Tracing an American Yoga: Identity and Cross-Cultural Transaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Academy, Madras 115-E, Mowbray’S Road

Tyagaraja Bi-Centenary Volume THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. XXXIX 1968 Parts MV srri erarfa i “ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, nor in the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada l ” EDITBD BY V. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1968 THE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD. MADRAS-14 Annual Subscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. iI i & ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES ►j COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page Back (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 20 11 Back (Do.) „ 30 „ 16 INSIDE PAGES: 1st page (after cover) „ 18 „ io Other pages (each) „ 15 „ 9 Preference will be given to advertisers of musical instruments and books and other artistic wares. Special positions and special rates on application. e iX NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editor, Journal Of the Music Academy, Madras-14. « Articles on subjects of music and dance are accepted for mblication on the understanding that they are contributed solely o the Journal of the Music Academy. All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably type written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and should >e signed by the writer (giving his address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by individual contributors. All books, advertisement moneys and cheques due to and intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V. Raghavan Editor. Pages. -

Can One Achieve Self-Realization Through Asana Practice? | Dharma Mittra

Can One Achieve Self-Realization Through Asana Practice? | Dharma Mittra by Dharma Mittra June 13, 2013 0 Like 180 Share Tweet “A qualified yoga teacher will know which practice is fit for each student.”~ Yogi Sri Dharma Mittra Some Answers From Yogi Sri Dharma Mittra – Interview By Adam Frei Adam Frei: For many practitioners today, yoga seems to mean Asana practice. Are you concerned over this trend? Can people achieve Self-realization just through Asana practice? Dharma Mittra: Asanas are an aid to facilitate the journey to Self-realization within the yoga system. The postures are designed to induce a specific state of consciousness according to their geometric shape. In actual practice, certain Asanas are combined with Mudras, Bandhas, Pranayama, visualizations and intense attention on some of the Chakras or glands, etc., thus enhancing mental abilities (concentration). But, Asanas are unable to destroy the subtle impurities of the mind that only keeping Yama (the Ethical Laws) and Niyama (the Yogic Observances) can. Yama and Niyama are the first and second steps of Ashtanga or Classical Eight-limbed Yoga and, without keeping them, there can be no Self- realization or true success in yoga. Based on what I’ve observed teaching for almost 50 years now, I would guess that only 1 out of 10 yoga students are really seeking Self-realization. The others are busy and very active with the Asanas just for the sake of improving their health, physique, mental powers and, up to some degree, their self-control also. All of this activity is engaged in for one purpose: so that they can better cope with their personal stuff so as to reduce their overall pain and suffering. -

Prop Technology Upcoming Workshops

Upcoming Workshops – continued from cover Summer 2012 Mary Obendorfer and Eddy Marks Janet MacLeod Patricia Walden 5-Day Intermediate Intensive October 19 – 21, 2012 February 1 – 3, 2013 June 19 – 23, 2013 Boise Yoga Center, Boise, ID Tree House Iyengar Yoga, Seattle, WA Yoga Northwest, Bellingham, WA www.boiseyogacenter.com www.thiyoga.com www.yoganorthwest.com 208.343.9786 206.361.9642 360.647.0712 *member discount available* Carolyn Belko Joan White October 19 – 21, 2012 Yoga and Scoliosis with Rita Lewis-Manos October 18 – 20, 2013 Mind Your Body, Pocatello, ID March 15 – 17, 2013 Tree House Iyengar Yoga, Seattle, WA www.mybpocatello.com/home Rose Yoga of Ashland, Ashland, OR www.thiyoga.com Prop Technology 208.234.220 roseyogacenter.com 206.361.9642 2012 IYANW Officers: by Tonya Garreaud 541.292.3408 *member discount available* Anne Geil - President Chris Saudek Marcia Gossard - Vice President It might come as a surprise to people who know me that the first thing I reach for each morning is my November 16 – 18, 2012 Carrie Owerko Karin Brown - Treasurer & Grants smart phone. After all, I was a late adopter—I still don’t hand out my cell number very often—I prefer Julie Lawrence Yoga Center, Portland, OR June 14 – 16, 2013 Angela McKinlay - Secretary not to be bothered. In general, I’m not a fan of cell phones. It is extremely difficult for me to maintain www.jlyc.com Julie Lawrence Yoga Center, Portland, OR Tonya Garreaud - Membership Chair equanimity when I see poor driving caused by the distracting use of a cell phone. -

