ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG ORAL HISTORY PROJECT The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Map of Healing Garden Artwork

Mark Ackerman • Nicolas Africano • Yaacov Agam • Jonathan Agger • Anni Albers • Josef Albers • Lita Albuquerque • Pierre Alechinsky • Peter Alexander • Elray Alkristy • Otmar Alt • John Altoon • Amos Amit • Othello Anderson • Michael Ansell • Karel Appel • Shusaku Arakawa • Cynthia Archer • Ardison Phillips • Jim Arkatov • Arman • Robert Arneson • Charles Arnoldi • Lisa Aronzon • Fred Arundel • Tadashi Asoma • Chet Atkins • Mario Avanti • Judith Azur • Olle Baertling • Claude Baillargeon • Richard Baker • Micha Bar-Am • Lynda Barckert • Lionel Barrymore • Frank Barsotti • Frank Beatty • David Marc Belkin • Gerald Belkin • Larry Bell • Mark Bellog • Lynda Benglis • Billy Al Bengston • Fletcher Benton • Dimitrie Berea • Don Berger • Joseph Bergler, The Younger • Elizabeth V. Blackadder • Lucienne Bloch • Karl Blossfeldt • Howard Bond • John Robert Borgstahl • Jonathan Borofsky • Richard Bosman • Paul Brach • Matthew Brady • Charles Bragg • Warren Brandt • Bettina Brendel • Ernest Briggs • Charlie Brown • Christopher Brown • James Paul Brown • Jerry Burchman • Hans Burkhardt • Bob Burley • Sakti Burman • Jerry Byrd • Alexander Calder • Jo Ann Callis • Tom Carr • Stuart Caswell • Marc Chagall • Judy Chicago • Christo • Clutie • Jodi Cobb • Jean Cocteau • Bruce Cohen • Larry Cohen • Chuck Connelly ARTIST • Greg / WORKConstantine • Ron Cooper • Greg Copeland • Amy Cordova • Sam Coronado • Steven Cortright • Robert Cottingham • Arnold Crane • Barbara Crane • Jeff Crisman • Chris Cross • Yvonne Cross • Ford Crull • Woody Crumbo • William Crutchfield -

National Gallery of Art News Release

* ** ** National Gallery of Art News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Tina Coplan July 8, 1991 Liz Kimball (202) 842-6353 INNOVATIVE ART FROM GRAPHICSTUDIO AT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART. SEPTEMBER 15 WASHINGTON, D.C. A survey of more than ninety prints and edition sculptures produced during the last two decades at Graphicstudio by some of America's foremost contemporary artists will be presented September 15, 1991, through January 5, 1992, in the West Building of the National Gallery of Art. Graphicstudio, founded in 1968 by artist Donald Saff at the University of South Florida, Tampa, has become one of the leading workshops in the United States engaged in unique research in the production of fine art editions. Graphicstudio; Contemporary Art from the Collaborative Workshop at the University of South Florida will feature a diverse selection of subjects, styles, and media, produced by twenty-four artists working with Graphicstudio's versatile staff. In addition to the completed works, the show will include a selection of working drawings and other preparatory materials never before exhibited. "This exhibition, drawn from the Graphicstudio Archive which was established at the National Gallery in 1986, includes extraordinary prints and edition sculptures produced with a great deal of imagination, innovation, and technical complexity by some of America's most talented artists," said J. Carter Brown, director of the National Gallery of Art. -more- fourth Street in Constitution Avenue NW Washington DC 20565 (202) 842 6353 Facsimile (202) 289 5446 graphicstudio . page 2 "The Graphicstudio exhibition at the National Gallery is the ultimate recognition of our mission at the University of South Florida, which is to create new knowledge through art," said Alan Eaker, director of Graphicstudio. -

