Timothy Leary's Legacy and the Rebirth of Psychedelic Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Being Healed: an Ethnography of Ayahuasca and the Self at the Temple of the Way of Light, Iquitos, Peru

Being Healed: An Ethnography of Ayahuasca and the Self at the Temple of the Way of Light, Iquitos, Peru DENA SHARROCK BSocSci (Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology and Anthropology) School of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Newcastle December 2017 This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I hereby certify that the work embodied in the thesis is my own work, conducted under normal supervision. The thesis contains no material which has been accepted, or is being examined, for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University’s Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 and any approved embargo. Signed: Date: 23rd December 2017 i ABSTRACT This thesis explores the experiences, articulations and meaning-making of a group of people referred to as pasajeros: middle class Westerners and people living in Western-style cultures from around the globe, who travel to the Temple of the Way of Light (‘the Temple’) in the Peruvian Amazon, to explore consciousness and seek healing through ceremonies with Shipibo ‘shamans’ and the plant medicine, ayahuasca. In the thesis, I explore the health belief systems of pasajeros, examining the syncretic space of the Temple in which Western and Eastern, New Age, biomedical, and shamanic discourses meet and intertwine to create novel sets of health beliefs, practices, and perceptions of the Self. -

Hallucinogens - LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP

Hallucinogens - LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP Hallucinogenic compounds found in some • Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N- plants and mushrooms (or their extracts) dimethyltryptamine) is obtained from have been used—mostly during religious certain types of mushrooms that are rituals—for centuries. Almost all indigenous to tropical and subtropical hallucinogens contain nitrogen and are regions of South America, Mexico, and classified as alkaloids. Many hallucinogens the United States. These mushrooms have chemical structures similar to those of typically contain less than 0.5 percent natural neurotransmitters (e.g., psilocybin plus trace amounts of acetylcholine-, serotonin-, or catecholamine- psilocin, another hallucinogenic like). While the exact mechanisms by which substance. hallucinogens exert their effects remain • PCP (phencyclidine) was developed in unclear, research suggests that these drugs the 1950s as an intravenous anesthetic. work, at least partially, by temporarily Its use has since been discontinued due interfering with neurotransmitter action or to serious adverse effects. by binding to their receptor sites. This DrugFacts will discuss four common types of How Are Hallucinogens Abused? hallucinogens: The very same characteristics that led to • LSD (d-lysergic acid diethylamide) is the incorporation of hallucinogens into one of the most potent mood-changing ritualistic or spiritual traditions have also chemicals. It was discovered in 1938 led to their propagation as drugs of abuse. and is manufactured from lysergic acid, Importantly, and unlike most other drugs, which is found in ergot, a fungus that the effects of hallucinogens are highly grows on rye and other grains. variable and unreliable, producing different • Peyote is a small, spineless cactus in effects in different people at different times. -

Hallucinogens - LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP

Information for Behavioral Health Providers in Primary Care Hallucinogens - LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP What are Hallucinogens? Hallucinogenic compounds found in some plants and mushrooms (or their extracts) have been used— mostly during religious rituals—for centuries. Almost all hallucinogens contain nitrogen and are classified as alkaloids. Many hallucinogens have chemical structures similar to those of natural neurotransmitters (e.g., acetylcholine-, serotonin-, or catecholamine-like). While the exact mechanisms by which hallucinogens exert their effects remain unclear, research suggests that these drugs work, at least partially, by temporarily interfering with neurotransmitter action or by binding to their receptor sites. This InfoFacts will discuss four common types of hallucinogens: LSD (d-lysergic acid diethylamide) is one of the most potent mood-changing chemicals. It was discovered in 1938 and is manufactured from lysergic acid, which is found in ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and other grains. Peyote is a small, spineless cactus in which the principal active ingredient is mescaline. This plant has been used by natives in northern Mexico and the southwestern United States as a part of religious ceremonies. Mescaline can also be produced through chemical synthesis. Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine) is obtained from certain types of mushrooms that are indigenous to tropical and subtropical regions of South America, Mexico, and the United States. These mushrooms typically contain less than 0.5 percent psilocybin plus trace amounts of psilocin, another hallucinogenic substance. PCP (phencyclidine) was developed in the 1950s as an intravenous anesthetic. Its use has since been discontinued due to serious adverse effects. How Are Hallucinogens Abused? The very same characteristics that led to the incorporation of hallucinogens into ritualistic or spiritual traditions have also led to their propagation as drugs of abuse. -

