Birds of Nakusp, New Denver, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francophone Historical Context Framework PDF

Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Canot du nord on the Fraser River. (www.dchp.ca); Fort Victoria c.1860. (City of Victoria); Fort St. James National Historic Site. (pc.gc.ca); Troupe de danse traditionnelle Les Cornouillers. (www. ffcb.ca) September 2019 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Table of Contents Historical Context Thematic Framework . 3 Theme 1: Early Francophone Presence in British Columbia 7 Theme 2: Francophone Communities in B.C. 14 Theme 3: Contributing to B.C.’s Economy . 21 Theme 4: Francophones and Governance in B.C. 29 Theme 5: Francophone History, Language and Community 36 Theme 6: Embracing Francophone Culture . 43 In Closing . 49 Sources . 50 2 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework - cb.com) - Simon Fraser et ses Voya ses et Fraser Simon (tourisme geurs. Historical contexts: Francophone Historic Places • Identify and explain the major themes, factors and processes Historical Context Thematic Framework that have influenced the history of an area, community or Introduction culture British Columbia is home to the fourth largest Francophone community • Provide a framework to in Canada, with approximately 70,000 Francophones with French as investigate and identify historic their first language. This includes places of origin such as France, places Québec, many African countries, Belgium, Switzerland, and many others, along with 300,000 Francophiles for whom French is not their 1 first language. The Francophone community of B.C. is culturally diverse and is more or less evenly spread across the province. Both Francophone and French immersion school programs are extremely popular, yet another indicator of the vitality of the language and culture on the Canadian 2 West Coast. -

Participating Schools 2019-2020

Participating Schools 2019-2020 SD 5 - Southeast Kootenay Amy Woodland Elementary Kootenay Orchards Elementary Ecole T M Roberts School Laurie Middle School Elkford Elementary Secondary Mount Baker Secondary Fernie Secondary Parkland Middle School Frank J Mitchell Elementary Pinewood Elementary (Cranbrook) Gordon Terrace Elementary Rocky Mountain Elementary Highlands Elementary (Cranbrook) Secondary School Isabella Dicken Elementary Sparwood Secondary Jaffray Elementary Junior Steeples Elementary Kootenay Educational Services SD 6 - Rocky Mountain Alexander Park Elementary Golden Alternate/Golden David Thompson Secondary Secondary (Invermere) Golden Secondary Edgewater Elementary J Alfred Laird Elementary Eileen Madson Primary Lady Grey Elementary Lindsay Park Elementary Martin Morigeau Elementary Open Doors Alternate Education Marysville Elementary Selkirk Secondary McKim Middle School Windermere Elementary Nicholson Elementary SD 8 - Kootenay Lake Adam Robertson Elementary Mount Sentinel Secondary Blewett Elementary School Prince Charles Brent Kennedy Elementary Secondary/Wildflower Program Canyon-Lister Elementary Redfish Elementary School Crawford Bay Elem-Secondary Rosemont Elementary Creston Homelinks/Strong Start Salmo Elementary Erickson Elementary Salmo Secondary Hume Elementary School South Nelson Elementary J V Humphries Trafalgar Middle School Elementary/Secondary W E Graham Community School Jewett Elementary Wildflower School L V Rogers Secondary Winlaw Elementary School SD 10 - Arrow Lakes Burton Elementary School Edgewood -

Brenda Mayson a Very Deserving 2004 Nakusp Citizen of the Year

April 27, 2005 The Valley Voice Volume 14, Number 8 April 27, 2005 Delivered to every home between Edgewood, Kaslo & South Slocan. Published bi-weekly. “Your independently-owned regional community newspaper serving the Arrow Lakes, Slocan & North Kootenay Lake Valleys.” Brenda Mayson a very deserving 2004 Nakusp Citizen of the Year by Jan McMurray to live, and representatives of the told her story about being Brenda’s moved back, the Dinnings also did, right wind up the evening. All four of her The celebration of Brenda various groups Brenda belongs to. neighbour twice. The first time, Dinning next door to Brenda and Harry. “It was children were there, as well as two Mayson as Nakusp’s Citizen of the Brenda said she was surprised had just moved in and Brenda was at better the second time because Harry nieces and two granddaughters. Year 2004 attracted what several and speechless when she found out the door with a lemon pie. “I was so wasn’t as noisy and the kid finally left,” Susie, Ted’s wife, said that Brenda Rotarians present said was probably she had been named Citizen of the happy to have such a thoughtful she joked. “I hope we’ll be neighbours had been a huge inspiration to her and the biggest crowd the event has ever Year. She thanked all those involved neighbour...but then there was Harry next time, up there,” she said, pointing extended congratulations. Ted said seen. The April 16 banquet and in nominating her, the Rotary Club and Ted,” she lamented jokingly, saying up to heaven. -