Download Exhibition Catalogue

LIGHT / SPACE / CODE Opposite: Morris Louis, Number 2-07, 1961 (detail) Light / Space / Code How Real and Virtual Systems Intersect The Light and Space movement (originated in the 1960s) coincided with the Visual art and the natural sciences have long produced fruitful collaborations. development of digital technology and modern computer programming, and in Even Isaac Newton’s invention of the color wheel (of visible light spectra) has recent years artists have adapted hi-tech processes in greater pursuit of altering aided visual artists immensely. Artists and scientists share a likeminded inquiry: a viewer’s perception using subtle or profound shifts in color, scale, luminosity how we see. Today’s art answers that question in tandem with the expanded and spatial illusion. scientific fields of computer engineering, cybernetics, digital imaging, information processing and photonics. Light / Space / Code reveals the evolution of Light and Space art in the context of emerging technologies over the past half century. The exhibit begins by iden- — Jason Foumberg, Thoma Foundation curator tifying pre-digital methods of systems-style thinking in the work of geometric and Op painters, when radiant pigments and hypnotic compositions inferred the pow- er of light. Then, light sculpture introduces the medium of light as an expression of electronic tools. Finally, software-generated visualizations highlight advanced work in spatial imaging and cyberspace animation. Several kinetic and inter- active works extend the reach of art into the real space of viewer participation. A key sub-plot of Light / Space / Code concerns the natural world and its ecol- ogy. Since the Light and Space movement is an outgrowth of a larger environ- mental art movement (i.e., Earthworks), and its materials are directly drawn from natural phenomena, Light and Space artists address the contemporary conditions of organisms and their habitation systems on this planet. -

UNIVERSITY of SOUTH FLORIDA Honorary Degree Recipients

University of South Florida Scholar Commons USF St. Petersburg campus Graduations and USF St. Petersburg campus Convocations, Commencements Graduations, and Celebrations 1-1-2006 USF Honorary Degree Recipients at Commencements through May 2006 University of South Florida. System. University of South Florida. Office of the esident.Pr Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/graduations_commencements Scholar Commons Citation University of South Florida. System. and University of South Florida. Office of the esident.,Pr "USF Honorary Degree Recipients at Commencements through May 2006" (2006). USF St. Petersburg campus Graduations and Commencements. 40. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/graduations_commencements/40 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the USF St. Petersburg campus Convocations, Graduations, and Celebrations at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in USF St. Petersburg campus Graduations and Commencements by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA Honorary Degree Recipients DATE DEGREE RECIPIENT 9/26/60 Doctor of Science George R. Cooley (Deceased) (Businessman, research botanist, Harvard & USF) 11/9/69 Doctor of Laws Sam M. Gibbons (U .S. House of Representatives) 101 E. Kennedy Blvd., #1425 Tampa, FL 33602 11/9/69 Doctor of Laws David M. Delo (Former President, Univ. of Tampa) 10900 Temple Terrace Seminole, FL 34642 11/9/69 Doctor of Laws Michael Bennett (Former President, SPJC) Address Unknown 6/14/70 Doctor of Laws Edith Green (Former Member, U.S. House of Representatives) Address Unknown 6/13/71 Doctor of Humane Letters John S. Allen (Deceased) 1st USF President 10/31/71 Doctor of Humane Letters Harris W. -

