D:\AKAR\Problemating Language S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EIA & EC for Kathalchari Field Development, Block

EIA & EC for Kathalchari Field Development, Block (AA-ONN-2002/1), Tripura Final EIA Report Prepared for: Jubilant Oil and Gas Private Limited Prepared by: SENES Consultants India Pvt. Ltd. June, 2016 EIA for development activities of hydrocarbon, installation of GGS & pipeline laying at Kathalchari FINAL REPORT EIA & EC for Kathalchari Field Development, Block (AA-ONN-2002/1), Tripura M/s Jubilant Oil and Gas Private Limited For on and behalf of SENES Consultants India Ltd Approved by Mr. Mangesh Dakhore Position held NABET-QCI Accredited EIA Coordinator for Offshore & Onshore Oil and Gas Development and Production Date 28.12.2015 Approved by Mr. Sunil Gupta Position held NABET-QCI Accredited EIA Coordinator for Offshore & Onshore Oil and Gas Development and Production Date February 2016 The EIA report preparation have been undertaken in compliance with the ToR issued by MoEF vide letter no. J-11011/248/2013-IA II (I) dated 28th January, 2014. Information and content provided in the report is factually correct for the purpose and objective for such study undertaken. SENES/M-ESM-20241/June, 2016 i JOGPL EIA for development activities of hydrocarbon, installation of GGS & pipeline laying at Kathalchari INFORMATION ABOUT EIA CONSULTANTS Brief Company Profile This Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report has been prepared by SENES Consultants India Pvt. Ltd. SENES India, registered with the Companies Act of 1956 (Ranked No. 1 in 1956), has been operating in the county for more than 11 years and holds expertise in conducting Environmental Impact Assessments, Social Impact Assessments, Environment Health and Safety Compliance Audits, Designing and Planning of Solid Waste Management Facilities and Carbon Advisory Services. -

7=SINO-INDIAN Phylosector

7= SINO-INDIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 525 7=SINO-INDIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector comprises 22 sets of languages spoken by communities in eastern Asia, from the Himalayas to Manchuria (Heilongjiang), constituting the Sino-Tibetan (or Sino-Indian) continental affinity. See note on nomenclature below. 70= TIBETIC phylozone 71= HIMALAYIC phylozone 72= GARIC phylozone 73= KUKIC phylozone 74= MIRIC phylozone 75= KACHINIC phylozone 76= RUNGIC phylozone 77= IRRAWADDIC phylozone 78= KARENIC phylozone 79= SINITIC phylozone This continental affinity is composed of two major parts: the disparate Tibeto-Burman affinity (zones 70= to 77=), spoken by relatively small communities (with the exception of 77=) in the Himalayas and adjacent regions; and the closely related Chinese languages of the Sinitic set and net (zone 79=), spoken in eastern Asia. The Karen languages of zone 78=, formerly considered part of the Tibeto-Burman grouping, are probably best regarded as a third component of Sino-Tibetan affinity. Zone 79=Sinitic includes the outer-language with the largest number of primary voices in the world, representing the most populous network of contiguous speech-communities at the end of the 20th century ("Mainstream Chinese" or so- called 'Mandarin', standardised under the name of Putonghua). This phylosector is named 7=Sino-Indian (rather than Sino-Tibetan) to maintain the broad geographic nomenclature of all ten sectors of the linguasphere, composed of the names of continental or sub-continental entities. -

Committee on the Welfare of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (2010-2011)

SCTC No. 737 COMMITTEE ON THE WELFARE OF SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES (2010-2011) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) TWELFTH REPORT ON MINISTRY OF TRIBAL AFFAIRS Examination of Programmes for the Development of Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PTGs) Presented to Speaker, Lok Sabha on 30.04.2011 Presented to Lok Sabha on 06.09.2011 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 06.09.2011 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI April, 2011/, Vaisakha, 1933 (Saka) Price : ` 165.00 CONTENTS PAGE COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE ................................................................. (iii) INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ (v) Chapter I A Introductory ............................................................................ 1 B Objective ................................................................................. 5 C Activities undertaken by States for development of PTGs ..... 5 Chapter II—Implementation of Schemes for Development of PTGs A Programmes/Schemes for PTGs .............................................. 16 B Funding Pattern and CCD Plans.............................................. 20 C Amount Released to State Governments and NGOs ............... 21 D Details of Beneficiaries ............................................................ 26 Chapter III—Monitoring of Scheme A Administrative Structure ......................................................... 36 B Monitoring System ................................................................. 38 C Evaluation Study of PTG -

