Narrating the Unspeakable Making Sense of Psychedelic Experiences in Drug Treatment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

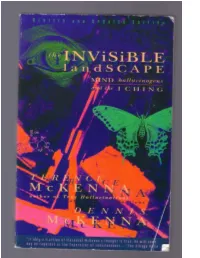

THE INVISIBLE LANDSCAPE: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching

To inquire about Time Wave software in both Macintosh and DOS versions please contact Blue Water Publishing at 1-800-366-0264. fax# (503) 538-8485. or write: P.O. Box 726 Newberg, OR 97132 Passage from The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, edited by David V. Erdman. Commentary by Harold Bloom. Copyright © 1965 by David V. Erdman and Harold Bloom. Published by Doubleday Company, Inc. Used by permission. THE INVISIBLE LANDSCAPE: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching. Copyright © 1975, 1993 by Dennis J. McKenna and Terence K. McKenna. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022. Interior design by Margery Cantor and Jaime Robles FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1975 BY THE SEABURY PRESS FIRST HARPERCOLLINS EDITION PUBLISHED IN 1993 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McKenna, Terence K., 1946- The Invisible landscape : mind, hallucinogens, and the I ching / Terence McKenna and Dennis McKenna.—1st HarperCollins ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-06-250635-8 (acid-free paper) 1. I ching. 2. Mind and body. 3. Shamanism. I. Oeric, O. N. II. Title. BF161.M47 1994 133—dc2o 93-5195 CIP 01 02 03 04 05 RRD(H) 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 In Memory of our dear Mother Thus were the stars of heaven created like a golden chain To bind the Body of Man to heaven from falling into the Abyss. -

![The Use of Iboga[Ine] in Equatorial African Ritual Context And](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9402/the-use-of-iboga-ine-in-equatorial-african-ritual-context-and-1269402.webp)

The Use of Iboga[Ine] in Equatorial African Ritual Context And

——Chapter 13—— "RETURNING TO THE PATH": THE USE OF IBOGA[INE] IN AN EQUATORIAL AFRICAN RITUAL CONTEXT AND THE BINDING OF TIME, SPACE, AND SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS James W. Fernandez Renate L. Fernandez Department of Anthropology The University of Chicago Chicago, IL 60637 I. Introduction.................................................................................................................. II. Time Binding in Professional and Religious Worlds .................................................. III. Pathologies of the Colonial World and the Role of Iboga in Religious Movements .................................................................................................. IV. A Comparison of the Introduction and Maintenance of Iboga Use in Bwiti and in Therapeutic Settings (INTASH) ............................................................. V. The Contemporary Ethnography of Iboga Use ........................................................... VI. Conclusions.................................................................................................................. Endnotes....................................................................................................................... References.................................................................................................................... I. Introduction In this chapter the authors, a cultural (JWF) and a biocultural anthropologist (RLF), reexamine their late 1950s ethnographic work among iboga(ine) users in Equatorial Africa in light of Western -

“Micro-Flood” Dosing Iboga with Cannabis Piercing the Veil Between the Conscious and Subconscious

“Micro-Flood” Dosing Iboga with Cannabis Piercing the Veil Between the Conscious and Subconscious "Micro-Flood" Dosing Iboga with Cannabis Disclaimer • This information is being presented for purposes of harm reduction and education • I do not condone or advocate the use of any illicit substances, or illegal activity of any kind • Iboga, like other plant medicines should not be taken before serious consideration and research into possible health risks or contraindications • Advice or opinions on the use of Iboga is provided for the benefit of those who have adequately researched such risks, and assumes anyone using this substance will do so in a jurisdiction where neither its possession nor consumption would constitute a violation of any law. "Micro-Flood" Dosing Iboga with Cannabis Iboga/Ibogaine Medical Risks and Contraindications ::::PARTIAL LIST:::: • Heart conditions or defects • Epilepsy or seizure disorders (especially QT prolonging) • History of blood clots • Psychiatric disorders • Diabetes (uncontrolled) • Impaired liver or kidney function • High/Low Blood Pressure • SSRIs, psychoactive medications, • Cerebella Disfunction drug replacement therapy drugs (methadone, buprenorphine) • Emphysema NOTE: Cannabis can lower blood pressure, presenting another contraindication for anyone with cardiac abnormalities. "Micro-Flood" Dosing Iboga with Cannabis “Iboga is the vehicle that allows you to sit with yourself long enough to realize that thing you are afraid of is an illusion.” Tricia Eastman, Entheonation.com "Micro-Flood" Dosing Iboga -

