Recognizing Transnational Ties of Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Å Nyansere Norsk Modernisme

Å nyansere norsk modernisme Espen Johnsen Nordic Journal of Architectural Research Volym 19, Nr 1, 2006,8 pages Nordic Association for Architectural Research Espen Johnsen, Dept. of Philosophy, Classics, History of Art and Ideas University of Oslo Abstract: Keywords: Nuances in Norwegian Modernism Norwegian architecture, Scandinavian Doricism, Emotional Func- The article raises some issues and discuss problems when writ- tionalism , modernism, Arne Korsmo, Blakstad & Munthe-Kaas. ing about modern Norwegian architecture 1910–1940. Shall we for this period study parallel tendencies or focus strictly on tendencies toward an international Modernism? A paradox in the last 25 years Jeg vil innlede med å stille et spørsmål: Er det slik at vi i has been that while we in Scandinavia have tried to write the early Norden prøver å innskrive oss i modernismens arkitektur- history of Modernism, writers abroad have focused more on par- historie, mens verden for øvrig forsøker å skrive oss ut av allel tendencies including National Romanticism and Scandinavian den samme historien? Forestillingen om å kunne og ville Doricism. Functionalism in Scandinavia during the 1930s has been ”se modernismen i bakspeilet”, aksentuert av undertittelen seen as a stylistic dissipation in respond to the heroic modernis- ”dansk og norsk arkitektur og design i et historiografisk tic formcredo. Are villas and furniture by Norwegian architects like perspektiv” antyder at det er modernismens arkitektur og Magnus Poulsson, Blakstad & Munthe-Kaas, Knut Knutsen and Arne design som -

Rik På Historie - Et Riss Av Kulturhistoriens Fysiske Spor I Bærum

Rik på historie - et riss av kulturhistoriens fysiske spor i Bærum Regulering Natur og Idrett Forord Velkommen til en reise i Bærums rike kulturarv, - fra eldre Det er viktig at vi er bevisst våre kulturhistoriske, arki- steinalder, jernalder, middelalder og frem til i dag. Sporene tektoniske og miljømessige verdier, både av hensyn til vår etter det våre forfedre har skapt finner vi igjen over hele kulturarv og identitet, men også i en helhetlig miljø- og kommunen. Gjennom ”Rik på historie” samles sporene fra ressursforvaltning. vår arv mellom to permer - for å leses og læres. Heftet, som er rikt illustrert med bilder av kjente og mindre Sporene er ofte uerstattelige. Også de omgivelsene som kjente kulturminner og -miljøer, er full av historiske fakta kulturminnene er en del av kan være verdifulle. I Bærum og krydret med små anekdoter. Redaksjonsgruppen, som består kulturminner og kulturmiljøer av om lag 750 eien- består av Anne Sofie Bjørge, Tone Groseth, Ida Haukeland dommer, som helt eller delvis er regulert til bevaring, og av Janbu, Elin Horn, Gro Magnesen og Liv Frøysaa Moe har ca 390 fredete kulturminner. utarbeidet det spennende og innsiktsfulle heftet. I ”Rik på historie” legger forfatterne vekt på å gjenspeile Jeg håper at mange, både unge og eldre, lar seg inspirere til å kommunens særpreg og mangfold. Heftet viser oss hvordan bli med på denne reisen i Bærums rike historie. utviklingen har påvirket utformingen av bygninger og anlegg, og hvordan landskapet rundt oss er endret. Lisbeth Hammer Krog Det som gjør “Rik på historie” særlig interessant er at den er Ordfører i Bærum delt inn i både perioder og temaer. -

