Legal Issues of Multinational Military Units Tasks and Missions, Stationing Law, Command and Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New NATO Headquarters

North Atlantic Treaty Organization www.nato.int/factsheets Factsheet February 2018 New NATO Headquarters NATO is moving to a new headquarters - a home for our modern and adaptable Alliance. Designed to resemble interlocking fingers, the new headquarters symbolizes NATO’s unity and cooperation. The new building will accommodate NATO’s changing needs long into the future. NATO has been based in its current facility since 1967. Since then, the number of NATO members has almost doubled – from 15 to 29 – and many partners have opened diplomatic offices at NATO. As a result, almost one-fifth of our office space is now located in temporary structures. With more than 254,000 square meters of space, the new HQ will accommodate: • 1500 personnel from Allied delegations; • 1700 international military and civilian staff; • 800 staff from NATO agencies; • Frequent visitors, which currently number some 500 per day. The state-of-the-art design of the building will also allow for further expansion if needed. A green building The new headquarters has been designed and built with the environment in mind. It will reduce energy use thanks to extensive thermal insulation, solar-glazing protection and advanced lighting systems. The windows covering the building allow it to take maximum advantage of natural light, reducing consumption of electricity. State-of-the-art “cogeneration” units will provide most of the electricity and heating used on site. A geo-thermal heating and cooling system will use the constant temperature beneath the surface of the ground to provide heat during the winter and to cool the building in summer. -

Militärgerichtsbarkeit in Österreich (Circa 1850–1945)

BRGÖ 2016 Beiträge zur Rechtsgeschichte Österreichs Martin MOLL, Graz Militärgerichtsbarkeit in Österreich (circa 1850–1945) Military jurisdiction in Austria, ca. 1850–1945 This article starts around 1850, a period which saw a new codification of civil and military penal law with a more precise separation of these areas. Crimes committed by soldiers were now defined parallel to civilian ones. However, soldiers were still tried before military courts. The military penal code comprised genuine military crimes like deser- tion and mutiny. Up to 1912 the procedure law had been archaic as it did not distinguish between the state prosecu- tor and the judge. But in 1912 the legislature passed a modern military procedure law which came into practice only weeks before the outbreak of World War I, during which millions of trials took place, conducted against civilians as well as soldiers. This article outlines the structure of military courts in Austria-Hungary, ranging from courts responsible for a single garrison up to the Highest Military Court in Vienna. When Austria became a republic in November 1918, military jurisdiction was abolished. The authoritarian government of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß reintroduced martial law in late 1933; it was mainly used against Social Democrats who staged the February 1934 uprising. After the National Socialist ‘July putsch’ of 1934 a military court punished the rioters. Following Aus- tria’s annexation to Germany in 1938, German military law was introduced in Austria. After the war’s end in 1945, these Nazi remnants were abolished, leaving Austria without any military jurisdiction. Keywords: Austria – Austria as part of Hitler’s Germany –First Republic – Habsburg Monarchy – Military Jurisdiction Einleitung und Themenübersicht allen Staaten gab es eine eigene, von der zivilen Justiz getrennte Strafgerichtsbarkeit des Militärs. -

The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs

Jeremy Stöhs ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Jeremy Stöhs is the Deputy Director of the Austrian Center for Intelligence, Propaganda and Security Studies (ACIPSS) and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Institute for Security Policy, HOW HIGH? Kiel University. His research focuses on U.S. and European defence policy, maritime strategy and security, as well as public THE FUTURE OF security and safety. EUROPEAN NAVAL POWER AND THE HIGH-END CHALLENGE ISBN 978875745035-4 DJØF PUBLISHING IN COOPERATION WITH 9 788757 450354 CENTRE FOR MILITARY STUDIES How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Djøf Publishing In cooperation with Centre for Military Studies 2021 Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge © 2021 by Djøf Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior written permission of the Publisher. This publication is peer reviewed according to the standards set by the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science. Cover: Morten Lehmkuhl Print: Ecograf Printed in Denmark 2021 ISBN 978-87-574-5035-4 Djøf Publishing Gothersgade 137 1123 København K Telefon: 39 13 55 00 e-mail: [email protected] www. djoef-forlag.dk Editors’ preface The publications of this series present new research on defence and se- curity policy of relevance to Danish and international decision-makers. -

NATO, the Baltic States, and Russia a Framework for Enlargement

NATO, the Baltic States, and Russia A Framework for Enlargement Mark Kramer Harvard University February 2002 In 2002, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) will be initiating its second round of enlargement since the end of the Cold War. In the late 1990s, three Central European countries—Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland—were admitted into the alliance. At a summit due to be held in Prague in November 2002, the NATO heads-of-state will likely invite at least two and possibly as many as six or seven additional countries to join. In total, nine former Communist countries have applied for membership. Six of the prospective new members—Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania, Albania, and Macedonia—lie outside the former Soviet Union. Of these, only Slovakia and Slovenia are likely to receive invitations. The three other aspiring members of NATO—Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia— normally would stand a good chance of being admitted, but their status has been controversial because they were republics of the Soviet Union until August 1991. Until recently, the Russian government had vehemently objected to the proposed admission of the Baltic states into NATO, and many Western leaders were reluctant to antagonize Moscow. During the past year-and-a-half, however, the extension of NATO membership to the Baltic states in 2002 has become far more plausible. The various parties involved—NATO, the Baltic states, and Russia—have modified their policies in small but significant ways. Progress in forging a new security arrangement in Europe began before the September 2001 terrorist attacks, but the improved climate of U.S.-Russian relations since the attacks has clearly expedited matters. -

Internship Programme GUIDE for NEWCOMERS

Internship Programme GUIDE FOR NEWCOMERS Internship Programme GUIDE FOR NEWCOMERS 2017 Internship Programme GUIDE FOR NEWCOMERS 4 Internship Programme GUIDE FOR NEWCOMERS TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Note from the Secretary General ............................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 1. ABOUT THE INTERNSHIP PROGRAMME ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 A. Background ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 11 B. General Conditions ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 12 C. Proceduress ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Newsletter for the Baltics Week 47 2017

Royal Danish Embassy T. Kosciuskos 36, LT-01100 Vilnius Tel: +370 (5) 264 8768 Mob: +370 6995 7760 The Defence Attaché To Fax: +370 (5) 231 2300 Estonia, Latvia & Lithuania Newsletter for the Baltics Week 47 2017 The following information is gathered from usually reliable and open sources, mainly from the Baltic News Service (BNS), respective defence ministries press releases and websites as well as various newspapers, etc. Table of contents THE BALTICS ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Baltic States discuss how to contribute to fight against jihadists ............................................... 3 THE BALTICS AND RUSSIA .................................................................................................................. 3 Russian aircraft crossed into Estonian airspace ............................................................................ 3 NATO military aircraft last week scrambled 3 times over Russian military aircraft .................... 3 Belgian aircraft to conduct low-altitude flights in Estonian airspace .......................................... 3 Three Russian military aircraft spotted near Latvian borders ...................................................... 4 THE BALTICS AND EXERCISE .............................................................................................................. 4 Estonia’s 2nd Infantry Brigade takes part in NATO’s Arcade Fusion exercise ........................... -

The Rise and Fall of an Internationally Codified Denial of the Defense of Superior Orders

xv The Rise and Fall of an Internationally Codified Denial of the Defense of Superior Orders 30 Revue De Droit Militaire Et De Droit De LA Guerre 183 (1991) Introduction s long as there have been trials for violations of the laws and customs of A war, more popularly known as "war crimes trials", the trial tribunals have been confronted with the defense of "superior orders"-the claim that the accused did what he did because he was ordered to do so by a superior officer (or by his Government) and that his refusal to obey the order would have brought dire consequences upon him. And as along as there have been trials for violations of the laws and customs ofwar the trial tribunals have almost uniformly rejected that defense. However, since the termination of the major programs of war crimes trials conducted after World War II there has been an ongoing dispute as to whether a plea of superior orders should be allowed, or disallowed, and, if allowed, the criteria to be used as the basis for its application. Does international action in this area constitute an invasion of the national jurisdiction? Should the doctrine apply to all war crimes or only to certain specifically named crimes? Should the illegality of the order received be such that any "reasonable" person would recognize its invalidity; or should it be such as to be recognized by a person of"ordinary sense and understanding"; or by a person ofthe "commonest understanding"? Should it be "illegal on its face"; or "manifesdy illegal"; or "palpably illegal"; or of "obvious criminality,,?1 An inability to reach a generally acceptable consensus on these problems has resulted in the repeated rejection of attempts to legislate internationally in this area. -

Request for Information Rfi-Act-Sact-21-56 Amendment 1 (Additions Are in Red)

HQ Supreme Allied Command Transformation RFI-ACT-SACT-21-56 Headquarters Supreme Allied Commander Transformation Norfolk Virginia REQUEST FOR INFORMATION RFI-ACT-SACT-21-56 AMENDMENT 1 (ADDITIONS ARE IN RED) This document contains a Request for Information (RFI) Call for Industry participation in NATO Crisis Management Exercise 2022 (CMX-22). Suppliers wishing to respond to this RFI should read this document carefully and follow the guidance for responding. Page 1 of 8 HQ Supreme Allied Command Transformation RFI-ACT-SACT-21-56 Call for Industry Demonstration during NATO Crisis Management Exercise 2022 (CMX22) HQ Supreme Allied Commander Transformation RFI 21-56 General Information Request For Information No. 21-56 Project Title Request for industry input to NATO Crisis Management Exercise 2022 Due date for submission of requested 2 June 2021 information Contracting Office Address NATO, HQ Supreme Allied Commander Transformation (SACT) Purchasing & Contracting Suite 100 7857 Blandy Rd, Norfolk, VA, 23511- 2490 Contracting Points of Contact 1. Ms Tonya Bonilla e-mail : [email protected] Tel : +1 757 747 3575 2. Ms Catherine Giglio e-mail : [email protected] Tel :+1 757 747 3856 Technical Points of Contact 1. Angel Martin, e-mail : [email protected] Tel : +1 757 747 4322 2. Jan Hodicky, e-mail : [email protected] Tel : +1 757 747 4118 ALL EMAIL CORRESPONDENCE MUST INCLUDE BOTH CONTRACTING AND TECHNICAL POCS LISTED ABOVE INTRODUCTION 1. Summary. HQ Supreme Allied Commander Transformation (HQ SACT) is issuing this Request For Information (RFI) announcement to explore existing technologies, which can be used to assist in political and military strategic decision- making and to determine the level of interest within industry for showcasing technology demonstrations during NATO Crisis Management Exercise 2022 (CMX22) in March 2022. -

Európai Tükör Xv

EURÓ PA I TÜ KÖR A KÜLÜGYMINISZTÉRIUM FOLYÓIRATA 2010. MÁJUS A TARTALOMBÓL Berend T. Iván: Válságtól válságig: új európai Zeitgeist az ezredfordulón (1973–2008) Járóka Lívia: Egy európai roma stratégia lehetõsége és szükséges- sége Makkay Lilla: A balti-tengeri térség és az EU balti- EURÓPAI TÜKÖR XV. ÉVF. 5. SZÁM tengeri stratégiája Kátai Anikó: Az Európai Unió követ- kezõ tíz évre szóló versenyképességi és foglalkoztatási stra- tégiája – az Európa 2020 stratégia Siposné Kecskeméthy Klára: A mediterrán térség és az Európai Unió XV. ÉVFOLYAM 5. SZÁM 2010. MÁJUS EURÓPAI TÜKÖR Kiadja a Magyar Köztársaság Külügyminisztériuma, a HM Zrínyi Kommunikációs Szolgáltató Kht. támogatásával. Felelõs kiadó: Tóth Tamás A szerkesztõbizottság elnöke: Palánkai Tibor A szerkesztõbizottság tagjai: Bagó Eszter, Balázs Péter, Balogh András, Barabás Miklós, Baráth Etele, Bod Péter Ákos, Erdei Tamás, Gottfried Péter, Halm Tamás, Hefter József, Horváth Gyula, Hörcsik Richárd, Inotai András, Iván Gábor, Kádár Béla, Kassai Róbert, Kazatsay Zoltán, Levendel Ádám, Lõrincz Lajos, Magyar Ferenc, Nyers Rezsõ, Somogyvári István, Szekeres Imre, Szent-Iványi István, Török Ádám, Vajda László, Vargha Ágnes Fõszerkesztõ: Forgács Imre Lapszerkesztõ: Hovanyecz László Lapigazgató: Bulyovszky Csilla Rovatszerkesztõk: Fazekas Judit, Becsky Róbert Szerkesztõk: Asztalos Zsófia, Farkas József György Mûszaki szerkesztõ: Lányi György A szerkesztõség címe: Magyar Köztársaság Külügyminisztériuma 1027 Budapest, Nagy Imre tér 4. Telefon: 458-1475, 458-1577, 458-1361 Terjesztés: Horváthné Stramszky Márta, [email protected] Az Európai Integrációs Iroda kiadványai hozzáférhetõk az Országgyûlési Könyvtárban, valamint a Külügyminisztérium honlapján (www.kulugyminiszterium.hu; Kiadványaink menüpont). A kiadványcsalád borítón látható emblémája Szutor Zsolt alkotása. Nyomdai elõkészítés: Platina Egyéni Cég Nyomdai kivitelezés: Pharma Press Kft. ISSN 1416-6151 EURÓPAI TÜKÖR 2010/5. -

