Orwell and Pynchon V. Bazooka Joe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review 330 Fall 2019 SFRA

SFRA RREVIEWS, ARTICLES,e ANDview NEWS FROM THE SFRA SINCE 1971 330 Fall 2019 FEATURING Area X: Five Years Later PB • SFRA Review 330 • Fall 2019 Proceedings of the SFRASFRA 2019 Review 330Conference • Fall 2019 • 1 330 THE OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF THE Fall 2019 SFRA MASTHEAD ReSCIENCE FICTIONview RESEARCH ASSOCIATION SENIOR EDITORS ISSN 2641-2837 EDITOR SFRA Review is an open access journal published four times a year by Sean Guynes Michigan State University the Science Fiction Research Association (SFRA) since 1971. SFRA [email protected] Review publishes scholarly articles and reviews. The Review is devoted to surveying the contemporary field of SF scholarship, fiction, and MANAGING EDITOR media as it develops. Ian Campbell Georgia State University [email protected] Submissions ASSOCIATE EDITOR SFRA Review accepts original scholarly articles; interviews; Virginia Conn review essays; individual reviews of recent scholarship, fiction, Rutgers University and media germane to SF studies. [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR All submissions should be prepared in MLA 8th ed. style and Amandine Faucheux submitted to the appropriate editor for consideration. Accepted University of Louisiana at Lafayette pieces are published at the discretion of the editors under the [email protected] author's copyright and made available open access via a CC-BY- NC-ND 4.0 license. REVIEWS EDITORS NONFICTION EDITOR SFRA Review does not accept unsolicited reviews. If you would like Dominick Grace to write a review essay or review, please contact the appropriate Brescia University College [email protected] review editor. For all other publication types—including special issues and symposia—contact the editor, managing, and/or ASSISTANT NONFICTION EDITOR associate editors. -

Arch : Northwestern University Institutional Repository

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Myth and the Modern Problem: Mythic Thinking in Twentieth-Century Britain A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Matthew Kane Sterenberg EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2007 2 © Copyright by Matthew Kane Sterenberg 2007 All Rights Reserved 3 ABSTRACT Myth and the Modern Problem: Mythic Thinking in Twentieth-Century Britain Matthew Sterenberg This dissertation, “Myth and the Modern Problem: Mythic Thinking in Twentieth- Century Britain,” argues that a widespread phenomenon best described as “mythic thinking” emerged in the early twentieth century as way for a variety of thinkers and key cultural groups to frame and articulate their anxieties about, and their responses to, modernity. As such, can be understood in part as a response to what W.H. Auden described as “the modern problem”: a vacuum of meaning caused by the absence of inherited presuppositions and metanarratives that imposed coherence on the flow of experience. At the same time, the dissertation contends that— paradoxically—mythic thinkers’ response to, and critique of, modernity was itself a modern project insofar as it took place within, and depended upon, fundamental institutions, features, and tenets of modernity. Mythic thinking was defined by the belief that myths—timeless rather than time-bound explanatory narratives dealing with ultimate questions—were indispensable frameworks for interpreting experience, and essential tools for coping with and criticizing modernity. Throughout the period 1900 to 1980, it took the form of works of literature, art, philosophy, and theology designed to show that ancient myths had revelatory power for modern life, and that modernity sometimes required creation of new mythic narratives. -

GORE VIDAL the United States of Amnesia

Amnesia Productions Presents GORE VIDAL The United States of Amnesia Film info: http://www.tribecafilm.com/filmguide/513a8382c07f5d4713000294-gore-vidal-the-united-sta U.S., 2013 89 minutes / Color / HD World Premiere - 2013 Tribeca Film Festival, Spotlight Section Screening: Thursday 4/18/2013 8:30pm - 1st Screening, AMC Loews Village 7 - 3 Friday 4/19/2013 12:15pm – P&I Screening, Chelsea Clearview Cinemas 6 Saturday 4/20/2013 2:30pm - 2nd Screening, AMC Loews Village 7 - 3 Friday 4/26/2013 5:30pm - 3rd Screening, Chelsea Clearview Cinemas 4 Publicity Contact Sales Contact Matt Johnstone Publicity Preferred Content Matt Johnstone Kevin Iwashina 323 938-7880 c. office +1 323 7829193 [email protected] mobile +1 310 993 7465 [email protected] LOG LINE Anchored by intimate, one-on-one interviews with the man himself, GORE VIDAL: THE UNITED STATS OF AMNESIA is a fascinating and wholly entertaining tribute to the iconic Gore Vidal. Commentary by those who knew him best—including filmmaker/nephew Burr Steers and the late Christopher Hitchens—blends with footage from Vidal’s legendary on-air career to remind us why he will forever stand as one of the most brilliant and fearless critics of our time. SYNOPSIS No twentieth-century figure has had a more profound effect on the worlds of literature, film, politics, historical debate, and the culture wars than Gore Vidal. Anchored by intimate one-on-one interviews with the man himself, Nicholas Wrathall’s new documentary is a fascinating and wholly entertaining portrait of the last lion of the age of American liberalism. -