14 09 21 Nordics Gids 200Dpi BA ML

1 Impressies Oslo Vigelandpark Architecten aan het werk bij Snohetta Skyline in stadsdeel Bjørvika Stadhuis Oeragebouw (Snohetta) Noors architectuurcentrum Gyldendal Norsk Forlag (Sverre Fehn) Vliegveld Gardemoen (N.Torp) Mortensrud kirke (Jensen Skodvin) Ligging aan de Oslo Fjord Vikingschip Museum Nationaal museum 2 Impressies Stockholm Husbyparken Bonniers Konsthalle Royal Seaport Bibliotheek Strandparken Medelhavsmuseet HAmmersby sjostad Riksbanken Markus Kyrkan Arstabridge Terminal building Vasaparken 3 Inhoudsopgave Inhoudsopgave Programma 5 Contactgegevens 7 Deelnemerslijst 8 Plattegronden Oslo 9 Plattegronden Stockholm 11 Introductie Oslo 13 Noorse architectuur 15 Projecten Oslo 21 Introductie Stockholm 48 Projecten Stockholm 51 4 Programma Oslo OSLO, vrijdag 12 september 2014 6:55 KLM vlucht AMS-OSL 9:46 transfer met reguliere trein van vliegveld naar CS (nabij hotel) 10:10 bagage drop Clarion Royal Christiania Hotel, Biskop Gunnerus' gate 3, Oslo 10:35 reistijd metro T 1 Frognerseteren van Jernbanetorget T (Oslo S) naar halte Holmenkollen T 11:10 Holmenkollen ski jump, Kongeveien 5, 0787 Oslo 12:00 reistijd metro T 1 Helsfyr van Holmenkollen T naar halte Majoerstuen T 12:40 Vigelandpark, Nobels gate 32, Oslo 14:00 reistijd metro T 3 Mortensrud van Majorstuen T naar halte Mortensrud T 14:35 Mortensrud church, Mortensrud menighet, Helga Vaneks Vei 15, 1281 Oslo 15:20 reistijd metro 3 Sinsen van Mortensrud naar halte T Gronland 16:00 Norwegian Centre for Design and Architecture, DogA, Hausmanns gate 16, 0182 Oslo lopen naar hotel -

Reconstruction on Display: Arkitektenes Høstutstilling 1947–1949 As Site for Disciplinary Formation

Reconstruction on Display: Arkitektenes høstutstilling 1947–1949 as Site for Disciplinary Formation by Ingrid Dobloug Roede Master of Architecture The Oslo School of Architecture and Design, 2016 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2019 © 2019 Ingrid Dobloug Roede. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: Department of Architecture May 23, 2019 Certified by: Mark Jarzombek Professor of the History and Theory of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Nasser Rabbat Aga Khan Professor Chair of Department Committee for Graduate Students Committee Mark Jarzombek, PhD Professor of the History and Theory of Architecture Advisor Timothy Hyde, MArch, PhD Associate Professor of the History of Architecture Reader 2 Reconstruction on Display: Arkitektenes høstutstilling 1947-1949 As Site for Disciplinary Formation by Ingrid Dobloug Roede Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 23, 2019 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies Abstract With the liberation of Norway in 1945—after a war that left large parts of the country in ruins, had displaced tenfold thousands of people, and put a halt to civilian building projects—Norwegian architects faced an unparalleled demand for their services. As societal stabilization commenced, members of the Norwegian Association of Architects (NAL) were consumed by the following question: what would—and should—be the architect’s role in postwar society? To publicly articulate a satisfying answer, NAL organized a series of architectural exhibitions in the years 1947–1949. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 05 1 THIS IS ENTRA EIENDOM AS 3 COMMENTS OF THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 4 2004 HIGHLIGHTS 6 KEY FIGURES AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION 14 THE PROPERTY PORTFOLIO 17 ASSESSMENT OF MARKET VALUE – EVA 22 ANNUAL STATEMENT 32 ANNUAL ACCOUNTS 37 ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES 42 NOTES 55 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 66 OUR BUSINESS – STRATEGIC FOCUS 76 PROPERTY INDEX 81 CONTACTS In 2004, in collaboration with Tank Design, Entra Eiendom decided to publish a book about some of Entra’s finest properties in Norway. We sent Chris Harrison, one of Norway’s most exciting photographers, on a mission from Bodø in the north to Kristiansand in the south, in order to document the interiors and exteriors of our diverse property portfolio. He came back with a large number of photographs, which formed the basis for the book «M2 – ET STREIFTOG GJENNOM ENTRA EIENDOMS BYGNINGER». In November 2005 the 145-page book was ready, full of fantastic photographs and with texts written by Mona Jacobsen, Entra’s Director of Communications. Chris was born and bred in Jarrow, in the north-east of England, and in this annual report we have asked him to tells us a little bit about his encounter with our various buildings, which between them encompass a large part of Norway’s architectural history. You can see the results of this between chapters, where Chris has worked with Tank to create small, personal documents telling about his journey, about his meetings with some of our employees on site and not least about the trials and tribulations of being a photographer in the unpredict- able Norwegian weather. -

