Future Nordic Concrete Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring the Static and Dynamic Behavior of the New Svinesund Bridge

Monitoring the static and dynamic behavior of The New Svinesund Bridge R. Karoumi1 and P. Harryson2 1 The Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Stockholm, Sweden 2 The Swedish Transport Administration, Sweden ABSTRACT: The New Svinesund Bridge across the Ide Fjord between Norway and Sweden is a structurally complicated bridge. Due to the uniqueness of the design and the importance of the bridge, an extensive monitoring prog ram was i nitiated. The ins talled monitoring system continuously logs data (accelerations, displacements, strains, hanger forces, temperatures, wind speed and wind directio n) from 7 2 sensors and has gathered data since the casting of the first arch segment in the spring of 2003. As part of the monitoring programme, comprehensive static and dynamic load tests hav e al so been undertaken ju st b efore bridge opening. Thi s paper describes t he i nstrumentation used fo r monitoring the stru ctural behavior of the bri dge a nd presents inte resting r esults such a s measured str ains, di splacements and dynamic pr operties. Results are compared with theoretic values based on the FE-model of the bridge. 1 INTRODUCTION The New Svinesund Bridge is structurally complicated. The design of the bridge is a result of an international design contest. The bridge forms a part of the European highway, E6, which is the main route for all road traffic between the cities Gothenburg in Sweden and Oslo in Norway. Due to the uniqueness of design and the importance of the bri dge, an ex tensive monitoring program was in itiated. -

Funkisperlen Har Gjenoppstått I Ekebergåsen Innhold

EIENDOMSSPAR årsrapport / 2004 Funkisperlen har gjenoppstått i Ekebergåsen Innhold 01 adm. dir. 02 2004 - i korte trekk 03 hovedtall 04 styret 05 årsberetning 10 resultatregnskap 11 balanse 12 kontantstrømoppstilling 13 noter 21 revisjonsberetning 22 aksjonærforhold/ corporate governance 24 verdijustert balanse pr. 31.12 04 25 sensitivitetsanalyse 26 verdiutvikling 2004 27 verdsettelsesprinsipper 27 leiekontraktsstruktur 28 donasjoner og offentlige utsmykninger 30 eiendommer 37 hoteller og restauranter 38 Pandox 42 prosjekter 44 Ekebergrestauranten 64 markedsanalyse 73 administrasjonen 74 english summary 76 financial information design / designmal: Dugg Design produksjon: Rita Husebæk, Eiendomsspar tekst temadel: Hilde Bringsli trykk: Mentor Media foto: Ole Walter Jacobsen Nicolas Tourrenc, forsidefoto Anna Littorin Oslo Bymuseum: Wilse Scanpix: Morten Holm adm. dir. gode tider Det sies at det i eiendom er bedre å være Pandox, som eier 45 hoteller med totalt idiot i et godt marked enn geni i et dårlig. 8.900 rom i Nord-Europa, ble foretatt på Det er tilbud og efterspørselsbalansen i et gunstig tidspunkt. utleiemarkedet og renten som er de to I Eiendomsspar ser vi for øyeblikket viktigste verdidriverne i eiendomsmarke- lyst på fremtiden. Eiendomsmarkedet er det. Disse to faktorer kan den enkelte fremdeles i bedring, vår eiendomsmasse eiendomsbesitter ikke påvirke i nevnever- er av høy kvalitet og vi vet at de regn- dig grad, så aktørene er på mange måter skapsmessige resultater for Eiendomsspar prisgitt den generelle markedsutviklingen. i 2005 vil bli betydelig bedre enn i 2004. Vi I 2004 bedret eiendomsmarkedet seg kan ikke legge skjul på at vi efter noen betydelig, først og fremst gjennom verdi- markedsmessig utfordrende år, nå gleder økninger. -