The Valley Voice Is a Locally-Owned Independent Newspaper

February 22, 2012 The Valley Voice 1 Volume 21, Number 4 February 22, 2012 Delivered to every home between Edgewood, Kaslo & South Slocan. Published bi-weekly. “Your independently owned regional community newspaper serving the Arrow Lakes, Slocan & North Kootenay Lake Valleys.” Ministry slaps suspension on Meadow Creek Cedar’s forest licence by Jan McMurray that the $42,000 fine and the Wiggill also explained that there rather than allowing Meadow Creek for Meadow Creek Cedar. An FPB Meadow Creek Cedar (MCC) remediation order to reforest the is one exception to the company’s Cedar to seize the logs in the bush.” spokesperson reported that the has been given notice that its forest six blocks relate directly to the licence suspension. Operations on He added that if logs are left in the investigation of that complaint is licence is suspended as of February silviculture contravention found in a cutblock in the Trout Lake area, bush too long, there is a vulnerability nearing completion. FPB complaints 29. The company was also given the recent investigation. The decision which include a road permit, will be to spruce budworm. are completely separate from ministry a $42,000 fine for failing to meet to suspend the licence, however, was allowed to continue past the February Wiggill confirmed that some investigations. its silviculture (tree planting) made based on both current and past 29 suspension date. “This is to additional ministry investigations are In addition, many violations of obligations, and an order to have contraventions. essentially protect the interests of the ongoing involving Meadow Creek safety regulations have been found the tree planting done by August 15. -

Texada Island - Sturt Bay Shipwreck Investigation a Report By, Jacques Marc

Underwater Archaeological Society of British Columbia Vol. 33 No. 4 Last Quarter Texada Island - Sturt Bay Shipwreck Investigation A Report by, Jacques Marc The UASBC made a trip to Sturt Bay on Texada Island on October 15th 2017 to investigate three wrecks located by the Canadian Hydrographic Service during survey operations in the fall of 2016. Wreck coordinates and images were provided by Duncan Havens, a Multidisciplinary Hydrographer of the Canadian Hydrographic Service Canadian Hydrographic Multi-beam survey showing the three wrecks in Sturt Bay. Courtesy Canadian Hydrographic Service The least depth coordinates 49 45 .801N by 124 33 .657 W provided by CHS, put us on the stern of the wreck. TheOur tide first height dive wasat the completed time of our on dive Wreck was #1 5.3 which feet. Onlies this on Scotttide the Rock stern at the of theentrance wreck to was Sturt in 40Bay. feet of water found the barge to be 46 meters (151 ft) long by 13 meters (42.6 ft) wide. The barge is made of steel with low and the bow was in 90 feet of water. The wreck was identified as a steel open deck barge. Survey measurements Continued on page 2 Page 1 Texada Island - Sturt Bay Shipwreck Investigation(cont’d) sidewalls along the deck and was most likely used for gravel or other material, but could also have been used to transport equipment. The barge is almost identical in construction and design to the barge in the photo below. Https://commons.wikimedia.org Utility barge at Anchor, Powell River BC by its skegs. -

