More Trust, Less Control – Less Work?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007

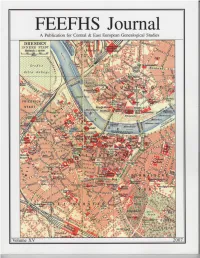

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007 FEEFHS Journal Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? The Federation of East European Family History Societies Guest Editor: Kahlile B. Mehr. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group of Managing Editor: Thomas K. Edlund American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven societies FEEFHS Executive Council had accepted its concept as founding members. Each year since then FEEFHS has grown in size. FEEFHS now represents nearly two 2006-2007 FEEFHS officers: hundred organizations as members from twenty-four states, five Ca- President: Dave Obee, 4687 Falaise Drive, Victoria, BC V8Y 1B4 nadian provinces, and fourteen countries. It continues to grow. Canada. [email protected] About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi- 1st Vice-president: Brian J. Lenius. [email protected] purpose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 2nd Vice-president: Lisa A. Alzo ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, online services, insti- 3rd Vice-president: Werner Zoglauer tutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and other Secretary: Kahlile Mehr, 412 South 400 West, Centerville, UT. ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes organiza- [email protected] tions representing all East or Central European groups that have ex- Treasurer: Don Semon. [email protected] isting genealogy societies in North America and a growing group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from novices to Other members of the FEEFHS Executive Council: professionals. Founding Past President: Charles M. Hall, 4874 S. 1710 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84117-5928 Goals and Purposes: Immediate Past President: Irmgard Hein Ellingson, P.O. -

FOOTPRINTS in the SNOW the Long History of Arctic Finland

Maria Lähteenmäki FOOTPRINTS IN THE SNOW The Long History of Arctic Finland Prime Minister’s Office Publications 12 / 2017 Prime Minister’s Office Publications 12/2017 Maria Lähteenmäki Footprints in the Snow The Long History of Arctic Finland Info boxes: Sirpa Aalto, Alfred Colpaert, Annette Forsén, Henna Haapala, Hannu Halinen, Kristiina Kalleinen, Irmeli Mustalahti, Päivi Maria Pihlaja, Jukka Tuhkuri, Pasi Tuunainen English translation by Malcolm Hicks Prime Minister’s Office, Helsinki 2017 Prime Minister’s Office ISBN print: 978-952-287-428-3 Cover: Photograph on the visiting card of the explorer Professor Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld. Taken by Carl Lundelius in Stockholm in the 1890s. Courtesy of the National Board of Antiquities. Layout: Publications, Government Administration Department Finland 100’ centenary project (vnk.fi/suomi100) @ Writers and Prime Minister’s Office Helsinki 2017 Description sheet Published by Prime Minister’s Office June 9 2017 Authors Maria Lähteenmäki Title of Footprints in the Snow. The Long History of Arctic Finland publication Series and Prime Minister’s Office Publications publication number 12/2017 ISBN (printed) 978-952-287-428-3 ISSN (printed) 0782-6028 ISBN PDF 978-952-287-429-0 ISSN (PDF) 1799-7828 Website address URN:ISBN:978-952-287-429-0 (URN) Pages 218 Language English Keywords Arctic policy, Northernness, Finland, history Abstract Finland’s geographical location and its history in the north of Europe, mainly between the latitudes 60 and 70 degrees north, give the clearest description of its Arctic status and nature. Viewed from the perspective of several hundred years of history, the Arctic character and Northernness have never been recorded in the development plans or government programmes for the area that later became known as Finland in as much detail as they were in Finland’s Arctic Strategy published in 2010. -

Your Guide to Western Uusimaa History

YOUR GUIDE TO WESTERN UUSIMAA HISTORY, RECREATION AND SIGHTS Pomoväst r.f. Welcome to Western Uusimaa! Western Uusimaa is fantastic. By its form it is a long region which starts in Kirkkonummi near to Helsinki and goes on to Hanko Cape, the southernmost point of the Finnish mainland. Whether you are a newcomer or already well acquainted with the region, there is always a lot to see and experience: - wonderful open-air recreation areas - magnificent medieval buildings - interesting churches - exciting museums The aim of this guide is to open your eyes to see the wonders of Western Uusimaa. In addition to the attractions presented on the cd-rom, there is much to discover when it comes to services in Western Uusimaa: there are cosy restaurants, nice hotels and interesting shops. Information on opening hours is available on the Internet once you have acquainted yourself with the sights presented on this guide. Welcome! Churches in the region: Index: Museums: Hanko Hanko The Church of Hanko card 7 Hanko cards 1-15 Bengtskär, Lighthouse Museum card 2 The Orthodox Church of Hanko Ekenäs cards 17-32 Hanko Front Museum card 6 card 9 Karis cards 33-44 Hanko Museum card 8 The Church of Lappohja card 11 Pohja cards 45-51 The Chapel of Täktom card 14 Ingå cards 53-63 Ekenäs Siuntio cards 64-72 Bromarf homestead museum card 18 Ekenäs Kirkkonummi cards 73-89 Ekenäs Museum card 23 Snappertuna Folk Museum card 27 Bromarf Church card 19 Tenala homestead museum card 29 Ekenäs Church card 22 The Hospital Museum of Western Uusimaa Snappertuna Church card 28 card 32 Tenala Church card 30 Karis Mjölbollstad sanatorium museum card 40 Karis Mustio Castle Museum card 44 St. -