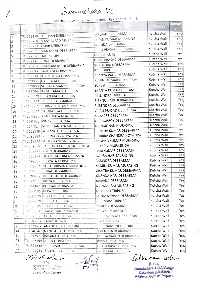

List of School Under South Tripura District

List of School under South Tripura District Sl No Block Name School Name School Management 1 BAGAFA WEST BAGAFA J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 2 BAGAFA NAGDA PARA S.B State Govt. Managed 3 BAGAFA WEST BAGAFA H.S SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 4 BAGAFA UTTAR KANCHANNAGAR S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 5 BAGAFA SANTI COL. S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 6 BAGAFA BAGAFA ASRAM H.S SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 7 BAGAFA KALACHARA HIGH SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 8 BAGAFA PADMA MOHAN R.P. S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 9 BAGAFA KHEMANANDATILLA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 10 BAGAFA KALA LOWGONG J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 11 BAGAFA ISLAMIA QURANIA MADRASSA SPQEM MADRASSA 12 BAGAFA ASRAM COL. J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 13 BAGAFA RADHA KISHORE GANJ S.B. State Govt. Managed 14 BAGAFA KAMANI DAS PARA J.B. SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 15 BAGAFA ASWINI TRIPURA PARA J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 16 BAGAFA PURNAJOY R.P. J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 17 BAGAFA GARDHANG S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 18 BAGAFA PRATI PRASAD R.P. J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 19 BAGAFA PASCHIM KATHALIACHARA J.B. State Govt. Managed 20 BAGAFA RAJ PRASAD CHOW. MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 21 BAGAFA ALLOYCHARRA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 22 BAGAFA GANGARAI PARA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 23 BAGAFA KIRI CHANDRA PARA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 24 BAGAFA TAUCHRAICHA CHOW PARA J.B TTAADC Managed 25 BAGAFA TWIKORMO HS SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 26 BAGAFA GANGARAI S.B SCHOOL State Govt. -

Bru-Reang-Final Report 23:5

Devising Pathways for Appropriate Repatriation of Children of Bru-Reang Community Ms. Stuti Kacker (IAS) Chairperson National Commission for Protection of Child Rights The National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) emphasizes the principle of universality and inviolability of child rights and recognises the tone of urgency in all the child related policies of the country. It believes that it is only in building a larger atmosphere in favour of protection of children’s rights, that children who are targeted become visible and gain confidence to access their entitlements. Displaced from their native state of Mizoram, Bru community has been staying in the make-shift camps located in North Tripura district since 1997 and they have faced immense hardship over these past two decades. Hence, it becomes imperative for the National Commission of Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) to ensure that the legal and constitutional rights of children of this community are protected. For the same purpose, NCPCR collaborated with QCI to conduct a study to understand the living conditions in the camps of these children and devise a pathway for the repatriation and rehabilitation of Bru-Reang tribe to Mizoram. I would like to thank Quality Council of India for carrying out the study effectively and comprehensively. At the same time, I would like to express my gratitude to Hon’ble Governor of Mizoram Lt. Gen. (Retd.) Nirbhay Sharma, Mr. Mahesh Singla, IPS, Advisor (North-East), Ministry of Home Affairs, Ms. Saumya Gupta, IAS, Director of Education, Delhi Government (Ex. District Magistrate, North Tripura), State Government of Tripura and District Authorities of North Tripura for their support and valuable inputs during the process and making it a success. -

Table of Contents Chapter 1

Table of Contents Chapter 1 ......................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Origin and Migration ........................................................................................ 2 1.2. Geographical and Demographic distribution ................................................... 3 1.3. Linguistic affiliation........................................................................................... 4 1.4. Dialectal variations ........................................................................................... 7 1.5. Cultural Background and Literary ..................................................................... 8 1.5.1. Literary background .................................................................................... 17 1.6. Data and Methodology ................................................................................... 18 Chapter 2 ....................................................................................................................... 19 Review of Literature .................................................................................................. 19 Chapter 3 ....................................................................................................................... 21 3. Phonemic inventory ............................................................................................. -

Revision Worksheet A. One Sentence Question: 1. Write the Name of Two Ethnic Groups of Hilly Areas. 2. Write the Name of Two

