Nietzsche, Foucault, Yoga, and Feminist S/Self-Actualisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

125+ Free Streaming Workouts to Do at Home

125+ Free Streaming Workouts to Do From Home During Coronavirus March 25, 2020 – 10:30 AM Follow @ohheyjesssager By Jessica Sager @ohheyjesssager The coronavirus crisis has almost all of us stuck in our homes without access to a gym—but in order to stay healthy, boost our immunity and also just stay sane and relieve some stress, exercise is key. While it can be tough without friends or your usual trainers around to motivate you, you can still get great results at home with these free workouts. Whether you’re into Zumba, CrossFit or kickboxing, or working out alone or with your kids, you’ll find at least one avenue that will make you feel good inside and out while you’re social distancing. For the best free YouTube workouts, from free weight chest workouts to free dance workouts, or free BeachBody and yoga workouts, we’re rounding up all the best free workouts you can stream today. Check out the list for the best free workouts on YouTube, On Demand, ROKU, Amazon Prime, on Instagram/IGTV, on Facebook, as well as the best free workouts from gyms and fitness studios, and the best free kid workouts or yoga for kids. Free YouTube Workouts 567Broadway! 567Broadway! workouts, featuring choreography inspired by your favorite stage shows, are available for free on YouTube. Blocker Yoga Blocker Yoga classes range from seated meditation to higher-intensity yoga workouts, all with the goal of cultivating more mindfulness with intentional movement and centered presence. Boho Beautiful Boho Beautiful offers free yoga classes and meditation practices on YouTube. -

Sivananda Teacher Training Manual

Sivananda Teacher Training Manual If you are looking for a ebook Sivananda teacher training manual in pdf form, in that case you come on to faithful website. We present the full edition of this ebook in txt, doc, ePub, DjVu, PDF forms. You may reading Sivananda teacher training manual online or load. Additionally to this ebook, on our website you may reading the instructions and different art eBooks online, or download their as well. We want attract your regard that our website does not store the eBook itself, but we give reference to the website whereat you can download or reading online. So if you have must to downloading pdf Sivananda teacher training manual, then you have come on to the loyal website. We own Sivananda teacher training manual doc, ePub, txt, DjVu, PDF forms. We will be happy if you will be back us anew. Sivananda Yoga Teachers Training Course, - Looking for Yoga Teacher Training or Yoga Courses in GrassValley, California in USA? We could suggest the Sivananda Yoga Teachers Training Course, GrassValley Read Chair Yoga Teacher Training - Sivananda Yoga - Chair Yoga Teacher Training Stacie Dooreck (Saraswati) Member: $295.00 Non-member: $295.00 INCLUDES: 140+pg Teacher Training Manual and Certificate of Completion Teacher Training | - Chinook Yoga - With 20 years of experience training teachers and guided by the highest standards, Swami Sivananda) Download a sample of the SOYA 200hr Teacher Training Manual. Yoga Teachers' Training Course (TTC) - Sivananda - The Sivananda Ashram Yoga Ranch's Yoga Teacher Training Course (TTC) is one of the most well-rounded Yoga training programs in the West today. -

GLOSSARY of DIFFERENT YOGA STYLES (Updated 20Aug2018)

GLOSSARY OF DIFFERENT YOGA STYLES (Updated 20Aug2018) ACROYOGA is a type of yoga that combines traditional Hatha or Vinyasa Flow yoga with acrobatics. It originated in the late 1990s and has quickly become popular, with AcroYoga schools now all over the world. Partner work is a key feature of AcroYoga, and the work with a partner helps to improve strength and balance as well as building trust. It may also incorporate elements of massage which can relieve stress. ANUSARA: Founded in 1997 by John Friend, Anusara is heart-oriented, integrates celebration of the heart, alignment. With a more upbeat mood, Anusara focuses on mood enhancement and injury prevention and is especially great for beginners or out-of-shape practitioners. Beginner-friendly. ASHTANGA: An inspiration for many vinyasa-style yoga classes, and a more athletic method, Ashtanga is a traditional practice focused on progressive pose sequences tied to the breath. The Primary Series is made up of about 75 poses, takes about 90 minutes to go through and promotes spinal alignment, detoxification of the body, and building strength and flexibility. And there ain’t no stopping in this class— continuous flow is central to its practice. Founded by K. Pattabhi Jois (1915-2009), this system is taught around the world. Jois's grandson R. Sharath now leads the Shri K. Pattabhi Jois Ashtanga Yoga Institute in Mysore, India. BAPTISTE YOGA: It is physically challenging, flowing set sequence practice in a heated room that will get your heart pumping while also encouraging you to find your authentic personal power in life. Baron Baptiste, son of yoga pioneers Walt and Magana Baptiste (who opened San Francisco's first yoga center in 1955), began practicing as a child and studied with many Indian yoga masters. -

