ROCI East: Rauschenberg's Encounters in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standoff at Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: the Making of Goddess of Democracy

2019/4/23 Standoff At Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy 更多 创建博客 登录 Standoff At Tiananmen How Chinese Students Shocked the World with a Magnificent Movement for Democracy and Liberty that Ended in the Tragic Tiananmen Massacre in 1989. Relive the history with this blog and my book, "Standoff at Tiananmen", a narrative history of the movement. Home Days People Documents Pictures Books Recollections Memorials Monday, May 30, 2011 "Standoff at Tiananmen" English Language Edition Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy Click on the image to buy at Amazon "Standoff at Tiananmen" Chinese Language Edition On May 30, 1989, the statue Goddess of Democracy was erected at Tiananmen Square and became one of the lasting symbols of the 1989 student movement. The following is a re-telling of the making of that statue, originally published in the book Children of Dragon, by a sculptor named Cao Xinyuan: Nothing excites a sculptor as much as seeing a work of her own creation take shape. But although I was watching the creation of a sculpture that I had had no part in making, I nevertheless felt the same excitement. It was the "Goddess of Democracy" statue that stood for five days in Tiananmen Square. Until last year I was a graduate student at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, where the sculpture was made. I was living there when these events took place. 点击图像去Amazon购买 Students and faculty of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, which is located only a short distance from Tiananmen Square, had from the beginning been actively involved in the demonstrations. -

Andreas Schmid Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT ANDREAS SCHMID Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise, Anthony Yung Date: 27 Apr 2008 Duration: about 2 hours Location: Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong Question (Q): Why did you go to China? Where you and what were you doing? Who are some of the artists that you encountered and what do you think about them? What were the artists reading and what are your comments on those materials? Andreas Schmid (AS): I graduated from the Art Academy in Stuttgart in 1981, studying painting. My paintings were, at that time, very different from German painters like Kiefer in that they always have free space, and transparency of layers of space in them. I painted with oil and acrylic, and it was different from my colleagues/contemporaries. I became interested in the idea of space, of Chinese Art, classical Chinese art, like Ni Zan [倪赞] in the fourteenth century. Then I went to Cologne and saw a collection of Japanese Buddhist writings collected by Seiko Kono , abbot of the Daian-ji temple in Nara City , Japan. I would like to know the line from another side, because lines played the most important role graphically in my paintings. So I tried contacting organizations that would support me, and they informed me there was only one woman who went to China as an artist from Germany with the support of the German exchange service. I went to see her, and she had studied in Hangzhou one year ago at that time (1980). She studied birds and flowers painting. She told me, if you want to do this, you should go to China, it is interesting. -

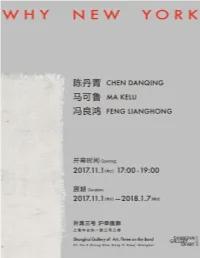

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

View Map of Healing Garden Artwork

Mark Ackerman • Nicolas Africano • Yaacov Agam • Jonathan Agger • Anni Albers • Josef Albers • Lita Albuquerque • Pierre Alechinsky • Peter Alexander • Elray Alkristy • Otmar Alt • John Altoon • Amos Amit • Othello Anderson • Michael Ansell • Karel Appel • Shusaku Arakawa • Cynthia Archer • Ardison Phillips • Jim Arkatov • Arman • Robert Arneson • Charles Arnoldi • Lisa Aronzon • Fred Arundel • Tadashi Asoma • Chet Atkins • Mario Avanti • Judith Azur • Olle Baertling • Claude Baillargeon • Richard Baker • Micha Bar-Am • Lynda Barckert • Lionel Barrymore • Frank Barsotti • Frank Beatty • David Marc Belkin • Gerald Belkin • Larry Bell • Mark Bellog • Lynda Benglis • Billy Al Bengston • Fletcher Benton • Dimitrie Berea • Don Berger • Joseph Bergler, The Younger • Elizabeth V. Blackadder • Lucienne Bloch • Karl Blossfeldt • Howard Bond • John Robert Borgstahl • Jonathan Borofsky • Richard Bosman • Paul Brach • Matthew Brady • Charles Bragg • Warren Brandt • Bettina Brendel • Ernest Briggs • Charlie Brown • Christopher Brown • James Paul Brown • Jerry Burchman • Hans Burkhardt • Bob Burley • Sakti Burman • Jerry Byrd • Alexander Calder • Jo Ann Callis • Tom Carr • Stuart Caswell • Marc Chagall • Judy Chicago • Christo • Clutie • Jodi Cobb • Jean Cocteau • Bruce Cohen • Larry Cohen • Chuck Connelly ARTIST • Greg / WORKConstantine • Ron Cooper • Greg Copeland • Amy Cordova • Sam Coronado • Steven Cortright • Robert Cottingham • Arnold Crane • Barbara Crane • Jeff Crisman • Chris Cross • Yvonne Cross • Ford Crull • Woody Crumbo • William Crutchfield -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Asia Society Hong Kong Center Presents