From Sacred Plants to Psychotherapy

From Sacred Plants to Psychotherapy: The History and Re-Emergence of Psychedelics in Medicine By Dr. Ben Sessa ‘The rejection of any source of evidence is always treason to that ultimate rationalism which urges forward science and philosophy alike’ - Alfred North Whitehead Introduction: What exactly is it that fascinates people about the psychedelic drugs? And how can we best define them? 1. Most psychiatrists will define psychedelics as those drugs that cause an acute confusional state. They bring about profound alterations in consciousness and may induce perceptual distortions as part of an organic psychosis. 2. Another definition for these substances may come from the cross-cultural dimension. In this context psychedelic drugs may be recognised as ceremonial religious tools, used by some non-Western cultures in order to communicate with the spiritual world. 3. For many lay people the psychedelic drugs are little more than illegal and dangerous drugs of abuse – addictive compounds, not to be distinguished from cocaine and heroin, which are only understood to be destructive - the cause of an individual, if not society’s, destruction. 4. But two final definitions for psychedelic drugs – and those that I would like the reader to have considered by the end of this article – is that the class of drugs defined as psychedelic, can be: a) Useful and safe medical treatments. Tools that as adjuncts to psychotherapy can be used to alleviate the symptoms and course of many mental illnesses, and 1 b) Vital research tools with which to better our understanding of the brain and the nature of consciousness. Classifying psychedelic drugs: 1,2 The drugs that are often described as the ‘classical’ psychedelics include LSD-25 (Lysergic Diethylamide), Mescaline (3,4,5- trimethoxyphenylathylamine), Psilocybin (4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine) and DMT (dimethyltryptamine). -

Psychedelics and Entheogens: Implications of Administration in Medical and Non- Medical Contexts

Psychedelics and Entheogens: Implications of Administration in Medical and Non- Medical Contexts by Hannah Rae Kirk A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Biology (Honors Scholar) Presented May 23, 2018 Commencement June 2018 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Hannah Rae Kirk for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Biology presented on May 23, 2018. Title: Psychedelics and Entheogens: Implications of Administration in Medical and Non-Medical Contexts. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Robin Pappas Psychedelics and entheogens began as religious sacraments. They were apotheosized for their mind-expanding powers and were thought to open realms to the world of the Gods. It was not until the first psychedelic compound was discovered in a laboratory setting a mere hundred years ago that they entered into formal scientific study. Although they were initially well-received in academic and professional circles, research into their potential was interrupted when they were made illegal. Only recently have scientists renewed the investigation of psychedelic substances, in the hope of demonstrating their potential in understanding and healing the human mind. This thesis will explore the history of psychedelics and entheogens, consider the causes behind the prohibition of their research, and outline their reintroduction into current scientific research. Psychedelic compounds have proven to be magnifiers of the mind and, under appropriate circumstances, can act as medicaments in both therapeutic and non-medical contexts. By exploring the journey of psychedelic substances from sacraments, to therapeutic aids, to dangerous drugs, and back again, this thesis will highlight what is at stake when politics and misinformation suppresses scientific research. -

