Review 330 Fall 2019 SFRA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connotations 14-01

Volume 14, Issue 1 February/March ConNotations 2004 The Bi-Monthly Science Fiction, Fantasy & Convention Newszine of the Central Arizona Speculative Fiction Society April Kicks Off with Ursula K Le Featured Inside Guin, Timothy Zahn, Phoenix SF Tube Talk Special Features ComicCon and World Horror All the latest news about Ursala K LeGuin by Lee Whiteside Scienc Fiction TV shows and other April Events by Lee Whiteside By Lee Whiteside The Arizona Book Festival on Saturday, outreach/scifisymp.html and http:// April 3rd, will feature authors Ursula K. Le www.asu.edu/english/events/outreach/ 24 Frames Jinxed, Hexed, or Cursed: Guin, Alan Dean Foster, and Diana leguin.html All the latest Movie News How I Ruined Harlan Ellison’s Gabaldon on the main stage with CASFS The next day is the Seventh Annual by Lee Whiteside Return to Arizona, Part 2 bringing in Timothy Zahn and other local Arizona Book Festival being held from 10 By Shane Shellenbarger authors for autographing and a special am to 5 pm at the Carnegie Center at 1100 Pro Notes block of programming. LeGuin will also be W. Washingtion in central Phoenix. The Waldorf Conference: appearing at ASU on Friday, April 2nd. Featured authors at the book festival are News about locl genre authors and fans Microphones, scripts, and actors The ASU Department of English Ron Carlson, Nancy Farmer, Alan Dean By Shane Shellenbarger Outreach will be hosting two events on Foster, Diana Gabaldon, Ursula K. Le Musical Notes Friday, April 2nd with Ursula K. LeGuin. Guin, Tom McGuane, and U.S. Supreme In Memorium First will be a daylong Symposium on the Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

The (Im)Possibility of Adaptation in Alex Garland's Annihilation

The (Im)Possibility of Adaptation in Alex Garland’s Annihilation Emmanuelle Ben Hadj A 2018 article about Alex Garland’s science-fiction film Annihilation (2018) asks the question: “is Annihilation the first true film of the Anthropocene?”1 The answer is most likely no. The Anthropocene is a term created in 2000 by scientists Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer to signify the importance of environmental change caused by humans. For decades, and even centuries, humanity has become a geological agent capable of reshaping planet Earth according to their own needs and desires. Our actions have altered the planet’s climate for the worse to the point of hindering the natural course of evolution. For this reason, scientists—though disagreements within the scientific community still exist—have felt the need to suggest the existence of a new geological era, the Anthropocene, that would follow the previous era of the Holocene. Selmin Kara coined the term “Anthropocenema” to talk about the trend of science fiction and other genre films depicting the consequences of anthropogenic actions on Earth.2 I would argue that it would be unfair to call Annihilation the first true film of the Anthropocene when the science fiction genre has been so prolific in tackling environmental disasters, with recent films such as Interstellar (Nolan, 2014), or older films like Andreï Tarkovski’s Stalker (1979) to which Annihilation is often compared. However, Alex Garland’s film certainly stands out in its refusal to compromise with humanity’s fate, hence its particularly negative and pessimistic representation of man. The new ecology of cinema that no longer hesitates to feature human-made disasters, as well as the creation of fictional alternate worlds for pleasure and escapism, could be read as a way to 1 Lewis Gordon, “Is Annihilation the First True Film of the Anthropocene?”, Little White Lies, March 13, 2018 (accessed January 23, 2020). -

Congratulations Susan & Joost Ueffing!

CONGRATULATIONS SUSAN & JOOST UEFFING! The Staff of the CQ would like to congratulate Jaguar CO Susan and STARFLEET Chief of Operations Joost Ueffi ng on their September wedding! 1 2 5 The beautiful ceremony was performed OCT/NOV in Kingsport, Tennessee on September 2004 18th, with many of the couple’s “extended Fleet family” in attendance! Left: The smiling faces of all the STARFLEET members celebrating the Fugate-Ueffi ng wedding. Photo submitted by Wade Olsen. Additional photos on back cover. R4 SUMMIT LIVES IT UP IN LAS VEGAS! Right: Saturday evening banquet highlight — commissioning the USS Gallant NCC 4890. (l-r): Jerry Tien (Chief, STARFLEET Shuttle Ops), Ed Nowlin (R4 RC), Chrissy Killian (Vice Chief, Fleet Ops), Larry Barnes (Gallant CO) and Joe Martin (Gallant XO). Photo submitted by Wendy Fillmore. - Story on p. 3 WHAT IS THE “RODDENBERRY EFFECT”? “Gene Roddenberry’s dream affects different people in different ways, and inspires different thoughts... that’s the Roddenberry Effect, and Eugene Roddenberry, Jr., Gene’s son and co-founder of Roddenberry Productions, wants to capture his father’s spirit — and how it has touched fans around the world — in a book of photographs.” - For more info, read Mark H. Anbinder’s VCS report on p. 7 USPS 017-671 125 125 Table Of Contents............................2 STARFLEET Communiqué After Action Report: R4 Conference..3 Volume I, No. 125 Spies By Night: a SF Novel.............4 A Letter to the Fleet........................4 Published by: Borg Assimilator Media Day..............5 STARFLEET, The International Mystic Realms Fantasy Festival.......6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. -