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Asia Society Hong Kong Center presents Light Before Dawn: Unofficial Chinese Art 1974-1985 On view at Asia Society Gallery (Former Magazine A) May 15 - September 1, 2013 (Hong Kong, May 13, 2013) Asia Society Hong Kong Center today announced that Light Before Dawn: Unofficial Chinese Art 1974 – 1985, will be unveiled to audiences at Asia Society Hong Kong Center from May 15-September 1. The exhibition offers a revealing look into the spectrum of work created by three of China’s most influential contemporary art groups: Wuming (No Name), Xingxing (Stars), and Caocao (Grass Society). Light Before Dawn presents the works of twenty-two artists from the three art groups of Wuming, Xingxing and Caocao, emerged from the Cultural Revolution, who sought artistic truth in the authenticity of human desire, pain and dreams, explored the personal meaning of creativity, and asserted the value of the individuals. Crossing the boundaries of subject matter and style, they questioned, re-evaluated and redefined the forms, the nature of beauty and the art of China. Distinctive in their art approaches, the Wuming group retained an interest in representations of nature, the Xingxing group explored historically Western modes of modernism, absorbing anew, progressive styles developed in Europe and America during the early twentieth century, including surrealism, cubism, and abstract expressionism while the Caocao group, trained in the native medium of ink and color on paper, attempted to shed both the legacy of socialist realism and the burdens of tradition by turning to new forms of abstract ink painting. Although each movement took a distinctly different artistic approach, they were united in their commitment to pushing Chinese art beyond the borders of Socialist Realism. -

The Political Repression of Chinese Students After Tiananmen A

University of Nevada, Reno “To yield would mean our end”: The Political Repression of Chinese Students after Tiananmen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Katherine S. Robinson Dr. Hugh Shapiro/Thesis Advisor May, 2011 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by KATHERINE S. ROBINSON entitled “To Yield Would Mean Our End”: The Political Repression Of Chinese Students After Tiananmen be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Hugh Shapiro, Ph.D, Advisor Barbara Walker, Ph.D., Committee Member Jiangnan Zhu, Ph.D, Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Associate Dean, Graduate School May, 2011 i ABSTRACT Following the military suppression of the Democracy Movement, the Chinese government enacted politically repressive policies against Chinese students both within China and overseas. After the suppression of the Democracy Movement, officials in the Chinese government made a correlation between the political control of students and the maintenance of political power by the Chinese Communist Party. The political repression of students in China resulted in new educational policies that changed the way that universities functioned and the way that students were allowed to interact. Political repression efforts directed at the large population of overseas Chinese students in the United States prompted governmental action to extend legal protection to these students. The long term implications of this repression are evident in the changed student culture among Chinese students and the extensive number of overseas students who did not return to China. -

