Analysis of Changes in Natural Gas Physical Flows for Europe Via Ukraine in 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System

The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System Chi Kong Chyong, Pierre Noël and David M. Reiner September 2010 CWPE 1051 & EPRG 1026 The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System EPRG Working Paper 1026 Cambridge Working Paper in Economics 1051 Chi Kong Chyong, Pierre Noёl and David M. Reiner Abstract We calculate the total cost of building Nord Stream and compare its levelised unit transportation cost with the existing options to transport Russian gas to western Europe. We find that the unit cost of shipping through Nord Stream is clearly lower than using the Ukrainian route and is only slightly above shipping through the Yamal-Europe pipeline. Using a large-scale gas simulation model we find a positive economic value for Nord Stream under various scenarios of demand for Russian gas in Europe. We disaggregate the value of Nord Stream into project economics (cost advantage), strategic value (impact on Ukraine’s transit fee) and security of supply value (insurance against disruption of the Ukrainian transit corridor). The economic fundamentals account for the bulk of Nord Stream’s positive value in all our scenarios. Keywords Nord Stream, Russia, Europe, Ukraine, Natural gas, Pipeline, Gazprom JEL Classification L95, H43, C63 Contact [email protected] Publication September 2010 EPRG WORKING PAPER Financial Support ESRC TSEC 3 www.eprg.group.cam.ac.uk The Economics of the Nord Stream Pipeline System1 Chi Kong Chyong* Electricity Policy Research Group (EPRG), Judge Business School, University of Cambridge (PhD Candidate) Pierre Noёl EPRG, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge David M. Reiner EPRG, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge 1. -

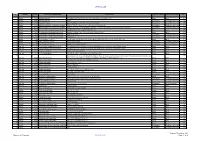

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Russian Chess on Gas Politics: Evaluation of Turkish Stream

RUSSIAN CHESS ON GAS POLITICS: EVALUATION OF TURKISH STREAM by Oğuzhan Akyener and Çağrı Şirin HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF RUS- INTRODUCTION SIAN GAS EXPORT TO EU Turkish Stream Pipeline Project (TSP) is the result of the altering Russian gas supply pol- Initially, existing key gas pipelines feeding icies toward European Union (EU). Due to the Europe will be described shortly in the flustering disputes over Ukraine, initial step concept of the historical overview of Russian was planned as to bypass Ukraine with a new gas export to EU. Latter, the previous steps before the Turkish Stream and South Stream "Due to flustering dis- standalone pipeline that will transit Russian gas to Eastern Europe. However, increasing Pipeline will be adverted. After mentioning the infrastructural situation, customer char- putes over Ukraine, initial conflicts between EU and Bulgarian govern- ment made Russia take a step forward with acteristics of Ukraine and the third energy package of EU will also be analyzed. step was planned as to a new standalone pipeline project, which is named as Turkish Stream. bypass Ukraine with a EXISTING KEY PIPELINES TO FEED THE EUROPE In the concept of Turkish Stream, Russia is new standalone pipeline planning to transport the gas through Black Russia gas export to Europe started before Sea and Turkey and sell it in the Greek border that will transit Russian 1940’s with the small volumes of export to of Turkey. This means, Russia will not have Poland. While considering the small portion to deal with the transportation of her gas in- gas to Eastern Europe." of consumption volumes, location of the ex- side EU’s borders. -

