Atheist Political Activists Turned Protestants: Religious Conversion Within China’S Dissident Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

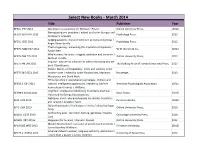

Select New Books - March 2014 Title Publisher Year BF321 .P67 2012 Attention in a Social World / Michael I

Select New Books - March 2014 Title Publisher Year BF321 .P67 2012 Attention in a social world / Michael I. Posner. Oxford University Press, c2012. Stereotyping and prejudice / edited by Charles Stangor and BF323.S63 S747 2013 Psychology Press, 2013. Christian S. Crandall. Judging passions : moral emotions in persons and groups / BF531 .G56 2012 Psychology Press, 2012. Roger Giner-Sorolla. That's disgusting : unraveling the mysteries of repulsion / BF575.A886 H47 2012 W.W. Norton & Co., c2012. Rachel Herz. Why humans like to cry : tragedy, evolution and the brain / BF575.C88 T75 2012 Oxford University Press, 2012. Michael Trimble. Impulse : why we do what we do without knowing why we BF575.I46 L49 2013 The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013. do it / David Lewis. Shame, blame, and culpability : crime and violence in the BF575.S45 S522 2013 modern state / edited by Judith Rowbotham, Marianna Routledge, 2013. Muravyeva, and David Nash. Ethical practice in operational psychology : military and BF636.3 .E84 2011 national intelligence applications / edited by Carrie H. American Psychological Association, c2011. Kennedy and Thomas J. Williams. Ungifted : intelligence redefined / Scott Barry Kaufman ; BF698.9.I6 K38 2013 Basic Books, [2013] illustrated by George Doutsiopoulos. Righteous mind : why good people are divided by politics BJ45 .H25 2012 Pantheon Books, c2012. and religion / Jonathan Haidt. Oxford handbook of the history of ethics / edited by Roger BJ71 .O94 2013 Oxford University Press, 2013. Crisp. Confronting evils : terrorism, torture, genocide / Claudia BJ1401 .C293 2010 Cambridge University Press, 2010. Card. BJ1481 .R87 2012x Happiness for humans / Daniel C. Russell. Oxford University Press, 2012. Muslim Brotherhood : evolution of an Islamist movement / BP10.I385 W53 2013 Princeton University, [2013] Carrie Rosefsky Wickham. -

Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989

Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989 Geremie Barmé1 There should be room for my extremism; I certainly don’t demand of others that they be like me... I’m pessimistic about mankind in general, but my pessimism does not allow for escape. Even though I might be faced with nothing but a series of tragedies, I will still struggle, still show my opposition. This is why I like Nietzsche and dislike Schopenhauer. Liu Xiaobo, November 19882 I FROM 1988 to early 1989, it was a common sentiment in Beijing that China was in crisis. Economic reform was faltering due to the lack of a coherent program of change or a unified approach to reforms among Chinese leaders and ambitious plans to free prices resulted in widespread panic over inflation; the question of political succession to Deng Xiaoping had taken alarming precedence once more as it became clear that Zhao Ziyang was under attack; nepotism was rife within the Party and corporate economy; egregious corruption and inflation added to dissatisfaction with educational policies and the feeling of hopelessness among intellectuals and university students who had profited little from the reforms; and the general state of cultural malaise and social ills combined to create a sense of impending doom. On top of this, the government seemed unwilling or incapable of attempting to find any new solutions to these problems. It enlisted once more the aid of propaganda, empty slogans, and rhetoric to stave off the mounting crisis. University students in Beijing appeared to be particularly heavy casualties of the general malaise. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Christian House Church Members by the Public

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 1 of 8 Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Home > Research Program > Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests (RIR) respond to focused Requests for Information that are submitted to the Research Directorate in the course of the refugee protection determination process. The database contains a seven- year archive of English and French RIRs. Earlier RIRs may be found on the UNHCR's Refworld website. Please note that some RIRs have attachments which are not electronically accessible. To obtain a PDF copy of an RIR attachment please email [email protected]. 10 October 2014 CHN104966.E China: Treatment of "ordinary" Christian house church members by the Public Security Bureau (PSB), including treatment of children of house church members (2009-2014) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa 1. House Church Demography According to the Bertelsmann Stiftung Transformation Index (BTI), which analyzes the quality of democracy and political management in 128 countries (Bertelsmann Stiftung n.d.), there are an estimated 80 million Christians in China, "many of whom congregate in illegal house churches" (ibid. 2014, 5). The Wall Street Journal reports that house church members could number between 30 and 60 million (29 July 2011). Voice of America (VOA) notes that the exact number of Christians is difficult to estimate because many worship at underground house churches (VOA 16 June 2014). For detailed information on the estimated number of registered and unregistered Christians in China, by denomination, as of 2012, see Response to Information Request CHN104189. -

Standoff at Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: the Making of Goddess of Democracy

