sixth Cartesian Medita tion, accompanied by Edmund Husserl's detailed and extensive notations, is a pivotal document in the development of one of the dominant philosophical directions of the twentieth century, Husserlian transcendental phe nomenology. Meant to follow a systematic revision of Husserl's first five Cartesian Meditations, (continued on back flap) Sixth Cartesian Meditation Studies in Continental Thought John Sallis, general editor Consulting Editors Robert Bernasconi W illia m L. M cBride Rudolf Bernet J. N. Mohanty John D. Caputo M ary Rawlinson David Carr Tom Rockmore Edward S. Casey Calvin O . Schrag Hubert L. Dreyfus f Reiner Schiirmann D o n Ih d e C h a rle s E. Scott David Farrell Krell Thomas Sheehan Lenore Langsdorf Robert Sokolowski Alphonso Lingis Bruce W . Wilshire D a v id W o o d Sixth Cartesian Meditation T H E ID EA OF A TRANSCENDENTAL THEORY OF M E T H O D WITH TEXTUAL NOTATIONS BY EDMUND HUSSERL TRANSLATED WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY Ronald Bruzina INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS BLOOMINGTON & INDIANAPOLIS Published in G erm an as Eugen Fink, Vi. Cartesianische Meditation.Teil 1. Die Idee Einer Transzendentalen Metbodenlebrr, edited by Hans Ebeling, Jann H o ll, and Guy van K.erckhoven. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Husserl and Ricoeur the Influence of Phenomenology on the Formation of Ricoeur’S Hermeneutics of the ‘Capable Human’

Husserl and Ricoeur The Influence of Phenomenology on the Formation of Ricoeur’s Hermeneutics of the ‘Capable Human’ Dermot Moran Journal of French and Francophone Philosophy - Revue de la philosophie française et de langue française, Vol XXV, No 1 (2017) pp 182-199. Vol XXV, No 1 (2017) ISSN 1936-6280 (print) ISSN 2155-1162 (online) DOI 10.5195/jffp.2017.800 www.jffp.org This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This journal is operated by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program, and is co-sponsored by the UniversityJournal of Pittsburgh of French and Press Francophone Philosophy | Revue de la philosophie française et de langue française Vol XXV, No 1 (2017) | www.jffp.org | DOI 10.5195/jffp.2017.800 Husserl and Ricoeur The Influence of Phenomenology on the Formation of Ricoeur’s Hermeneutics of the ‘Capable Human’ Dermot Moran University College Dublin & Wuhan University The phenomenology of Edmund Husserl had a permanent and profound impact on the philosophical formation of Paul Ricoeur. One could truly say, paraphrasing Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s brilliant 1959 essay “The Philosopher and his Shadow,”1 that Husserl is the philosopher in whose shadow Ricoeur, like Merleau-Ponty, also stands, the thinker to whom he constantly returns. Husserl is Ricoeur’s philosopher of reflection, par excellence. Indeed, Ricoeur always invokes Husserl when he is discussing a paradigmatic instance of contemporary philosophy of “reflection” and also of descriptive, “eidetic” phenomenology.2 Indeed, I shall argue in this chapter that Husserl’s influence on Ricoeur was decisive and provided a methodology which is permanently in play, even when it has to be concretized and mediated by hermeneutics, as Ricoeur proposes after 1960. -

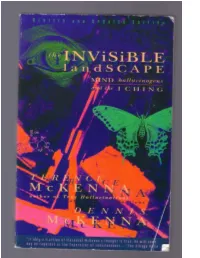

THE INVISIBLE LANDSCAPE: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching

To inquire about Time Wave software in both Macintosh and DOS versions please contact Blue Water Publishing at 1-800-366-0264. fax# (503) 538-8485. or write: P.O. Box 726 Newberg, OR 97132 Passage from The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, edited by David V. Erdman. Commentary by Harold Bloom. Copyright © 1965 by David V. Erdman and Harold Bloom. Published by Doubleday Company, Inc. Used by permission. THE INVISIBLE LANDSCAPE: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching. Copyright © 1975, 1993 by Dennis J. McKenna and Terence K. McKenna. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022. Interior design by Margery Cantor and Jaime Robles FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1975 BY THE SEABURY PRESS FIRST HARPERCOLLINS EDITION PUBLISHED IN 1993 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McKenna, Terence K., 1946- The Invisible landscape : mind, hallucinogens, and the I ching / Terence McKenna and Dennis McKenna.—1st HarperCollins ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-06-250635-8 (acid-free paper) 1. I ching. 2. Mind and body. 3. Shamanism. I. Oeric, O. N. II. Title. BF161.M47 1994 133—dc2o 93-5195 CIP 01 02 03 04 05 RRD(H) 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 In Memory of our dear Mother Thus were the stars of heaven created like a golden chain To bind the Body of Man to heaven from falling into the Abyss. -

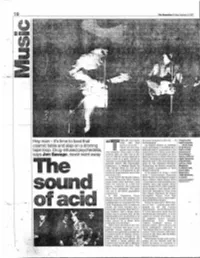

It's Time to Beat That Cosmic Tabla and Slap On

UllN ofT your mind. the Rame exlstence to the nrnl ... of l\>lpplll1;lthe Hey man - it's time to beat that relax and float the beginning". light ' __ aile downstream.··· An explicit assault on contemp- ••• "'"kFloyd cosmic tabla and slap on a droning There are few com- orary perrept ion, a manifesto for a .tAII5-ftlnt •• tape Drug-infused psychedelia, mands more simple different kiml of consciousness. the Hallin IDe!! loop, and evocative. They came to .John track is timoless. Thirty years 1:\trr, (.bo .•.•••nd says Jon Savage, never went away Lennon nfter an LSD trip at the its influence is everywhere in rock: Kul.Shak.r turn of 196.')/66, during which h("d there ClTC echoes in Oasts's Mornlng (below left); tar used a hook as a RUide. Edited hy Glory ("Ii$tcning to the sound of my right, 1Ir." 'or Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner and Iavour-lte tunc"). the accented drum Paych~.lIe Richard Alpert. The Psychedelic. loops of The Chemical Brothers' Circus, 1903 Experience; A Manual Based On Sett ing Sun. tho Eastern sonorities (D""I.y's, The Tibetan Book Of The Dend and psychic propaganda of Kula London); and, ,.he aimed to givl" a framework to the Shaker's album K, I"•• tri\lhl. explicitly experimental use or this in its equat ion of druas + aurnl Sp.etrum. new (Iru)!.I.sn. Inops = trnnsrondenco. Tomorrow 1089 CUe lIVen, At the end of The Bcatles' album. Never Knows also prefig\.u"f'$ ((\C1:tY's ~~_J _ Revolver; Tomorrow Never Knows dance culture. -

![My Own Life[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4751/my-own-life-1-934751.webp)

My Own Life[1]

My Own Life[1] Dorion Cairns I was born July 4th, 1901, in the village of Contoocook, in the town of Hopkinton, New Hampshire. My father, James George Cairns, was the pastor of the Methodist Church in Contoocook, and I was the first child of my parents. During my first three and a half years of life, my father moved from one place to another as pastor of Methodist Churches in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. My brother, Stewart Scott Cairns, currently Professor of Mathematics at the University of Illinois, was born May 8th, 1904. My father felt that there was no future for a young minister in New England, and he decided to move his family—which consisted of my mother, my brother and me—to California. He shipped all of our family goods, all of our furniture and things, to California on the very day of the San Francisco Earthquake, or “Fire,” as they like to call it in San Francisco. The California Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church at that time controlled what was called the “Utah Mission.” This was a mission to Mormon Territory, needless to say. My father, since there were so many people of longer standing in the California Conference who had no churches left owing to the earthquake, was given a church in Utah Mission, in Salt Lake City itself. It was there in 1907 that my sister Mary, who is the wife of James Wilkinson Miller, currently Professor of Philosophy at McGill University in Montreal, was born. When they wanted to transfer my father from this little church in Salt Lake City to a church or mission in Provo, Utah, my father went and looked at the set-up in Provo, and he came back, and it was the first time I had seen a grown man cry. -