Ciudad Y Territorio Virtual

A NEW LANGUAGE IS BORN PATRICK MCGLOIN Director General ViaNova IT AS Sandvika - Noruega www.vianovasystems.com All professions have developed their own language. A professional language is mainly used to ensure clear communication within the profession but also has been used to mystify and ensure status. Doctors, lawyers, scientist and yes Civil Engineers have developed a communication that is specific to their particular area. This worked well as long as the necessity to communicate was limited to the profession or the chosen few that needed to interact. Today this is no longer good enough. Our society has become more and more complex and the requirements to a design process have increased enormously. Many people and groups inside and outside the design teams have a right and need to understand what is happing and what the result will be. This applies to both large and small engineering projects. Without a language that is easily understood the risk increases that “bad” decisions are made, and also opens for design mistakes. A middle size-engineering project be it a new road, a new rail line or an urban renewal project is a long process including the assessment of many alternatives. It can also include environmental impact studies and changes or improvements to utilities. It always enjoys a high media profile both positive and negative but often negative with interest groups all trying to influence the result. The role of the design group is to present the various alternatives in a professional way giving the decision makers the best possible basis to chose the best solution. -

Kingdom of Sweden

Johan Maltesson A Visitor´s Factbook on the KINGDOM OF SWEDEN © Johan Maltesson Johan Maltesson A Visitor’s Factbook to the Kingdom of Sweden Helsingborg, Sweden 2017 Preface This little publication is a condensed facts guide to Sweden, foremost intended for visitors to Sweden, as well as for persons who are merely interested in learning more about this fascinating, multifacetted and sadly all too unknown country. This book’s main focus is thus on things that might interest a visitor. Included are: Basic facts about Sweden Society and politics Culture, sports and religion Languages Science and education Media Transportation Nature and geography, including an extensive taxonomic list of Swedish terrestrial vertebrate animals An overview of Sweden’s history Lists of Swedish monarchs, prime ministers and persons of interest The most common Swedish given names and surnames A small dictionary of common words and phrases, including a small pronounciation guide Brief individual overviews of all of the 21 administrative counties of Sweden … and more... Wishing You a pleasant journey! Some notes... National and county population numbers are as of December 31 2016. Political parties and government are as of April 2017. New elections are to be held in September 2018. City population number are as of December 31 2015, and denotes contiguous urban areas – without regard to administra- tive division. Sports teams listed are those participating in the highest league of their respective sport – for soccer as of the 2017 season and for ice hockey and handball as of the 2016-2017 season. The ”most common names” listed are as of December 31 2016. -

14 09 21 Nordics Gids 200Dpi BA ML

1 Impressies Oslo Vigelandpark Architecten aan het werk bij Snohetta Skyline in stadsdeel Bjørvika Stadhuis Oeragebouw (Snohetta) Noors architectuurcentrum Gyldendal Norsk Forlag (Sverre Fehn) Vliegveld Gardemoen (N.Torp) Mortensrud kirke (Jensen Skodvin) Ligging aan de Oslo Fjord Vikingschip Museum Nationaal museum 2 Impressies Stockholm Husbyparken Bonniers Konsthalle Royal Seaport Bibliotheek Strandparken Medelhavsmuseet HAmmersby sjostad Riksbanken Markus Kyrkan Arstabridge Terminal building Vasaparken 3 Inhoudsopgave Inhoudsopgave Programma 5 Contactgegevens 7 Deelnemerslijst 8 Plattegronden Oslo 9 Plattegronden Stockholm 11 Introductie Oslo 13 Noorse architectuur 15 Projecten Oslo 21 Introductie Stockholm 48 Projecten Stockholm 51 4 Programma Oslo OSLO, vrijdag 12 september 2014 6:55 KLM vlucht AMS-OSL 9:46 transfer met reguliere trein van vliegveld naar CS (nabij hotel) 10:10 bagage drop Clarion Royal Christiania Hotel, Biskop Gunnerus' gate 3, Oslo 10:35 reistijd metro T 1 Frognerseteren van Jernbanetorget T (Oslo S) naar halte Holmenkollen T 11:10 Holmenkollen ski jump, Kongeveien 5, 0787 Oslo 12:00 reistijd metro T 1 Helsfyr van Holmenkollen T naar halte Majoerstuen T 12:40 Vigelandpark, Nobels gate 32, Oslo 14:00 reistijd metro T 3 Mortensrud van Majorstuen T naar halte Mortensrud T 14:35 Mortensrud church, Mortensrud menighet, Helga Vaneks Vei 15, 1281 Oslo 15:20 reistijd metro 3 Sinsen van Mortensrud naar halte T Gronland 16:00 Norwegian Centre for Design and Architecture, DogA, Hausmanns gate 16, 0182 Oslo lopen naar hotel -

Modelling of the Response of the New Svinesund Bridge FE Analysis of the Arch Launching

