284 Erik Davis Highweirdness Emerged in June, 2019 As a Joint Publication of MIT and Strange Attractorpress.1Thispublishingallia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

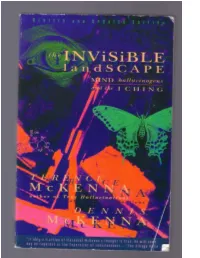

THE INVISIBLE LANDSCAPE: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching

To inquire about Time Wave software in both Macintosh and DOS versions please contact Blue Water Publishing at 1-800-366-0264. fax# (503) 538-8485. or write: P.O. Box 726 Newberg, OR 97132 Passage from The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, edited by David V. Erdman. Commentary by Harold Bloom. Copyright © 1965 by David V. Erdman and Harold Bloom. Published by Doubleday Company, Inc. Used by permission. THE INVISIBLE LANDSCAPE: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching. Copyright © 1975, 1993 by Dennis J. McKenna and Terence K. McKenna. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022. Interior design by Margery Cantor and Jaime Robles FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1975 BY THE SEABURY PRESS FIRST HARPERCOLLINS EDITION PUBLISHED IN 1993 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McKenna, Terence K., 1946- The Invisible landscape : mind, hallucinogens, and the I ching / Terence McKenna and Dennis McKenna.—1st HarperCollins ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-06-250635-8 (acid-free paper) 1. I ching. 2. Mind and body. 3. Shamanism. I. Oeric, O. N. II. Title. BF161.M47 1994 133—dc2o 93-5195 CIP 01 02 03 04 05 RRD(H) 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 In Memory of our dear Mother Thus were the stars of heaven created like a golden chain To bind the Body of Man to heaven from falling into the Abyss. -

LUCY PDF ONLINE.Indd

Astro-Chthonic Anomaly Exoskeleton of the flabby body Pulpy sack, cowering in a UFO Invertebrate inebriation Egg and runny stuff Jism network White spunk running down black rubber Battery ooze The old ones and their young-uns Amorphous appendage Ectoplasm sculpture Mike Kelley, Minor Histories, 2004 I lost... you know, I lost another day, what I lost was gold, golden notions... erased.. smoke dreams, phantoms... Communion, dir. Philippe Mora, 1989 Somewhere there the land is hollow. Penda’s Fen, dir. Alan Clarke, 1974 Through a vertiginous core sample from the astral to the subterranean, through veiny portals of extraocular musculature, the line of sight descends from murky air that’s filled with spectres of unknown beings. It passes over lithic monuments and pastoral wastes, down through the windblown grassy tufts, mossy materials, compost, loam and grit. It bores into the shell of the earth, down through endless geologic strata, into the caverns of the chthonic* imaginary. Within the lurid, conchological walls of this dank, clammy basement, a lucid dream-vision of an extra-terrestrial serpent uncoils from an incubation. A temporal anomaly in the crypt. (CREAKING) (INAUDIBLE) (CREAKING CONTINUES) (CHIMING) (EARS RINGING) (MUFFLED SPEECH) I cannot hear! (EARS RINGING) Oh! (GROANING) Please! (CHANTING IN THE DISTANCE)1 ‘All of us gaze into that “dark glass” in which the dark myth takes shape, adumbrating the invisible truth. In this glass the eyes of the spirit glimpse an image which we call the self, fully conscious of the fact that it is an anthropomorphic image which we have merely named but not explained.’ 2 * The term “chthonic” comes from the Greek chthonios, meaning of, in, or under the earth. -