Och Logistik

Åbo Underrättelser fredag 21 november tema Sjöfart och logistik Finländskt bygge avgår Åbo hamn knutpunkt Pontonen Big Partner är från Southampton. inom linjetrafiken den första nya på 20 år Sidan 2–3 Sidan 12–13 Sidan 18–19 FREDAG 21 NOVEMBER 2008 FREDAG 21 NOVEMBER 2008 2 SJÖFART ÅBO UNDERRÄTTELSER: TEL: (02) 274 9900. E-POST: [email protected] ÅBO UNDERRÄTTELSER: TEL: (02) 274 9900. E-POST: [email protected] SJÖFART 3 På kryssning med Åbos stolthet I snål vind och med juniregnet hängande i luften lägger världens största kryssningsfartyg ut från Southampton. Pär-Henrik Sjöström Vid middagstid på lördag omfattar bl.a. ståuppkomik, börjar de förväntansfulla musik och dansföreställ- passagerarna samlas i termi- ningar. På fartygets prome- nalen i Southampton. Allt är nadstråk Royal Promenade väl organiserat. Inom tre ordnas flera kvällar under timmar är alla passagerare resan tillställningar med incheckade och installerade musik eller karneval som ombord. tema. Världens största kryss- En grupp av passagerare ningsfartyg, Independence som verkar stortrivas of the Seas, byggd vid Aker ombord är ungdomarna – Aktiva soldyrkare. Kryssningar förknippas med lata dagar vid Yards varv i i Åbo är redo kryssningsvärden säger att simbassängen. Men det finns mycket annat att göra ombord. för avfärd. det finns 600 tonåringar Foto: Pär-Henrik Sjöström En liten skara har samlats med på denna resa och för på stranden för att följa med dem ordnas speciella pro- när fartyget lägger ut från gram och aktiviteter. kajen och börjar stäva mot Ombord finns även många Solent – sundet mellan fast- rörelsehämmade personer. landet och Isle of Wight. Fartyget har planerats så att det ska vara möjligt att röra Gästerna har på förhand till- sig så enkelt som möjligt i delats plats i någon av de tre rullstol och personalen huvudrestaurangerna som assisterar välvilligt när det fått sina namn efter Shakes- behövs, som vid iland- och pearekaraktärer. -

2. De Första Åren Av Rysk Ockupation

2009 REPRESSION OCH LEGITIMERING – RYSK MAKTUTÖVNING I ÅBO GENERALGUVERNEMENT 1717 - 1721 Repression och legitimering – rysk maktutövning i Åbo generalguvernement 1717 - 1721 Civilförvaltningen under en ockupation med jämförande utblickar Hilding Klingenberg ÅBO 2009 ÅBO AKADEMIS FÖRLAG – ÅBO AKADEMI UNIVERSITY PRESS CIP Cataloguing in Publication Klingenberg, Hilding Repression och legitimering – rysk maktut- övning i Åbo generalguvernement 1717 – 1721 : civilförvaltningen under en ockupation med jämförande utblickar / Hilding Klingenberg. – Åbo : Åbo Akademis förlag, 2009. Diss.: Åbo Akademi. – Summary. ISBN 978-951-765-496-8 ISBN 978-951-765-496-8 ISBN 978-951-765-497-5 (digital) Oy Nordprint Ab Helsingfors 2009 Förord I början av 1960-talet stiftade jag vid mitt pro gradu-arbete bekantskap med källorna till stora ofredens historia. Det var dåvarande, senare framlidne, professorn i nordisk historia vid Åbo Akademi Oscar Niku- la som kopplade in mig på det spåret. Redan då förvånade mig den äld- re traditionen inom historieskrivningen som satte likhetstecken mellan den ryska ockupationens militära och civila förvaltningsskeden. Att man ibland helt abstraherade från de ryska källorna resulterade i en tämligen ensidig bild av tiden 1717 – 1721, dvs. ockupationens civil- förvaltningsperiod. Detta framgick, tyckte jag mig kunna se, tydligt t.ex. redan vid första genomläsningen av den ryska förvaltningschefens brev till sin förman i S:t Petersburg. Jag fattade som ung magister be- slutet, att om möjligt, senare återkomma till tematiken gällande den ryska maktutövningen under stora ofreden. ”Audiatur aut altera pars”, för att följa en av den romerska rättens huvudprinciper. Mina uppgifter inom yrkeslivet lade emellertid länge hinder i vägen för en fortsatt forskning. Under min andra forskningsperiod, som inleddes hösten 2004 med arbetet på först min licentiatavhandling och därefter föreliggande dis- sertation, har jag fått ovärderligt stöd från många håll. -