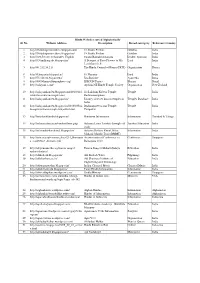

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Yoga in the Modern World: the Es Arch for the "Authentic" Practice Grace Heerman University of Puget Sound

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Sociology & Anthropology Theses Sociology & Anthropology May 2014 Yoga in the Modern World: The eS arch for the "Authentic" Practice Grace Heerman University of Puget Sound Follow this and additional works at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/csoc_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Heerman, Grace, "Yoga in the Modern World: The eS arch for the "Authentic" Practice" (2014). Sociology & Anthropology Theses. 5. https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/csoc_theses/5 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology & Anthropology at Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology & Anthropology Theses by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Yoga in the Modern World: The Search for the “Authentic” Practice Grace Heerman Asia 489, Independent Research Project Advisor: Prof. Sunil Kukreja 13 April, 2012 Heerman, 2 Introduction Since its early twentieth century debut into Western consciousness, yoga has quickly gained widespread appeal, resonating in the minds of the health-conscious, freedom-seeking American public. Considered to be the “spiritual capital” with which India hoped to garner material and financial support from the West, yoga was originally presented by its Eastern disseminators as “an antidote to the stresses of modern, urban, industrial life” and “a way to reconnect with the spiritual world” without having to compromise the “productive capitalist base upon which Americans [stake] their futures.”1 Though exact practitioner statistics are hard to come by, it is clear that the popularity of yoga in the U.S. -

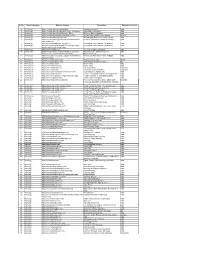

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilization Indus Valley Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 4 Archaelogy http://www.ancientworlds.net/aw/Post/881715 Ancient Vishnu Idol Found in Russia Russia 5 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/ Archeological Evidence of Vedic System India 6 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/scientific- Scientific Verification of Vedic Knowledge India verif-vedas.html 7 Archaelogy http://www.ariseindiaforum.org/?p=457 Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India 8 Archaelogy http://www.dwarkapath.blogspot.com/2010/12/why- Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India dwarka-submerged-in-water.html 9 Archaelogy http://www.harappa.com/ The Ancient Indus Civilization India 10 Archaelogy http://www.puratattva.in/2010/10/20/mahendravadi- Mahendravadi – Vishnu Temple of India vishnu-temvishnu templeple-of-mahendravarman-34.html of mahendravarman 34.html Mahendravarman 11 Archaelogy http://www.satyameva-jayate.org/2011/10/07/krishna- Krishna and Rath Yatra in Ancient Egypt India rathyatra-egypt/ 12 Archaelogy http://www.vedicempire.com/ Ancient Vedic heritage World 13 Architecture http://www.anishkapoor.com/ Anish Kapoor Architect London UK 14 Architecture http://www.ellora.ind.in/ Ellora Caves India 15 Architecture http://www.elloracaves.org/ Ellora Caves India 16 Architecture http://www.inbalistone.com/ Bali Stone Work Indonesia 17 Architecture http://www.nuarta.com/ The Artist - Nyoman Nuarta Indonesia 18 Architecture http://www.oocities.org/athens/2583/tht31.html Build temples in Agamic way India 19 Architecture http://www.sompuraa.com/ Hitesh H Sompuraa Architects & Sompura Art India 20 Architecture http://www.ssvt.org/about/TempleAchitecture.asp Temple Architect -V. -

Amy Tobey Hotmessyogi.Com | [email protected]