Timothy Leary's Legacy and the Rebirth of Psychedelic Research

Timothy Leary’s legacy and the rebirth of psychedelic research The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lattin, Don. 2019. Timothy Leary’s legacy and the rebirth of psychedelic research. Harvard Library Bulletin 28 (1), Spring 2017: 65-74. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41647383 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Timothy Leary’s Legacy and the Rebirth of Psychedelic Research Don Lattin imothy Leary, the self-proclaimed “high priest” of the psychedelic counterculture of the 1960s, issued countless proclamations and prophecies Tduring his three decades in the public eye. Here’s one he made in San Francisco in 1965, just a couple years afer the fellows at Harvard College dismissed him as a lecturer in clinical psychology:1 “I predict that within one generation we will have across the bay in Berkeley a Department of Psychedelic Studies. Tere will probably be a dean of LSD.» Two generations later, the University of California at Berkeley has yet to establish its Department of Psychedelic Studies. But, as is ofen the case with Timothy Leary, the high priest was half right in his prediction that mainstream academia would someday rediscover the value of psychedelic research. Harvard does not have a dean of LSD, but it now has something called “Te LSD Library.” Tat would be the Ludlow-Santo Domingo Library, an intoxicating collection housed at Harvard Library that includes many items from the Timothy Leary archive. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 329 4th International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2019) Altered States of Consciousness and New Horizons of the Sacred* Philipp Tagirov Department of Social Philosophy Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN) Moscow, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Through psychedelics we are learning that God is not an idea, God is a lost continent in the human mind. Terence McKenna, Food of the gods we’re so poor we can’t even pay attention Kmfdm, Dogma Abstract—The article studies the complex and rather goes through the greatest existential intensities of modernity equivocal discourse set around the altered states of — and we follow him. Violence in the name of the sacred, consciousness and so-called “emerging scientific paradigm” being one of such intensities, is based on the making the which claims to return to human existence a certain supreme Radical other (the Monstrous other) of another human being transcendental meaning that could help rebuilding a universal [1], thus demonizing the opponent [2]. The current study symbolic space, and thus return a man himself to the sacred addresses different kind of intensities when a person striving reality. The psychedelic trend unites concepts and approaches for the Radical other (the Divine other) radically transforms that differ significantly from each other both in their degree of himself. And radically transforms our usual ideas about proximity to academic science and in their conclusions human being. regarding the dominant mental paradigm. However, representatives of this trend, despite all the differences, stand The American 1960s are known as the “golden 60s”, like together for that the so-called altered states of consciousness The Golden Age. -

Narrating the Unspeakable Making Sense of Psychedelic Experiences in Drug Treatment

ISSN: 2535-3241 Vol. 3, No. 2 (2019): 116-140 https://doi.org/10.5617.7365 Article Narrating the Unspeakable Making Sense of Psychedelic Experiences in Drug Treatment Shana Harris University of Central Florida Abstract The use of psychedelic substances has been described as an ‘unspeakable primary experi- ence,’ one that is personal and ultimately indescribable. The ineffable quality of such an experience, however, does not prohibit or invalidate attempts to explain it. The struggle to narrate one’s experience is instead an important endeavor. But, how does narration work if the psychedelic experience is truly unspeakable? What kind of narratives are possible? What kinds of narrative work do psychedelics foreclose? This article addresses these ques- tions by analyzing narratives generated about the use of psychedelics for drug treatment. Drawing on 16 months of ethnographic research at drug treatment centers in Baja Cali- fornia, Mexico, this article examines what narration looks like in the context of a psy- chedelic-based drug treatment modality. It pays particular attention to how people in treatment retell – or struggle to retell – their experiences with psychedelics to make sense of them and then articulate them for the researcher. I argue that psychedelic experiences pose a unique challenge for the anthropological study of these substances, particularly their therapeutic use. I show how these experiences resist narrativization in multiple ways, presenting both ethnographic and epistemological obstacles to the production of anthro- pological knowledge. Keywords addiction, drug treatment, narrative, psychedelics, Mexico Introduction Ethnobotanist and psychedelic advocate Terence McKenna describes the use of psychedelic substances as an ‘unspeakable primary experience,’ one that is ‘pri- vate, personal … and ultimately unspeakable’ (McKenna 1991, 257). -

Terence Mckennaand Death

maps bulletin • volume xx number 1 maps bulletin • volume xx number 1 49 Terence McKenna and Death By Alexander Beiner & David Jay Brown To follow is a short summary of the late ethnobotanist Terence McK- include entities performing experiments on the individual, enna’s views on death. An except from the interview that I did with finding oneself in a ‘nursery’ environment and a general ‘realer Terence in 1989 is followed by Alexander Beiner’s summary of a talk than real’ sensation surrounding the whole process. To people thatDavid: Terence Do you gave have at the any Esalen thoughts Institute on what happens to human who study the reports of UFO abductees this may sound very inconsciousness 1994. after biological death? familiar. Indeed, Rick Strassman, Graham Hancock and others have convincingly elucidated a strong phenomenological link between these seemingly distinct experiences. It is understandable that, given these crossovers, many Terence: I’ve thought about it. When I think about it I feel people see DMT entities as extraterrestrial intelligences. McK- like I’m on my own. The Logos doesn’t want to help here, and enna himself sometimes seemed to lean toward this conclu- has nothing to say to me on the subject of biological death. sion, so it might then come as a surprise to hear him muse What I imagine happens is that for the self time begins to later in the same talk: “I think in service of parsimony... these flow backwards; even before death, the act of dying is the act [entities] must be human souls.” This statement raises some of reliving an entire life, and at the end of the dying process, beautiful and eerie prospects. -