Die Wurzeln Des Yoga Haṭha Yoga Teil 2

Die Wurzeln des Yoga Haṭha Yoga Teil 2 as tun wir eigentlich, wenn wir Âsanas üben? WWie begründen wir, dass die Praxis einer bestimmten Haltung Sinn macht? Worauf können wir uns stützen, wenn wir nach guten Gründen für das Üben eines Âsanas suchen? Der Blick auf die vielen Publikationen über Yoga zeigt: Bei den Antworten auf solche Fragen spielt – neben dem heutigen wissenschaftlichen Kenntnisstand – der Bezug auf die lange Tradition des Yoga immer eine wichtige Rolle. Aber sind die Antworten, die uns die alten mündlichen und schriftlichen Traditionen vermitteln, befriedigend, wenn wir nach dem Sinn eines Âsanas suchen? Was können wir von der Tradition wirklich lernen und was eher nicht? Eine transparente und nachvollziehbare Erklärung und Begründung von Yogapraxis braucht eine ernsthafte Reflexion dieser Fragen. Dafür ist ein auf Fakten gründender, ehrlicher und wertschätzender Umgang mit der Tradition des Ha†hayoga unverzichtbar. Dabei gibt es einiges zu beachten: Der physische Teil des Ha†hayoga beinhaltet keinen ausgewiesenen und fest 6 VIVEKA 57 Die Wurzeln des Yoga umrissenen Kanon bestimmter Âsanas, auch wenn bis heute immer wieder von „klassischen Âsanas“ die Rede ist. Auch gibt es kein einheitliches und fest umrissenes Konzept, auf das sich die damalige Âsanapraxis stützte. Vielmehr zeigt sich der Ha†hayoga als Meister der Integration verschiedenster Einflüsse und ständiger Entwicklung und Veränderung. Das gilt für die Erfindung neuer Übungen mit ihren erwarteten Wirkungen wie auch für die großen Ziele der Yogapraxis überhaupt. Um die Tradition des Ha†hayoga zu verstehen reicht es nicht, einen alten Text nur zu zitieren. Es bedarf vielmehr eines Blickes auf seine Entwicklung und Geschichte. -

Focus of the Month 2.14

Bobbi Misiti 2201 Market Street Camp HIll, PA 17011 717.443.1119 befityoga.com TOPIC OF THE MONTH February 2014 FROM NOW FORWARD . AND SOME NOTES FROM MAUI Although I am not a “big fan” of the sutras, I do like to study them. Just because something was written as an “ancient text” does not always mean it has merritt . and in just the same way -- because some study proves some scientific “fact”, does not mean it is truth. For example all those years we thought saturated fat was bad for us . it is not! Studies were mis-read, mis-leading, politically adjusted, and “interpretations” seem to benefit some benefactor more than mankind. However I like this little blip from David Life on the very first sutra, in my simple words it basically says: From now on, just allow the yoga to arise naturally in you :) Excerpts from David Life's January 2014 focus of the month -- Jivamukti Yoga Atha yoga-anushasanam (Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra 1:1) Now this is yoga as I have perceived it in the natural world. Atha means “now.” But it’s more than just “now”; it means now in terms of “hereafer,” or “going forward.” The importance of that nuance is that it implies that whatever has been happening will now, hereafer, be different. The word shasanam can be understood as a set of rules, a discipline applied to us from the outside, a set of instructions for what we’re supposed to do next. But when we put the word anu, which literally means “atom,” in front of it, it means the instructions or ways to act that come from the inside. -