Read 2021 Book Lists

August - Science Fiction & Fantasy - Read 2021 Fiction Fiction Baker.M Borderline Mishell Baker Fiction Cho.Z Sorcerer to the Crown Zen Cho Fiction Ghosh.A The Calcutta Chromosome Amitav Ghosh Fiction Hopki.N The Salt Roads Nalo Hopkinson Fiction Jones.S Mapping the Interior Stephen Graham Jones Fiction Laval.V The Ballad of Black Tom Victor D. LaValle Fiction Moren.S Certain Dark Things Silvia Moreno-Garcia Fiction Moren.S Signal to Noise Silvia Moreno-Garcia Fiction Okri.B The Freedom Artist Ben Okri Fiction Older.D Half-Resurrection Blues Daniel Jose Older Science Fiction Science Fiction Ahmed.S Throne of the Crescent Moon Saladin Ahmed Paperbk Science Fiction Bodar.A Master of the House of Darts Aliette de Bodard Science Fiction Bodar.A The House of Shattered Wings Aliette de Bodard Science Fiction Bodar.A Servant of the Underworld Aliette de Bodard Science Fiction Bodar.A Seven of Infinities Aliette de Bodard Science Fiction Butle.O Kindred Octavia Butler Science Fiction Calle.K Queen of the Conquered Kacen Callender Science Fiction Chakr.S The Kingdom of Copper S.A. Chakraborty Science Fiction Chamb.B The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet Becky Chambers Science Fiction Cipri.N Finna Nino Cipri Science Fiction Clark.P Ring Shout P. Djeli Clark Science Fiction Danie.A Dreadnought April Daniels Science Fiction Delan.S Babel-17 Samuel R. Delany Science Fiction Edwar.K The Last Sun K.D. Edwards Science Fiction Elmoh.A This is How You Lose the Time War Amal El-Mohtar Science Fiction Gaile.S Magic for Liars Sarah Gailey Science Fiction Gaile.S River of Teeth Sarah Gailey Science Fiction Gratt.T The Queens of Innis Lear Tessa Gratton Science Fiction Hende.A The Year of the Witching Alexis Henderson Science Fiction Hopki.N Midnight Robber Nalo Hopkinson Science Fiction Hossa.S The Gurkha and the Lord of Tuesday Saad Hossain Science Fiction Huang.S Burning Roses S.L. -

Download Ebook > Area X: the Southern Reach Trilogy

TIRAUNNRZ3CA » PDF » Area X: The Southern Reach Trilogy: Annihilation; Authority; Acceptance (Hardback) Download eBook AREA X: THE SOUTHERN REACH TRILOGY: ANNIHILATION; AUTHORITY; ACCEPTANCE (HARDBACK) To get Area X: The Southern Reach Trilogy: Annihilation; Authority; Acceptance (Hardback) eBook, make sure you click the button under and save the file or have access to other information that are have conjunction with AREA X: THE SOUTHERN REACH TRILOGY: ANNIHILATION; AUTHORITY; ACCEPTANCE (HARDBACK) ebook. Read PDF Area X: The Southern Reach Trilogy: Annihilation; Authority; Acceptance (Hardback) Authored by Jeff Vandermeer Released at 2014 Filesize: 1.07 MB Reviews Certainly, this is actually the greatest job by any author. It is definitely simplified but excitement inside the 50 percent of the book. I am just easily will get a delight of studying a composed pdf. -- Lelia Heidenreich This book is great. it absolutely was writtern really perfectly and beneficial. You may like how the blogger compose this book. -- Pink Haley Very good eBook and valuable one. This is for anyone who statte that there was not a worth reading. You will not truly feel monotony at at any time of your own time (that's what catalogs are for concerning if you question me). -- Ms. Ona Muller TERMS | DMCA 5N1ZLWUYGL6V » Kindle » Area X: The Southern Reach Trilogy: Annihilation; Authority; Acceptance (Hardback) Related Books Weebies Family Halloween Night English Language: English Language British Full Colour The Red Leather Diary: Reclaiming a Life Through the Pages of a Lost Journal (P.S.) Pete's Peculiar Pet Shop: The Very Smelly Dragon (Gold A) Abraham Lincoln for Kids: His Life and Times with 21 Activities The First Epistle of H. -