Subject: Bangladesh & Global Studies Day--8 Class: Five Samia Laboni rd 3 Term Syllabus: Date: 14-10-2020, Wednesday Revision Worksheet Chapter- 11: Ethnic Groups in Bangladesh Topic-1: The Garo A. One sentence Question: 1. Write the name of two ethnic groups of hilly areas. 2. Write the name of two ethnic groups in Bangladsh who have martiarchal society. 3. How many years ago did the Garo migrate to Bangladesh? 4. What language do the Garos speak? 5. What is the name of the traditional religion of the Garos? 6. What is the traditional dress of the Garo women? 7. What is ‘Nokmandi’ 8. What is the name of the sun god of the Garo? B. Creative Question: 1. Write 2 names of ethnic groups. What is the name of Garos native language? Write three sentences about their abode. 2. What is the traditional festival of the Garo? Why do they celebrate it? Write 4 sentences about their festivals. (2018) 3. How many years ago did the Garo start living in the country? Which language do they speak in? Write 3 sentences about their housing. (2015) Prepared by: Samia Laboni Class: Five Subject: BGS, Chapter-11 Topic-1,2,3,4,5-- Day-8, Revision Work sheet 4. What is the name of the traditional religion of the Garos? What is the name of their language? Write 3 sentences about their social system. (2015) Answer Sheet-1 A. One Sentence Question Answer: 1) Two ethnic groups of hilly areas are: the Garo and the Khasi. 2) Two ethnic groups in Bangladsh who have martiarchal society are: the Garo and the Khasi. -

2021081046.Pdf

Samuxchana Vc Biock Kutcha house beneficiary list under Kakraban PD Answe Father Category APSWANI DEBBARMA TR1153198 SUBHASH DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes RATAN KUMAR MURASING TR1128768 MANGALPAD MURASING Kutcha Wall Yes TR1128773 AMAR DEBBARMA ANANDA DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes GUU PRASAD DEBBARMA Yes TR1177025 |MANYA LAL DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall TR1177028 HALEM MIA MNOHAR ALI Kutcha Wal Yes GURU PRASAD DEBBARMA Kutcha Nall TR1212148 SUNIL DEBBARMA Yes SURENDRA DEBBARMA Yes TR1128767 CHANDRA MANI DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall TR1235047 SADHANI DEBBARMA RABI TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes Kutcha Wall Yes TR1212144 JOY MOHAN DEBBARMA ARANYA PADA DEBBARMA RUHINI KUMAR DEB8ARMA Kutcha Wall Yes 10 TR1279857 HARIPADA DEBBARMA 11 TRL279860 SURJAYA MANIK DEBBARMA SURESH DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes SHANTA KUMAR TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes 12 TR1200564 KRISHNAMANI TRIPURA 1258729 BIRAN MANI TRIPURA MALINDRA TRIPURA Kutcha Wall Yes Kutcha Wall 14 TR1165123 SURESH DEBBARMA BISHNU HARI DEBBARMA Yes 128769 PURNA MOHAN DEBBARMA SURENDRA DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall 1246344 GOURANGA DEBBARMA GURU PRASAD DEBBARMA Kutcha Wali Yes 17 RL140 83 KANTI BALA NOATIA SAHADEB DEBBARMA Kutcha Wa!l Yes 18 290885 BINAY DEBBARMA HACHUBROY DEBBARMA Kutcha Wali Yes 77024 SUKHCHANDRA MURASING MANMOHAN MURASING Kutcha Wall es 20 T1188838 SUMANGAL DEBBARMA JAINTHA KUMAR DEBBARMA Kutcha Wall Yes 2 T290883 PURRNARAY NOYATIYA DURRBA CHANDRA NOYATIYA Kutcha Wall Yes 212143 SHUKURAN!MURASING KRISHNA KUMAR MURASING Kutcha Wall Yes 279859 BAISHAKH LAKKHI MURASINGH PATHRAI MURASINGH Kutcha Wall Yes 128771 PULIN DEBBARMA -

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples' Issues

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues Republic of India Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues REPUBLIC OF INDIA Submitted by: C.R Bijoy and Tiplut Nongbri Last updated: January 2013 Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations ‗developed‘ and ‗developing‘ countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. All rights reserved Table of Contents Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples‘ Issues – Republic of India ......................... 1 1.1 Definition .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Scheduled Tribes ......................................................................................... 4 2. Status of scheduled tribes ...................................................................................... 9 2.1 Occupation ........................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Poverty .......................................................................................................... -

