A Legacy of Advocacy Is Born As AAI Confronts Mccarthyism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J. Edgar Hoover, "Speech Before the House Committee on Un‐American Activities" (26 March 1947)

Voices of Democracy 3 (2008): 139‐161 Underhill 139 J. EDGAR HOOVER, "SPEECH BEFORE THE HOUSE COMMITTEE ON UN‐AMERICAN ACTIVITIES" (26 MARCH 1947) Stephen Underhill University of Maryland Abstract: J. Edgar Hoover fought domestic communism in the 1940s with illegal investigative methods and by recommending a procedure of guilt by association to HUAC. The debate over illegal surveillance in the 1940s to protect national security reflects the on‐going tensions between national security and civil liberties. This essay explores how in times of national security crises, concerns often exist about civil liberties violations in the United States. Key Words: J. Edgar Hoover, Communism, Liberalism, National Security, Civil Liberties, Partisanship From Woodrow Wilson's use of the Bureau of Investigation (BI) to spy on radicals after World War I to Richard Nixon's use of the renamed Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to spy on U.S. "subversives" during Vietnam, the balance between civil liberties and national security has often been a contentious issue during times of national crisis.1 George W. Bush's use of the National Security Agency (NSA) to monitor the communications of suspected terrorists in the United States is but the latest manifestation of a tension that spans the existence of official intelligence agencies.2 The tumult between national security and civil liberties was also visible during the early years of the Cold War as Republicans and Democrats battled over the U.S. government's appropriate response to the surge of communism internationally. Entering the presidency in 1945, Harry S Truman became privy to the unstable dynamic between Western leaders and Josef Stalin over the post‐war division of Eastern Europe.3 Although only high level officials within the executive branch intimately understood this breakdown, the U.S. -

Administrative National Security

ARTICLES Administrative National Security ELENA CHACHKO* In the past two decades, the United States has applied a growing num- ber of foreign and security measures directly targeting individualsÐ natural or legal persons. These individualized measures have been designed and carried out by administrative agencies. Widespread appli- cation of individual economic sanctions, security watchlists and no-¯y lists, detentions, targeted killings, and action against hackers responsible for cyberattacks have all become signi®cant currencies of U.S. foreign and security policy. Although the application of each of these measures in discrete contexts has been studied, they have yet to attract an inte- grated analysis. This Article examines this phenomenon with two main aims. First, it documents what I call ªadministrative national securityº: the growing individualization of U.S. foreign and security policy, the administrative mechanisms that have facilitated it, and the judicial response to these mechanisms. Administrative national security encompasses several types of individualized measures that agencies now apply on a routine, inde®- nite basis through the exercise of considerable discretion within a broad framework established by Congress or the President. It is therefore best understood as an emerging practice of administrative adjudication in the foreign and security space. Second, this Article considers how administrative national security integrates with the presidency and the courts. Accounting for administra- tive national security illuminates the President's constitutional role as chief executive and commander-in-chief and his control of key aspects of * Lecturer on Law, Harvard Law School (Fall 2019); Post-doctoral Fellow, Perry World House, University of Pennsylvania; S.J.D. Candidate, Harvard Law School; LL.B., Hebrew University of Jerusalem (2014). -

Legal Minds Debate Whether Obama Executive Order on Abortion Will Stick

Legal minds debate whether Obama executive order on abortion will stick WASHINGTON – One of the biggest questions remaining as implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act begins is whether the executive order on abortion funding signed by President Barack Obama will be effective in stopping any expanded use of taxpayer funds for abortion. Legal experts and members of Congress disagree about the impact of the president’s March 24 Executive Order 13535, “Ensuring Enforcement and Implementation of Abortion Restrictions in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.” Anthony Picarello, general counsel for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, and Michael Moses, associate general counsel, said in a nine-page legal analysis that the executive order is likely to face court challenges and does not resolve problems on abortion funding and conscience protection in the health reform law. “Where the order purports to fix a shortcoming of the act in these areas, it is highly likely to be legally invalid; and where the order is highly likely to be legally valid, it does nothing to fix those shortcomings,” they said. Rep. Bart Stupak, D-Mich., a key player in the health reform debate, said executive orders “have been important means of implementing public policy” throughout history, noting that President George W. Bush used Executive Order 13435 in 2007 to limit the use of federal funds for embryonic stem-cell research. “This executive order followed the principle of the sanctity of life, and was applauded and welcomed by the pro-life community,” said Stupak, a nine-term House member who recently announced that he would not run for re-election. -