The Predator Script

THE PREDATOR by Shane Black & Fred Dekker Based on the characters created by Jim Thomas & John Thomas REVISED DRAFT 04-17-2016 SPACE Cold. Silent. A billion twinkling stars. Then... A bass RUMBLE rises. Becomes a BONE-RATTLING ROAR as -- A SPACECRAFT RACHETS PAST CAMERA, fuel cables WHIPPING into frame, torn loose! Titanium SCREAMS as the ship DETACHES VIOLENTLY; shards CASCADING in zero gravity--! (NOTE: For reasons that will become apparent, we let us call this vessel “THE ARK.”) WIDER - THE ARK as it HURTLES AWAY from a docking gantry underneath a vastly LARGER SHIP it was attached to. Wobbly. Desperate. We’re witnessing a HIJACK. WIDER STILL - THE PREDATOR MOTHER SHIP DWARFS the escaping vessel. Looming; like a nautilus of molded black steel. INT. PREDATOR MOTHER SHIP Backed by the glow of compu-screens, a half-glimpsed alien -- A PREDATOR -- watches the receding ARK through a viewport. (NOTE: we see him mostly in shadow, full reveal to come). INT. SMALLER VESSEL (ARK) Emergency lights illuminate a dank, organic-looking interior. CAMERA MOVES PAST: EIGHT STASIS CYLINDERS Around the periphery. FROST clouds the cryotubes, prevents us from seeing the “passengers.” Finally, CAMERA ARRIVES AT -- A HULKING, DREAD-LOCKED FIGURE The pilot of this crippled ship. We do not see him fully either, but for the record? This is our “GOOD” PREDATOR.” HIS TALONS dance across a control panel; a shrill beep..! Predator symbols, but we get the idea: ERROR--ERROR--ERROR-- Our Predator TAPS more controls. Feverish. Until -- EXT. ARK A final tether COMES LOOSE, venting PLASMA energy, and -- 2. -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

Dragon Magazine

Blastoff! The STAR FRONTIERS™ game pro- The STAR FRONTIERS set includes: The work ject was ambitious from the start. The A 16-page Basic Game rule book problems that appear when designing A 64-page Expanded Game rule three complete and detailed alien cul- book tures, a huge frontier area, futuristic is done — A 32-page introductory module, equipment and weapons, and the game Crash on Volturnus rules that make all these elements work now comes 2 full-color maps, 23” x 35” together, were impossible to predict and 10¾" by 17" and not easy to overcome. But the dif- A sheet of 285 full-color counters the fun ficulties were resolved, and the result is a game that lets players enter a truly wide-open space society and explore, The races wander, fight, trade, or adventure A quartet of intelligent, starfaring by Steve Winter through it in the best science-fiction races inhabit the STAR FRONTIERS tradition. rules. New player characters can be D RAGON 7 members of any one of these groups: The adventure ple who had never played a wargame or a Humans (basically just like you With the frontier as its background, role-playing game before. In order to tap and me) the action in a STAR FRONTIERS game this huge market, TSR decided to re- Vrusk (insect-like creatures with focuses on exploring new worlds, dis- structure the STAR FRONTIERS game 10 limbs) covering alien secrets or unearthing an- so it would appeal to people who had Yazirians (ape-like humanoids cient cultures. The rule book includes never seen this type of game. -

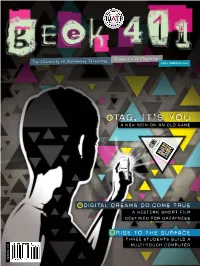

TAG, It's You! a NEW SPIN on an OLD GAME

Student Life Magazine The University of Advancing Technology Issue 5 SUMMER/FALL 2009 03 TAG, IT’S YOU A New Spin on an Old Game S N A P I T 50 D IGITAL DREAMS DO COME TRUE a Western Short FILM Destined for Greatness 24 Rise to The Surface Three Students Build a Multi-Touch Computer $6.95 SUMMER/FALL T.O.C. • • • LOOK FOR THESE MICROSOFT TAGS 04 TAG, IT'S YOU! A NEW SPIN ON AN OLD GAME TA B L E O F CON T E N T S GEEK 411 ISSUE 5 SUMMER/FALL 2009 ABOUT UAT 10 WE’RE TAKING OVER THE WORLD. JOIN US. 32 GET GEEKALICIOUS: T-SHIRT SALE 41 THE BRICKS (OUR AWESOME FACULTY) 49 THE MORTAR (OUR AWESOME STAFF) INSIDE THE TECH WORLD FEATURE 6 BIG BRAIN EVENTS STORIES 26 DEADLY TALENTED ALUMNI 35 WHAT'S YOUR GEEK IQ? 36 GO PLAY WITH YOUR DOTS 24 RISE TO THE SURFACE 38 WHAT’S HOT, WHAT’S NOT ThE RE STUDENTS BUILD A MULTI-TOUCH COMPUTER 42 DAYS OF FUTURE PAST 45 GADGETS & GIZMOS GEEK ESSENTIALS 12 GEEKS ON TOUR 18 DAY IN THE LIFE OF A DORM GEEK 30 LET THE TECH GAMES BEGIN 40 YOU KNOW YOU WANT THIS 46 HOW WE GOT SO AWESOME 47 WE GOT WHAT YOU NEED 22 GEEKILY EVER AFTER 54 GEEKS UNITE – CLUBS AND GROUPS HWTOO W UAT STUDENTS FELL IN LOVE AT FIRST SHOT STORIES ABOUT REALLY SMART PEOPLE 8 INVASION OF THE STAY PUFT BUNNY 29 RAY KURZWEIL 34 GEEK BLOGS 50 COWBOY DREAMS 20 DAVID WESSMAN IS THE MAN UAP T ROFESSOR DIRECTS FILM 16 LIVING THE GEEK DREAM 33 INTRODUCING… NEW GEEKS 14 WE DO STUFF THAT MATTERS 2 | GEEK 411 | UAT STUDENT LIFE MAGAZINE 09UT A 151 © CONTENTS COPYRIGHT BY FABCOM 20092008 LOOK FOR THESE MICROSOFT TAGS THROUGHOUT THIS S ISSUE OF GEEK 411 N AND TAG THEM A P TO GET MORE OF I THE STORY OR T BONUS CONTENT. -

PDF UTC Schedule

Flights of Foundry 2021 A Art/Illustration D Audio/Podcasting C Comics F Guest of Honor I Industry Biz L Limited Access P Poetry O Prose T Translation W Writing APRIL 16 • FRIDAY 14:00 – 14:25 W Diane Turnshek - Reading Courtyard Speakers: Diane Turnshek I'll read shorter and shorter fiction as I walk around to different spots in my very small house until I tell my story with a negative word count. Small is beautiful! Happy to welcome you folks to my tiny house tour and tiny reading. 15:00 – 15:25 W Gregory Wilson - Reading Courtyard Speakers: Gregory Wilson From my most recent bio--please let me know if you need more information! Gregory A. Wilson is Professor of English at St. John's University in New York City, where he teaches creative writing, speculative fiction, and various other courses in literature. In addition to academic work, he is the author of the epic fantasy The Third Sign, the graphic novel Icarus, the dark fantasy Grayshade, and the D&D adventure/sourcebook Tales and Tomes from the Forbidden Library. He also has short stories in a number of anthologies, and has several projects forthcoming in 2021. He co- hosts the critically acclaimed actual play Speculate! The Podcast for Writers, Readers, and Fans (speculatesf.com) podcast, is a member of the Gen Con Writers' Symposium and co-coordinator of the Origins Library, and is a regular panelist at conferences nationally and internationally. He is the lead vocalist and trumpet player for The Road, a long running progressive rock band with three albums to its credit, and is the lead writer for Chosen Heart, a video game currently in production. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Crafting Women’s Narratives The Material Impact of Twenty-First Century Romance Fiction on Contemporary Steampunk Dress Shannon Marie Rollins A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Art) at The University of Edinburgh Edinburgh College of Art, School of Art September 2019 Rollins i ABSTRACT Science fiction author K.W. Jeter coined the term ‘steampunk’ in his 1987 letter to the editor of Locus magazine, using it to encompass the burgeoning literary trend of madcap ‘gonzo’-historical Victorian adventure novels. Since this watershed moment, steampunk has outgrown its original context to become a multimedia field of production including art, fashion, Do-It-Yourself projects, role-playing games, film, case-modified technology, convention culture, and cosplay alongside science fiction. And as steampunk creativity diversifies, the link between its material cultures and fiction becomes more nuanced; where the subculture began as an extension of the text in the 1990s, now it is the culture that redefines the fiction.