Modelling of the response of the New Svinesund Bridge FE Analysis of the arch launching Master’s Thesis in the International Master’s Programme Structural Engineering SENAD CANOVIC AND JOAKIM GONCALVES Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Division of Structural Engineering Concrete Structures CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Göteborg, Sweden 2005 Master’s Thesis 2005:39 MASTER’S THESIS 2005:39 Modelling of the response of the New Svinesund Bridge FE Analysis of the arch launching Master’s Thesis in the International Master’s Programme Structural Engineering SENAD CANOVIC AND JOAKIM GONCALVES Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Division of Structural Engineering Concrete Structures CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Göteborg, Sweden 2005 Modelling the response of the New Svinesund Bridge FE Analysis of the arch launching Master’s Thesis in the International Master’s Programme Structural Engineering SENAD CANOVIC AND JOAKIM GONCALVES © SENAD CANOVIC, JOAKIM GONCALVES, Göteborg, Sweden 2005 Master’s Thesis 2005:39 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Division of Structural Engineering Concrete Structures Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Göteborg Sweden Telephone: + 46 (0)31-772 1000 Cover: FE model of the New Svinesund Bridge and two pictures taken during the construction of the bridge. Chalmers reproservice Göteborg, Sweden 2005 Modelling the response of the New Svinesund Bridge FE Analysis of the arch launching Master’s Thesis in the International Master’s Programme Structural Engineering SENAD CANOVIC AND JOAKIM GONCALVES Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Division of Structural Engineering Concrete Structures Chalmers University of Technology ABSTRACT There is a necessity to improve the methods for bridge assessment because they are over-conservative. -

EIENDOMSSPAR ÅRSRAPPORT Eiendomsspar Årsrapport 2013

2013 EIENDOMSSPAR ÅRSRAPPORT Eiendomsspar årsrapport 2013 3 _ Adm. direktør 4 _ Nøkkeltall 5 _ Organisasjonen/Ansatte 6 _ Eiendomsspars historie 8 _ Visjon og viktigste målsettinger 8 _ Etikk og samfunnsansvar 9 _ Strategi 10 _ Energi- og miljøstrategi 12 _ Virksomhetsområder og segmenter 13 _ 2013 i korte trekk 14 _ Styret 15 _ Styrets årsberetning 22 _ Resultatregnskap 23 _ Balanse 24 _ Kontantstrømoppstilling 25 _ Noter 32 _ Revisjonsberetning 34 _ Eierstyring og selskapsledelse 37 _ Aksjonæroversikt 38 _ Verdivurdering pr 31.12.13 39 _ Verdiutvikling 2013 40 _ Verdijustert balanse pr 31.12.13 41 _ Donasjoner og offentlige utsmykninger 47 _ Eiendommer 51 _ Leiekontraktsstruktur 56 _ Pandox/Norgani Hotels 59 _ Prosjekter 66 _ Vi former våre bygninger, deretter former de oss 102 _ Markedsanalyse 110 _ English summary 112 _ Financial information 2 EIENDOMSSPAR ÅRSRAPPORT ADM DIREKTØR Christian Ringnes Adm. direktør Adm. dir Syklisk medvind Etter regn kommer sol. Finanskrise og gjeldsboble i Kina, oljeprisutviklingen og kredittkrise er i ferd med å bli erstattet av høyt norsk kostnadsnivå, har alle kimen bedret kreditt-tilgjengelighet og i seg til å kunne få dagens sykliske med- internasjonale vekstimpulser. Og siden vind til å endres til utfordrende motvind renten fremdeles er på rekordlave nivåer på noen års sikt. og nybyggingen enn så lenge er edruelig, ser utsiktene i næringseiendoms- Eiendomsspar velger i disse omgivelser markedet ganske gode ut. å fortsette sin sten på sten ekspansjon – uten større kvantesprang. Markedet Eiendomsspar har da også hatt et er ikke billig og selv om det er fristende tilfredsstillende 2013. -