Preserving and Protecting Mysore Heritage Tmt

Session – I Preserving And Protecting Mysore Heritage Tmt. Neela Manjunath, Commissioner, Archaeology, Museums and Heritage Department, Bangalore. An introduction to Mysore Heritage Heritage Heritage is whatever we inherit from our predecessors Heritage can be identified as: Tangible Intangible Natural Heritage can be environmental, architectural and archaeological or culture related, it is not restricted to monuments alone Heritage building means a building possessing architectural, aesthetic, historic or cultural values which is identified by the heritage conservation expert committee An introduction to Mysore heritage Mysore was the capital of princely Mysore State till 1831. 99 Location Mysore is to the south-west of Bangalore at a distance of 139 Kms. and is well connected by rail and road. The city is 763 meters above MSL Princely Heritage City The city of Mysore has retained its special characteristics of a ‘native‘princely city. The city is a classic example of our architectural and cultural heritage. Princely Heritage City : The total harmony of buildings, sites, lakes, parks and open spaces of Mysore with the back drop of Chamundi hill adds to the attraction of this princely city. History of Mysore The Mysore Kingdom was a small feudatory of the Vijayanagara Empire until the emergence of Raja Wodeyar in 1578. He inherited the tradition of Vijayanagara after its fall in 1565 A.D. 100 History of Mysore - Dasara The Dasara festivities of Vijayanagara was started in the feudatory Mysore by Raja Wodeyar in 1610. Mysore witnessed an era of pomp and glory under the reign of the wodeyars and Tippu Sultan. Mysore witnessed an all round development under the visionary zeal of able Dewans. -

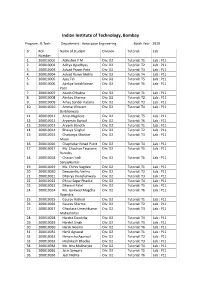

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2015 Bodies Bending Boundaries: Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks Kimberley J. Pingatore As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Pingatore, Kimberley J., "Bodies Bending Boundaries: Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks" (2015). MSU Graduate Theses. 3010. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3010 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BODIES BENDING BOUNDARIES: RELIGIOUS, SPIRITUAL, AND SECULAR IDENTITIES OF MODERN POSTURAL YOGA IN THE OZARKS A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, Religious Studies By Kimberley J. Pingatore December 2015 Copyright 2015 by Kimberley Jaqueline Pingatore ii BODIES BENDING BOUNDARIES: RELIGIOUS, SPIRITUAL, AND SECULAR IDENTITIES OF MODERN POSTURAL YOGA IN THE OZARKS Religious Studies Missouri State University, December 2015 Master of Arts Kimberley J. -

Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS

Breath of Life Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS Prana Vayu: 4 The Breath of Vitality Apana Vayu: 9 The Anchoring Breath Samana Vayu: 14 The Breath of Balance Udana Vayu: 19 The Breath of Ascent Vyana Vayu: 24 The Breath of Integration By Sandra Anderson Yoga International senior editor Sandra Anderson is co-author of Yoga: Mastering the Basics and has taught yoga and meditation for over 25 years. Photography: Kathryn LeSoine, Model: Sandra Anderson; Wardrobe: Top by Zobha; Pant by Prana © 2011 Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy of the U.S.A. All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of editorial or pictorial content in any manner without written permission is prohibited. Introduction t its heart, hatha yoga is more than just flexibility or strength in postures; it is the management of prana, the vital life force that animates all levels of being. Prana enables the body to move and the mind to think. It is the intelligence that coordinates our senses, and the perceptible manifestation of our higher selves. By becoming more attentive to prana—and enhancing and directing its flow through the Apractices of hatha yoga—we can invigorate the body and mind, develop an expanded inner awareness, and open the door to higher states of consciousness. The yoga tradition describes five movements or functions of prana known as the vayus (literally “winds”)—prana vayu (not to be confused with the undivided master prana), apana vayu, samana vayu, udana vayu, and vyana vayu. These five vayus govern different areas of the body and different physical and subtle activities. -