LUCY PDF ONLINE.Indd

Astro-Chthonic Anomaly Exoskeleton of the flabby body Pulpy sack, cowering in a UFO Invertebrate inebriation Egg and runny stuff Jism network White spunk running down black rubber Battery ooze The old ones and their young-uns Amorphous appendage Ectoplasm sculpture Mike Kelley, Minor Histories, 2004 I lost... you know, I lost another day, what I lost was gold, golden notions... erased.. smoke dreams, phantoms... Communion, dir. Philippe Mora, 1989 Somewhere there the land is hollow. Penda’s Fen, dir. Alan Clarke, 1974 Through a vertiginous core sample from the astral to the subterranean, through veiny portals of extraocular musculature, the line of sight descends from murky air that’s filled with spectres of unknown beings. It passes over lithic monuments and pastoral wastes, down through the windblown grassy tufts, mossy materials, compost, loam and grit. It bores into the shell of the earth, down through endless geologic strata, into the caverns of the chthonic* imaginary. Within the lurid, conchological walls of this dank, clammy basement, a lucid dream-vision of an extra-terrestrial serpent uncoils from an incubation. A temporal anomaly in the crypt. (CREAKING) (INAUDIBLE) (CREAKING CONTINUES) (CHIMING) (EARS RINGING) (MUFFLED SPEECH) I cannot hear! (EARS RINGING) Oh! (GROANING) Please! (CHANTING IN THE DISTANCE)1 ‘All of us gaze into that “dark glass” in which the dark myth takes shape, adumbrating the invisible truth. In this glass the eyes of the spirit glimpse an image which we call the self, fully conscious of the fact that it is an anthropomorphic image which we have merely named but not explained.’ 2 * The term “chthonic” comes from the Greek chthonios, meaning of, in, or under the earth. -

Timothy Leary's Legacy and the Rebirth of Psychedelic Research

Timothy Leary’s legacy and the rebirth of psychedelic research The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lattin, Don. 2019. Timothy Leary’s legacy and the rebirth of psychedelic research. Harvard Library Bulletin 28 (1), Spring 2017: 65-74. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41647383 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Timothy Leary’s Legacy and the Rebirth of Psychedelic Research Don Lattin imothy Leary, the self-proclaimed “high priest” of the psychedelic counterculture of the 1960s, issued countless proclamations and prophecies Tduring his three decades in the public eye. Here’s one he made in San Francisco in 1965, just a couple years afer the fellows at Harvard College dismissed him as a lecturer in clinical psychology:1 “I predict that within one generation we will have across the bay in Berkeley a Department of Psychedelic Studies. Tere will probably be a dean of LSD.» Two generations later, the University of California at Berkeley has yet to establish its Department of Psychedelic Studies. But, as is ofen the case with Timothy Leary, the high priest was half right in his prediction that mainstream academia would someday rediscover the value of psychedelic research. Harvard does not have a dean of LSD, but it now has something called “Te LSD Library.” Tat would be the Ludlow-Santo Domingo Library, an intoxicating collection housed at Harvard Library that includes many items from the Timothy Leary archive. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 329 4th International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2019) Altered States of Consciousness and New Horizons of the Sacred* Philipp Tagirov Department of Social Philosophy Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN) Moscow, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Through psychedelics we are learning that God is not an idea, God is a lost continent in the human mind. Terence McKenna, Food of the gods we’re so poor we can’t even pay attention Kmfdm, Dogma Abstract—The article studies the complex and rather goes through the greatest existential intensities of modernity equivocal discourse set around the altered states of — and we follow him. Violence in the name of the sacred, consciousness and so-called “emerging scientific paradigm” being one of such intensities, is based on the making the which claims to return to human existence a certain supreme Radical other (the Monstrous other) of another human being transcendental meaning that could help rebuilding a universal [1], thus demonizing the opponent [2]. The current study symbolic space, and thus return a man himself to the sacred addresses different kind of intensities when a person striving reality. The psychedelic trend unites concepts and approaches for the Radical other (the Divine other) radically transforms that differ significantly from each other both in their degree of himself. And radically transforms our usual ideas about proximity to academic science and in their conclusions human being. regarding the dominant mental paradigm. However, representatives of this trend, despite all the differences, stand The American 1960s are known as the “golden 60s”, like together for that the so-called altered states of consciousness The Golden Age. -

284 Erik Davis Highweirdness Emerged in June, 2019 As a Joint Publication of MIT and Strange Attractorpress.1Thispublishingallia