Letter from Senator Joseph Mccarthy to the President of the United States

Letter from Senator Joseph McCarthy to the President of the United States This letter from Senator Joseph McCarthy, Republican representative of Wisconsin, to President Harry Truman was written three days after McCarthy’s famous Wheeling Speech. This speech signaled McCarthy’s rise to influence, as he gained national attention by producing a piece of paper on which he claimed he had listed the names of 205 members of the Communist Party working secretly in the U.S. State Department. McCarthy was, at the time of this letter, beginning to exploit national concerns about Communist infiltration during the Cold War. This fear of infiltration was intensified by the Soviet Union’s recent development of the atomic bomb and the coming Communist takeover of China. “McCarthyism” however was not yet at its peak. Senator McCarthy here at first encourages President Truman to commit more resources to the war of containment being fought in South Korea, and secondly questioned the legitimacy and effectiveness of Truman’s loyalty program, signed into effect by Executive Order 9835 in 1947. This program required the FBI to run checks on almost anyone involved in the U.S. government and subsequently to launch investigations into any government employee with what could be presumed as questionable political associations. The Loyalty Program was not enough to satisfy Senator McCarthy, who suspected that a number of subversives had slipped through the investigation and remained in the State Department. President Truman made it clear that he would not take McCarthy’s accusations seriously and that the Senator was “the best asset the Kremlin has.”109 July 12, 1950 The President The White House Washington, D. -

Loyalty Among Government Employees

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 58 DECE-MBER, 1948 Nu-.mnB 1 LOYALTY AMONG GOVERNMENT EMPLOYEES THOMAS I. EMERSON* DAVID M. HELFELD t I. BACKGROUNM MOUNTING tensions in our society have brought us to a critical point in the matter of political and civil rights. The stresses are in large measure internal. They grow out of the accelerating movement to effect far-reaching changes in our economic and social structure, a movement which evokes ever-increasing resistance. As the conflicts sharpen, there is rising pressure to discard or undermine the basic principles embodied in the democratic concept of freedom for political opposition. Maintenance of free institutions in a period of deepening crisis would be difficult enough if the struggle were confined to our shores. But the domestic problem is only an element of the world problem. Large areas of the world have abandoned the system of capitalism in favor of socialism. Other areas are far advanced in economic and social change. Everywhere there is struggle, uncertainty, fear and confusion. Pro- tagonists of the more militant economic and social philosophies are organized into political parties which have their offshoots and counter- parts in other countries, including our owm. As a result, the preserva- tion of political freedom, the right to hold and express opinions di- verging from the opinion of the majority, is often made to appear incompatible with the overriding requirements of "loyalty," "patri- otism," "national security" and the like. The danger of "foreign id- eologies," "infiltration," "subversion" and "espionage" are invoked to justify the suspension of traditional rights and freedoms. -

Fortress of Liberty: the Rise and Fall of the Draft and the Remaking of American Law

Fortress of Liberty: The Rise and Fall of the Draft and the Remaking of American Law Jeremy K. Kessler∗ Introduction: Civil Liberty in a Conscripted Age Between 1917 and 1973, the United States fought its wars with drafted soldiers. These conscript wars were also, however, civil libertarian wars. Waged against the “militaristic” or “totalitarian” enemies of civil liberty, each war embodied expanding notions of individual freedom in its execution. At the moment of their country’s rise to global dominance, American citizens accepted conscription as a fact of life. But they also embraced civil liberties law – the protections of freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly, and procedural due process – as the distinguishing feature of American society, and the ultimate justification for American military power. Fortress of Liberty tries to make sense of this puzzling synthesis of mass coercion and individual freedom that once defined American law and politics. It also argues that the collapse of that synthesis during the Cold War continues to haunt our contemporary legal order. Chapter 1: The World War I Draft Chapter One identifies the WWI draft as a civil libertarian institution – a legal and political apparatus that not only constrained but created new forms of expressive freedom. Several progressive War Department officials were also early civil libertarian innovators, and they built a system of conscientious objection that allowed for the expression of individual difference and dissent within the draft. These officials, including future Supreme Court Justices Felix Frankfurter and Harlan Fiske Stone, believed that a powerful, centralized government was essential to the creation of a civil libertarian nation – a nation shaped and strengthened by its diverse, engaged citizenry. -