“Stoned Ape Theory” on the Origins of Consciousness and Language: Implications for Language Pedagogy

Journal of Conscious Evolution Volume 16 Issue 1 Articles from an Art and Consciousness Article 6 Class 11-7-2020 An Exploration of Linguistic Relativity Theory for Consideration of Terence McKenna’s “Stoned Ape Theory” on the Origins of Consciousness and Language: Implications for Language Pedagogy Nicole Lopez California Institute of Integral Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Cognition and Perception Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, Social Psychology Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Lopez, Nicole (2020) "An Exploration of Linguistic Relativity Theory for Consideration of Terence McKenna’s “Stoned Ape Theory” on the Origins of Consciousness and Language: Implications for Language Pedagogy," Journal of Conscious Evolution: Vol. 16 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal/vol16/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conscious Evolution by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, -

Managed Madness Gabriel Roberts [email protected]

University of Washington Tacoma UW Tacoma Digital Commons MAIS Projects and Theses School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Spring 2019 Managed Madness Gabriel Roberts [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/ias_masters Part of the Other Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Gabriel, "Managed Madness" (2019). MAIS Projects and Theses. 59. https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/ias_masters/59 This Open Access (no embargo, no restriction) is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at UW Tacoma Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAIS Projects and Theses by an authorized administrator of UW Tacoma Digital Commons. Running head: MANAGED MADNESS 1 Managed Madness: Foucault & McKenna’s Use of Madness and The Psychedelic Experience As A Tool of Critique Gabriel D. Roberts A proposal submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master's Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies Gabriel D. Roberts Proposed Supervisor Dr. Asao Inoue - (MAIS) Proposed Reader(s) Dr. Ingrid Walker - (IAS) MANAGED MADNESS 2 Table of contents Author’s note…………………………………………………………………………....3 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………...8 Chapter 1: A philosopher’s new set of eyes…………………………………………....14 Chapter 2: Foucault’s perspective on Madness………………………………………...18 Chapter 3: Terence McKenna & The Psychedelic Lens……………………………......28 Chapter 4: Interviews…………………………………………………………………...39 Chapter 5: Final Thoughts……………………………………………………………...52 References……………………………………………………………………………...60 MANAGED MADNESS 3 Author Note Special thanks are in order to Dr. Asao Inoue who has shown me the power of words and how they shape the reality that we share. His insights on pedagogy, classical rhetoric and writing have enabled me to greatly expand my own knowledge and skill. -

Terence Mckenna Bibliography Video Media John Hazard

Terence McKenna Bibliography This compilation is © 2000–2011 Chris Mays. Return to Table of Contents Video Media John Hazard (2011) A conversation with Terence McKenna. Hour long video interview conducted "in the jungle"—probably McKenna's residence in Hawai’i—in October, 1998, and ranging over many familiar topics, including Novelty, the I Ching, the strange attractor and the nature of time, matter and information. More information: http://www.hazarddp.com/?page_id=2. Sharron Rose (2008) Timewave 2013 The Odyssey II: The Future is Now. Sacred Mysteries, Ashland OR. More information: http://www.sacredmysteries.com/public/138.cfm. Sheldon Rocklin, Maxine Rocklin, Morgan Harris and Terence K McKenna (2008) Alchemical Dream: Rebirth of the Great Work. Mystic Fire, From the film's website: “Originally titled Coincidencia Oppositorum: The Unity of Opposites and filmed in Prague with Terence portraying his usual erudite rendition of the Irish Bard, this filmed classic takes us on a journey into the alchemical renaissance of King Frederick V and his wife Queen Elizabeth of Bohemia”. More information: http://www.sacredmysteries.com/public/147.cfm. Gary Tarpinian (2007) Doomsday 2012: The End of Days. Decoding The Past, Morningstar Entertainment, Burbank CA. Daniel Pinchbeck [2012: THE RETURN OF QUETZALCOATL (2006)] and his publisher Mitch Horowitz are heard in a brief segment about McKenna's Time Wave Zero prophecy (19:56-21:48) in this History Channel documentary on 2012. Terence K. McKenna and Mitchell Jay Rabin (2006) Toward the End of History: Terence McKenna. Penny Price Media, Staatsburg NY. Mike Kawitzky (2005) Cognition Factor. Schwann All Media, A forthcoming independent film by South African Schwann Cybershaman. -