The Predator Script

THE PREDATOR by Shane Black & Fred Dekker Based on the characters created by Jim Thomas & John Thomas REVISED DRAFT 04-17-2016 SPACE Cold. Silent. A billion twinkling stars. Then... A bass RUMBLE rises. Becomes a BONE-RATTLING ROAR as -- A SPACECRAFT RACHETS PAST CAMERA, fuel cables WHIPPING into frame, torn loose! Titanium SCREAMS as the ship DETACHES VIOLENTLY; shards CASCADING in zero gravity--! (NOTE: For reasons that will become apparent, we let us call this vessel “THE ARK.”) WIDER - THE ARK as it HURTLES AWAY from a docking gantry underneath a vastly LARGER SHIP it was attached to. Wobbly. Desperate. We’re witnessing a HIJACK. WIDER STILL - THE PREDATOR MOTHER SHIP DWARFS the escaping vessel. Looming; like a nautilus of molded black steel. INT. PREDATOR MOTHER SHIP Backed by the glow of compu-screens, a half-glimpsed alien -- A PREDATOR -- watches the receding ARK through a viewport. (NOTE: we see him mostly in shadow, full reveal to come). INT. SMALLER VESSEL (ARK) Emergency lights illuminate a dank, organic-looking interior. CAMERA MOVES PAST: EIGHT STASIS CYLINDERS Around the periphery. FROST clouds the cryotubes, prevents us from seeing the “passengers.” Finally, CAMERA ARRIVES AT -- A HULKING, DREAD-LOCKED FIGURE The pilot of this crippled ship. We do not see him fully either, but for the record? This is our “GOOD” PREDATOR.” HIS TALONS dance across a control panel; a shrill beep..! Predator symbols, but we get the idea: ERROR--ERROR--ERROR-- Our Predator TAPS more controls. Feverish. Until -- EXT. ARK A final tether COMES LOOSE, venting PLASMA energy, and -- 2. -

Texts and Other Fictions in Gore Vidalâ•Žs Burr

Studies in English, New Series Volume 11 Volumes 11-12 Article 29 1993 Texts and Other Fictions in Gore Vidal’s Burr Thomas Gladsky Central Missouri State University Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/studies_eng_new Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gladsky, Thomas (1993) "Texts and Other Fictions in Gore Vidal’s Burr," Studies in English, New Series: Vol. 11 , Article 29. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/studies_eng_new/vol11/iss1/29 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Studies in English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English, New Series by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gladsky: Texts and Other Fictions in Gore Vidal’s Burr TEXTS AND OTHER FICTIONS IN GORE VIDAL’S BURR Thomas Gladsky Central Missouri State University Over the years, Gore Vidal has campaigned furiously against theorists and writers of the new novel who, according to Vidal, “have attempted to change not only the form of the novel but the relationship between book and reader” (“French Letters” 67). In his essays, he has condemned the “misdirected” efforts of writers such as Donald Barthelme, John Gardner, Thomas Pynchon, John Barth, William Gass, and all those who come equipped with “formulas, theorems, signs, and diagrams because words have once again failed them” (“American Plastic” 102). In comparison, Vidal presents himself as a literary conservative, a defender of traditional form in fiction even though his own novels betray his willingness to penetrate beyond words and to experiment with form, especially in his series of historical novels. -

