An Assessment of Plant Diversity in Home Gardens of Reang Community of Tripura

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nitrogen Containing Volatile Organic Compounds

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Nitrogen containing Volatile Organic Compounds Verfasserin Olena Bigler angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Pharmazie (Mag.pharm.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 996 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Pharmazie Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. Gerhard Buchbauer Danksagung Vor allem lieben herzlichen Dank an meinen gütigen, optimistischen, nicht-aus-der-Ruhe-zu-bringenden Betreuer Herrn Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. Gerhard Buchbauer ohne dessen freundlichen, fundierten Hinweisen und Ratschlägen diese Arbeit wohl niemals in der vorliegenden Form zustande gekommen wäre. Nochmals Danke, Danke, Danke. Weiteres danke ich meinen Eltern, die sich alles vom Munde abgespart haben, um mir dieses Studium der Pharmazie erst zu ermöglichen, und deren unerschütterlicher Glaube an die Fähigkeiten ihrer Tochter, mich auch dann weitermachen ließ, wenn ich mal alles hinschmeissen wollte. Auch meiner Schwester Ira gebührt Dank, auch sie war mir immer eine Stütze und Hilfe, und immer war sie da, für einen guten Rat und ein offenes Ohr. Dank auch an meinen Sohn Igor, der mit viel Verständnis akzeptierte, dass in dieser Zeit meine Prioritäten an meiner Diplomarbeit waren, und mein Zeitbudget auch für ihn eingeschränkt war. Schliesslich last, but not least - Dank auch an meinen Mann Joseph, der mich auch dann ertragen hat, wenn ich eigentlich unerträglich war. 2 Abstract This review presents a general analysis of the scienthr information about nitrogen containing volatile organic compounds (N-VOC’s) in plants. -

TAXON:Costus Malortieanus H. Wendl. SCORE:7.0 RATING:High Risk

TAXON: Costus malortieanus H. SCORE: 7.0 RATING: High Risk Wendl. Taxon: Costus malortieanus H. Wendl. Family: Costaceae Common Name(s): spiral flag Synonym(s): Costus elegans Petersen spiral ginger stepladder ginger Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 2 Aug 2017 WRA Score: 7.0 Designation: H(HPWRA) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Perennial Herb, Ornamental, Shade-Tolerant, Rhizomatous, Bird-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans y=1, n=0 n 408 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems y=1, n=0 n 409 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle y=1, n=0 y Creation Date: 2 Aug 2017 (Costus malortieanus H. -

A Journal on Taxonomic Botany, Plant Sociology and Ecology

A JOURNAL ON TAXONOMIC BOTANY, PLANT SOCIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY ISSN 0034 – 365 X REINWARDTIA 13 (5) REINWARDTIA A JOURNAL ON TAXONOMIC BOTANY, PLANT SOCIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY Vol. 13(5): 391–455, December 20, 2013 Chief Editor Kartini Kramadibrata (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Editors Dedy Darnaedi (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Tukirin Partomihardjo (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Joeni Setijo Rahajoe (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Marlina Ardiyani (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Topik Hidayat (Indonesia University of Education, Indonesia) Eizi Suzuki (Kagoshima University, Japan) Jun Wen (Smithsonian Natural History Museum, USA) Managing Editor Himmah Rustiami (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Secretary Endang Tri Utami Layout Editor Deden Sumirat Hidayat Illustrators Subari Wahyudi Santoso Anne Kusumawaty Reviewers David Middleton (Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, UK), Eko Baroto Walujo (LIPI, Indonesia), Ferry Slik (Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, China), Henk Beentje (Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, UK), Hidetoshi Nagamasu (Kyoto Universi- ty, Japan), Kuswata Kartawinata (LIPI, Indonesia), Mark Hughes (Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, UK), Martin Callmander (Missouri Botanic Gardens, USA), Michele Rodda (Singapore Botanic Gardens, Singapore), Mien A Rifai (AIPI, Indonesia), Rugayah (LIPI, Indonesia), Ruth Kiew (Forest Research Institute of Malaysia, Malaysia). Correspondence on editorial matters and subscriptions for Reinwardtia should be addressed to: HERBARIUM BOGORIENSE, BOTANY DIVISION, RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY– LIPI, CIBINONG 16911, INDONESIA E-mail: [email protected] Cover images: Begonia hooveriana Wiriad. spec. nov. REINWARDTIA Vol 13, No 5, pp: 433−439 PANDAN (PANDANACEAE) IN FLORES ISLAND, EAST NUSA TENGGA- RA, INDONESIA: AN ECONOMIC-BOTANICAL STUDY Received August 02, 2012; accepted October 11, 2013 SITI SUSIARTI Herbarium Bogoriense, Botany Division, Research Center for Biology-LIPI, Cibinong Science Center, Jl. Raya Jakarta-Bogor Km. -