Recollections of the Good Friday Experiment - Interview with Huston Smith

Recollections of the Good Friday Experiment - Interview with Huston Smith by Huston Smith Interviewed by Thomas B. Roberts Dekalb, Illinois and Robert N. Jesse San Francisco, California original source: http://www.atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-29-97-02-099.pdf backup source: http://www.psilosophy.info/resources/trps-29-97-02-099.pdf T.B.R.: This is October 1, 1996. Huston Smith will be telling us about an event that happened in the Good Friday Experiment in 1962. Huston, do you want to tell us about the student who ran out of the experiment? Huston Smith: The basic facts of the experiment have been recorded elsewhere and are fairly well known, but I will summarize them briefly. In the early sixties, Walter Pahnke, an M.D. with strong interests in mysticism, wanted to augment his medical knowledge with a doctorate from the Harvard Divinity School (Pahnke, 1963). He had heard that the psychedelics often occasion mystical experiences, so he decided to make that issue the subject of his doctoral research. He obtained the support of Howard Thurman, Dean of Marsh Chapel at Boston University, for his project and also that of Walter Houston Clark who taught psychology of religion at Andover Newton Theological Seminary and shared Wally's [Pahnke] interest in the psychedelics. Clark procured volunteers from his seminary to engage in an experiment. Howard Thurman's three-hour 1962 Good Friday service at Boston University would be piped down to a small chapel in the basement of the building where the volunteers, augmented by Walter Clark and myself, would participate in it. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Religious Implications of Psychedelics

Religious Implications Wliarevcr rlie co~iclusion,rl~e debare ant1 rhe ~rsysl~edeliccxl)losion which ser it off, rurncd arrcnrion ro ~lleilrrriglring relarior~sliil)hcrween Psyche, Soul, and Spirit drugs and religion. Ir soon became apparenr rllar rl~ereligious uscofdrllgs to induce sacred stares of consciousness has been widesllread across nunierolrs culrures. Hisrorical examples inclt~de[he fivkco~rof 111s Greek Eleusinian nlysrcries, [he Ausrraliali al)origiries' pirirri, Hinrl~lisnisso,ir,~, Tlbrrc is a conrintlum oicosmic cnnwiousncss against which our ilidi- rhc wine ofDionysis Elcu~lrerios(Diolrysis rlie liberalor), and rlie Zoroas- viduality builds bur accidcn~aliurces and into which our wcral minds rrians' honina.4 Conrenlporary exarnplcs also abutlnd, sucli as rlie use of ylungc 3s into a nn~thersca. -William James1 marijuana hy Rastafarians alrJ some InJian yogis, Narivc American peyote, and rhe Sourh American shaniaris' ayalluasca.1 Nornarrer wliar rl~e currenr debare in rhe Wesr, ir seems clear ihar for cel~n~riesorller cl~lrl~res Psychedelics cerrainly srarrled and shook rhe \\'esrcrn world. Bur one of have agreed rliar psychedelics are capable of produci~~gvaluable religious the grearesr surprises was rhar psychedelics prnduccd religious experiences. experiences. A significanr number of people, including sraunch arheisrs and Marxisrs, claimed ro have found korsho in a capsule, mokslm in amushroom, or U~isuspccringWesterners who experi~~ie~itrdwirli rliese drugs were nor immune to rheir religious and spirirual impacr, and rhis inipacr rook rdtor; in a psychedelic. In hcr, rhcse claims proved so consisrenr over so rhree forms. The firsr was 3 spirirual iniriarion. Many people llad rheir firsr 111any years [hat some researchers have renamed psychedelics signilicar~~religious-spirirual exl~ericnceon psychedelics. -

“Wellness Cruises” with Dr. Andrew Weil, Bound for Arabia in 2019 and Australia/New Zealand in 2020

Seabourn Announces “Wellness Cruises” with Dr. Andrew Weil, Bound for Arabia in 2019 and Australia/New Zealand in 2020 March 7, 2019 SEATTLE, March 7, 2019 – Based on the success of its 2018 Wellness Voyages Seabourn, the world's finest ultra- luxury travel experience, is setting its sights on mindful, healthy living in the year ahead by announcing two content rich Wellness Cruises bound for Arabia and the South Pacific. Inspired by the rising interest in wellness that is transforming travel and lifestyles around the globe, each wellness cruise is being fashioned with input from celebrated physician, best-selling author and Seabourn partner Dr. Andrew Weil, whose exclusive mindful living program, Spa & Wellness with Dr. Andrew Weil is a popular offering on every vessel and every voyage in the Seabourn fleet. With renowned Seabourn service, diverse itineraries and culturally rich destinations as a backdrop, the Wellness Cruises will be highly informative, enjoyable, and unforgettable. These specific itineraries will include lectures, discussions, classes, and demonstrations led by Dr. Weil and an additional four experts in Integrative Medicine and packed with information on how guests can enrich their lives for better mental and physical health. "Wellness is a growing phenomenon – and rightly so – as people around the world seek to live better, healthier, and more mindfully for the benefit of their overall wellbeing," noted Richard Meadows, president of Seabourn. "We have had great success with Spa & Wellness with Dr. Andrew Weil on Seabourn voyages around the world, and we're excited to follow up our past two wellness cruises with these new opportunities to learn from a group of highly regarded experts." The Ancient Path to Wellness The next Seabourn Wellness Cruise will launch with Route to Ancient Wellness aboard Seabourn Ovation, scheduled November 13-December 2, 2019. -