9A17 55542 199110.Pdf

OCTOBER On/The Modern Portrait and Chuck 1:00 Gallery Talk: The Societal Eye of 25 FRIDAY Close the Eighteenth Century' 10:30, 12:30, 1:30 Film: Masters of 1:00 Gallery Talk: Graphicstudio 1:30 Film: Masters of Illusion Illusion 2:30 Films: A Young Man's Dream 2:30 Film: The Giant Woman and the See bottom panels for introductory 11:00 Lecture: Circa 1492 and a Woman's Secret and A Day on Lightning Man and foreign language tours; see 12:00 Gallery Talk: The Societal Eye the Grand Canal with the Emperor of 2:30 Gallery Talk: Boston Painters, reverse side for complete film of the Eighteenth Century China Boston Ladies information. 26 SATURDAY 6 SUNDAY 13 SUNDAY 10:15 Survey Course: The Ancient 1 TUESDAY 12:00 Gallery Talk: Graphicstudio 11:30, 1:30 Film: Masters of Illusion World: Early Christian, Byzantine 12:00 Gallery Talk: Costume in 1:00 Films: Chuck Close: Head- 12:00 Gallery Talk: The Societal Eye and Islamic Art Renaissance and Baroque Art On/The Modern Portrait and Chuck of the Eighteenth Century 12:00, 1:30 Film: Masters of Illusion Close 1:00 Film: Roy Lichtenstein Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Pope Pius I'll in the Sisline Chapel (detail),dated 1810. 1:00 Gallery Talk: Graphicstudio 2 WEDNESDAY 4:00 Sunday Lecture: Conversations 4:00 Sunday Lecture: Circa 1492: National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection 12:00 Gallery Talk: Rembrandt's with Artists, VIII, Nancy Graves History and Art 7:00 Concert: Krosnick/Kalish Duo, 27 SUNDAY Film: The World of Gilbert and Lucretias 6:00 Films: Seni's Children and Kings 6:00 18 FRIDAY cello and piano 11:30, 1:30 Film: Masters of Illusion 12:30 Films: Chuck Close: Head- of the Water George 10:30, 1:30 Film: Masters of Illusion 12:00 Gallery Talk: Graphicstudio On/The Modern Portrait and Chuck 7:00 Concert: National Gallery 7:00 Concert: National Gallery Vocal 11:00 Lecture: Circa 1492 21 MONDAY 2:00 Lecture: Circa 1492 early music 12:00 Gallery Talk: Graphicstudio Close Orchestra. -

The Role and the Nature of Repetition in Jasper Johns's Paintings in The

The Role and the Nature of Repetition in Jasper Johns’s Paintings in the Context of Postwar American Art by Ela Krieger A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History Approved Dissertation Committee Prof. Dr. Isabel Wünsche Jacobs University Bremen Prof. Dr. Paul Crowther Alma Mater Europaea Ljubljana Dr. Julia Timpe Jacobs University Bremen Date of Defense: 5 June 2019 Social Sciences and Humanities Abstract Abstract From the beginning of his artistic career, American artist Jasper Johns (b. 1930) has used various repetitive means in his paintings. Their significance in his work has not been sufficiently discussed; hence this thesis is an exploration of the role and the nature of repetition in Johns’s paintings, which is essential to better understand his artistic production. Following a thorough review of his paintings, it is possible to broadly classify his use of repetition into three types: repeating images and gestures, using the logic of printing, and quoting and returning to past artists. I examine each of these in relation to three major art theory elements: abstraction, autonomy, and originality. When Johns repeats images and gestures, he also reconsiders abstraction in painting; using the logic of printing enables him to follow the logic of another medium and to challenge the autonomy of painting; by quoting other artists, Johns is reexamining originality in painting. These types of repetition are distinct in their features but complementary in their mission to expand the boundaries of painting. The proposed classification system enables a better understanding of the role and the nature of repetition in the specific case of Johns’s paintings, and it enriches our understanding of the use of repetition and its perception in art in general. -

Kristine Stiles

Concerning Consequences STUDIES IN ART, DESTRUCTION, AND TRAUMA Kristine Stiles The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London KRISTINE STILES is the France Family Professor of Art, Art Flistory, and Visual Studies at Duke University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2016 by Kristine Stiles All rights reserved. Published 2016. Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 12345 ISBN13: 9780226774510 (cloth) ISBN13: 9780226774534 (paper) ISBN13: 9780226304403 (ebook) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226304403.001.0001 Library of Congress CataloguinginPublication Data Stiles, Kristine, author. Concerning consequences : studies in art, destruction, and trauma / Kristine Stiles, pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9780226774510 (cloth : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226774534 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226304403 (ebook) 1. Art, Modern — 20th century. 2. Psychic trauma in art. 3. Violence in art. I. Title. N6490.S767 2016 709.04'075 —dc23 2015025618 © This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper). In conversation with Susan Swenson, Kim Jones explained that the drawing on the cover of this book depicts directional forces in "an Xman, dotman war game." The rectangles represent tanks and fortresses, and the lines are for tank movement, combat, and containment: "They're symbols. They're erased to show movement. 111 draw a tank, or I'll draw an X, and erase it, then redraw it in a different posmon... -