Introduction and Background to the Article on the Future of Yoga in the West

Introduction and background to the article on the future of Yoga in the West **updated version from 03.12.16, since first publishing** I began this project (which is now much more of a process) on a (seemingly) simple request to write an article on the future of Yoga in the west for Hindu Human Rights. Knowing yet another firstperson “State of the (Yoga) Union” address would essentially have zero value in light of the bigger issues in western Yoga world, I decided to base the project around a series of interviews with different people who had been involved in the discussion of how we got to where we are, i.e., this “Wild West, anything goes” concept of Yoga. Suffice it to say, as the conversations began, the project became infinitely more complex. Each one of the interviews highlighted something specific to framing the issues; each of the voices provided a myriad of “jumping off” points for further investigation and research. And with many other key collaborators besides the interviewees also involved, the depth and complexity of the topic expanded incredibly. Really, the “digging into” the topic could go on forever, but at a certain point the “getting it out” needs to take precedence in light of all that is at stake here. All that said, given the extensive subject matter and all of the nuance and information involved as well as all that has arisen throughout the process of interviews and related research the future of Yoga in the west article will be published in a series of three parts: Part I (as follows herein), “Adharmic Alliance: How the ivory tower helped Yoga Alliance “certify” Yoga as secular and detach it from its Hindu roots”: ● The first part frames the issues of Yoga in the west, and specifically the westernization of Yoga, around a case study of “Sedlock v. -

50 Things to Know About Yoga: a Yoga Book for Beginners

50 THINGS TO KNOW BOOK SERIES REVIEWS FROM READERS I recently downloaded a couple of books from this series to read over the weekend thinking I would read just one or two. However, I so loved the books that I read all the six books I had downloaded in one go and ended up downloading a few more today. Written by different authors, the books offer practical advice on how you can perform or achieve certain goals in life, which in this case is how to have a better life. The information is simple to digest and learn from, and is incredibly useful. There are also resources listed at the end of the book that you can use to get more information. 50 Things To Know To Have A Better Life: Self-Improvement Made Easy! by Dannii Cohen ______________________________________________ This book is very helpful and provides simple tips on how to improve your everyday life. I found it to be useful in improving my overall attitude. 50 Things to Know For Your Mindfulness & Meditation Journey by Nina Edmondso _____________________________________________ Quick read with 50 short and easy tips for what to think about before starting to homeschool. 50 Things to Know About Getting Started with Homeschool by Amanda Walton I really enjoyed the voice of the narrator, she speaks in a soothing tone. The book is a really great reminder of things we might have known we could do during stressful times, but forgot over the years. - HarmonyHawaii 50 Things to Know to Manage Your Stress: Relieve The Pressure and Return The Joy To Your Life by Diane Whitbeck ______________________________________________ There is so much waste in our society today. -

{PDF} a History of Modern Yoga: Patanjali and Western Esotericism

A HISTORY OF MODERN YOGA: PATANJALI AND WESTERN ESOTERICISM Author: Elizabeth de Michelis Number of Pages: 302 pages Published Date: 12 Nov 2005 Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9780826487728 DOWNLOAD: A HISTORY OF MODERN YOGA: PATANJALI AND WESTERN ESOTERICISM A History of Modern Yoga: Patanjali and Western Esotericism PDF Book NET, we will deal with storing and retrieving unstructured data with Blobs, then will move to Tables to insert and update entities in a structured NoSQL fashion. The authors engage in practical applications of ideas and approaches, and present a rigorous and informed view of the subject, that is at the same time professionally and practically focused. It also includes: Wiimote Remote Control car: Steer your Wiimote-controlled car by tilting the controller left and right; Wiimote white board: Create a multi-touch interactive white board; and, Holiday Lights: Synchronize your holiday light display with music to create your own light show. Silver was formed through the supernovas of stars, and its history continues to be marked by cataclysm. Choose from filling and tasty pasta rice meals, super fast pancakes frittatas, dips, dressings, pour over sauces more. Picture Yourself Networking Your Home or Small OfficeThis is the definitive guide for Symbian C developers looking to use Symbian SQL in applications or system software. 1 reason for workplace absence in the UK. An Ivey CaseMate has also been created for this book at https:www. As such, it fills a major gap in the study of how people learn and reason in the context of particular subject matter domains and how instruction can be improved in order to facilitate better learning and reasoning.