Terence Mckenna the Importance of Human Beings

Terence McKenna The Importance of Human Beings Presented at ??? Podcast available for free download at: http://www.matrixmasters.net/blogs/?p=297 What I wanted to talk about tonight, simply because it’s the thing that is moving me to the edge of my chair at the moment, is – I called the talk Eros and the Eschaton, and what I could have called it is Eros and the Eschaton: What Science Forgot, because somebody asked me recently, “Is there any permission to hope?” More specifically, is there any permission for smart people to hope?! – I mean, it’s easy to hope if you’re stupid! – but is there any basis for intelligent people to hope? And I wanted to deal with that, because I think so. I mean, it was to me… Eros and the Eschaton – these are the two areas that I think compromise the old paradigm and give permission to hope; and strangely, neither of these words is that well known, which gives you a measure of how completely the dominator position has squelched, subverted and downplayed any opposition to its worldview. Eros, we know about, in some kind of devalued, schticky kind of glitzy way, because we get it in the eroticisation of media and society. But really, what Eros means in the Greek sense is a kind of unity of nature, a kind of all-pervasive order that bridges one ontological level to another. This is not permitted in the official worldview of our civilisation, which is science. The world of inorganic chemistry is not thought to make any statement about the organic world, and the organic world is not thought to be extrapolatable into the world of culture and thought. -

Terence Mckenna's Jungian Psychedelic Ufology

Inner Space/Outer Space: Terence McKenna’s Jungian Psychedelic Ufology ___________________________________________________________________ Christopher Partridge ABSTRACT: This article discusses the relationship between “inner space” (the mind/consciousness) and perceptions of “outer space” (the extraterrestrial) in Western psychedelic cultures. In particular, it analyses the writings and lectures of Terence McKenna, the most influential psychedelic thinker since the 1960s. Assimilating a broad range of ideas taken from esotericism, shamanism, and science fiction, McKenna became the principal architect of an occult theory of psychedelic experiences referred to here as “psychedelic ufology.” The article further argues that McKenna was formatively influenced by the ideas of Carl Jung and that, as such, subsequent psychedelic ufology tends to be Jungian. KEYWORDS: Terence McKenna, Carl Jung, psychedelic ufology, UFOs, hallucinogens, shamanism, gnosis During a lecture in Switzerland in 1995, the American psychedelic thinker Terence McKenna (1946-2000) claimed that if a person gave him “15 minutes of [their] life” (i.e. if he was given the time to administer an hallucinogen) he could guarantee “a 20% chance of meeting aliens—and the odds go up to maybe 40% if you increase the dose!”1 While this can be interpreted as a playful comment about induced hallucinations rather than anything more profound, this would be a mistake. For McKenna it was no coincidence that “UFO contact [was]… the motif most frequently mentioned by people who take psilocybin recreationally.”2 “At active levels, psilocybin induces visionary ideation of spacecraft, alien creatures, and alien information. There is a general futuristic, science fiction quality to the psilocybin experience that seems to originate from the same place as the modern myth of the UFO.”3 He is not alone in claiming this. -

Tryptamine Hallucinogens and Consciousness

Tryptamine Hallucinogens and Consciousness By Terence McKenna A talk given at the Lilly/Goswami Conference on Consciousness and Quantum Physics at Esalen, December 1983. It was to be the first of many lectures at Esalen Institute on the Big Sur Coast of California. Published 1992 in The Archaic Revival.1 There is a very circumscribed place in organic nature that has, I think, important implications for students of human nature. I refer to the tryptophan-derived hallucino- gens dimethyltryptamine (DMT), psilocybin, and a hybrid drug that is in aboriginal use in the rain forests of South America, ayahuasca. This latter is a combination of dimethyltryptamine and a monoamine oxidase inhibitor that is taken orally. It seems appropriate to talk about these drugs when we discuss the nature of consciousness; it is also appropriate when we discuss quantum physics. It is my interpretation that the major quantum mechanical phenomena that we all experience, aside from waking consciousness itself, are dreams and hallucinations. These states, at least in the restricted sense that I am concerned with, occur when the large amounts of various sorts of radiation conveyed into the body by the senses are restricted. Then we see interior images and interior processes that are psycho-physical. These processes definitely arise at the quantum mechanical level. It’s been shown by John Smythies, Alexander Shulgin, and others that there are quantum mechanical correlates to hallucinogenesis. In other words, if one atom on the molecular ring of an inactive compound is moved, the compound becomes highly active. To me this is a perfect proof of the dynamic linkage at the formative level between quantum mechanically described matter and mind.