Transport and Transportation Заочне Навчання

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ ХАРКІВСЬКА НАЦІОНАЛЬНА АКАДЕМІЯ МІСЬКОГО ГОСПОДАРСТВА Н. І. Видашенко А. В. Сміт TRANSPORT AND TRANSPORTATION Збірник текстів і завдань з дисципліни ‘Іноземна мова ( за професійним спрямуванням ) ( англійська мова)’ (для організації самостійної роботи студентів 1 курсу заочної форми навчання напряму ‘Електромеханіка ’ спеціальностей 6.050702 – ‘Електричний транспорт ’, ‘Електричні системи комплекси транспортних засобів ’, ‘Електромеханічні системи автоматизації та електропривод ’) Харків – ХНАМГ – 2009 TRANSPORT AND TRANSPORTATION. Збірник текстів і завдань з дисципліни ‘Іноземна мова ( за професійним спрямуванням ) ( англійська мова )’ (для організації самостійної роботи студентів 1 курсу заочної форми навчання напряму ‘Електромеханіка ’ спеціальностей 6.050702 – ‘Електричний транспорт ’, ‘Електричні системи комплекси транспортних засобів ’, ‘Електромеханічні системи автоматизації та електропривод ’) /Н. І. Видашенко , А. В. Сміт ; Харк . нац . акад . міськ . госп -ва . – Х.: ХНАМГ , 2009. – 60 с. Автори : Н. І. Видашенко , А. В. Cміт Збірник текстів і завдань побудовано за вимогами кредитно -модульної системи організації навчального процесу ( КМСОНП ). Рекомендовано для студентів електромеханічних спеціальностей . Рецензент : доцент кафедри іноземних мов , к. філол . н. Ільєнко О. Л. Затверджено на засіданні кафедри іноземних мов , протокол № 1 від 31 серпня 2009 року © Видашенко Н. І. © Сміт А. В. © ХНАМГ , 2009 2 CONTENTS ВСТУП 4 UNIT ONE. ENGLISH IN OUR LIFE 5 UNIT TWO. HIGHER EDUCATION 17 UNIT THREE. MEANS OF TRANSPORTATION 21 UNIT FOUR. CITY TRAFFIC 40 UNIT FIVE. TYPES OF PAYMENT IN CITY TRAFFIC 47 UNIT SIX. DOUBLED TRANSPORT 52 UNIT SEVEN. BUSES IN LONDON 54 SOURCES 59 3 ВСТУП Даний збірник текстів призначений для студентів 1 курсу заочної форми навчання напряму ‘Електромеханіка ’, що вивчають англійську мову . -

The Southern Gas Corridor

Energy July 2013 THE SOUTHERN GAS CORRIDOR The recent decision of The State Oil Company of The EU Energy Security and Solidarity Action Plan the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) and its consortium identified the development of a Southern Gas partners to transport the Shah Deniz gas through Corridor to supply Europe with gas from Caspian Southern Europe via the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) and Middle Eastern sources as one of the EU’s is a key milestone in the creation of the Southern “highest energy securities priorities”. Azerbaijan, Gas Corridor. Turkmenistan, Iraq and Mashreq countries (as well as in the longer term, when political conditions This Briefing examines the origins, aims and permit, Uzbekistan and Iran) were identified development of the Southern Gas Corridor, including as partners which the EU would work with to the competing proposals to deliver gas through it. secure commitments for the supply of gas and the construction of the pipelines necessary for its Background development. It was clear from the Action Plan that the EU wanted increased independence from In 2007, driven by political incidents in gas supplier Russia. The EU Commission President José Manuel and transit countries, and the dependence by some Barroso stated that the EU needs “a collective EU Member States on a single gas supplier, the approach to key infrastructure to diversify our European Council agreed a new EU energy and energy supply – pipelines in particular. Today eight environment policy. The policy established a political Member States are reliant on just one supplier for agenda to achieve the Community’s core energy 100% of their gas needs – this is a problem we must objectives of sustainability, competitiveness and address”. -

Visegrad Group Facing the Nord Stream and South Stream Gas Pipeline Projects

VISEGRAD GROUP FACING THE NORD STREAM AND SOUTH STREAM GAS PIPELINE PROJECTS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ZAHİDE TUĞBA ŞENTERZİ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AUGUST 2012 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Zahide Tuğba, Şenterzi Signature : iii ABSTRACT VISEGRAD GROUP FACING THE NORD STREAM AND SOUTH STREAM GAS PIPELINE PROJECTS Şenterzi, Zahide Tuğba MSc., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Mustafa Türkeş August 2012, 163 pages This thesis analyzes the Visegrad Group’s stance toward the Russian-German Nord Stream and Russian-Italian South Stream gas pipeline projects, which aimed to circumvent the traditional energy routes situated in Central Europe and Eastern Europe. The level of the Visegrad Group’s dependency on inherited Soviet gas pipeline routes is examined alongside the Visegrad Group’s policy setting ability within the group itself and in the European Union. The thesis also traces the evolution of energy relations between Europe and Russia and Visegrad Group’s adaptation to the new state of affairs after the collapse of the Soviet Union, particularly with respect to energy issues. It is argued that despite all differences, Visegrad Group members are able to set a cooperation platform at times of crisis and develop common energy strategies. -