2019/4/23 Standoff At Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy 更多 创建博客 登录 Standoff At Tiananmen How Chinese Students Shocked the World with a Magnificent Movement for Democracy and Liberty that Ended in the Tragic Tiananmen Massacre in 1989. Relive the history with this blog and my book, "Standoff at Tiananmen", a narrative history of the movement. Home Days People Documents Pictures Books Recollections Memorials Monday, May 30, 2011 "Standoff at Tiananmen" English Language Edition Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy Click on the image to buy at Amazon "Standoff at Tiananmen" Chinese Language Edition On May 30, 1989, the statue Goddess of Democracy was erected at Tiananmen Square and became one of the lasting symbols of the 1989 student movement. The following is a re-telling of the making of that statue, originally published in the book Children of Dragon, by a sculptor named Cao Xinyuan: Nothing excites a sculptor as much as seeing a work of her own creation take shape. But although I was watching the creation of a sculpture that I had had no part in making, I nevertheless felt the same excitement. It was the "Goddess of Democracy" statue that stood for five days in Tiananmen Square. Until last year I was a graduate student at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, where the sculpture was made. I was living there when these events took place. 点击图像去Amazon购买 Students and faculty of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, which is located only a short distance from Tiananmen Square, had from the beginning been actively involved in the demonstrations. -

Resource List

Resource List rative activities relating to June 4th. The Nomination of the Tiananmen Mothers for Web site contains information about ongo- the Nobel Peace Prize 2004 The 1989 ing and upcoming campaigns and rallies in http://209.120.234.77/64/press/ .2, Democracy Movement Hong Kong and overseas. It also provides TiananmenMothersPackage_2004_Final.pdf NO links to many other relevant Web sites. English COMPILED BY STACY MOSHER This packet of materials was prepared by Independent Federation of Chinese Stu- the Independent Federation of Chinese Stu- dents and Scholars dents and Scholars to support their nomi- WEB SITES: www.ifcss.net nation of the Tiananmen Mothers for the FORUM Chinese and English 2004 Nobel Peace Prize. 64 Memo The IFCSS was founded in Chicago in Princeton Professor Perry Link’s letter of http://www.64memo.org/index.asp August 1989 by more than 1,000 Chinese nomination can be read in Chinese at: RIGHTS Chinese student representatives from more than http://www.dajiyuan.com/gb/4/4/2/n499 Operated by Tiananmen veteran Feng 200 U.S. universities, and remains the 469.htm CHINA Congde and sponsored by HRIC, this Web most influential overseas Chinese student The text was transcribed from Link’s site provides an archive of documents, arti- group. Although less active in recent years, broadcast of the letter on Radio Free Asia. 79 cles and images relating to June 4th. IFCSS is organizing the collection of arti- cles, documents and photos relating to its Tiananmen Square, 1989: The Declassi- Boxun.com Tiananmen Feature upcoming 15th anniversary. fied History http://www.boxun.com/my-cgi/post/ http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/N TURES display_all.cgi?cat=64 June 4th Essays SAEBB16/ FEA Chinese http://www.dajiyuan.com/gb/nf2976.htm English Boxun’s special section of photos, articles Chinese An archive of official documents of the U.S. -

Amnesty International

amnesty international PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA No Improvement in Human Rights: The Imprisonment of dissidents in 1998 4 March 1999 AI Index: ASA 17/14/99 Despite the marking of the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights in 1998 and despite the recent signing by China of the two United Nations Covenants on Human Rights there are still no guarantees for the Chinese people that they will not be detained or arrested for seeking the freedoms of association and expression enshrined in the UN Declaration. In the past twelve months, many scores of people throughout China have been detained, harassed and imprisoned solely for exercising these rights. The Chinese government’s signing of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in October 1998, the visits to China of American President Bill Clinton, and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Mary Robinson were heralded as triumphs for diplomacy and human rights ‘dialogue’. International opinion began to suggest that the Chinese authorities were making improvements in human rights. However, as the prospect of international censure recedes and the international spotlight faded, the Chinese authorities once again began to crack down on dissidents and activists. During the last few weeks of 1998, over 29 dissidents were detained, four leading dissidents sentenced to lengthy terms of imprisonment and several other dissidents and labour activists have been sentenced to re-education through labour terms and lengthy terms of imprisonment. Since October 1998 when China signed the ICCPR it is estimated that over 80 dissidents have been detained and at least 15 high profile dissidents have been given heavy prison sentences or assigned to re-education through labour. -

Tragic Anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Protests and Massacre

TRAGIC ANNIVERSARY OF THE 1989 TIANANMEN SQUARE PROTESTS AND MASSACRE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 3, 2013 Serial No. 113–69 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 81–341PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:13 Nov 03, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_AGH\060313\81341 HFA PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DANA ROHRABACHER, California Samoa STEVE CHABOT, Ohio BRAD SHERMAN, California JOE WILSON, South Carolina GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey TED POE, Texas GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MATT SALMON, Arizona THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BRIAN HIGGINS, New York JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts MO BROOKS, Alabama DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island TOM COTTON, Arkansas ALAN GRAYSON, Florida PAUL COOK, California JUAN VARGAS, California GEORGE HOLDING, North Carolina BRADLEY S. -