284 Book Reviews Erik Davis, High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies. Estonia: Strange Attractor Press / MIT Press, 2019. ix–545 p. ISBN: 9781907222870. High Weirdness emerged in June, 2019 as a joint publication of MIT and Strange Attractor Press.1 This publishing alliance is reflected in Davis’ attempt to appeal to both an academic and non-academic audience, the former a renowned aca- demic press, the latter an independent publishing house dedicated to an eclec- tic mixture of esoteric, pulp, and underground culture. In terms of design, the volume definitely leans towards the aesthetics of Strange Attractor: the front cover of High Weirdness depicts UFO-like mushrooms beaming a ray of light into the centre of a luminous triangle—a nod to the occultural density of the book’s subject matter. High Weirdness presents a history of three influential countercultural fig- ures in 1970s America—Terence McKenna, Robert Anton Wilson, and Philip K. Dick.The study focuses on a selection of visionary experiences the three men underwent between the years 1971–1974. Davis investigates these by means of a close reading of the individual accounts, and places these within their histori- cal and discursive contexts. However, Davis retains an openness regarding the ultimate status of his subjects’ visions, auditions, and alleged revelations. Plac- ing himself within the Pragmatist lineage of William James, Davis rejects any form of reductionism. His intellectual investigations are merely to be regarded as approximations, never claiming full grasp of the ontological provenance of the three men’s experiences. This methodological ethos is furthermore sub- stantiated in one of the opening quotes in High Weirdness by William James: ‘Something always escapes’ (xi). -

Terence Mckennaand Death

maps bulletin • volume xx number 1 maps bulletin • volume xx number 1 49 Terence McKenna and Death By Alexander Beiner & David Jay Brown To follow is a short summary of the late ethnobotanist Terence McK- include entities performing experiments on the individual, enna’s views on death. An except from the interview that I did with finding oneself in a ‘nursery’ environment and a general ‘realer Terence in 1989 is followed by Alexander Beiner’s summary of a talk than real’ sensation surrounding the whole process. To people thatDavid: Terence Do you gave have at the any Esalen thoughts Institute on what happens to human who study the reports of UFO abductees this may sound very inconsciousness 1994. after biological death? familiar. Indeed, Rick Strassman, Graham Hancock and others have convincingly elucidated a strong phenomenological link between these seemingly distinct experiences. It is understandable that, given these crossovers, many Terence: I’ve thought about it. When I think about it I feel people see DMT entities as extraterrestrial intelligences. McK- like I’m on my own. The Logos doesn’t want to help here, and enna himself sometimes seemed to lean toward this conclu- has nothing to say to me on the subject of biological death. sion, so it might then come as a surprise to hear him muse What I imagine happens is that for the self time begins to later in the same talk: “I think in service of parsimony... these flow backwards; even before death, the act of dying is the act [entities] must be human souls.” This statement raises some of reliving an entire life, and at the end of the dying process, beautiful and eerie prospects. -

Ibogaine & the Drugs of Religion

TRUTH SEEKER TRUTH SEEKER Est. 1873 Vol.117, No.5 P.O.Box2832 San Diego, California 92112 619-239-9043 Focus Nature of Addictive Disorders Addiction: Nature vs Nurture—Again? James W. Prescott Nature of Addiction Stanton Peele Biological Balance and Addictions Ray Peat Tabernanthe Ibogaine Ibogaine: An Open Letter Howard Lotsof Ibogaine: Miracle Cure? Max Cantor. Interviews: Ibogaine Treated Addicts Max Cantor ICASH: International Coalition For Addict Self Help Bob Rand Tabernanthe Iboga: An African Plant Of Social Importance Harrison G. Pope, Jr Tabernanthe Iboga: Narcotic Ecstasis and The Work Of The Ancestors James W. Fernandez Drugs, Religion and The Healing Process James W. Prescott Marijuana Medical Marijuana R. C. Randall The Many Uses of Hemp Chris Conrad Why Not Use Hemp To Reverse The Greenhouse Effect & Save The World Jack Herer The Environmental Impact Of The Laws Against Marijuana Alan W. Bock 51 Drug Treatment Perspectives Executive Summary: Commentary On 20th Annual Report. Research Advisory Panel For The California Governor & Legislature Frederick H. Meyers 53 Save Our Selves: A Revolution in Recovery James Christopher 54 Humanistic Recovery Programs Felix R. Bremy 58 Forum What Religious Freedom Means Edd Doerr .... 62 Atheism: A Path to Social Justice Melvin Kornbluth .... 63 Superior Men .James Hervey Johnson .... 64 Art Credits Cover depicts the root and leaf of the African Ibogaine plant, a major focus of this issue. Cover Illustration: silhouette photo by Marti Kranzberg Computer-enhanced photo and Ibogaine illustration by John Carlson The Truth Seeker Vol. 117 • No.5 Fall 1990 Page 1 Addiction: Nature vs. Nurture — Again? by James W. -