ELCOCK-DISSERTATION.Pdf

HIGH NEW YORK THE BIRTH OF A PSYCHEDELIC SUBCULTURE IN THE AMERICAN CITY A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By CHRIS ELCOCK Copyright Chris Elcock, October, 2015. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History Room 522, Arts Building 9 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Canada i ABSTRACT The consumption of LSD and similar psychedelic drugs in New York City led to a great deal of cultural innovations that formed a unique psychedelic subculture from the early 1960s onwards. -

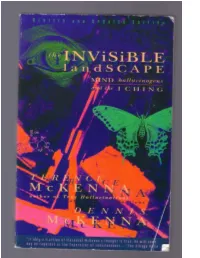

THE INVISIBLE LANDSCAPE: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching

To inquire about Time Wave software in both Macintosh and DOS versions please contact Blue Water Publishing at 1-800-366-0264. fax# (503) 538-8485. or write: P.O. Box 726 Newberg, OR 97132 Passage from The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, edited by David V. Erdman. Commentary by Harold Bloom. Copyright © 1965 by David V. Erdman and Harold Bloom. Published by Doubleday Company, Inc. Used by permission. THE INVISIBLE LANDSCAPE: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching. Copyright © 1975, 1993 by Dennis J. McKenna and Terence K. McKenna. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022. Interior design by Margery Cantor and Jaime Robles FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1975 BY THE SEABURY PRESS FIRST HARPERCOLLINS EDITION PUBLISHED IN 1993 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McKenna, Terence K., 1946- The Invisible landscape : mind, hallucinogens, and the I ching / Terence McKenna and Dennis McKenna.—1st HarperCollins ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-06-250635-8 (acid-free paper) 1. I ching. 2. Mind and body. 3. Shamanism. I. Oeric, O. N. II. Title. BF161.M47 1994 133—dc2o 93-5195 CIP 01 02 03 04 05 RRD(H) 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 In Memory of our dear Mother Thus were the stars of heaven created like a golden chain To bind the Body of Man to heaven from falling into the Abyss. -

Strategic Leadership Workshop

Strategic Leadership Workshop The MindBodySpirit Process: How to Coach Yourself and Others Towards Positive Behavioral Change October 17, 2009 9:00 AM – noon, Room 121 Abessinio Bldg Workshop Leaders: Dr. Jeff Kaplan and Dr. Robert Bulgarelli Neumann University’s Strategic Leadership Program , in partnership with The Habit Change Company , will sponsor a free workshop for current students and alumni. The Habit Change Company helps students, managers, executives, hospital patients, and others do something very hard …choose and sustain healthy behaviors over unhealthy behaviors. This 3-hour experiential workshop taps into key processes taken from a proprietary 15-month habit change process. Delivered by two of The Habit Change Company’s founders, this program is designed to help you increase your performance and your health. During this program you will take a deep and honest look at your habits in the areas of work, time management, sleep, stress management, nutrition and exercise. At the completion of the program, you will have taken the first steps towards mapping out a life plan that supports your professional and personal goals. The objectives of this 3-hour experiential workshop are: Learn and practice a technique to reduce stress immediately while increasing self- awareness Understand the reason people struggle with habit change and the 5 barriers that surface when attempting change Learn and use a tool to help you and your clients assess their current habits across 8 life practices Begin to understand the psychological and medical underpinnings around habit change Develop a vision for professional and personal success and begin to map out steps to help achieve this vision The MindBodySpirit (MBS) Process, developed by The Habit Change Company, is a new approach to health and wellness, helping individuals take better control of their health, gain greater vitality, and live longer lives.