The University of Utah and James EP Toman

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-2015 Hunting for a Witch to Burn: The University of Utah and James E. P. Toman Joseph Lanning Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Recommended Citation Lanning, Joseph, "Hunting for a Witch to Burn: The University of Utah and James E. P. Toman" (2015). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 520. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/520 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hunting for a Witch to Burn: The University of Utah and James E. P. Toman by Joseph Lanning A Plan-B paper proposal submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in History Approved: _____________________________ _____________________________ Colleen O'Neill Victoria Grieve Major Professor Committee Member _____________________________ Matthew LaPlante Committee Member UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2015 1 The University of California (UC) and its notorious 1949 loyalty oath scandal may be the most popular and widely discussed case study of post-WWII political repression within American universities, but it was not the first casualty. That "honor" goes to the University of Washington (UW) in 1946, a year before President Truman enacted Executive Order 9835 requiring federal employees to sign oaths of loyalty to the US Constitution. -

Sexual Orientation and the Federal Workplace

SEXUAL ORIENTATION and the FEDERAL WORKPLACE Policy and Perception A Report to the President and Congress of the United States by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board MAY 2014 THE CHAIRMAN U.S. MERIT SYSTEMS PROTECTION BOARD 1615 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20419-0001 The President President of the Senate Speaker of the House of Representatives Dear Sirs: In accordance with the requirements of 5 U.S.C. § 1204(a)(3), it is my honor to submit this U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) report, Sexual Orientation and the Federal Workplace: Policy and Perception. The purpose of our study was to examine Federal employee perceptions of workplace treatment based on sexual orientation, review how Federal workplace protections from sexual orientation discrimination evolved, and determine if further action is warranted to communicate or clarify those protections. Since 1980, the U.S. Office of Personnel Management has interpreted the tenth Prohibited Personnel Practice (5 U.S.C. § 2302(b)(10)), which bars discrimination in Federal personnel actions based on conduct that does not adversely affect job performance, to prohibit sexual orientation discrimination. As this prohibition has neither been specifically expressed in statute nor affirmed in judicial decision, it has been subject to alternate interpretations. Executive Order 13087 prohibited sexual orientation discrimination in Federal employment but provided no enforceable rights or remedies for Federal employees who allege they are the victims of sexual orientation discrimination. Any ambiguity in the longstanding policy prohibiting sexual orientation discrimination in the Federal workplace would be resolved by legislation making that prohibition explicit. Such legislation could grant Federal employees who allege they are victims of sexual orientation discrimination access to the same remedies as those who allege discrimination on other bases. -

Civillibertieshstlookinside.Pdf

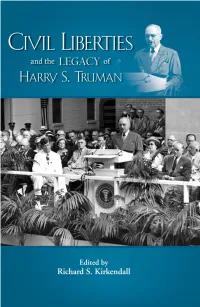

Civil Liberties and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman The Truman Legacy Series, Volume 9 Based on the Ninth Truman Legacy Symposium The Civil Liberties Legacy of Harry S. Truman May 2011 Key West, Florida Edited by Richard S. Kirkendall Civil Liberties and the LEGACY of Harry S. Truman Edited by Richard S. Kirkendall Volume 9 Truman State University Press Copyright © 2013 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover photo: President Truman delivers a speech on civil liberties to the American Legion, August 14, 1951 (Photo by Acme, copy in Truman Library collection, HSTL 76- 332). All reasonable attempts have been made to locate the copyright holder of the cover photo. If you believe you are the copyright holder of this photograph, please contact the publisher. Cover design: Teresa Wheeler Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Civil liberties and the legacy of Harry S. Truman / edited by Richard S. Kirkendall. pages cm. — (Truman legacy series ; 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61248-084-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-61248-085-5 (ebook) 1. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Political and social views. 2. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Influence. 3. Civil rights—United States—History—20th century. 4. United States. Constitution. 1st–10th Amendments. 5. Cold War—Political aspects—United States. 6. Anti-communist movements—United States— History—20th century. 7. United States—Politics and government—1945–1953. I. Kirkendall, Richard Stewart, 1928– E814.C53 2013 973.918092—dc23 2012039360 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher. -