Arcadian Retreat)

Catastrophe (Arcadian Retreat) By Roni Feinstein, July 2013 Part of the Rauschenberg Research Project Cite as: Roni Feinstein, “Catastrophe (Arcadian Retreat),” Rauschenberg Research Project, July 2013. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, http://www.sfmoma.org/ artwork/97.827/essay/catastrophe-arcadian-retreat/. 1 In the Arcadian Retreat series, of which Catastrophe (Arcadian Retreat) (1996) is a part, Robert Rauschenberg combined images of the ancient and modern worlds in paintings that blend antiquated techniques of picture making such as fresco painting with the state-of-the-art technologies of digital printing. These majestic and physically weighty works exemplify his ongoing efforts to navigate uncharted creative territory and experiment with previously unexplored processes and materials. As this essay will demonstrate, both impulses were intimately connected with Rauschenberg’s artistic and personal history. 2 From 1962 until the early 1990s, the silkscreen process was the means by which Rauschenberg transferred photographic images onto his large-scale canvases. This method involved the use of commercially prepared screens imprinted with images he had found in mass-media sources. Over the course of three decades the artist created dozens of series in which he combined silkscreened images on any number of surfaces, among them canvas, paper, fabric, and a range of metals, including copper, brass, bronze, and aluminum.1 Sometime in 1991 Rauschenberg became aware of large-format color inkjet printers, which employ continuous, high-pressure sprays of ink to push pigment deeply into the paper, producing even, dot-free color prints.2 He quickly began 1. Robert Rauschenberg, Catastrophe (Arcadian Retreat), 1996; inkjet transfer and wax on fresco to explore the digital print’s rich potential as a means of incorporating photographic panels, 111 x 75 in. -

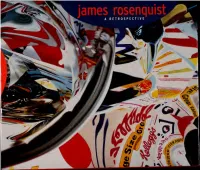

James Rosenquist : a Retrospective

james rosenquist A RETROSPECTIVE ^ ;;• >u james rosenquist A RETROSPECTIVE WALTER HOPPS and SARAH BANCROFT Since the late 19505, lames Rosenquist has created in exception il and consistently intriguing bod) of work. A leader of the American Pop art movement in the 1960s, alone with such contemporaries as Jim Dine. Ro> Lichtenstein. Claes Oldenburg, and Andy Warhol. Rosenquist drew on the popular iconography of advertising and mass media to conjure a sense of contemporary life and the political tenor of the times. Born and raised in the Midwest and working in New Yoik and Florida, he has developed a distinctK American voice—\ei his work comments on popular culture and institutions from a continually evolving global perspective. From his early days as a billboard painter to his recent masterful use of abstract painting techniques, Rosenquist has maintained a passion for visually, color, line and shape that con- tinues to dazzle viewers and influence younger generations of artists. Published on the occasion of a Comprehensive retrospective organized by Walter Hopps and Sarah Bancroft, this monograph is a definitive investigation of Rosenquist's more than forty-year career in painting and sculpture, source collages, draw ingE and jraphics and multiples, from his earliest works to the present. Lavishly illustxansd, the book features nearly three hundred of ii most in meant works, including several that have never been published and a broad selection of source collages. The essay by Hopps pro\ id en iew of Rosenquist's career, and those b> |ulia Blaut and Ruth E. Fine- reveal his working processes in collage and printmakin ely. -

2011 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION Diana Bracco BOARD of TRUSTEES COMMITTEE W