The Permanent Collection of 1925: Oslo Modernism in Paper and Models Mari Lending*

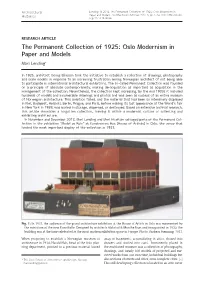

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Lending, M 2014 The Permanent Collection of 1925: Oslo Modernism in +LVWRULHV Paper and Models. Architectural Histories, 2(1): 3, pp. 1-14, DOI: http://dx.doi. org/10.5334/ah.be RESEARCH ARTICLE The Permanent Collection of 1925: Oslo Modernism in Paper and Models Mari Lending* In 1925, architect Georg Eliassen took the initiative to establish a collection of drawings, photography and scale models in response to an increasing frustration among Norwegian architect of not being able to participate in international architectural exhibitions. The so-called Permanent Collection was founded on a principle of absolute contemporaneity, making de-acquisition as important as acquisition in the management of the collection. Nevertheless, the collection kept increasing. By the mid 1930s it included hundreds of models and innumerable drawings and photos and was seen as nucleus of an entire museum of Norwegian architecture. This ambition failed, and the material that had been so intensively displayed in Kiel, Budapest, Helsinki, Berlin, Prague, and Paris, before making its last appearance at the World’s Fair in New York in 1939, was buried in storage, dispersed, or destroyed. Based on extensive archival research, this article chronicles a forgotten collection, framing it within a modernist culture of collecting and exhibiting architecture. In November and December 2013, Mari Lending and Mari Hvattum salvaged parts of the Permanent Col- lection in the exhibition “Model as Ruin” at Kunstnernes Hus (House of Artists) in Oslo, the venue that hosted the most important display of the collection in 1931. Fig. 1: In 1931, the audience of the grand architecture exhibition at the House of Artists in Oslo was mesmerized by the miniature of the new Kunsthalle. -

Future Nordic Concrete Architecture

Future Nordic Concrete Architecture Future Nordic Concrete Architecture Introduction Through the 20th century concrete has become the most used building material in the world. The usage of concrete has led to a new architecture which exploits the isotopic properties of concrete to generate new shapes. Despite the considerable amount of concrete used in architecture, the concrete is surprisingly little visible. Often concrete is only used as the material for the load‐bearing structures and afterwards hidden behind other facade‐materials. But concrete has a big unexploited potential in order to create beautiful shapes with spectacular textures on the surface. This potential has been explored through a number of buildings which can be characterized as concrete architecture. In this context concrete architecture is defined as: - Architecture where concrete is used as a dominating and visible material and/or - Architecture where concrete is expressed through the geometry. In the following, a number of projects characterized as Nordic concrete architecture is presented together with a description of the epochs of the history of concrete architecture to which they belong. Nordic Concrete Architecture In Scandinavia, conditions different from the most other places in the world prevail. The Nordic climate causes significant changing weather conditions during the 4 seasons. This results in significant fewer hours with sun. Add to this that the sun stands low in the sky – especially in the winter season. This condition has had great influence on the architecture combined with the cultural development in Scandinavia. The style of building has always been inspired of the neighbours in the south – but always with a local interpretation and the usage of local building materials. -

Generelt Innholdsfortegnelse 1 Rjukan

Områdevis beskrivelse Generelt Innholdsfortegnelse 1 Rjukan .............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Rjukan – bakgrunn, framvekst og særpreg ............................................................................. 2 1.2 Byformingsidealer omkring 1900 ............................................................................................ 3 1.2.1 Company towns og hagebybevegelsen ........................................................................... 3 1.2.2 «Egne-hjem» ................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Teoretisk byplanteori – noen begreper ................................................................................... 5 1.4 Arkitektur - Typiske stiltrekk fra perioden 1905 – 1920 .......................................................... 6 1.4.1 Nasjonal byggeskikk ........................................................................................................ 6 1.4.2 Jugendstilen ..................................................................................................................... 7 1.4.3 Nyklassisismen ................................................................................................................. 7 1.4.4 Sveitserstil: 1840 - 1920 .................................................................................................. 8 1.5 Landskaps- og naturmessige forutsetninger på Rjukan: -