Visit to a Small Planet and the ―Fish out of Water‖ Comedy

Audience Guide Written and compiled by Jack Marshall July 8–August 6, 2011 Theatre Two, Gunston Arts Center Theater you can afford to see— plays you can’t afford to miss! About The American Century Theater The American Century Theater was founded in 1994. We are a professional company dedicated to presenting great, important, but overlooked American plays of the twentieth century . what Henry Luce called ―the American Century.‖ The company’s mission is one of rediscovery, enlightenment, and perspective, not nostalgia or preservation. Americans must not lose the extraordinary vision and wisdom of past playwrights, nor can we afford to surrender our moorings to our shared cultural heritage. Our mission is also driven by a conviction that communities need theater, and theater needs audiences. To those ends, this company is committed to producing plays that challenge and move all Americans, of all ages, origins and points of view. In particular, we strive to create theatrical experiences that entire families can watch, enjoy, and discuss long afterward. These audience guides are part of our effort to enhance the appreciation of these works, so rich in history, content, and grist for debate. The American Century Theater is a 501(c)(3) professional nonprofit theater company dedicated to producing significant 20th Century American plays and musicals at risk of being forgotten. The American Century Theater is supported in part by Arlington County through the Cultural Affairs Division of the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Cultural Resources and the Arlington Commission for the Arts. This arts event is made possible in part by the Virginia Commission on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts, as well as by many generous donors. -

Michael Krasny Has Interviewed a Wide Range of Major Political and Cultural Figures Including Edward Albee, Madeleine Albright

Michael Krasny has interviewed a wide range of major political and cultural figures including Edward Albee, Madeleine Albright, Sherman Alexei, Robert Altman, Maya Angelou, Margaret Atwood, Ken Auletta, Paul Auster, Richard Avedon, Joan Baez, Alec Baldwin, Dave Barry, Harry Belafonte, Annette Bening, Wendell Berry, Claire Bloom, Andy Borowitz, T.S. Boyle, Ray Bradbury, Ben Bradlee, Bill Bradley, Stephen Breyer, Tom Brokaw, David Brooks, Patrick Buchanan, William F. Buckley Jr, Jimmy Carter, James Carville, Michael Chabon, Noam Chomsky, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Cesar Chavez, Bill Cosby, Sandra Cisneros, Billy Collins, Pat Conroy, Francis Ford Coppola, Jacques Cousteau, Michael Crichton, Francis Crick, Mario Cuomo, Tony Curtis, Marc Danner, Ted Danson, Don DeLillo, Gerard Depardieu, Junot Diaz, Leonardo DiCaprio, Joan Didion, Maureen Dowd. Jennifer Egan, Daniel Ellsberg, Rahm Emanuel, Nora Ephron, Susan Faludi, Diane Feinstein, Jane Fonda, Barney Frank, Jonathan Franzen, Lady Antonia Fraser, Thomas Friedman, Carlos Fuentes, John Kenneth Galbraith, Andy Garcia, Jerry Garcia, Robert Gates, Newt Gingrich, Allen Ginsberg, Malcolm Gladwell, Danny Glover, Jane Goodall, Stephen Greenblatt, Matt Groening, Sammy Hagar, Woody Harrelson, Robert Hass, Werner Herzog, Christopher Hitchens, Nick Hornby, Khaled Hosseini, Patricia Ireland, Kazuo Ishiguro, Molly Ivins, Jesse Jackson, PD James, Bill T. Jones, James Earl Jones, Ashley Judd, Pauline Kael, John Kerry, Tracy Kidder, Barbara Kingsolver, Alonzo King, Galway Kinnell, Ertha Kitt, Paul Krugman, Ray -