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART 2011 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION Diana Bracco BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE W. Russell G. Byers Jr. (as of 30 September 2011) Victoria P. Sant Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Robert W. Duemling Frederick W. Beinecke Barney A. Ebsworth Mitchell P. Rales Gregory W. Fazakerley Sharon P. Rockefeller Doris Fisher John Wilmerding Aaron I. Fleischman Juliet C. Folger FINANCE COMMITTEE Marina K. French Mitchell P. Rales Lenore Greenberg Chairman Rose Ellen Greene Timothy F. Geithner Richard C. Hedreen Secretary of the Treasury Helen Henderson Frederick W. Beinecke John Wilmerding Victoria P. Sant Benjamin R. Jacobs Chairman President Sharon P. Rockefeller Sheila C. Johnson Victoria P. Sant Betsy K. Karel John Wilmerding Linda H. Kaufman Mark J. Kington AUDIT COMMITTEE Robert L. Kirk Frederick W. Beinecke Jo Carole Lauder Chairman Leonard A. Lauder Timothy F. Geithner Secretary of the Treasury LaSalle D. Leffall Jr. Mitchell P. Rales Robert B. Menschel Harvey S. Shipley Miller Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Mitchell P. Rales Victoria P. Sant Diane A. Nixon John Wilmerding John G. Pappajohn Sally E. Pingree TRUSTEES EMERITI Diana C. Prince Roger W. Sant Robert F. Erburu B. Francis Saul II John C. Fontaine Thomas A. Saunders III Julian Ganz, Jr. Fern M. Schad Alexander M. Laughlin Albert H. Small David O. Maxwell Michelle Smith Ruth Carter Stevenson Benjamin F. Stapleton Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Roberts Jr. Luther M. Stovall Chief Justice of the EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Ladislaus von Hoffmann United States Victoria P. Sant President Alice L. Walton William L. -

June 1979 CAA Newsletter

newsletter Volume 4, Number 2 June 1979 1980 annual meeting: call for papers and panelists The 1980 CAA annual meeting will be held in New Orleans, the interpretation or the transmission of architectural, painting' or Wednesday, January 3D-Saturday, February 2. The Hyatt Regency sculpture programs in the Romanesque period. will serve as headquarters hotel. Art history sessions have been planned by Caecilia Davis-Weyer, London, Paris, Rome, Avignon, Prague: 1200-1350. Eleanor Newcomb College, Tulane University. Studio sessions have been Greenhill, Dept. of Art, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Tex. planned by Lin Emery, sculptor, New Orleans. Listed below are the 78712. topics they have selected, Those wishing to participate in any session The session is designed to explore international or inter-regional should write to the chairman of that session before October I, 1979. exchanges in art, architecture or urban planning particularly as the Reminder: In accordance with the Annual Meeting Program result of the movement of artists and patrons among the great centers Guidelines, no one may participate in more than one session. While or royal and papal power. Papers on monastic or communal projects it is perfectly good form to submit more than one paper or even to are also welcome if such projects can be shown to result from the submit the same paper to more than one chairman, it would avoid same international movement. considerable last-minute hassles if both chairmen were forewarned. In a further attempt to introduce new and different faces, session Art and Liturgy. L.D. Ettlinger, University of California, chairmen are encouraged not to accept a paper by anyone who has Berkeley. -

Deli Sacilotto

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG ORAL HISTORY PROJECT The Reminiscences of Deli Sacilotto Columbia Center for Oral History Research Columbia University 2015 PREFACE The following oral history is the result of a recorded interview with Deli Sacilotto conducted by Cameron Vanderscoff on July 24, 2015. This interview is part of the Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project. The reader is asked to bear in mind that s/he is reading a transcript of the spoken word, rather than written prose. Transcription: Audio Transcription Center Session #1 Interviewee: Deli Sacilotto Location: Boca Raton, Florida Interviewer: Cameron Vanderscoff Date: July 24, 2015 Q: Okay, so today is Friday, July 24, 2015 and this is Cameron Vanderscoff here with Deli Sacilotto in his residence in Boca Raton. Sacilotto: Yes. Q: I’ve heard it pronounced several different ways since I’ve been here. Sacilotto: Boca Raton, in the mouth of the rat. [Laughter] Q: We’re here for the Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project to talk about your print collaborations with Rauschenberg in a couple of different contexts. But first I’d like to know a little bit about you. So if you could just state for the record when and where you were born and connect some dots about how you got into printmaking. I’m curious about how you came to this point where you collaborated with Rauschenberg and sort of walking through the steps of your own early interest in printmaking, your background. Sacilotto – 1 – 2 Sacilotto: Yes. My interest in art goes back to the time when I went to the Alberta College of Art [and Design, Canada].