2018 General Local Elections

LOCAL ELECTIONS CAMPAIGN FINANCING CANDIDATES 2018 General Local Elections JURISDICTION ELECTION AREA OFFICE EXPENSE LIMIT CANDIDATE NAME FINANCIAL AGENT NAME FINANCIAL AGENT MAILING ADDRESS 100 Mile House 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Wally Bramsleven Wally Bramsleven 5538 Park Dr 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E1 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Leon Chretien Leon Chretien 6761 McMillan Rd Lone Butte, BC V0K 1X3 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Ralph Fossum Ralph Fossum 5648-103 Mile Lake Rd 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E1 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Laura Laing Laura Laing 6298 Doman Rd Lone Butte, BC V0K 1X3 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Cameron McSorley Cameron McSorley 4481 Chuckwagon Tr PO Box 318 Forest Grove, BC V0K 1M0 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 David Mingo David Mingo 6514 Hwy 24 Lone Butte, BC V0K 1X1 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Chris Pettman Chris Pettman PO Box 1352 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Maureen Pinkney Maureen Pinkney PO Box 735 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Councillor $5,000.00 Nicole Weir Nicole Weir PO Box 545 108 Mile Ranch, BC V0K 2Z0 100 Mile House Mayor $10,000.00 Mitch Campsall Heather Campsall PO Box 865 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Mayor $10,000.00 Rita Giesbrecht William Robertson 913 Jens St PO Box 494 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 100 Mile House Mayor $10,000.00 Glen Macdonald Glen Macdonald 6007 Walnut Rd 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E3 Abbotsford Abbotsford Councillor $43,928.56 Jaspreet Anand Jaspreet Anand 2941 Southern Cres Abbotsford, BC V2T 5H8 Abbotsford Councillor $43,928.56 Bruce Banman Bruce Banman 34129 Heather Dr Abbotsford, BC V2S 1G6 Abbotsford Councillor $43,928.56 Les Barkman Les Barkman 3672 Fife Pl Abbotsford, BC V2S 7A8 This information was collected under the authority of the Local Elections Campaign Financing Act and the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. -

For BUILT HERITAGE RESOURCES in the COLUMBIA BASIN INVENTORY and STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS

INVENTORY and STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS Touchstones Nelson Museum of Art & History 72-29-40 for BUILT HERITAGE RESOURCES in the COLUMBIA BASIN prepared for the COLUMBIA BASIN TRUST May 2016 INVENTORY and STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS for BUILT HERITAGE ASSETS in the COLUMBIA BASIN COLUMBIA BASIN TRUST Team Denise Cook Design James Burton, Birmingham & Wood Architects and Planners Stephanie Fischer, Diploma-Ingenieur (FH), Architektur (B.Arch) Contact: Denise Cook BCAHP Principal, Denise Cook Design 764 Donegal Place North Vancouver, BC V7N 2X7 Telephone: 604-626-2710 Email: [email protected] Nelson location: c/o Stephanie Fischer 707 Hoover Street Nelson, BC V1L 4X3 Telephone (250) 352-2293 Columbia Basin Trust Denise Cook Design • Birmingham & Wood 2 Heritage Inventory • Strategic Directions Stephanie Fischer TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction . 4 2.0 Thematic framework for the Columbia Basin . 6 3.0 Strategic Directions . 16 3.1 Trends in heritage conservation . 16 3.2 Regional and local planning context . 18 3.3 Heritage policies, programs, recommendations 20 3.4 Heritage resource selection process . 27 3.5 Potential case studies . 30 4.0 The Basin Inventory . 31 Valemount Museum. 4.1 Resource inventory map . 33 4.2 Inventory tables . 34 5.0 Selected Sources . 112 6.0 Appendices . 113 A: Glossary of terms B: Some identified place names of lost indigenous and newcomer resources C: Approaches to heritage conservation D: Heritage conservation planning process E: Nomination form for future resources Columbia Basin Trust Denise Cook Design • -