Amy Tobey hotmessyogi.com | [email protected] SummaryYoga woke me up. It’s a practice and always will be. So is life… Take risks, find balance, and learn what it feels like to simply surrender to what is. Fall in love with whatever unfolds. Smile, listen, breathe. Be awake to this moment. Live your live with love, and you will then love your life. Experience Summer 2016 | Co-led Barefoot Power Teacher Training October 2013-present | Instructor at Barefoot Yoga Loft October 2013 | Opened Barefoot Yoga Loft as co-owner Education September 2016 | Alexandria Crow- Yoga Physics/Anatomy August 2016 | Kathryn Budig, AimTrue- Arm Balances, Inversions, Flow, & Discussions January 2016 | Deborah Adele- Author of Yamas and Niyamas, Discussion of Yamas & Niyamas November 2015 | Live Love Teach/Stacy Dockins- Yoga Anatomy August 2015 | Rainbow Kids Yoga March 2015 | Breast Cancer Yoga with Angela Strynkowski August 2014 | Kathryn Budig, Aim True- Arm Balances, Inversions, & Discussions July 2014 | Karma Kids Yoga,-Yoga for Teens May 2014 | Rachel Brathen-Arm Balances & Flow March 2014 | Jason Crandall-Practicing Crow & Handstands January 2014 | Childrens Yoga with Mira Benzen January 2014 | Live Love Teach 300 hr. teacher training: Stacy Dockins & Philip Urso- Anatomy, “Spiritu- ality”, “Unhindered and Unbound”- teaching with authenticity, direct awareness, & synchronized breath December 2013 | Tias Little-Hips & Rotator Cuffs August 2013 | Kathryn Budig- Arm Balances June 2013 | Kino McGregor-Ashtanga Yoga January 2013 | Yoga Sculpt Training at Corepower Yoga October 2012 | Seane Corn teacher Training October 2012 | Pregnancy Practice with Cassie Rodgers April 2012 | Hot Power Fusion Yoga Training at Corepower Yoga March 2012 | 200 hr Vinyasa Teacher Training at Corepower Yoga Examples of Workshops Affiliations A Practice of Your Senses October 2013- Present | Yoga Alliance Mindfulness Over 900 hours of experience Arm Balance & Inversions Back to Basics Yoga Nidra Full list available upon request. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Gillian Eliza Yoga

Gillian Eliza [email protected] www.GillianElizaYoga.com IG: @gillianeliza E-RYT 200, Trauma Informed Yoga Teacher Teaching Style Influenced by my trauma informed training, I am committed to providing students the space to access their true yoga practice mentally and physically. Using yogic principles such as breath, physical asana, and meditation, we can truly learn to not only appreciate ourselves but also learn to meet ourselves exactly where we are right now. Training/Credentials Continuing Education: Advanced Sequencing, Assisting, & Meditation Carmen & Moises Aguilar April 2018 - The Lab Chicago Carmen & Moises Aguilar approach sequencing and assisting from an intelligent, alignment based approach. This four-day training delved into sequencing to multiple peak poses, learning Carmen’s CYoga Ashtanga influenced style of teaching, and advanced intentional hands-on adjusts/assists. 65-hour Trauma Informed Yoga Therapy/Overcome Anxiety Clinic: Sundara Yoga Therapy October 2016 - Dallas, TX Trauma Informed Yoga Therapy provides students with the support to feel safe in an environment where they can delve in to their bodies to help cope with anxiety, trauma, PTSD, and stress. Through scientific and yogic techniques: breath work, physical movement, understanding how the body processes anxiety/stress, and positive affirmations. Students can begin to reprogram their responses to anxiety and trauma, helping bring them calm as well as help to resolve issues alongside their mental health professional. 200-hour Yoga Teacher Training: CorePower Yoga Beginner to Advanced Vinyasa: C1/C2, Hot Power Fusion, Yoga Sculpt October 2014 – November 2016 Chicago, IL | Austin, TX CorePower Yoga training provided many different yoga styles to use with students. -

YOGA JOURNAL Spain

¡¡NUEVO!! Imágenes vivas para saber cómo practicar cada asana J OURNAL pNº 56 f^X Testimonio Judith Secanell, actriz y bailarina µGk[i “Tan despierta, tan [baWhcW5 viva, ¡vibraba!” µGkfk[Z[i ^WY[hYed [bjkoe5 /cel_c_[djei fWhWkdWiheZ_bbWi" f_[io^ecXheiiWdei Cuerpo equilibrado EN 5 POSTURAS :[Yce EYY_Z[dj[i[ +[dWcehZ[bW?dZ_W 01 PORTADA 56.indd 1 27/2/13 11:54:23 publi yoga.indd 1 27/2/13 12:05:06 sumario 38 ¡¡NUEVO!! Imágenes vivas para saber cómo practicar cada asana J OURNAL pf^X Testimonio Judith Secanell, actriz y bailarina µ G k [ i “Tan despierta, tan [ b a W h c W 5 viva, ¡vibraba!” µGkfk[Z[i ^ W Y [ h Y e d [ b j k o e 5 /cel_c_[djei fWhWkdWiheZ_bbWi" f_[io^ecXheiiWdei Cuerpo equilibrado EN 5 POSTURAS :[Yce EYY_Z[dj[i[ +[dWcehZ[bW?dZ_W en portada Cuerpo equilibrado en 5 posturas (66) ¿Qué es el karma? ¿Qué puedes hacer con (8) 66 foro del lector el tuyo? (43) Un rincón para compartir experiencias. 9 movimientos para unas rodillas, pies y (9) consultorio hombros sanos (52) Un nuevo consultorio sobre yoga terapéutico, respondido por Alex Monasterio, De cómo Occidente se vicepresidente de la Asociación Española de enamoró de la India (71) Yoga Terapéutico (AEYT). Testimonio Judith Secanell “Tan om (11) despierta, tan viva, Novedades para sentirte mejor, cuidar tu ¡¡vibraba!!” (29) cuerpo, nuevos complementos y alimentos... comer bIen ve al grano (25) 25 Las sutiles diferencias de sabor y textura hacen de los granos integrales un placer culinario. TeSTImOnIO tan despierta, tan viva, vibraba!! (29) Créditos de portada Judith Secanell, actriz y bailarina, hizo del Modelo:Anne O’Brien in yoga una filosofía de vida. -