The Manifold Concept of the Lifeworld. Husserl and His Posterity

Doctorado en Filosofía The Manifold Concept of the lifeworld. Husserl and his posterity Academic Term 2nd Semester 2021 Credits 6 Calendar Once-a-week sessions, Tuesdays, 15.30-18.30; September 28 – December 14 Office hours Fridays, 17.00-18.00 Profesor Ovidiu Stanciu Mail [email protected] DESCRIPTION The concept of the world has played a significant role in the phenomenological tradition. By redefining the meaning of the world and proposing a “natural concept of the world” (natürliche Weltbegriff) or a concept of the lifeworld (Lebenswelt), phenomenology was able to make clear the peculiarity of its own undertaking against competing philosophical directions such as Neo-Kantianism, logical positivism or neutral monism (Whitehead, W. James). The first major formulation of the concept of lifeworld can be traced back to Husserl’s last writings, namely the ‘‘Crisis’’-texts. This course aims at unpacking the various ramifications and levels of analysis entailed in this question and at proposing a critical discussion of the ambiguities the concept of “life-world” contains. The basic claim Husserl (and the subsequent phenomenological tradition) is issuing is that although the world is never an immediate object of experience, although it cannot be experienced in a straightforward way as we experience things in the world, it is yet a built-in structure and a necessary ingredient of every experience. In and through each of our particular perceptions and actions we experience not only particular things but also of the world as their ultimate horizon. The correlative thesis is that every experience has an intuitive core and a non-thematic background, which properly understood is that of the world. -

Kant, Neo-Kantianism, and Phenomenology Sebastian Luft Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Philosophy Faculty Research and Publications Philosophy, Department of 7-1-2018 Kant, Neo-Kantianism, and Phenomenology Sebastian Luft Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Oxford Handbook of the History of Phenomenology (07/18). DOI. © 2018 Oxford University Press. Used with permission. Kant, Neo-Kantianism, and Phenomenology Kant, Neo-Kantianism, and Phenomenology Sebastian Luft The Oxford Handbook of the History of Phenomenology Edited by Dan Zahavi Print Publication Date: Jun 2018 Subject: Philosophy, Philosophy of Mind, History of Western Philosophy (Post-Classical) Online Publication Date: Jul 2018 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198755340.013.5 Abstract and Keywords This chapter offers a reassessment of the relationship between Kant, the Kantian tradi tion, and phenomenology, here focusing mainly on Husserl and Heidegger. Part of this re assessment concerns those philosophers who, during the lives of Husserl and Heidegger, sought to defend an updated version of Kant’s philosophy, the neo-Kantians. The chapter shows where the phenomenologists were able to benefit from some of the insights on the part of Kant and the neo-Kantians, but also clearly points to the differences. The aim of this chapter is to offer a fair evaluation of the relation of the main phenomenologists to Kant and to what was at the time the most powerful philosophical movement in Europe. Keywords: Immanuel Kant, neo-Kantianism, Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Marburg School of neo-Kantian ism 3.1 Introduction THE relation between phenomenology, Kant, and Kantian philosophizing broadly con strued (historically and systematically), has been a mainstay in phenomenological re search.1 This mutual testing of both philosophies is hardly surprising given phenomenology’s promise to provide a wholly novel type of philosophy. -