Minority Languages in India

Thomas Benedikter Minority Languages in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India ---------------------------- EURASIA-Net Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues 2 Linguistic minorities in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India Bozen/Bolzano, March 2013 This study was originally written for the European Academy of Bolzano/Bozen (EURAC), Institute for Minority Rights, in the frame of the project Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues (EURASIA-Net). The publication is based on extensive research in eight Indian States, with the support of the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano and the Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata. EURASIA-Net Partners Accademia Europea Bolzano/Europäische Akademie Bozen (EURAC) – Bolzano/Bozen (Italy) Brunel University – West London (UK) Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität – Frankfurt am Main (Germany) Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group (India) South Asian Forum for Human Rights (Nepal) Democratic Commission of Human Development (Pakistan), and University of Dhaka (Bangladesh) Edited by © Thomas Benedikter 2013 Rights and permissions Copying and/or transmitting parts of this work without prior permission, may be a violation of applicable law. The publishers encourage dissemination of this publication and would be happy to grant permission. -

Portrait of Population, Tripura

CENS US OF INDIA 1971 TRIPURA a portrait of pop u I a t ion A. K. BHATTACHARYYA 0/ the Tripura Civil Service Director of Census 'Operations TRIPURA Crafty mEn condemn studies and principles thereof Simple men admire them; and wise men use them. FRANCIS BACON ( i ) CONTENTS FOREWORD PREFACE ix CHAPTER I INTRODUcrORY Meaning of Cemu;-Historical perspective-Utility of Census-Historical background and Gazetteer of the State Planning of Census-Housing Census-Census-ta1<ing Organisa- tion and Machinery 1-105 II HOW MANY ARE WE? HOW ARE WE DISTRIBUTED AND BY HOW MUCH ARE OUR NUMBERS GROWING f Demography, the science of population-Population growth and its components-Sex and age composition-Sex ratio Distribution of age in Census data--Life Table from Census age data-A few refined measures of fertility-Decadal growth rates for Indian States-Size of India's population in contrast to some other countries-Size and distribution of population of Tripura in comparison with other States-Density of popula tion-Residential Houses and Size of household--Asian popula tion-findings of ECAFE Study-Growth rate of population in Tripura-Role of Migration in the Growth of population in Tripura 16-56 UI VILLAGE DWELLERS AND TOWN DWELLERS Growth story of village and town-Relationship among the dwellers of Tripura--Cultivable area available in Tripura Criteria for distinguishing Urban and Rural in different countries and in India-Distinction between vill.lge community and city community-Distribution of villages in Tripura-Level of urbanisation in Tripura-Concept of Standard Urban Area (SUA)-Urban Agglomeration. -

The State of Art of Tribal Studies an Annotated Bibliography

The State of Art of Tribal Studies An Annotated Bibliography Dr. Nupur Tiwary Associate Professor in Political Science and Rural Development Head, Centre of Excellence (CoE) for Tribal Affairs Contact Us: Centre of Tribal Research and Exploration, Indian Institute of Public Administration, Indraprastha Estate, Ring Road, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi, Delhi 110002 CENTRE OF TRIBAL RESEARCH & EXPLORATION (COTREX) Phone: 011-23468340, (011)8375,8356 (A Centre of Excellence under the aegis of Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India) Fax: 011-23702440 INDIAN INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Email: [email protected] NUP 9811426024 The State of Art of Tribal Studies An Annotated Bibliography Edited by: Dr. Nupur Tiwary Associate Professor in Political Science and Rural Development Head, Centre of Excellence (CoE) for Tribal Affairs CENTRE OF TRIBAL RESEARCH & EXPLORATION (COTREX) (A Centre of Excellence under Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India) INDIAN INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION THE STATE OF ART OF TRIBAL STUDIES | 1 Acknowledgment This volume is based on the report of the study entrusted to the Centre of Tribal Research and Exploration (COTREX) established at the Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA), a Centre of Excellence (CoE) under the aegis of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA), Government of India by the Ministry. The seed for the study was implanted in the 2018-19 action plan of the CoE when the Ministry of Tribal Affairs advised the CoE team to carried out the documentation of available literatures on tribal affairs and analyze the state of art. As the Head of CoE, I‘d like, first of all, to thank Shri.