Committee on the Welfare of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (2010-2011)

SCTC No. 737 COMMITTEE ON THE WELFARE OF SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES (2010-2011) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) TWELFTH REPORT ON MINISTRY OF TRIBAL AFFAIRS Examination of Programmes for the Development of Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PTGs) Presented to Speaker, Lok Sabha on 30.04.2011 Presented to Lok Sabha on 06.09.2011 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 06.09.2011 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI April, 2011/, Vaisakha, 1933 (Saka) Price : ` 165.00 CONTENTS PAGE COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE ................................................................. (iii) INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ (v) Chapter I A Introductory ............................................................................ 1 B Objective ................................................................................. 5 C Activities undertaken by States for development of PTGs ..... 5 Chapter II—Implementation of Schemes for Development of PTGs A Programmes/Schemes for PTGs .............................................. 16 B Funding Pattern and CCD Plans.............................................. 20 C Amount Released to State Governments and NGOs ............... 21 D Details of Beneficiaries ............................................................ 26 Chapter III—Monitoring of Scheme A Administrative Structure ......................................................... 36 B Monitoring System ................................................................. 38 C Evaluation Study of PTG -

Bru-Reang-Final Report 23:5

Devising Pathways for Appropriate Repatriation of Children of Bru-Reang Community Ms. Stuti Kacker (IAS) Chairperson National Commission for Protection of Child Rights The National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) emphasizes the principle of universality and inviolability of child rights and recognises the tone of urgency in all the child related policies of the country. It believes that it is only in building a larger atmosphere in favour of protection of children’s rights, that children who are targeted become visible and gain confidence to access their entitlements. Displaced from their native state of Mizoram, Bru community has been staying in the make-shift camps located in North Tripura district since 1997 and they have faced immense hardship over these past two decades. Hence, it becomes imperative for the National Commission of Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) to ensure that the legal and constitutional rights of children of this community are protected. For the same purpose, NCPCR collaborated with QCI to conduct a study to understand the living conditions in the camps of these children and devise a pathway for the repatriation and rehabilitation of Bru-Reang tribe to Mizoram. I would like to thank Quality Council of India for carrying out the study effectively and comprehensively. At the same time, I would like to express my gratitude to Hon’ble Governor of Mizoram Lt. Gen. (Retd.) Nirbhay Sharma, Mr. Mahesh Singla, IPS, Advisor (North-East), Ministry of Home Affairs, Ms. Saumya Gupta, IAS, Director of Education, Delhi Government (Ex. District Magistrate, North Tripura), State Government of Tripura and District Authorities of North Tripura for their support and valuable inputs during the process and making it a success. -

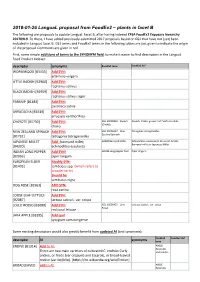

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

Periodic Table of Herbs 'N Spices

Periodic Table of Herbs 'N Spices 11HH 1 H 2 HeHe Element Proton Element Symbol Number Chaste Tree Chile (Vitex agnus-castus) (Capsicum frutescens et al.) Hemptree, Agnus Cayenne pepper, Chili castus, Abraham's balm 118Uuo Red pepper 33LiLi 44 Be 5 B B 66 C 7 N 7N 88O O 99 F 1010 Ne Ne Picture Bear’s Garlic Boldo leaves Ceylon Cinnamon Oregano Lime (Allium ursinum) (Peumus boldus) (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) Nutmeg Origanum vulgare Fenugreek Lemon (Citrus aurantifolia) Ramson, Wild garlic Boldina, Baldina Sri Lanka cinnamon (Myristica fragrans) Oregan, Wild marjoram (Trigonella foenum-graecum) (Citrus limon) 11 Na Na 1212 Mg Mg 1313 Al Al 1414 Si Si 1515 P P 16 S S 1717 Cl Cl 1818 Ar Ar Common Name Scientific Name Nasturtium Alternate name(s) Allspice Sichuan Pepper et al. Grains of Paradise (Tropaeolum majus) (Pimenta dioica) (Zanthoxylum spp.) Perilla (Aframomum melegueta) Common nasturtium, Jamaica pepper, Myrtle Anise pepper, Chinese (Perilla frutescens) Guinea grains, Garden nasturtium, Mugwort pepper, Pimento, pepper, Japanese Beefsteak plant, Chinese Savory Cloves Melegueta pepper, Indian cress, Nasturtium (Artemisia vulgaris) Newspice pepper, et al. Basil, Wild sesame (Satureja hortensis) (Syzygium aromaticum) Alligator pepper 1919 K K 20 Ca Ca 2121 Sc Sc 2222 Ti Ti 23 V V 24 Cr Cr 2525 Mn Mn 2626 Fe Fe 2727 Co Co 2828 Ni Ni 29 Cu Cu 3030 Zn Zn 31 Ga Ga 3232 Ge Ge 3333As As 34 Se Se 3535 Br Br 36 Kr Kr Cassia Paprika Caraway (Cinnamomum cassia) Asafetida Coriander Nigella Cumin Gale Borage Kaffir Lime (Capsicum annuum) (Carum carvi) -