HAMMER Exhibitions

UCLA HAMMER MUSEUM Non Profit US Postage Summer 200 3 PAID Los Angeles Permit 202 MUSEUM INFORMATION Admi ssion $5 Adults; $ 3 Seniors (65+) and UCLA ·Al umni Associationm embers with ID; Free Museum members, UCLA faculty/ staff, Students with I.D. and visitors 17 and under. Free Thursdays for all visitors. Summer Hou rs Tuesday, Saturday and Sunday 12 - 7 pm; Wednesday, Thursday and Friday 12 - 9 pm Closed Mondays, July 4t h, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years Day. Tours Groups of ten or more are by appointment only. Adult groups with reservations receive a discounted ad mission of S3 per person. Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden group tours available upon request. For reservations, call (310) 443-7041. Museum Par king Parking is available under the Museum. Discounted parking with Museum stamp is $2.75 for the first three hours plus $1.50 for each additional 20 minutes. S3 flat rate per entry after 6:30 pm on Thursday. 6. Parking is available on levels Pl and P3. Occidental Petroleum Corporation has par tially endowed the Museum and construct ed the Occidental Petroleum Cultural Center Building, which houses the Museum. Cover image: Ch ristian Marclay,Guitar Drag, 2000, video. Courtesy the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, NY. 10899 Wils hire Boule va rd L os Angel e s, Califo rn ia 900 24 USA For additional program information: VOICE: (310) 443-7000ITT: (310) 443-7094 Website: www.hammer.ucla.edu - HAMMER Eunice and Hal David Collection Gift turing Barbara Ehrenreich with Julianna Malveaux and The world-famous lyricist Hal David and his wife Eunice Suzan-Lori Parks with Todd Boyd. -

Dragon Magazine

Blastoff! The STAR FRONTIERS™ game pro- The STAR FRONTIERS set includes: The work ject was ambitious from the start. The A 16-page Basic Game rule book problems that appear when designing A 64-page Expanded Game rule three complete and detailed alien cul- book tures, a huge frontier area, futuristic is done — A 32-page introductory module, equipment and weapons, and the game Crash on Volturnus rules that make all these elements work now comes 2 full-color maps, 23” x 35” together, were impossible to predict and 10¾" by 17" and not easy to overcome. But the dif- A sheet of 285 full-color counters the fun ficulties were resolved, and the result is a game that lets players enter a truly wide-open space society and explore, The races wander, fight, trade, or adventure A quartet of intelligent, starfaring by Steve Winter through it in the best science-fiction races inhabit the STAR FRONTIERS tradition. rules. New player characters can be D RAGON 7 members of any one of these groups: The adventure ple who had never played a wargame or a Humans (basically just like you With the frontier as its background, role-playing game before. In order to tap and me) the action in a STAR FRONTIERS game this huge market, TSR decided to re- Vrusk (insect-like creatures with focuses on exploring new worlds, dis- structure the STAR FRONTIERS game 10 limbs) covering alien secrets or unearthing an- so it would appeal to people who had Yazirians (ape-like humanoids cient cultures. The rule book includes never seen this type of game. -

Elliott Reid, Sleuth in 'Gentlemen Prefer

Grisham's 'Time to Kill' Coming to Broadway - NYTimes.com JUNE 25, 2013, 3:46 PM Grisham’s ‘Time to Kill’ Coming to Broadway By PATRICK HEALY A stage adaptation of “A Time to Kill,” John Grisham’s legal thriller about a young white lawyer defending a black man for a revenge murder in Mississippi, will open on Broadway in the fall, the producers said on Tuesday. The play is the first adaptation of a novel by the best-selling Mr. Grisham for the theater; the writer is Rupert Holmes, a Tony Award winner for best book and best score for “The Mystery of Edwin Drood.” The novel was made into a 1996 film starring Matthew McConaughey and Samuel L. Jackson. The play’s producers, Daryl Roth and Eva Price, have indicated in investment documents that the show will cost $3.6 million on Broadway. Casting will be announced soon; in the premiere of the play in 2011 at Arena Stage in Washington, Sebastian Arcelus (“Elf”) played the lawyer. That production received mixed reviews. The play is to begin preview performances on Sept. 28 at the Golden Theater and open on Oct. 20. The director will be Ethan McSweeny (the 2000 Broadway revival of “Gore Vidal’s The Best Man”), who staged the play at Arena. http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/25/grishams-time-to-kill-coming-to-broadway/?pagewanted=print[6/26/2013 9:51:02 AM] Escaping a Broken Marriage in a Ruined Town - The New York Times June 25, 2013 THEATER REVIEW Escaping a Broken Marriage in a Ruined Town By CATHERINE RAMPELL If you describe the plot of “Rantoul and Die” to a friend, as I did, you will probably find yourself muttering, “but it’s still really funny, I swear.” And really, I swear, this tale of a sour, violent marriage is funny — darkly, darkly funny. -