Voima Käyttö Kraft Drift Suomen Konepäällystöliiton & Julkaisu • 11–12/2015

Voima Käyttö Kraft Drift Suomen Konepäällystöliiton & julkaisu • 11–12/2015 Hyvää Joulua ja onnellista Uutta Vuotta God Jul och gott Nytt År Voima & Käyttö • 11–12/2015 • 1 • Sisällys • • Pääkirjoitus • Chefredaktör • Voima Käyttö Kraft Drift Suomen Konepäällystöliiton & ammatti- ja tiedotuslehti 109. vuosikerta Pääkirjoitus ........................................................................................ 3 STTK:n puheenjohtaja Antti Palola: STTK:n hallitus ei hyväksy pakkolainsäädäntöä .............................. 4 Lastenkodinkuja 1 STTK:n johtaja Katarina Murto: 00180 Helsinki Valehtelevat ministerit Paikallinen sopiminen ei saa murentaa sopimusjärjestelmää puh. (09) 5860 4815 ja yleissitovuutta ................................................................................. 4 faksi (09) 6948 798 STTK tyytyväinen vuorotteluvapaa-järjestelmän säilymiseen ......... 4 email [email protected] ina oppii jotain uutta! Nyt koko joukko ministereitä on ka taas on vain työntekijäpuoli jonka pitäisi joustaa ja heiken- Sähkön käyttö laski syyskuussa ja kulutus oli aloittanut virallisen valehtelun. Tämä kolmen S:n hallitus tää sisältöä eli sopimuksia, kun yritykset jakavat yhä suurempia 0,7 % edellisvuotta pienempi ............................................................ 5 Päätoimittaja on ollut muutoinkin epäpätevä ja nyt on aloitettu suora- voittoja osakkeenomistajille ja johdolle. Suomessa nämä ylisuu- Taloudesta tiistaina: Leif Wikström nainen valehteluiden ryöppy. Aikanaan ministeriin pystyi edes ret palkkiot -

Tutkintaselostus B1/2003 M

Tutkintaselostus B1/2003 M Matkustaja-autolautta ISABELLA, pohjakosketus Staholmin luona Ahvenanmaalla 20.12.2001 Passagerar-bilfärjan ISABELLA, bottenkänningen vid Staholm , Åland 20.12.2001 LIITTEET, BILAGOR LIITE 1, BILAGA 1 Raportti ms ISABELLAn automaattiohjauksen toiminnasta ennen pohja- kosketusta Björkössä 20.12.2001 LIITE 2, BILAGA 2 Resultaten av enkäten bland passagerarna LIITE 3, BILAGA 3 Linjaluotsausjärjestelmän synty ja kehitys Linjelotssystemets tillkomst och utveckling LIITE 1 BILAGA 1 APPENDIX 1 Raportti ms ISABELLAn automaattiohjauksen toiminnasta ennen pohjakosketusta Björkössä 20.12.2001 6LPXOFR2\ 5DSRUWWL5 06,6$%(//$1$8720$$77,2+-$8.6(1 72,0,11$67$(11(132+-$.26.(7867$ %-g5.g66b 6LPXOFR2\ 5VLYX 6,6b//<6/8(77(/2 -2+'$172 $7/$61$&26$8720$$77,2+-$8.6(172,0,17$3(5,$$77((67$ $8720$$77,2+-$8.6(1.b<77b<7<0,6(67b(11(132+-$.26.(7867$ .89$7-$ .89$7-$ .89$ .$577$ 0$37MD0$30 .$577$ 0$30 6LPXOFR2\ 7HOLQW .RLYXYLLWD$ )D[LQW ),1(VSRR (PDLOMDDNNROHKWRVDOR#VLPXOFRLQHWIL )LQODQG 6LPXOFR2\ 5VLYX -2+'$172 6LPXOFR 2\ RQ VDDQXW 2QQHWWRPXXVWXWNLQWDNHVNXNVHOWD WHKWlYlNVL WXWNLD MD VHOYLWWll 06,VDEHOODQ 1DFRV QDYLJRLQWLMlUMHVWHOPlQ DXWRPDDWWLRKMDXNVHQ WRLPLQWDD HQQHQ SRKMDNRVNHWXVWD%M|UN|VVl 6HOYLW\VW\|VVl Nl\WHWWLLQ VHXUDDYLD 2QQHWWRPXXVWXWNLQWDNHVNXNVHOWD MD 9LNLQJ /LQH 2\OWl VDDWXMDWLHWRMDMDWDOOHQWHLWD D 3DLNDQQXVODLWWHHVHHQ '*36 MDK\UUlNRPSDVVLLQN\WNHW\Q$16RKMHOPLVWRQ $GYDQFHG 1DYLJDWLRQ6RIWZDUH UHLWWLWDOOHQQH*36MDDVHWXVWLHGRVWR$16,1, E $OXNVHQ QDYLJRLQWLMlUMHVWHOPlQ UHLWWLVXXQQLWHOPD W MRND HL ROOXW DNWLLYLQHQ WDSDKWXPDDLNDDQ -