En Reise I Norsk TREARKITEKTUR

En reise i Norsk TREARKITEKTUR |1 Velkommen til en reise i norsk trearkitektur Dette heftet viser vei til 21 norske bygninger som i det alt vesentlige er bygd og oppført i naturens eget fornybare materiale – trevirke. Noen er riktig gamle og viser hvilke sterke tradisjoner vi helt siden middelalderen, har hatt for å bygge og bo i trehus. Andre er nye og moderne og viser hvilke muligheter tre har til også å være framtidens byggemateriale. Tre er et miljøvennlig bygningsmateriale. Det er vårt eneste fornybare råstoff til bygningsformål og det krever lite energi ved framstilling. Produkter av trevirke lagrer karbon gjennom hele sin levetid og det kan brukes som miljøvennlig energi når byggets levetid er over. I Norge er det også slik at vi i dag høster bare ca 1/3 av den årlige tilveksten av tømmer i skogen. Råstoff har vi mer enn Trygve Slagsvold Vedum nok av. Landbruks- og matminister Økt bruk av tre i samfunnet er på denne bakgrunn viktig for den norske regjeringen. Gjennom ulike virkemidler legges det til rette for økt trebruk for å oppnå mer varig binding av karbon og andre miljøgevinster. Arkitektene er vesentlige premissgivere for hva som bygges, og hvordan våre nye bygg blir utformet. Mange norske arkitektfirmaer har de siste årene i økende grad tatt tre i bruk i sine nye prosjekter – og mange har vunnet internasjonale priser. Flere av disse prosjektene blir presentert i dette heftet. Med mot, djervhet og kreativitet er det blitt oppført bygg som blir en opple- velse i seg selv – og en attraktivitet også for reiselivet. -

Approach to Cef for the Oslo-Göteborg Railway Stretch

APPROACH TO CEF FOR THE OSLO-GÖTEBORG RAILWAY STRETCH STRING NETWORK FINAL REPORT 1.09.2020 Ramboll - Approach to CEF for the Oslo-Göteborg railway stretch Project name Approach to CEF f or the Oslo-Göteborg railway stretch Ramboll C lient name STRING NETWORK Lokgatan 8 211 20 Malmö Type of proposal FINAL REPORT Date 1 September 2020 T +4 6 (0 )1 0 615 60 0 0 Bidder/Tender Ramboll Sweden AB https://se.ramboll.com Ramboll Sverige AB Org. nummer 556133-0506 Ramboll - Approach to CEF for the Oslo-Göteborg railway stretch CONTENTS 1. THE CONTEXT 2 1.1 STRING vision and strategic priorities 2 1.2 The weak link of the Oslo-Göteborg railway connection in the corridor perspective 3 1.3 Purpose of the report 4 2. TRANSPORT SYSTEM SETTING FOR THE INVESTMENT 6 2.1 The railway system in cross-border area between Oslo and Göteborg Fejl! Bogmærke er ikke defineret. 2.2 Status of railway infrastructure in the Oslo-Göteborg stretch 6 2.3 The Oslo – Göteborg railway stretch in national transport plans 7 2.4 National planning framework for the remaining bottleneck 9 2.5 Preparations for the new national transport plan in Sweden 11 3. EUROPEAN PLANNING PRE-REQUISITES AND FUNDING OPTIONS FOR THE PROJECT 13 3.1 The European transport policy reference for investment 13 3.1.1 The European Green Deal as the EU Commission priority for 2019-2024 13 3.1.2 TEN-T Policy and its future evolution 14 3.2 European funding options for the double track construction project 16 3.2.1 European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) 16 3.2.2 Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) 17 3.2.3 Financial instruments for sustainable infrastructure under the InvestEU programme 18 3.2.4 Other support instruments for transport by the European Investment Bank (EIB) 22 3.3 CEF framework conditions for the double track railway investment 22 3.3.1 Compliance with objectives and priorities 23 3.3.2 Eligibility of actions and countries 23 3.3.3 Budget and co-funding rates 24 3.3.4 Types of CEF calls and call requirements 25 3.3.5 Award criteria 29 4. -