Han Dongfang: from Tiananmen Hero to Modest Workers' Champion

48 autumn-winter 2014/HesaMag #10 Books 1/2 Han Dongfang: from Tiananmen hero to modest workers’ champion Don’t, whatever you do, call him a dissident. commenting on working conditions in China But there is still a long and challenging Hero of Tiananmen Square he may be, but he from his cramped studio. But he got bored road ahead. Industrial development has put won’t be labelled that way – too intellectual, with it not being connected to workface real- the environment and workers’ health at risk. too highbrow. Han Dongfang always remem- ities. "I was just an editorializing journalist, "Most of the cases we have taken up in the bers that before the spring 1989 protests he never getting out of the office and doing noth- past two years concern work-related accidents was a railway worker. And who with a name ing but commenting," he now says. and diseases," he says. Silicosis is wreaking like Dongfang – meaning "the East" in refer- So he persuaded Radio Free Asia to set havoc, affecting more than six million work- ence to The East is Red, China’s anthem dur- up a direct chat line with workers in all re- ers – miners, naturally, but also workers in ing the Cultural Revolution – could set them- gions of China. "These weekly talks helped the building trades, cement works, jewellery selves up as a counter-revolutionary? me understand how Chinese workers live manufacture, etc. To help them claim com- No, Han Dongfang was never a self-ap- and what they go through every day. They let pensation, the China Labour Bulletin sends pointed Lech Walesa of the Far East. -

Testimony of Zhou Fengsuo, President Humanitarian China and Student Leader of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Demonstrations

Testimony of Zhou Fengsuo, President Humanitarian China and student leader of the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations Congressman McGovern, Senator Rubio, Members of Congress, thank you for inviting me to speak in this special moment on the 30th anniversary of Tiananmen Massacre. As a participant of the 1989 Democracy Movement and a survivor of the Massacre started in the evening of June 3rd, it is both my honor and duty to speak, for these who sacrificed their lives for the freedom and democracy of China, for the movement that ignited the hope of change that was so close, and for the last 30 years of indefatigable fight for truth and justice. I was a physics student at Tsinghua University in 1989. The previous summer of 1988, I organized the first and only free election of the student union of my department. I was amazed and encouraged by the enthusiasm of the students to participate in the process of self-governing. There was a palpable sense for change in the college campuses. When Hu Yaobang died on April 15, 1989. His death triggered immediately widespread protests in top universities of Beijing, because he was removed from the position of the General Secretary of CCP in 1987 for his sympathy towards the protesting students and for being too open minded. The next day I went to Tiananmen Square to offer a flower wreath with my roommates of Tsinghua University. To my pleasant surprise, my words on the wreath was published the next day by a national official newspaper. We were the first group to go to Tiananmen Square to mourn Hu Yaobang. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual Report 2019

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 36–743 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate JAMES P. MCGOVERN, Massachusetts, MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Co-chair Chair JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TOM COTTON, Arkansas THOMAS SUOZZI, New York STEVE DAINES, Montana TOM MALINOWSKI, New Jersey TODD YOUNG, Indiana BEN MCADAMS, Utah DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California CHRISTOPHER SMITH, New Jersey JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon BRIAN MAST, Florida GARY PETERS, Michigan VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Department of State, To Be Appointed Department of Labor, To Be Appointed Department of Commerce, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed JONATHAN STIVERS, Staff Director PETER MATTIS, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT C O N T E N T S Page I. -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2003: China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong and Macau)

Page 1 of 66 China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau) Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 (Note: Also see the section for Tibet, the report for Hong Kong, and the report for Macau.) The People's Republic of China (PRC) is an authoritarian state in which, as directed by the Constitution, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP or Party) is the paramount source of power. Party members hold almost all top government, police, and military positions. Ultimate authority rests with the 24-member political bureau (Politburo) of the CCP and its 9-member standing committee. Leaders made a top priority of maintaining stability and social order and were committed to perpetuating the rule of the CCP and its hierarchy. Citizens lacked both the freedom peacefully to express opposition to the Party-led political system and the right to change their national leaders or form of government. Socialism continued to provide the theoretical underpinning of national politics, but Marxist economic planning has given way to pragmatism, and economic decentralization increased the authority of local officials. The Party's authority rested primarily on the Government's ability to maintain social stability; appeals to nationalism and patriotism; Party control of personnel, media, and the security apparatus; and continued improvement in the living standards of most of the country's 1.3 billion citizens. The Constitution provides for an independent judiciary; however, in practice, the Government and the CCP, at both the central and local levels, frequently interfered in the judicial process and directed verdicts in many high-profile cases.