Bluebell Mine – Remediation of a Historic Mine Site

Proceedings of the 25th Annual British Columbia Mine Reclamation Symposium in Campbell River, BC, 2001. The Technical and Research Committee on Reclamation BLUEBELL MINE - REMEDIATION OF A HISTORIC MINE SITE BJ. Donald, P.Eng., Teck Cominco Metals Ltd. WJ. Kuit, Teck Cominco Metals Ltd. and N.L. Sandstrom, P.Eng., Morrow Environmental Consultants Inc. Teck Cominco Metals Ltd., 500 - 200 Burrard Street, Vancouver, BC Morrow Environmental Consultants Inc., 1125A Industrial Road #3, Cranbrook, BC ABSTRACT The Bluebell Mine was a lead, zinc and silver mine discovered circa 1820 that had been exploited by a number of owners until its final closure in 1972. It is located in the hamlet of Riondel, BC. Kootenay Lake surrounds the mine site on three sides. Cominco Ltd. acquired the surface and mineral rights in the 1930s and operated a mine and concentrator from 1952 to 1972. The mine was reclaimed to the standards of the day upon closure. In 1997, Cominco initiated a series of phased investigations to identify potential environmental and public safety issues at the site. The site contains waste rock dumps, process fines (residual tailings and concentrates) and deposits of Mine Water Discharge (MWD) fines that had been pumped to surface during mine operations. The process fines and MWD fines existed both on land and in Kootenay Lake, including the foreshore areas of Galena and Bluebell Bays. The site had surface and groundwater issues related to both Acid Rock Drainage (ARD) and neutral pH metal leaching (ML). In 2000, Cominco initiated a remedial program to substantially improve both the environmental and public safety aspects of the site. -

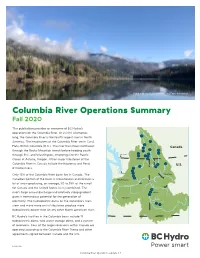

Columbia River Operations Summary Fall 2020

Pend d’Oreille Reservoir. Photo by Fabio Moscatelli. Columbia River Operations Summary Fall 2020 This publication provides an overview of BC Hydro’s operations on the Columbia River. At 2,000 kilometres long, the Columbia River is the fourth largest river in North America. The headwaters of the Columbia River are in Canal Flats, British Columbia (B.C.). The river then flows northwest Canada through the Rocky Mountain trench before heading south through B.C. and Washington, emptying into the Pacific Vancouver Ocean at Astoria, Oregon. Other major tributaries of the Columbia River in Canada include the Kootenay and Pend U.S. d’Oreille rivers. Seattle Only 15% of the Columbia River basin lies in Canada. The Montana Canadian portion of the basin is mountainous and receives a Washington lot of snow producing, on average, 30 to 35% of the runoff for Canada and the United States (U.S.) combined. The river’s large annual discharge and relatively steep gradient Idaho gives it tremendous potential for the generation of Oregon electricity. The hydroelectric dams on the Columbia’s main stem and many more on its tributaries produce more hydroelectric power than on any other North American river. BC Hydro’s facilities in the Columbia basin include 13 hydroelectric dams, two water storage dams, and a system of reservoirs. Four of the larger reservoirs within Canada are operated according to the Columbia River Treaty and other agreements signed between Canada and the U.S. BCH20-712 Columbia River Operations Update | 1 Columbia River Treaty compensated for energy losses at its Kootenay Canal operations that result from the timing of water releases The Columbia River Treaty between Canada and the United from the Libby Dam. -

FACTSHEET 2007EDU0059-000480 Ministry of Education May 25, 2007

FACTSHEET 2007EDU0059-000480 Ministry of Education May 25, 2007 STRONGSTART BC EXPANSION TO BENEFIT B.C. COMMUNITIES Strong Start BC centres must be located in schools with unused and underutilized space. TBD indicates school districts have yet to determine the exact location of their StrongStart BC centre. No. School District School(s) 5 Southeast Kootenay Amy Woodland elementary Steeples elementary 6 Rocky Mountain Alexander Park elementary 8 Kootenay Lakes Creston Education Centre 10 Arrow Lakes Nakusp elementary 19 Revelstoke Mountain View elementary 20 Kootenay-Columbia Fruitvale elementary 22 Vernon Harwood elementary 23 Central Okanagan A.S. Matheson elementary 27 Cariboo-Chilcotin 100 Mile House elementary Marie Sharpe elementary 28 Quesnel Riverview elementary 33 Chilliwack Little Mountain elementary Watson elementary 34 Abbotsford Alexander elementary Clearbrook elementary 35 Langley Nicomekl elementary Shortreed Community 36 Surrey Bridgeview elementary Cougar Creek elementary 37 Delta Hellings elementary McCloskey elementary 38 Richmond Mitchell elementary 39 Vancouver TBD TBD 40 New Westminster Queen Elizabeth elementary 41 Burnaby Edmonds Community Forest Grove elementary Morley elementary 42 Maple Ridge-Pitt Meadows Eric Langton elementary 43 Coquitlam Riverview Park elementary Roy Stibbs elementary 44 North Vancouver Westview elementary 45 West Vancouver Hollyburn elementary - 2 - No. School District School(s) 46 Sunshine Coast Sechelt elementary 47 Powell River James Thomson elementary Henderson elementary 48 Howe Sound -