Looting the Dungeon: the Quest for the Genre Fantasy Mega-Text

Looting the Dungeon: The Quest for the Genre Fantasy Mega-Text Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Aidan-Paul Canavan. April 2011 Aidan-Paul Canavan University of Liverpool Abstract Popular genre fantasy diverges in a number of significant ways from Tolkien’s mythic vision of fantasy. As a result of the genre’s evolution away from this mythic model, many of the critical approaches used to analyse genre fantasy, often developed from an understanding of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, do not identify new norms and developments. The RPG, a commercial codification of perceived genre norms, highlights specific trends and developments within the genre. It articulates, explains and illustrates core conventions of the genre as they have developed over the last thirty years. Understanding the evolution of the genre is predicated on a knowledge of how the genre is constructed. Assuming the primacy of Tolkien’s text and ignoring how the genre has changed from a literary extension of myth and legend to a market-driven publishing category, reduces the applicability of our analytical models and creates a distorted perception of the genre. This thesis seeks to place the RPG, and its related fictions, at the centre of the genre by recognising their symbiotic relationship with the wider genre of fantasy. By acting as both an articulation of perceived genre norms, and also as a point of dissemination and propagation of these conventions, the RPG is essential to the understanding of fantasy as a genre. -

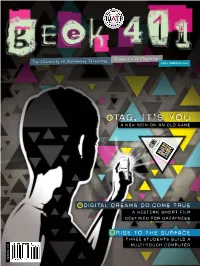

TAG, It's You! a NEW SPIN on an OLD GAME

Student Life Magazine The University of Advancing Technology Issue 5 SUMMER/FALL 2009 03 TAG, IT’S YOU A New Spin on an Old Game S N A P I T 50 D IGITAL DREAMS DO COME TRUE a Western Short FILM Destined for Greatness 24 Rise to The Surface Three Students Build a Multi-Touch Computer $6.95 SUMMER/FALL T.O.C. • • • LOOK FOR THESE MICROSOFT TAGS 04 TAG, IT'S YOU! A NEW SPIN ON AN OLD GAME TA B L E O F CON T E N T S GEEK 411 ISSUE 5 SUMMER/FALL 2009 ABOUT UAT 10 WE’RE TAKING OVER THE WORLD. JOIN US. 32 GET GEEKALICIOUS: T-SHIRT SALE 41 THE BRICKS (OUR AWESOME FACULTY) 49 THE MORTAR (OUR AWESOME STAFF) INSIDE THE TECH WORLD FEATURE 6 BIG BRAIN EVENTS STORIES 26 DEADLY TALENTED ALUMNI 35 WHAT'S YOUR GEEK IQ? 36 GO PLAY WITH YOUR DOTS 24 RISE TO THE SURFACE 38 WHAT’S HOT, WHAT’S NOT ThE RE STUDENTS BUILD A MULTI-TOUCH COMPUTER 42 DAYS OF FUTURE PAST 45 GADGETS & GIZMOS GEEK ESSENTIALS 12 GEEKS ON TOUR 18 DAY IN THE LIFE OF A DORM GEEK 30 LET THE TECH GAMES BEGIN 40 YOU KNOW YOU WANT THIS 46 HOW WE GOT SO AWESOME 47 WE GOT WHAT YOU NEED 22 GEEKILY EVER AFTER 54 GEEKS UNITE – CLUBS AND GROUPS HWTOO W UAT STUDENTS FELL IN LOVE AT FIRST SHOT STORIES ABOUT REALLY SMART PEOPLE 8 INVASION OF THE STAY PUFT BUNNY 29 RAY KURZWEIL 34 GEEK BLOGS 50 COWBOY DREAMS 20 DAVID WESSMAN IS THE MAN UAP T ROFESSOR DIRECTS FILM 16 LIVING THE GEEK DREAM 33 INTRODUCING… NEW GEEKS 14 WE DO STUFF THAT MATTERS 2 | GEEK 411 | UAT STUDENT LIFE MAGAZINE 09UT A 151 © CONTENTS COPYRIGHT BY FABCOM 20092008 LOOK FOR THESE MICROSOFT TAGS THROUGHOUT THIS S ISSUE OF GEEK 411 N AND TAG THEM A P TO GET MORE OF I THE STORY OR T BONUS CONTENT.