Rough Justice in Beijing: Punishing the "Black Hands" of Tiananmen Square

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title Rough Justice in Beijing: Punishing the "Black Hands" of Tiananmen Square Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7zz8w3wg Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 10(1) Author Munro, Robin Publication Date 1991 DOI 10.5070/P8101021984 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ROUGH JUSTICE IN BEIJING* Punishing the "Black Hands" of Tiananmen Square Robin Munro** 1. INTRODUCTION During late spring and early summer, namely, from mid-April to early June of 1989, a tiny handful of people exploited student unrest to launch a planned, organized and premeditated political turmoil, which later developed into a counterrevolutionary rebel- lion in Beijing, the capital. Their purpose was to overthrow the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and subvert the so- cialist People's Republic of China.... In order to achieve thorough victory, we should mobilize the people completely, strengthen the people's democratic dictator- ship and spare no effort to ferret out the counterrevolutionary rioters. We should uncover instigators and rebellious conspira- tors, punish the organizers and schemers of the unrest and the counterrevolutionary rebellion ...and focus the crackdown on a handful of principal culprits and diehards who refuse to repent.' (Chen Xitong, Mayor of Beijing, on June 30, 1989.) In late 1990, the Chinese government brought formal charges against several dozen of the most prominent leaders of the May- June 1989 Tiananmen Square pro-democracy movement. Trials held in the first two months of 1991 have resulted in sentences rang- ing from two to thirteen years for students and intellectuals. -

Nameless Art in the Mao Era

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2017 Nameless Art in the Mao Era Tianchu Gao College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, and the Modern Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Gao, Tianchu, "Nameless Art in the Mao Era" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1091. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1091 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nameless Art in the Mao Era A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Department of Art and Art History from The College of William and Mary by Tianchu (Jane) Gao 高天楚 Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, Non-Honors) ________________________________________ Xin Wu, Director ________________________________________ Sibel Zandi-Sayek ________________________________________ Charles Palermo ________________________________________ Michael Gibbs Hill Williamsburg, VA May 2, 2017 ABSTRACT This research project focuses on the first generation of No Name (wuming 無名), an underground art group in the Cultural Revolution which secretly practiced art countering the official Socialist Realism because of its non-realist visual language and art-for-art’s-sake philosophy. These artists took advantage of their worker status to learn and practice art legitimately in the Mass Art System of the time. They developed their particular style and vision of art from their amateur art training, forbidden visual and textual sources in the underground cultural sphere, and official theoretical debates on art. -

Atheist Political Activists Turned Protestants: Religious Conversion Within China’S Dissident Community

Atheist Political Activists Turned Protestants: Religious Conversion within China’s Dissident Community by Teresa Wright Professor and Chair Department of Political Science California State University, Long Beach Long Beach, CA 90840 [email protected] and Teresa Zimmerman-Liu M.A. Candidate Department of Asian/Asian-American Studies California State University, Long Beach Long Beach, CA 90840 [email protected] Prepared for delivery at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the International Studies Association San Diego, April 1-4, 2012 *Please do not cite or quote without the authors’ permission Atheist Political Activists Turned Protestants: Religious Conversion within China’s Dissident Community Two related questions most compel China scholars and observers today: (i) why, despite dramatic economic liberalization and growth, has China not democratized? and (ii) will China democratize in the future? While some existing studies are more optimistic than others, most focus on the adaptability of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as the key to its longevity.1 What is missing from this literature is a detailed scholarly examination of what has happened to the pro-democracy activists who led the political protests that arose in China in the 1980s, which culminated in the massive demonstrations of 1989. One particularly interesting development is that a large number of these political activists have, in the post-1989 period, become Protestant Christians. Moreover, this development has coincided with a larger explosion of Christianity in the post-Mao era. There are an estimated 50 to 100 million Protestants in China today—a sizeable portion of the population, and indeed one that rivals the (roughly 80 million) membership of the CCP.2 The expansion of Christianity in contemporary China has spurred a small but quickly growing body of scholarly studies. -