New Viking Age Museum at Bygdøy

NEW VIKING AGE MUSEUM AT BYGDØY Audun Wold Andresen & Simon Rhode Malm ma4-ark46 - June 2015 1 2 “The taste of the apple […] lies in the contact of the fruit with the palate, not in the fruit itself; in a similar way […] poetry lies in the meeting of poem and reader, not in the lines of symbols printed on the pages of a book”. (Juhani Pallasmaa, 1998, p. 17) If the same is true for architecture, the beauty must lie in the bodily encoun- ter; in the awakening of the human senses. Necessarily, architectural expe- rience is grounded in the dialogue and interaction with the environment, to a degree in which a separation of the image of self and its spatial existence is impossible. According to Pallasmaa (2012) we measure the world through our bodily existence, consequently making our experiential world centered round the perception of the human body. This is an interest of ours; the impact of architecture on our perception, on the human experience of space. And thus, this is from where the master thesis departs. Audun Andresen & Simon Malm Stud. MS.c Eng. Arch 3 4 PREFACE THE NEW VIKING AGE MUSEUM ‘New Viking Age Museum at Bygdøy’ is developed by Audun Wold Andresen and Simon Rhode Malm on the 4th and final semester of the Architectural M.Sc. program at the Department of Architecture, Design and Media Technology at the University of Aalborg, Denmark. This Master Thesis deals with the design and organization of an extension to an existing museum, located at a small peninsula near Oslo, Norway. -

Medlemsblad for Lillehammer Museums Venner

NR. 1 FEBRUAR 2020, 28. ÅRGANG Medlemsblad for Lillehammer Museums Venner MEDLEMSKAP LMV 2020 INNHOLD DSSVs ekstraordinære årsmøte 26. september Leder side 3 2019 besluttet å endre venneforeningens virkeområde fra bare Maihaugen til å omfatte Kjære lesere side 4 alle de 6 museene som inngår i Stiftelsen Den første direktør side 5 Lillehammer Museum: Stortorgets perle side 7 Maihaugen Lillehammer kunstmuseum Nye styremedlemmer i SLM side 10 Bjerkebæk Aulestad Duken på Aulestad side 11 Norges Olympiske Museum Arts and crafts på Lillehammer side 14 Norges Postmuseum, «MAIHAUGEN-METODEN» side 16 Navnet på venneforeningen er Lillehammer Museums Venner (LMV). «Det er fornyes man skal» side 18 Som medlem her får du fri adgang til alle Digitalt museum side 20 disse museene i hele kalenderåret (inklusiv Spesialomvisninger / Vennetur side 22 Barnas Sommer- og Vinterdag, Julemarkedet, osv). I tillegg får du direkte invitasjon til spesial- Ressurspersonene side 23 arrangementer på alle museene (når du har betalt kontingent og registrert din e-postadresse). Program for museene side 24 Venneforeningsbladet får du i posten ! tre ganger i året. Velkommen I tillegg gir medlemskapet fri adgang til en rekke andre friluftsmuseer i Norden (Norsk til årsmøte Folkemuseum, Sverresborg etc). som du finner på lillehammermuseum.no/lmv Tirsdag 24. mars 2020 kl. 18.30 i Auditoriet på Maihaugen MEDLEMSKONTINGENT: Enkeltmedlemskap med årskort kr 700/ DAGSORDEN kalenderår • Årsmelding og regnskap for 2019 Familiemedlemskap med årskort kr 1 050/ • Innkomne forslag kalenderår • Valg på styreleder, styremedlemmer, Familiemedlemskap gjelder et varamedlemmer, valgkomite og revisor par og alle egne barn/barnebarn under 16 år. • Direktør Jostein Skurdal orienterer om status og planer for SLM • Servering i kafeteriaen etter møtet Lillehammer Museums Venner Årsmelding og regnskap finner du på vår hjemmeside Maihaugvn 1, 2609 Lillehammer http://lillehammermuseum.no/lmv/aarsmote Bankgiro 2000.05.17608 eller dokumentene kan hentes i butikken Informasjon 6128 8900 på Maihaugen. -