Rolling Stock Orders: Who

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE HEADLINES l Toronto’s streetcar advocates fight back l UK’s Midland Metro expansion approved l Democrats propose more US light rail ROLLING STOCK ORDERS: WHO... WHAT... HOW MUCH? Ukrainian tramways under the microscope US streetcar trends: Mixed fleets: How technology Lessons from is helping change over a century 75 America’s attitude of experience to urban rail in Budapest APRIL 2012 No. 892 1937–2012 WWW. LRTA . ORG l WWW. TRAMNEWS . NET £3.80 TAUT_April12_Cover.indd 1 28/2/12 09:20:59 TAUT_April12_UITPad.indd 1 28/2/12 12:38:16 Contents The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association 128 News 132 APRIL 2012 Vol. 75 No. 892 Toronto light rail supporters fight back; Final approval for www.tramnews.net Midland Metro expansion; Obama’s budget detailed. EDITORIAL Editor: Simon Johnston 132 Rolling stock orders: Boom before bust? Tel: +44 (0)1832 281131 E-mail: [email protected] With packed order books for the big manufacturers over Eaglethorpe Barns, Warmington, Peterborough PE8 6TJ, UK. the next five years, smaller players are increasing their Associate Editor: Tony Streeter market share. Michael Taplin reports. E-mail: [email protected] 135 Ukraine’s road to Euro 2012 Worldwide Editor: Michael Taplin Flat 1, 10 Hope Road, Shanklin, Isle of Wight PO37 6EA, UK. Mike Russell reports on tramway developments and 135 E-mail: [email protected] operations in this former Soviet country. News Editor: John Symons 140 The new environment for streetcars 17 Whitmore Avenue, Werrington, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs ST9 0LW, UK. -

Security Aspects of the South Stream Project

BRIEFING PAPER Policy Department External Policies SECURITY ASPECTS OF THE SOUTH STREAM PROJECT FOREIGN AFFAIRS October 2008 JANUARY 2004 EN This briefing paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Foreign Affairs. It is published in the following language: English Author: Zeyno Baran, Director Center for Eurasian Policy (CEP), Hudson Institute www.hudson.org The author is grateful for the support of CEP Research Associates Onur Sazak and Emmet C. Tuohy as well as former CEP Research Assistant Rob A. Smith. Responsible Official: Levente Császi Directorate-General for External Policies of the Union Policy Department BD4 06 M 55 rue Wiertz B-1047 Brussels E-mail: [email protected] Publisher European Parliament Manuscript completed on 23 October 2008. The briefing paper is available on the Internet at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/activities/committees/studies.do?language=EN If you are unable to download the information you require, please request a paper copy by e-mail : [email protected] Brussels: European Parliament, 2008. Any opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament. © European Communities, 2008. Reproduction and translation, except for commercial purposes, are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and provided the publisher is given prior notice and supplied with a copy of the publication. EXPO/B/AFET/2008/30 October 2008 PE 388.962 EN CONTENTS SECURITY ASPECTS OF THE SOUTH STREAM PROJECT ................................ ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................iii 1. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 1 2. THE RUSSIAN CHALLENGE................................................................................... 2 2.1. -

Nord Stream 2

Updated August 24, 2021 Russia’s Nord Stream 2 Natural Gas Pipeline to Germany Nord Stream 2, a natural gas pipeline nearing completion, is which accounted for about 48% of EU natural gas imports expected to increase the volume of Russia’s natural gas in 2020. Russian gas exports to the EU were up 18% year- export capacity directly to Germany, bypassing Ukraine, on-year in the first quarter of 2021. Factors behind reliance Poland, and other transit states (Figure 1). Successive U.S. on Russian supply include diminishing European gas Administrations and Congresses have opposed Nord Stream supplies, commitments to reduce coal use, Russian 2, reflecting concerns about European dependence on investments in European infrastructure, Russian export Russian energy and the threat of increased Russian prices, and the perception of many Europeans that Russia aggression in Ukraine. The German government is a key remains a reliable supplier. proponent of the pipeline, which it says will be a reliable Figure 1. Nord Stream Gas Pipeline System source of natural gas as Germany is ending nuclear energy production and reducing coal use. Despite the Biden Administration’s stated opposition to Nord Stream 2, the Administration appears to have shifted its focus away from working to prevent the pipeline’s completion to mitigating the potential negative impacts of an operational pipeline. Some critics of this approach, including some Members of Congress and the Ukrainian and Polish governments, sharply criticized a U.S.-German joint statement on energy security, issued on July 21, 2021, which they perceived as indirectly affirming the pipeline’s completion. -