Tanssiva Kaupunki Societas Scientiarum Fennica

TANSSIVA KAUPUNKI SOCIETAS SCIENTIARUM FENNICA Finska Vetenskaps-Societeten, grundad 1838, är Finlands äldsta vetenskapsakademi, som publicerar forskning, utdelar stipendier och pris, tar initiativ och håller möten med föredrag. Societeten inledde 1996 ett publiceringssamarbete med syskonakademin Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. Vuonna 1838 perustettu Suomen Tiedeseura on Suomen vanhin tiedeakatemia, joka julkaisee tutkimuksia, myöntää tutkimusavustuksia ja palkintoja, tekee aloitteita ja järjestää kokouksia. Seura aloitti 1996 julkaisuyhteistyön sisarjärjestönsä Suomalaisen Tiedeakatemian kanssa. The Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters, founded in 1838, is the oldest scholarly academy of Finland. It publishes research, awards research grants and prizes, takes initiatives and organizes meetings. In 1996 the Society established cooperation with its sister organizarion the Finnish Academy of Sciences and Letters. Bidrag till kännedom av Finlands natur och folk Serien, som grundades år 1857, publicerar undersökningar om Finlands natur, befolkning och samhällsförhållanden. Utkommer med oregelbundna intervaller. Bidrag till kännedom av Finlands natur och folk utges inom ramen för publiceringssamarbetet med Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. Vuonna 1857 perustettu sarja julkaisee Suomen luontoa, väestöä ja yhteiskuntaoloja käsitteleviä tutkielmia. Ilmestyy epäsäännöllisin välein. Bidrag till kännedom av Finlands natur och folk julkaistaan osana Suomen Tiedeseuran ja Suomalaisen Tiedeakatemian välistä julkaisuyhteistyötä. The series, founded in 1857, publishes -

Martinranta 2 / 2014 Sisällys

Martinranta 2 / 2014 Sisällys 3 Pääkirjoitus 6 Telakkatoiminnan historiaa 3 16 Martin Maailmankylä 18 Kaupunginosien nimikkokasvit 22 Turun kätketyt aarteet 24 Muuttuvaa kaupunkieläimistöä ihmettelemässä 27 Halisten retki, vesilaitoshistoriaa 32 Tyylikästä arkkitehtuuria Martissa 35 Ympäristöjaosto toimii 37 Tapahtumakalenteri 38 Jäsenalennukset 39 Seuran tiedot Julkaisija: Martinrantaseura ry Lehden toimituskunta: Jouni Liuke, vastaava toimittaja Leo Lindstedt, Heimo Kumlander, Tapani Järvinen Valokuvat toimituksen, ellei toisin mainita Taitto ja layout: Matti Koskimies, painopaikka X-Copy Kansikuva: Rusokirsikka nimettiin Martin kaupunginosien IV-V nimikkopuuksi työryhmän pitkän harkinnan jälkeen. Puita istutettiin kulttuuripääkaupunkivuonna Martin alueelle Martinsillan pieleen ja alemmaksi jokivarteen Manillan edustalle. Kuvassamme toukokuulta rusokirsikka oli täydessä kukassaan Aurajoen rannalla Itäisen Rantakadun 44 kohdalla. 2 Pääkirjoitus Jouni Liuke Kotiseutujuhlaa Sanotaan, että ikä tuo mukanaan vii- sautta. Vuosi 2014 on kotiseututyössä oikea viisauden juhlavuosi: Suomalai- sen kotiseutuliikkeen syntysanat lausut- tiin 120 vuotta sitten 24.3.1894 Lohjal- la. Silloin perustettiin Suomen ensim- mäinen kotiseutuyhdistys nimeltään Lohjan Kotiseutututkimuksen ystävät. pitämällä yhteyttä kunnallishallintoon Kotiseututyönalkuonlöydettävissäkui- ja pyrkimällä vaikuttamaan päätök- tenkin jo yli 350 vuoden takaa, kun sentekoon. Seura on tehnyt ja tekee Ruotsissa perustettiin Antikviteettikol- aloitteita ja esityksiä sekä laatii kanna-