Victims of the Mccarthy Era, in Support of Humanitarian Law Project, Et Al

Nos. 08-1498 and 09-89 ERIC H. HOLDER, JR., ATTORNEY GENERAL, ET AL., Petitioners, v. HUMANITARIAN LAW PROJECT, ET AL., Respondents. HUMANITARIAN LAW PROJECT, ET AL., Cross-Petitioners, v. ERIC H. HOLDER, JR., ATTORNEY GENERAL, ET AL., Respondents. ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE VICTIMS OF THE MCCARTHY ERA, IN SUPPORT OF HUMANITARIAN LAW PROJECT, ET AL. Stephen F. Rohde John A. Freedman Rohde & Victoroff (Counsel of Record) 1880 Century Park East Jonathan S. Martel Suite 411 Jeremy C. Karpatkin Los Angeles, CA 90067 Bassel C. Korkor (310) 277-1482 Sara K. Pildis ARNOLD & PORTER LLP 555 Twelfth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20004 (202) 942-5000 Attorneys for Amici Curiae - i - TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ................................ 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................... 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 4 I. Americans Paid a Heavy Price For McCarthy Era Penalties on Speech and Association ............................................................ 4 II. The Supreme Court in the 1950s and 1960s Rejected McCarthy Era ‗Guilt by Association‘ Statutes as Impermissible ............... 9 A. AEDPA Penalizes the Relationship Between an Individual and a Designated Organization, in Violation of the Freedom of Association ................................................... 10 1. Congress Cannot Impose a ―Blanket Prohibition‖ on Association With Groups Having Legal and Illegal Aims .......................... 10 2. The Government Must Prove that Individuals Intend to Further the Illegal Aims of an Organization.......................................... 12 - ii - B. Like McCarthy Era Statutes, AEDPA Makes Constitutionally Protected Speech a Crime and is Unconstitutionally Vague, Chilling Free Speech .................................................. 14 1. AEDPA Unconstitutionally Penalizes Protected Speech in the Same Manner as McCarthy Era Laws .............................................. -

The Origins and Development of the Truman Doctrine

A Reluctant Call to Arms: The Origins and Development of the Truman Doctrine By: Samuel C. LaSala A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY University of Central Oklahoma Spring 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………i Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..ii Chapter One Historiography and Methodology…………..………………………..………1 Chapter Two From Allies to Adversaries: The Origins of the Cold War………………….22 Chapter Three A Failure to Communicate: Truman’s Public Statements and American Foreign Policy in 1946…….………………………………………………...59 Chapter Four Overstating His Case: Proclaiming the Truman Doctrine……………………86 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………120 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………………...127 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………….136 Acknowledgements No endeavor worth taking could be achieved without the support of one’s family, friends, and mentors. With this in mind, I want to thank the University of Central Oklahoma’s faculty for helping me become a better student. Their classes have deepened my fascination and love for history. I especially want to thank Dr. Xiaobing Li, Dr. Patricia Loughlin, and Dr. Jeffrey Plaks for their guidance, insights, and valuable feedback. Their participation on my thesis committee is greatly appreciated. I also want to thank my friends, who not only tolerated my many musings and rants, but also provided much needed morale boosts along the way. I want to express my gratitude to my family without whom none of this would be possible. To my Mom, Dad, and brother: thank you for sparking my love of history so very long ago. To my children: thank you for being patient with your Dad and just, in general, being awesome kids. -

Table of Contents Publisher’S Note

Table of Contents Publisher’s Note . ix Editor’s Introduction . xi Contributors . xiii VOLUME 1 Postwar Cold War Potsdam Agreement . 3 Stalin’s Election Speech, 1946 . 17 Churchill’s “ Iron Curtain” Speech . 25 Truman Doctrine Speech . 34 Speech on the Marshall Plan . 40 “The Sources of Soviet Content” . 45 Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (Rio Treaty) . 57 Vyshinky’s Speech to the UN General Assembly . 64 NATO Treaty . 68 Memorandum on Lifting the Soviet Blockade . 72 Dean Acheson on the “Loss” of China . 75 Atomic Explosion in the USSR . 79 International Control of Atomic Energy . 82 NSC 68: “United States Objectives and Programs for National Security” . 91 Report to the American People on Korea and US Policy in the Far East . 97 Statement by President Truman upon Signing the Mutual Security Act . .103 President Eisenhower—“The Chance for Peace” . .107 Mutual Defense Treaty between the United States and the Republic of Korea . .114 A “New Look” at National Defense Policy . .118 “Atoms for Peace” . .125 CIA Summary of the Overthrow of Premier Mossadeq of Iran . .132 Balkan Pact . .138 President Eisenhower to the President of the Council of Ministers of Vietnam . .143 Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty . .146 Baghdad Pact . .150 President Sukarno's Address at the Bandung Conference . .154 Warsaw Pact . .163 v Khrushchev on the “Cult of Personality” and Its Consequences . .167 Senator John F. Kennedy on America’s Stake in Vietnam . .176 Resolution of Hungarian Student Protestors . .182 Mao on the “Correct Handling of Contradictions among the People” . .186 Launching of the Sputnik Satellite . .195 Eisenhower on Science in National Security .