Press Kit Feb13 Small.Pdf

Press Kit I. Cover Page II. Table of Contents III. About CPY (Our Story - key milestones ) a. Our Mission & Karma Yoga b. Our Management Team IV. Testimonials V. FAQs VI. Our Trademark VII. Media Contacts table of contents Our Story: When a serious climbing accident left him with six permanent screws in his shattered ankle, CorePower Yoga Founder and CEO Trevor Tice experienced first hand the transformational benefits of yoga. An avid outdoorsman from Telluride, CO, Trevor was left searching for an exercise to replace the running, climbing and other physically challenging activities no longer accessible to him. He found yoga, and was hooked. Traveling for his technology business, Trevor practiced a variety of yoga disciplines at yoga studios across the country and found an opportunity to make yoga dynamic, challenging and accessible. In 2002, Trevor opened the first CorePower Yoga studio on Grant Street in downtown Denver, Colorado, offering a proprietary form of athletic, heated yoga in modern, welcoming and spa-like studios. With six teachers, including Trevor, teaching four classes per day, it took several arduous months before classes began to fill up. But they did. And it wasn’t long before people were talking about this new Yoga. Our Mission: Share our authentic passion for yoga and healthy living to inspire everyone to live their most extraordinary life. Key Milestones: 2006: CorePower Yoga – Point Loma opens 2011: CPY opened its first Bay Area studio in San Diego, CA in Berkeley, in addition to three studios in 2004: CorePower Yoga acquires South San Diego, two studios in L.A., one in Orange Boulder, Cherry Hills and Broadway studios 2007: CorePower Yoga introduced The County, and two in Chicago. -

2019 Syllabus Vinyasa

PHYS ED 1, 2, 3 YOGA: VINYASA PHYS ED 1, 2, 3 - VINYASA YOGA (0.05 units) Instructor: Toni Mar http://pe.berkeley.edu/instructors_toni_mar.html https://www.yogatrail.com/teacher/toni-mar-1384324 http://www.ratemyprofessors.com/ShowRatings.jsp?tid=312615 https://berkeley.uloop.com/professors/view.php/56459/Toni-Mar Contact: e: [email protected] p: 1.510.642.2375 Office: 225 Hearst Memorial Gymnasium Office Hours: Tuesday 9:15-10:00 with advance reservation or congruent availability Required Material: Syllabus contents, videos and links via bCourse I. Course Description: Ashtanga Yoga (“eight-limbed yoga”; ashta=eight, anga=limb) is a system of yoga that emphasizes vinyasa: the synchronization of the breath with movement to produce inner heat, known as tapas, to purifiy the blood, detoxify the muscles and internal organs, and improve circulation. This style of yoga as it is practiced on the mat is also referred to as Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga but within the Ashtanga community of practitioners we simply say Ashtanga Yoga. The “eight limbs of Ashtanga” per se lead the path towards internal purification which is necessary for attaining self-realization. These eight spiritual paths or limbs are: Yama (moral codes), Niyama (self- purification and study), Asana (posture), Pranayama (breath control), Pratyahara (withdrawing the senses), Dharana (concentration), Dhyana (meditation), and Samadhi (meditative consciousness). Asana, the third limb, is known as Hatha Yoga.“Ha” means Sun, “Tha” Moon, and represent the search for balance in the union of opposing forces. All of the eight limbs are integral to the vinyasa practice, i.e. “ashtanga vinyasa yoga” and are the foundations for developing a strong yoga practice and guiding the practitioner while on the mat.