Petiole Usually Stipules at the Base

Umbelliferae P. Buwalda Groningen) Annual or perennial herbs, never woody shrubs (in Malaysia). Stems often fur- rowed and with soft pith. Leaves alternate along the stems, often also in rosettes; petiole usually with a sheath, sometimes with stipules at the base; lamina usually much divided, sometimes entire. Flowers polygamous, in simple or compound um- bels, sometimes in heads, terminal or leaf-opposed, beneath with or without in- volucres and involucels. Calyx teeth 5, often obsolete. Petals 5, alternate with the calyx teeth, equal or outer ones of the inflorescence enlarged, entire or more or less divided, often with inflexed tips, inserted below the epigynous disk. Stamens alter- nate with the petals, similarly inserted. Disk 2-lobed, free from the styles or con- fluent with their thickened base, forming a stylopodium. Ovary inferior; styles 2. Fruits with 2 one-seeded mericarps, connected by a narrow or broad junction (commissure) in fruit separating, leaving sometimes a persistent axis (carpophore) either entire or splitting into 2 halves; mericarps with 5 longitudinal ribs, 1 dorsal rib at the back of the mericarp, 2 lateral ribs at the commissure; 2 intermediate ribs between the dorsal and the lateral ones; sometimes with secondary ribs be- without fascicular often vittae in tween the primary ones, these bundles; the ridges between the ribs or under the secondary ribs, and in the commissure, seldom under the primary ribs. Numerous Distr. genera and species, all over the world. The representatives native in Malaysia belong geographically to five types. (1) Ubiquitous genera (Hydrocotyle, Centella, Oenanthe); one species, & Hydrocotyle vulgaris, shows a remarkable disjunction, occurring in Europe N. -

INDEX for 2011 HERBALPEDIA Abelmoschus Moschatus—Ambrette Seed Abies Alba—Fir, Silver Abies Balsamea—Fir, Balsam Abies

INDEX FOR 2011 HERBALPEDIA Acer palmatum—Maple, Japanese Acer pensylvanicum- Moosewood Acer rubrum—Maple, Red Abelmoschus moschatus—Ambrette seed Acer saccharinum—Maple, Silver Abies alba—Fir, Silver Acer spicatum—Maple, Mountain Abies balsamea—Fir, Balsam Acer tataricum—Maple, Tatarian Abies cephalonica—Fir, Greek Achillea ageratum—Yarrow, Sweet Abies fraseri—Fir, Fraser Achillea coarctata—Yarrow, Yellow Abies magnifica—Fir, California Red Achillea millefolium--Yarrow Abies mariana – Spruce, Black Achillea erba-rotta moschata—Yarrow, Musk Abies religiosa—Fir, Sacred Achillea moschata—Yarrow, Musk Abies sachalinensis—Fir, Japanese Achillea ptarmica - Sneezewort Abies spectabilis—Fir, Himalayan Achyranthes aspera—Devil’s Horsewhip Abronia fragrans – Sand Verbena Achyranthes bidentata-- Huai Niu Xi Abronia latifolia –Sand Verbena, Yellow Achyrocline satureoides--Macela Abrus precatorius--Jequirity Acinos alpinus – Calamint, Mountain Abutilon indicum----Mallow, Indian Acinos arvensis – Basil Thyme Abutilon trisulcatum- Mallow, Anglestem Aconitum carmichaeli—Monkshood, Azure Indian Aconitum delphinifolium—Monkshood, Acacia aneura--Mulga Larkspur Leaf Acacia arabica—Acacia Bark Aconitum falconeri—Aconite, Indian Acacia armata –Kangaroo Thorn Aconitum heterophyllum—Indian Atees Acacia catechu—Black Catechu Aconitum napellus—Aconite Acacia caven –Roman Cassie Aconitum uncinatum - Monkshood Acacia cornigera--Cockspur Aconitum vulparia - Wolfsbane Acacia dealbata--Mimosa Acorus americanus--Calamus Acacia decurrens—Acacia Bark Acorus calamus--Calamus -