Music, Culture, and the Rise and Fall of the Haight Ashbury Counterculture

Zaroff 1 A Moment in the Sun: Music, Culture, and the Rise and Fall of the Haight Ashbury Counterculture Samuel Zaroff Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, Georgetown University Advisor: Professor Maurice Jackson Honors Program Chairs: Professor Katherine Benton-Cohen and Professor Alison Games 6 May 2019 Zaroff 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 Historiography 8 Chapter I: Defining the Counterculture 15 Protesting Without Protest 20 Cultural Exoticism in the Haight 24 Chapter II: The Music of the Haight Ashbury 43 Musical Exoticism: Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit” 44 Assimilating African American Musical Culture: Big Brother and the Holding Company’s “Summertime” 48 Music, Drugs, and Hendrix: “Purple Haze” 52 Protesting Vietnam: Country Joe and the Fish’s “I-Feel-Like-I’m Fixin’-to-Die-Rag” 59 Folk, Nature, and the Grateful Dead: “Morning Dew” and the Irony of Technology 62 Chapter III: The End of the Counterculture 67 Overpopulation 67 Commercialization 72 Hard Drugs 74 Death of the Hippie Ceremony 76 “I Know You Rider”: Music of the End of the Counterculture 80 Violence: The Altamont Speedway Free Festival 85 Conclusion 90 Appendix 92 Bibliography 94 Zaroff 3 Acknowledgements Thank you, Professor Benton-Cohen and Professor Jackson, for your guidance on this thesis. Thank you, Mom, Dad, Leo, Eliza, Roxanne, Daniela, Ruby, and Boo for supporting me throughout. Lastly, thank you Antine and Uncle Rich for your wisdom and music. I give permission to Lauinger Library to make this thesis available to the public. Zaroff 4 Introduction From 1964 to 1967, the Haight Ashbury district of San Francisco experienced one of the most significant and short-lived cultural moments of twentieth century America. -

Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967 James M. Maynard Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, and the American Popular Culture Commons Recommended Citation Maynard, James M., "Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/170 Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967 Jamie Maynard American Studies Program Senior Thesis Advisor: Louis P. Masur Spring 2012 1 Table of Contents Introduction..…………………………………………………………………………………4 Chapter One: Developing the niche for rock culture & Monterey as a “savior” of Avant- Garde ideals…………………………………………………………………………………...7 Chapter Two: Building the rock “umbrella” & the “Hippie Aesthetic”……………………24 Chapter Three: The Yin & Yang of early hippie rock & culture—developing the San Francisco rock scene…………………………………………………………………………53 Chapter Four: The British sound, acid rock “unpacked” & the countercultural Mecca of Haight-Ashbury………………………………………………………………………………71 Chapter Five: From whisperings of a revolution to a revolution of 100,000 strong— Monterey Pop………………………………………………………………………………...97 Conclusion: The legacy of rock-culture in 1967 and onward……………………………...123 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………….128 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..131 2 For Louis P. Masur and Scott Gac- The best music is essentially there to provide you something to face the world with -The Boss 3 Introduction: “Music is prophetic. It has always been in its essence a herald of times to come. Music is more than an object of study: it is a way of perceiving the world. -

LUCY PDF ONLINE.Indd

Astro-Chthonic Anomaly Exoskeleton of the flabby body Pulpy sack, cowering in a UFO Invertebrate inebriation Egg and runny stuff Jism network White spunk running down black rubber Battery ooze The old ones and their young-uns Amorphous appendage Ectoplasm sculpture Mike Kelley, Minor Histories, 2004 I lost... you know, I lost another day, what I lost was gold, golden notions... erased.. smoke dreams, phantoms... Communion, dir. Philippe Mora, 1989 Somewhere there the land is hollow. Penda’s Fen, dir. Alan Clarke, 1974 Through a vertiginous core sample from the astral to the subterranean, through veiny portals of extraocular musculature, the line of sight descends from murky air that’s filled with spectres of unknown beings. It passes over lithic monuments and pastoral wastes, down through the windblown grassy tufts, mossy materials, compost, loam and grit. It bores into the shell of the earth, down through endless geologic strata, into the caverns of the chthonic* imaginary. Within the lurid, conchological walls of this dank, clammy basement, a lucid dream-vision of an extra-terrestrial serpent uncoils from an incubation. A temporal anomaly in the crypt. (CREAKING) (INAUDIBLE) (CREAKING CONTINUES) (CHIMING) (EARS RINGING) (MUFFLED SPEECH) I cannot hear! (EARS RINGING) Oh! (GROANING) Please! (CHANTING IN THE DISTANCE)1 ‘All of us gaze into that “dark glass” in which the dark myth takes shape, adumbrating the invisible truth. In this glass the eyes of the spirit glimpse an image which we call the self, fully conscious of the fact that it is an anthropomorphic image which we have merely named but not explained.’ 2 * The term “chthonic” comes from the Greek chthonios, meaning of, in, or under the earth.