Volume I. Documents

International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ INVENTORY OF THE COLLECTION CHINESE PEOPLE'S MOVEMENT, SPRING 1989 VOLUME I: DOCUMENTS at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ For a list of the Working Papers published by Stichting beheer IISG, see page 123. International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ Frank N. Pieke and Fons Lamboo INVENTORY OF THE COLLECTION CHINESE PEOPLE'S MOVEMENT, SPRING 1989 VOLUME I: DOCUMENTS at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) Stichting Beheer IISG Amsterdam, August 1990 International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ CIP-GEGEVENS KONINLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Pieke, Frank N. Inventory of the Collection Chinese People's Movement, spring 1989 / Frank N. Pieke and Fons Lamboo. - Amsterdam: Stichting beheer IISG Vol. I: Documents at the International Institute of Social History (IISH). - (IISG-working papers, ISSN 0921-4585 ; 14) Met reg. ISBN 90-6861-057-0 SISO az-chin 942 UDC 323.26(510)"1989"(083.82) NUGI 641 Trefw.: Chinese volksbeweging (collectie) ; IISG ; catalogi. c 1990 Stichting beheer IISG All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar worden gemaakt door middel van druk, fotocopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. Printed in the Netherlands International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents v Preface vi 1. -

Tiananmen's Most Wanted

TIANANMEN’S 2004 .2, MOST WANTED—WHERE ARE NO THEY NOW? FORUM RIGHTS COMPILED BY STACY MOSHER CHINA On June 13, the Beijing Public Security Bureau issued a list of 21 leaders of the 1989 protest 49 movement who were being sought for arrest. Following is the list, and what has become of those people since. DEBT THE ACTIVIST THEN NOW Wang Dan A history student at Peking University, and an On April 18, 1998,Wang was freed on medical organizer of the Beijing Students Autonomous parole and sent into exile to the United States. He is HONORING Federation,Wang was arrested on July 2, 1989 and now completing his Ph.D. studies in history at Y: on January 26, 1991 was sentenced to 4 years in Harvard University. He is an honorary member of prison on charges of counterrevolutionary propa- HRIC’s board of directors ganda and incitement. Released on parole on MEMOR February 17, 1993,Wang was detained again on May 21, 1995 after participating in petitions calling for release of all prisoners arrested in connection with June 4th. On October 30, 1996 he was sentenced to 11 years in prison for subversion. Wuer Kaixi A Uighur student leader from Beijing Normal Univer- Wuer Kaixi studied at Harvard, then at Dominican sity,Wuer Kaixi evaded arrest and escaped to the West College in San Rafael, California, before moving to by way of Hong Kong. Taiwan, where he is now the host of a radio talk show. Liu Gang A graduate in physics at Peking University, Liu worked Following his release in 1995, Liu fled China via at The Beijing Social and Economic Sciences Research Hong Kong in May 1996, saying that he and his fam- Institute in late 1988, and was a close associate of ily had been subjected to official harrassment.After Fang Lizhi. -

“China” on Display for European Audiences? the Making of an Early Travelling Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art–China Avantgarde (Berlin/1993)

66 “China” on Display for European Audiences? “China” on Display for European Audiences? The Making of an Early Travelling Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art–China Avantgarde (Berlin/1993) Franziska Koch, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Contemporary Chinese Art–Phenomenon and Discursive Category Mediated by Exhibitions Exhibitions have always been at the heart of the modern art world and its latest developments. They are contested sites where the joint forces of art objects, their social agents, and institutional spaces intersect temporarily and provide a visual arrangement for specific audiences, whose interpretations themselves feed back into the discourse on art. Viewed from this perspective, contemporary Chinese art–as a phenomenon and as a discursive category that refer to specific dimensions of artistic production in post-1979 China– was mediated through various exhibitions that took place in the People’s Republic of China (hereafter, People’s Republic). In 1989, art from the People’s Republic also began to appear in European and North American exhibitions significantly expanding Western knowledge of this artistic production. Since then, national and international exhibitions have multiplied, while simultaneously becoming increasingly entangled: the sheer number of artworks that circulate between Chinese urban art scenes and Western art metropolises has risen steeply, as have the often overlapping circles of contemporary artists, art critics, art historians, gallery owners, and collectors who successfully engage across both sides of the field. To a certain degree these agents govern exhibition-making and act as important mediators or “cultural brokers”1 globalizing the discursive category of contemporary 1 For a recent study that explores the notion of the “cultural broker” from a transcultural perspective see Rudolf G.