Oslo Åpne Hus 2006 Besøk Arkitektoniske Perler Og Hemmelige Hager 14

Riv ut ... Velkommen til OSLO ÅPNE HUS 2006 BESØK ARKITEKTONISKE PERLER OG HEMMELIGE HAGER 14. – 15. OKTOBER 2006 Buegangen Elsero. Foto: Signe Dons/Scanpix OSLO ÅPNE HUS er et spesielt arrangement som skal gi byens befolkning anledning til å besøke et stort utvalg av arkitektonisk og kultur- historisk betydningsfulle bygninger og anlegg i Oslo som vanligvis ikke er åpne for publikum. Mange vakre hager og parker kan også besøkes og beundres. Hensikten er at så mange som mulig skal kunne glede seg over de enestående bygninger og hageanlegg vi har i Oslo og omegn. Lørdag 14. og søndag 15. oktober åpnes dørene inn til deres spennende indre liv: offentlige bygninger, kirker, næringsbygg, hager og parker, arkitektkontor, undervisningsbygg, rettsbygninger og enkelte private boliger – stort og lite, enkelt og overdådig. Adgang til alle bygninger og hageanlegg er gratis. Enkelte steder vil adgangen kunne være begrenset til spesielle rom eller deler av anlegg, og i tillegg vil adgang kunne være begrenset til egne omvisninger og antall besøkende. Se nærmere under åpningstid/omvisning. Ved stor pågang må påregnes ventetid og adgang i puljer. ARRANGØRER: NORSKE ARKITEKTERS LANDSFORBUND * NORSKE INTERIØRARKITEKTERS OG MØBELDESIGNERES LANDSFORENING * NORSKE LANDSKAPSARKITEKTERS FORENING Det gjøres oppmerksom på at hver bygnings eier(e) står ansvarlig for åpningstider, omvisninger og sikkerhetstiltak. NIL Skulle man nektes adgang til noen av bygningene står dette for eiers egen regning. Arrangørene av OSLO ÅPNE HUS tar intet ansvar for endringer i de opplysninger som her er oppgitt. Eventuelle spørsmål kan rettes via e-post til Norske Arkitekters Landsforbund (NAL) [email protected], NLA Josefinesgt. 34, 0315 Oslo, tlf. -

Historical Museum Was Designed by the Norwegian Architect Henrik Bull

Photo: KMH, UiO Photo: Photo: Nina Wallin Hansen, KMH,UiO Wallin Nina Photo: Historical Museum was designed by the Norwegian architect The Viking Ship Museum is one of the signature works by the Henrik Bull, and is one of the most impressive Art Noveau Norwegian architect Arnstein Arneberg. The hall housing the buildings in Norway. The Museum exhibits Ethnographic, Oseberg ship was completed in 1926, and the halls for the ships Numismatic and Archaeological collections. The Medieval from Gokstad and Tune were opened in 1932. After much delay, Gallery displays a unique and rich collection of stave church the last hall was completed in 1957. This hall houses a selection portals from 12th and 13th centuries. of the other finds from the ship burials Akershus Castle (left) dates back to the late 1290s. After a fire in 1624, the medieval town, Gamlebyen, was replaced by the new city, Christiania, named after king Christian IV, situated close to Akershus Fortress. Today the city of Oslo embraces several historical buildings from mid-17th Nina Aldin Photo: century in Kvadraturen, and the late 17th century’s Oslo Cathedral (right) by the market square, Stortorvet. The Royal Palace, University of Oslo Aula and Stortinget are located along the main street Karl Johans gate. Photo: Forsvarets mediesenter Forsvarets Photo: Photo: Erik Berg Photo: Photo: Bjørn Erik Pedersen Photo: University of Oslo (city centre campus) was designed for the first Oslo Opera House, from 2008, was designed by the architect university campus in Norway. It was created by Christian Heinrich firm Snøhetta. The roof is a platform accessible to all creating Grosch and approved by K.