Fortellinger Om Norsk Brutalisme

Lars Erik Brustad Melhus FORTELLINGER OM NORSK BRUTALISME En studie av et arkitekturbegreps historie Masteroppgave i Arkitektur, Trondheim våren 2013 Lars Erik Brustad Melhus Fortellinger om norsk brutalisme En studie av et arkitekturbegreps historie Masteroppgave i arkitektur Institutt for byggekunst, historie og teknologi Fakultet for arkitektur og billedkunst NTNU Trondheim våren 2013 Forord Da jeg søkte på arkitektstudiet ved NTNU for seks år siden var jeg drevet av en lyst til å utforske sammenhengene mellom teknologi, samfunn og estetiske valg. Arkitekturfaget stiller spørsmål ved alle disse momentene, og jeg håpet å tre inn i et bredt fagområde. Lite visste jeg dengang om at jeg skulle avslutte studietiden min med en masteroppgave i arkitekturhistorie. Jeg er glad arkitekturfaget også gir plass til idéhistoriske studier, og jeg har funnet stor glede i å fordype meg i de teoretiske sidene ved disiplinen. Takket være en rekke personer, har jeg gjennomlevd en svært lærerik og spennende prosess. Først og fremst vil jeg få rette en stor takk til min hovedveileder Dag Nilsen for gode og konstruktive samtaler, samt hjelp til å navigere kursen underveis. Jeg vil også takke min biveileder Martin Braathen, for å hjelpe meg igang og hele tiden kreve konsise IRUPXOHULQJHU9LGHUHPnMHJInWDNNH0DUN0DQV¿HOGYHG$+2VRPRSSPXQWUHW meg til å forfølge min interesse for arkitekturhistorie, og som hele tiden har vært en ”enthusiastic cheerleader”. Eivind Kasa som viste meg at arkitekturfeltet ikke bare består i prosjektering, men også kan være en idéhistorisk disiplin. Ingrid, Rikke og Frida for å ha bidratt til å fylle dette semesteret med trivsel og engasjerte diskusjoner. Familie og venner som har holdt ut med uttallige forklaringer på en, tross alt, snever problemstilling. -

The Permanent Collection of 1925: Oslo Modernism in Paper and Models Mari Lending*

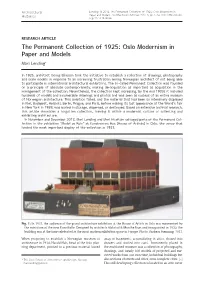

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Lending, M 2014 The Permanent Collection of 1925: Oslo Modernism in +LVWRULHV Paper and Models. Architectural Histories, 2(1): 3, pp. 1-14, DOI: http://dx.doi. org/10.5334/ah.be RESEARCH ARTICLE The Permanent Collection of 1925: Oslo Modernism in Paper and Models Mari Lending* In 1925, architect Georg Eliassen took the initiative to establish a collection of drawings, photography and scale models in response to an increasing frustration among Norwegian architect of not being able to participate in international architectural exhibitions. The so-called Permanent Collection was founded on a principle of absolute contemporaneity, making de-acquisition as important as acquisition in the management of the collection. Nevertheless, the collection kept increasing. By the mid 1930s it included hundreds of models and innumerable drawings and photos and was seen as nucleus of an entire museum of Norwegian architecture. This ambition failed, and the material that had been so intensively displayed in Kiel, Budapest, Helsinki, Berlin, Prague, and Paris, before making its last appearance at the World’s Fair in New York in 1939, was buried in storage, dispersed, or destroyed. Based on extensive archival research, this article chronicles a forgotten collection, framing it within a modernist culture of collecting and exhibiting architecture. In November and December 2013, Mari Lending and Mari Hvattum salvaged parts of the Permanent Col- lection in the exhibition “Model as Ruin” at Kunstnernes Hus (House of Artists) in Oslo, the venue that hosted the most important display of the collection in 1931. Fig. 1: In 1931, the audience of the grand architecture exhibition at the House of Artists in Oslo was mesmerized by the miniature of the new Kunsthalle. -

Generelt Innholdsfortegnelse 1 Rjukan

Områdevis beskrivelse Generelt Innholdsfortegnelse 1 Rjukan .............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Rjukan – bakgrunn, framvekst og særpreg ............................................................................. 2 1.2 Byformingsidealer omkring 1900 ............................................................................................ 3 1.2.1 Company towns og hagebybevegelsen ........................................................................... 3 1.2.2 «Egne-hjem» ................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Teoretisk byplanteori – noen begreper ................................................................................... 5 1.4 Arkitektur - Typiske stiltrekk fra perioden 1905 – 1920 .......................................................... 6 1.4.1 Nasjonal byggeskikk ........................................................................................................ 6 1.4.2 Jugendstilen ..................................................................................................................... 7 1.4.3 Nyklassisismen ................................................................................................................. 7 1.4.4 Sveitserstil: 1840 - 1920 .................................................................................................. 8 1.5 Landskaps- og naturmessige forutsetninger på Rjukan: