How the Canadian-Built EMD Class 66 Completely Changed the Face of British Railfreight by Thomas Blampied and Dave Kirwin - (January 2010)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17 November 2006 Issue 62

ISSN 1751-8091 RailwayThe Herald 17 November 2006 Issue 62 TheThe complimentarycomplimentary UKUK railwayrailway journaljournal forfor thethe railwayrailway enthusiastenthusiast For the latest issue and copies of all back issues, visit www.railwayherald.com RailwayThe Herald Issue 62 Front Cover On the Bluebell Railway, ex-LBSCR 0-6-0T 'Terrier' No 362 Martello exits Sharpthorne tunnel with a photographer's charter on 14 November. The loco is currently visiting the line from Bressingham. Chris Nevard Contents Northern Rail unveils new look to refurbished Class 155s Page 3 Eurostar's move to St. Pancras less than 12 months away. Page 4 Redevelopment work takes shape at Southampton Central station. Page 7 Regular Sections Classified Advertisements 5 Rolling Stock News 7 Railtour News 8 Notable Workings Pictorial 10 ABOVE: The Fifty Fund's Class 50s stood in for the non-availability of a pair of EWS Class 37s to work the Cardiff - Preservation View 13 Gloucester shuttles in connection with last weekends's England vs Argentina Rugby International match. Here, No. 50031 Product Reviews 15 Hood approaches Magor with classmate No. 50049 Defiance on the rear, with a Gloucester bound train. Don Gatehouse Submission Guidelines In response to the constantly Princess Elizabeth recreates record run on WCML increasing number of digital Ex-LMS 'Princess Royal' commencing at Preston. 38 seconds. photographic submissions, Class No. 6201 Princess The train commemorated Railway Herald will have Railway Herald has compiled a Elizabeth worked a special the record run carried out a full in-depth behind-the- 'Submissions Guidelines' document, two-day charter on 16/17 70 years ago when No. -

Bring the Country Together

Annual Return 2008 Delivering for you Network Rail helps bring the country together. We own, operate and maintain Britain’s rail network, increasingly delivering improved standards of safety, reliability and efficiency. Our investment programme to enhance and modernise the network is the most ambitious it has ever been. Delivering a 21st century railway for our customers and society at large. Every day. Everywhere. Contents Executive summary 1 Switches and crossings renewed (M25) 117 Introduction 9 Signalling renewed (M24) 119 Targets 13 Bridge renewals and remediation (M23) 122 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) 16 Culverts renewals and remediation (M26) 123 Retaining walls remediation (M27) 124 Section 1 – Operational performance and stakeholder Earthwork remediation (M28) 125 relationships 18 Tunnel remediation (M29) 126 Public Performance Measure (PPM) 19 Composite activity volumes measure 127 Summarised network-wide data (delays to major operators) 20 National data by delay category grouping 25 Section 5 – Safety and environment 129 Results for operating routes by delay category 31 Workforce safety 129 Asset failure 40 System Safety Infrastructure wrong side failures 131 Customer satisfaction – passenger and freight operators 46 Level crossing misuse 132 Supplier satisfaction 47 Signals Passed At Danger (SPADs) 133 Doing business with Network Rail 48 Operating irregularities 135 Joint Performance Process 48 Criminal damage 136 Route Utilisation Strategies (RUSs) 52 Environment 138 Regulatory enforcement 53 Safety and environment enhancements -

Fastline Simulation

(PRIVATE and not for Publication) F.S. 07131/5 fastline simulation FREIGHT STOCK PACK 03 VEA VANS INSTRUCTIONS FOR INSTALLATION AND USE OF A ROLLING STOCK PACK FOR TRAIN SIMULATOR 2015 This book is for the use of customers, and supersedes as from 13th July 2015, all previous instructions on the installation and use of the above rolling stock pack. THORNTON I. P. FREELY 13th July, 2015 MOVEMENTS MANAGER 1 ORDER OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 2 Installation ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 2 The Rolling Stock ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 2 File Naming Overview.. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 File name options ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 History of the Rolling Stock ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 Temporary Speed Restrictions. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 6 Scenarios ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 7 Known Issues .. -

Industria Di Marca Distribuzione Moderna

INDUSTRIA DI MARCA | DISTRIBUZIONE MODERNA Mappatura Offerta di Trasporto Ferroviario Novembre 2016 Indice1 ECR Italia .............................................................................................................................. 6 Introduzione .......................................................................................................................... 7 Imprese ferroviarie ................................................................................................................ 8 *Captrain Italia S.r.l. ............................................................................................................................. 8 ChemOil Logistics AG – Filiale Italiana .............................................................................................. 10 Compagnia Ferroviaria Italiana .......................................................................................................... 11 DB Schenker Rail Italia Services S.r.l. ............................................................................................... 12 *ERS Railways B.V. ........................................................................................................................... 13 Nordcargo S.r.l. .................................................................................................................................. 15 Oceanogate Italia S.p.A. .................................................................................................................... 16 Rail Cargo Italia S.r.l. ........................................................................................................................ -

Framework Capacity Statement 2021

OFFICIAL Framework Capacity Statement 2021 Including consultation on alternative approaches to presenting capacity information Network Rail April 2021 Network Rail Framework Capacity Statement April 2021 1 OFFICIAL Contents Framework Capacity Statement Annex: Consultation on alternative approaches 1. Purpose 4. Background to the 2021 consultation 1.1 Purpose 4 4.1 Developments since 2016 17 4.2 Timing and purpose 17 2. Framework capacity on Network Rail’s network 2.1 Infrastructure covered by this statement 7 5. Granularity of analysis – examples and issues 2.2 Framework agreements in Great Britain 9 5.1 Dividing the railway geographically 19 2.3 Capacity allocation 11 5.2 Analysis at Strategic Route level 20 5.3 Analysis at SRS level 23 3. How to identify framework capacity 5.4 Constant Traffic Sections 25 3.1 Capacity of the network 13 3.2 Capacity allocated in framework agreements 13 6. The requirement 3.3 Capacity available for framework agreements 14 6.1 Areas open for interpretation in application 28 3.4 Using the timetable as a proxy 14 6.2 Potential solutions 29 3.5 Conclusion 15 6.3 Questions for stakeholders 30 Network Rail Framework Capacity Statement April 2021 2 OFFICIAL 1. Purpose Network Rail Framework Capacity Statement April 2021 3 OFFICIAL 1.1 Purpose This statement is published alongside Network Rail’s Network current transformation programme, to make the company work Statement in order to meet the requirements of European better with train operators to serve passengers and freight users. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/545 of 7 April 2016 on procedures and criteria concerning framework Due to the nature of framework capacity, which legally must not agreements for the allocation of rail infrastructure capacity. -

5172/10 ADD 1 REV1 GW/Cf 1 DG C I C COUNCIL of THE

COUNCIL OF Brussels, 16 December 2010 THE EUROPEAN UNION 5172/10 ADD 1 REV 1 TRANS 2 COVER NOTE No. Cion doc.: SEC(2009)1687 final/2 Subject: Commission Staff Working Document accompanying document to the report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on monitoring development of the rail market Delegations will find attached a new version of document SEC(2009) 1687 final. ________________________ Encl.: SEC(2009) 1687 final/2 5172/10 ADD 1 REV1 GW/cf 1 DG C I C EN EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 8.12.2010 SEC(2009)1687/2 CORRIGENDUM: This text annuls and replaces SEC(2009) 1687 of 18 December 2009 Concern : mainly the data related to Bulgaria and France, as well as the Annex 3 (overview table of the infringements procedures concerning the 1st Railway Package, as it appears on 8 December 2009), in the only English linguistic version. COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT accompanying document to the REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE COUNCIL AND THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ON MONITORING DEVELOPMENT OF THE RAIL MARKET {COM(2009)676 final/2} EN 1 EN LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AT Austria m million BE Belgium MT Malta BG Bulgaria NO Norway CH Switzerland n.a. not available CS Czechoslovakia NIB National Investigation Body CY Cyprus NL Netherlands CZ Czech Republic NSA National Safety Authority DE Germany p passengers DK Denmark p.a. per annum EC European Community pkm passenger-kilometres ECMT European Conference of Ministers of Transport PL Poland EE Estonia PSO Public Service Obligations EL Greece PT Portugal ES Spain Q quarter EU -

Wickness Models Soundscape Class 66

Wickness Models Soundscape Class 66 Manufacturer: - Wickness Models Project number: - WM066-1S Project version: - SSV1-Farm Class 66 Power type Diesel-electric Builder Electro-Motive Diesel Model JT42CWR or Series 66 Build date 1998–2014 Total produced 446 The Class 66 is a type of six-axle diesel electric freight locomotive developed in part from the British Rail Class 59, for use on the railways of the UK. Since its introduction the class has been successful and has been sold to British and other European railway companies. In Continental Europe it is marketed as the EMD Series 66 (JT42CWR). The initial classification was as Class 61, then they were subsequently given the Class 66 designation in the British classification system (TOPS). In 1998 Freightliner placed an order for locomotives. They were followed by GB Railfreight, and then Direct Rail Services. Although sometimes unpopular with many rail enthusiasts, due to their ubiquity and having caused the displacement of several older types of (mostly) British built locomotives, their high reliability has helped rail freight to remain competitive. Rail enthusiasts call them "sheds". The Electro-Motive Diesel (EMD) Class 66 (or JT42CWR) are Co-Co diesel locomotives built by EMD for the European heavy freight market. Designed for use in Great Britain as the Class 66, a development of the Class 59, they have been adapted and certified for use in other European countries. Outside Europe, 40 locomotives have been sold to Egyptian Railways for passenger operation. A number of locomotives built for Euro Cargo Rail in France with roof- mounted air conditioning are classed Class 77. -

Competition Act 1998

Competition Act 1998 Decision of the Office of Rail Regulation* English Welsh and Scottish Railway Limited Relating to a finding by the Office of Rail Regulation (ORR) of an infringement of the prohibition imposed by section 18 of the Competition Act 1998 (the Act) and Article 82 of the EC Treaty in respect of conduct by English Welsh and Scottish Railway Limited. Introduction 1. This decision relates to conduct by English Welsh and Scottish Railway Limited (EWS) in the carriage of coal by rail in Great Britain. 2. The case results from two complaints. 3. On 1 February 2001 Enron Coal Services Limited (ECSL)1 submitted a complaint to the Director of Fair Trading2. Jointly with ECSL, Freightliner Limited (Freightliner) also, within the same complaint, alleged an infringement of the Chapter II prohibition in respect of a locomotive supply agreement between EWS and General Motors Corporation of the United States (General Motors). Together these are referred to as the Complaint. The Complaint alleges: “[…] that English, Welsh and Scottish Railways Limited (‘EWS’), the dominant supplier of rail freight services in England, Wales and Scotland, has systematically and persistently acted to foreclose, deter or limit Enron Coal Services Limited’s (‘ECSL’) participation in the market for the supply of coal to UK industrial users, particularly in the power sector, to the serious detriment of competition in that market. The complaint concerns abusive conduct on the part of EWS as follows. • Discriminatory pricing as between purchasers of coal rail freight services so as to disadvantage ECSL. *Certain information has been excluded from this document in order to comply with the provisions of section 56 of the Competition Act 1998 (confidentiality and disclosure of information) and the general restrictions on disclosure contained at Part 9 of the Enterprise Act 2002. -

Freight Transport

House of Commons Transport Committee Freight Transport Eighth Report of Session 2007–08 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 9 July 2008 HC 249 Published on 19 July 2008 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £24.50 The Transport Committee The Transport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Transport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mrs Louise Ellman MP (Labour/Co-operative, Liverpool Riverside) (Chairman) Mr David Clelland MP (Labour, Tyne Bridge) Clive Efford MP (Labour, Eltham) Mr Philip Hollobone MP (Conservative, Kettering) Mr John Leech MP (Liberal Democrat, Manchester, Withington) Mr Eric Martlew MP (Labour, Carlisle) Mr Lee Scott MP (Conservative, Ilford North) David Simpson MP (Democratic Unionist, Upper Bann) Mr Graham Stringer MP (Labour, Manchester Blackley) Mr David Wilshire MP (Conservative, Spelthorne) Mrs Gwyneth Dunwoody MP (Labour, Crewe and Nantwich) was also a member of the Committee during the period covered by this report. Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/transcom. Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are Tom Healey (Clerk), Annette Toft (Second Clerk), David Davies (Committee Specialist), Tim Steer (Committee Specialist), Alison Mara (Committee Assistant), Ronnie Jefferson (Secretary), Gaby Henderson (Senior Office Clerk) and Laura Kibby (Media Officer). -

Implications for the Rail Freight Sector of Stricter European Union Locomotive Emission Limits: a UK Perspective

Implications for the rail freight sector of stricter European Union locomotive emission limits: a UK perspective Article Accepted Version Wilde, M. L. (2016) Implications for the rail freight sector of stricter European Union locomotive emission limits: a UK perspective. Business Law Review, 37 (4). pp. 118-123. ISSN 0143-6295 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/66749/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://www.kluwerlawonline.com/abstract.php?area=Journals&id=BULA2016024 Publisher: Kluwer Law International All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Implications for the Rail-freight Sector of Stricter EU Locomotive Emission Limits: a UK perspective INTRODUCTION The European rail freight sector has grown exponentially over the past twenty to thirty years as the limitations of road transport have become increasingly apparent.1 Moreover, moving more freight by rail is seen as a greener alternative.2 Thus, in some respects it is a case of ‘back to the future’ and the halcyon days when the majority of freight was moved by rail; although it must be acknowledged that in the twenty-first century the bulk of freight is still moved by road and this is likely to be the case for the foreseeable future. -

Annex A: Organisations Consulted

Annex A: Organisations consulted This section lists the organisations who have been directly invited to respond to this consultation: Administrative Justice and Tribunals Service Advanced Transport Systems AEA Technology Plc Aggregate Industries Alcan Primary Metal Europe Alcan Smelting & Power UK Alstom Transport Ltd Amey Plc Angel Trains Arriva Trains Wales ASLEF Association of Chief Police Officers in Scotland Association of Community Rail Partnerships Association of London Government Association of Railway Industry Occupational Physicians Association of Train Operating Companies Atkins Rail Avon Valley Rail Axiom Rail BAA Rail Babcock Rail Bala Lake Railways Balfour Beatty plc Bluebell Railway PLC Bombardier Transportation BP Oil UK Ltd Brett Aggregates Ltd British Chambers of Commerce British Gypsum British International Freight Association British Nuclear Fuels Ltd British Nuclear Group Sellafield Ltd British Ports Association British Transport Police BUPA Buxton Lime Industries Ltd c2c Rail Ltd Cabinet Office Campaign for Better Transport Carillion Rail Cawoods of Northern Ireland Cemex UK Cement Ltd Channel Tunnel Safety Authority Chartered Institute of Logistics & Transport Chiltern Railways Company Ltd City of Edinburgh Council Civil Aviation Authority Colas Rail Ltd Commission for Integrated Transport Confederation of British Industry Confederation of Passenger Transport UK Consumer Focus Convention of Scottish Local Authorities Correl Rail Ltd Corus Construction & Industrial CrossCountry Crossrail Croydon Tramlink Dartmoor -

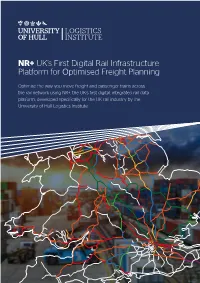

NR+ UK's First Digital Rail Infrastructure Platform for Optimised Freight Planning

LOGISTICS INSTITUTE NR+ UK’s First Digital Rail Infrastructure Platform for Optimised Freight Planning Optimise the way you move freight and passenger trains across the rail network using NR+, the UK’s first digital, integrated rail data platform, developed specifically for the UK rail industry by the University of Hull Logistics Institute. and functionalities for passengerplanning. and functionalities for data willincludeallrelevant ofNR+ conflicts. versions possession Later (RA),electrification engineering availability andpotential gauge, weight, length,route suchasloading criteria basedonkey routes, analyserail to you The applications allow planning. route freight for includesalldatarequired of NR+ version The first theirsolutiondevelopment. thedatafor party tapinto to third any with openAPIsfor database, asingle,integrated into movements planningandschedulingrail for required NR+ University ofHull University Data Sources Database APIs Applications Suite brings together, for the first time, the multiple and diverse information sources sources information the first time,themultipleanddiverse for bringstogether, Suite Tiplocks Infrastrucutre Manager Infrastructure and Schedule Visualisation NESA Implementation Infrastructure Asset API Train Route Planning Initial Possessions BPlan and Conflicts Workflow Load Books Reporting and Analytics Geospatial Data Train Timetabling Development Scheduling API Incident and Delays Future Schedules Management Possessions (EAS) Alerts and Notifications QJ Paths Simulation Development 3rd Party3rd 3rd