Visions on Iboga/Ine from the International Community

VISIONS ON IBOGA/INE FROM THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY Iboga Community Engagement Initiative PHASE I REPORT December 2019 A project by: International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research and Service (ICEERS) Project leads Ricard Faura, PhD Andrea Langlois Advisory Committee Benjamin De Loenen, Dr. Tom Kingsley Brown, Doug Greene, Patrick Kroupa, Jeremy Weate, Hattie Wells, and Sarita Wilkins Scientific, legal and technical advice Dr. Kenneth Alper, Dr. José Carlos Bouso, Christine Fitzsimmons, Yann Guignon, Dr. Uwe Maas, Dr. Dennis McKenna, Tanea Paterson, Genís Ona, Natalia Rebollo, Dr. Constanza Sánchez, Süster Strubelt, and Clare Wilkins Editing Sarita Wilkins, Eric Swenson, Holly Weese Graphic design Àlex Verdaguer December 2019 For further information or inquiries, please email: [email protected] www.iceers.org Thank you…. As with any intitiative, this project has come to fruition thanks to the generosity of many collaborators, interviewees and survey participants. Hundreds of individuals shared knowledge, opinions, concerns, time, and visions for a future where iboga and ibogaine are valued and integrated into the global society and the rights of people connected to these practices are protected. We extend a heartfelt thank you to each and every one of them, for this report would not have been possible without their contributions. Our hope is that this report be received as the weaving of knowledge that it is, as a collection of perspectives, to be engaged with, challenged, expanded upon, and leveraged to build a brighter future. Dedication… This report is dedicated to Doug Greene. Although he is no longer with us, his gentle, persistent dedication to the healing of humanity will continue to inspire. -

“Stoned Ape Theory” on the Origins of Consciousness and Language: Implications for Language Pedagogy

Journal of Conscious Evolution Volume 16 Issue 1 Articles from an Art and Consciousness Article 6 Class 11-7-2020 An Exploration of Linguistic Relativity Theory for Consideration of Terence McKenna’s “Stoned Ape Theory” on the Origins of Consciousness and Language: Implications for Language Pedagogy Nicole Lopez California Institute of Integral Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Cognition and Perception Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, Social Psychology Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Lopez, Nicole (2020) "An Exploration of Linguistic Relativity Theory for Consideration of Terence McKenna’s “Stoned Ape Theory” on the Origins of Consciousness and Language: Implications for Language Pedagogy," Journal of Conscious Evolution: Vol. 16 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal/vol16/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conscious Evolution by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, -

Managed Madness Gabriel Roberts [email protected]

University of Washington Tacoma UW Tacoma Digital Commons MAIS Projects and Theses School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Spring 2019 Managed Madness Gabriel Roberts [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/ias_masters Part of the Other Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Gabriel, "Managed Madness" (2019). MAIS Projects and Theses. 59. https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/ias_masters/59 This Open Access (no embargo, no restriction) is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at UW Tacoma Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAIS Projects and Theses by an authorized administrator of UW Tacoma Digital Commons. Running head: MANAGED MADNESS 1 Managed Madness: Foucault & McKenna’s Use of Madness and The Psychedelic Experience As A Tool of Critique Gabriel D. Roberts A proposal submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master's Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies Gabriel D. Roberts Proposed Supervisor Dr. Asao Inoue - (MAIS) Proposed Reader(s) Dr. Ingrid Walker - (IAS) MANAGED MADNESS 2 Table of contents Author’s note…………………………………………………………………………....3 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………...8 Chapter 1: A philosopher’s new set of eyes…………………………………………....14 Chapter 2: Foucault’s perspective on Madness………………………………………...18 Chapter 3: Terence McKenna & The Psychedelic Lens……………………………......28 Chapter 4: Interviews…………………………………………………………………...39 Chapter 5: Final Thoughts……………………………………………………………...52 References……………………………………………………………………………...60 MANAGED MADNESS 3 Author Note Special thanks are in order to Dr. Asao Inoue who has shown me the power of words and how they shape the reality that we share. His insights on pedagogy, classical rhetoric and writing have enabled me to greatly expand my own knowledge and skill.