Brussels Admits EU Law Does Not Apply to Nord Stream 2 the European Commission Has Admitted There Is No Legal Ground to Apply Matter Before the End of the Year

Energy Reproduced with permission by Energy Intelligence for Oxford Institute of Energy Studies Intelligence Issue Vol.17, No. 186, Thursday, September 21, 2017 Vol. 17, No. 186 Thursday, September 21, 2017 Special Reprint from International Oil Daily for Oxford Institute of Energy Studies . Copyright © 2017 Energy Intelligence Group. Unauthorized copying, reproduc- ing or disseminating in any manner, in whole or in part, including through intranet or internet posting, or electronic forwarding even for internal use, is prohibited. Brussels Admits EU Law Does Not Apply to Nord Stream 2 The European Commission has admitted there is no legal ground to apply matter before the end of the year. EU energy laws to Gazprom’s Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project despite its Observers believe Brussels’ mandate is plagued with problems, starting long-drawn opposition to the plan. with the fact that it would not ensure that Moscow must negotiate. PrintIn a Sep. 12 letter sent to a member of the European Parliament by the "If the commission does secure the mandate, it would acquire certain le- commission and leaked to the press, the commission’s legal service said gitimacy to negotiate, and it would be difficult for Russia to refuse entering that the application of the EU’s Third Energy Package regulations to off- negotiations; nonetheless Russia could still refuse to negotiate,” according shore import pipelines such as Nord Stream 2 "would raise specific legal to Katja Yafimava, senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy and practical questions, arising ... from the fact that Union rules cannot be Studies. Even if Russia does agree to negotiate, Yafimava doubts whether made unilaterally binding on the national authorities of third countries.” Moscow will accept the application of EU energy law to the project. -

Statoil-2015-Statutory-Report.Pdf

2015 Statutory report in accordance with Norwegian authority requirements © Statoil 2016 STATOIL ASA BOX 8500 NO-4035 STAVANGER NORWAY TELEPHONE: +47 51 99 00 00 www.statoil.com Cover photo: Øyvind Hagen Statutory report 2015 Board of directors report ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 The Statoil share ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Our business ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Group profit and loss analysis .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Cash flows ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Annoucements of Conducting Procurement Procedures

Bulletin No�24(98) June 12, 2012 Annoucements of conducting 13443 Ministry of Health of Ukraine procurement procedures 7 Hrushevskoho St., 01601 Kyiv Chervatiuk Volodymyr Viktorovych tel.: (044) 253–26–08; 13431 National Children’s Specialized Hospital e–mail: [email protected] “Okhmatdyt” of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: 28/1 Chornovola St., 01135 Kyiv www.tender.me.gov.ua Povorozniuk Volodymyr Stepanovych Procurement subject: code 24.42.1 – medications (Imiglucerase in flasks, tel.: (044) 236–30–05 400 units), 319 pcs. Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Supply/execution: 29 Berezniakivska St., 02098 Kyiv; during 2012 www.tender.me.gov.ua Procurement procedure: open tender Procurement subject: code 24.42.1 – medications, 72 lots Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, office 138 Supply/execution: at the customer’s address; July – December 2012 Submission: at the customer’s address, office 138 Procurement procedure: open tender 29.06.2012 10:00 Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, Opening of tenders: at the customer’s address, office 138 economics department 29.06.2012 12:00 Submission: at the customer’s address, economics department Tender security: bank guarantee, deposit, UAH 260000 26.06.2012 10:00 Terms of submission: 90 days; not returned according to part 3, article 24 of the Opening of tenders: at the customer’s address, office of the deputy general Law on Public Procurement director of economic issues Additional information: For additional information, please, call at 26.06.2012 11:00 tel.: (044) 253–26–08, 226–20–86.