The State of Art of Tribal Studies an Annotated Bibliography

The State of Art of Tribal Studies An Annotated Bibliography Dr. Nupur Tiwary Associate Professor in Political Science and Rural Development Head, Centre of Excellence (CoE) for Tribal Affairs Contact Us: Centre of Tribal Research and Exploration, Indian Institute of Public Administration, Indraprastha Estate, Ring Road, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi, Delhi 110002 CENTRE OF TRIBAL RESEARCH & EXPLORATION (COTREX) Phone: 011-23468340, (011)8375,8356 (A Centre of Excellence under the aegis of Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India) Fax: 011-23702440 INDIAN INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Email: [email protected] NUP 9811426024 The State of Art of Tribal Studies An Annotated Bibliography Edited by: Dr. Nupur Tiwary Associate Professor in Political Science and Rural Development Head, Centre of Excellence (CoE) for Tribal Affairs CENTRE OF TRIBAL RESEARCH & EXPLORATION (COTREX) (A Centre of Excellence under Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India) INDIAN INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION THE STATE OF ART OF TRIBAL STUDIES | 1 Acknowledgment This volume is based on the report of the study entrusted to the Centre of Tribal Research and Exploration (COTREX) established at the Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA), a Centre of Excellence (CoE) under the aegis of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA), Government of India by the Ministry. The seed for the study was implanted in the 2018-19 action plan of the CoE when the Ministry of Tribal Affairs advised the CoE team to carried out the documentation of available literatures on tribal affairs and analyze the state of art. As the Head of CoE, I‘d like, first of all, to thank Shri. -

The Genus Amorphophallus

The Genus Amorphophallus (Titan Arums) Origin, Habit and General Information The genus Amorphophallus is well known for the famous Amorphophallus titanum , commonly known as "Titan Arum". The Titan Arum holds the plant world record for an unbranched single inflorescence. The infloresence eventually may reach up to three meters and more in height. Besides this oustanding species more than 200 Amorphophallus species have been described - and each year some more new findings are published. A more or less complete list of all validly described Amorphophallus species and many photos are available from the website of the International Aroid Society (http://www.aroid.org) . If you are interested in this fascinating genus, think about becoming a member of the International Aroid Society! The International Aroid Society is the worldwide leading society in aroids and offers a membership at a very low price and with many benefits! A different website for those interested in Amorphophallus hybrids is: www.amorphophallus-network.org This page features some awe-inspiring new hybrids, e.g. Amorphophallus 'John Tan' - an unique and first time ever cross between Amorphophallus variabilis X Amorphophallus titanum ! The majority of Amorphophallus species is native to subtropical and tropical lowlands of forest margins and open, disturbed spots in woods throughout Asia. Few species are found in Africa (e.g. Amorphophallus abyssinicus , from West to East Africa), Australia (represented by a single species only, namely Amorphophallus galbra , occuring in Queensland, North Australia and Papua New Guinea), and Polynesia respectively. Few species, such as Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Madagascar to Polynesia), serve as a food source throughout the Asian region. -

35 Chapter 2 INTER-ETHNIC CONFLICTS in NORTH EAST

Chapter 2 INTER-ETHNIC CONFLICTS IN NORTH EAST INDIA India as a whole has about 4,635 communities comprising 2,000 to 3,000 caste groups, about 60,000 of synonyms of titles and sub-groups and near about 40,000 endogenous divisions (Singh 1992: 14-15). These ethnic groups are formed on the basis of religion (Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Christian, Jain, Buddhist, etc.), sect (Nirankari, Namdhari and Amritdhari Sikhs, Shia and Sunni Muslims, Vaishnavite, Lingayat and Shaivite Hindus, etc.), language (Assamese, Bengali, Manipuri, Hindu, etc.), race (Mongoloid, Caucasoid, Negrito, etc.), caste (scheduled tribes, scheduled castes, etc.), tribe (Naga, Mizo, Bodo, Mishing, Deori, Karbi, etc.) and others groups based on national minority, national origin, common historical experience, boundary, region, sub-culture, symbols, tradition, creed, rituals, dress, diet, or some combination of these factors which may form an ethnic group or identity (Hutnik 1991; Rastogi 1986, 1993). These identities based on religion, race, tribe, language etc characterizes the demographic pattern of Northeast India. Northeast India has 4,55,87,982 inhabitants as per the Census 2011. The communities of India listed by the „People of India‟ project in 1990 are 5,633 including 635 tribal groups, out of which as many as 213 tribal groups and surprisingly, 400 different dialects are found in Northeast India. Besides, many non- tribal groups are living particularly in plain areas and the ethnic groups are formed in terms of religion, caste, sects, language, etc. (Shivananda 2011:13-14). According to the Census 2011, 45587982 persons inhabit Northeast India, out of which as much as 31169272 people (68.37%) are living in Assam, constituting mostly the non-tribal population.