The Village of Kaslo Celebrates 125 Years As an Incorporated Municipality

May 12, 2018 • VOL. II – NO. 1 • The Kaslo Claim The VOL.Kaslo II – NO. I • KASLO, BRITISH COLUMBIA • MAYClaim 12, 2018 The Village of Kaslo Celebrates 125 Years as an Incorporated Municipality by Jan McMurray are finding ways to celebrate Kaslo’s Kaslo Pennywise beginning on June decorated in Kaslo colours and flags The Langham has commissioned The municipality of Kaslo will quasquicentennial, as well. Can you 5. The person who finds the treasure from around the world, and guided Lucas Myers to write a one-man, reach the grand old age of 125 on guess the theme of Kaslo May Days will keep the handcrafted box and the walking tours of Kaslo River Trail. multimedia play, Kaslovia: A August 14, and a number of events this year? Watch for the Village’s float, $100 bill inside. A Treasure Fund is The North Kootenay Lake Arts Beginner’s Guide, which he will are being planned to celebrate this the mini Moyie, and the refurbished right now growing with donations, and Heritage Council will host perform on Friday, September 28 momentous occasion. Maypole float in the parade. There and is expected to exceed $1,500 by a special arts and crafts table on and Saturday, September 29 at the The Kaslo 125 Committee is will be new costumes handmade by the time the box is found. The bulk of August 11 at the Saturday Market. Langham. Myers’ one-man plays are planning a gala event at the Legion Elaine Richinger for the Maypole the fund will go to the finder’s charity People will be invited to do an on- simply too good to miss – mark your on Saturday, August 11 and a Street Dancers and new ribbons from of choice, with five per cent awarded the-spot art project with a Kaslo calendars now! Party on Fourth Street and City Hall England for the Maypole. -

Electoral Area 'B' Official Community Plan Bylaw No. 850

COLUMBIA SHUSWAP REGIONAL DISTRICT ELECTORAL AREA 'B' OFFICIAL COMMUNITY PLAN BYLAW NO. 850 THIS CONSOLIDATED BYLAW IS NOT INTENDED TO BE USED FOR LEGAL PURPOSES CONSOLIDATED FOR CONVENIENCE ONLY WITH BYLAW NO. 850-2 June 17, 2013 INFORMATION SHEET ON THE BYLAWS WHICH WERE CONSOLIDATED INTO BYLAW NO. 850 BYLAW NO. 850-2 – Adopted May 16, 2013 - Text amendments to Section 4.4.19 relating to Shelter Bay - New Sections added, Sections 4.4.26 to 4.4.55 – specific community policies and Development Permit Areas for Shelter Bay - Map Amendment Columbia Shuswap Regional District Electoral Area ‘B’ OFFICIAL COMMUNITY PLAN Planning for rural areas and communities including: Mica, Rural Revelstoke, Trout Lake, Beaton and Galena Bay Schedule A Bylaw 850 Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Legislative and Regulatory Context ................................................. 1 1.2 Community Consultation .................................................................. 2 1.3 Community Vision ............................................................................ 2 1.4 Plan Context .................................................................................... 3 1.5 General Implementation .................................................................. 5 1.6 Acronym Summary .......................................................................... 8 SECTION TWO: PLANNING STRATEGY 2.1 Growth Patterns ............................................................................... 10 2.2 Growth Projections .........................................................................