The Development of Regular Army Officers – an Essay

Baltic Defence Review No. 3 Volume 2000 The development of regular army officers an essay By Michael H. Clemmesen, Brigadier General, MA (history) One must understand the mechanism and the power of the individual soldier,,, model is expensive in manpower cost (in then that of a company, a battalion, a brigade and so on, before one can ven- a Western industrialised state), relative ture to group divisions and move an army. I believe I owe most of my success to cheap in training cost due to the long the attention I always paid to the inferior part of tactics as a regimental officer... service contracts, and relatively cheap in There are few men in the Army who knew these details better than I did; it is equipment as a result of the limited size. the foundation of all military knowledge. The Duke of Wellington. The training-mobilisation army is relevant The standing force army is likely to be in continental states faced with a poten- Two army models attractive to states without any massive, tial (rather than an immediate) massive direct, overland threat to their territory. scale overland treat that makes it neces- It will often help and clarify an analy- In the pure version of that army, the sol- sary to have a large section of the state sis to establish the theoretical, pure mod- diers will have long service contracts. Be- population available for direct defence. els that can be used as references. In this cause of its potential high readiness, in- The potentially large trained manpower essay I shall use the two basic types of cluding mature unit cohesion, this army pool makes it possible to mobilise an army armies that influence the land forces of model is useful for external intervention that can defend the borders and territory the real world: the standing force army operations and in support of the police in depth. -

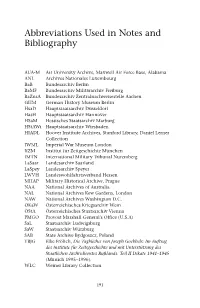

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Nato Enlargement: Qualifications and Contributions—Parts I–Iv Hearings

S. HRG. 108–180 NATO ENLARGEMENT: QUALIFICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTIONS—PARTS I–IV HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 27, AND APRIL 1, 3 AND 8, 2003 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 90–325 PDF WASHINGTON : 2003 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 17:42 Nov 12, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 90325 SFORELA1 PsN: SFORELA1 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana, Chairman CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware LINCOLN CHAFEE, Rhode Island PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland GEORGE ALLEN, Virginia CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio BARBARA BOXER, California LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee BILL NELSON, Florida NORM COLEMAN, Minnesota JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire JON S. CORZINE, New Jersey KENNETH A. MYERS, JR., Staff Director ANTONY J. BLINKEN, Democratic Staff Director (II) VerDate 11-MAY-2000 17:42 Nov 12, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 90325 SFORELA1 PsN: SFORELA1 CONTENTS Thursday, March 27, 2003—Part I Page Allen, Hon. George, U.S. Senator from Virginia, opening statement .................