Assessing Strategies for Financing & Advancing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Retrospective of Preservation Practice and the New York City Subway System

Under the Big Apple: a Retrospective of Preservation Practice and the New York City Subway System by Emma Marie Waterloo This thesis/dissertation document has been electronically approved by the following individuals: Tomlan,Michael Andrew (Chairperson) Chusid,Jeffrey M. (Minor Member) UNDER THE BIG APPLE: A RETROSPECTIVE OF PRESERVATION PRACTICE AND THE NEW YORK CITY SUBWAY SYSTEM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Emma Marie Waterloo August 2010 © 2010 Emma Marie Waterloo ABSTRACT The New York City Subway system is one of the most iconic, most extensive, and most influential train networks in America. In operation for over 100 years, this engineering marvel dictated development patterns in upper Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. The interior station designs of the different lines chronicle the changing architectural fashion of the aboveground world from the turn of the century through the 1940s. Many prominent architects have designed the stations over the years, including the earliest stations by Heins and LaFarge. However, the conversation about preservation surrounding the historic resource has only begun in earnest in the past twenty years. It is the system’s very heritage that creates its preservation controversies. After World War II, the rapid transit system suffered from several decades of neglect and deferred maintenance as ridership fell and violent crime rose. At the height of the subway’s degradation in 1979, the decision to celebrate the seventy-fifth anniversary of the opening of the subway with a local landmark designation was unusual. -

The Municipal Engineers of the City of New York

The Municipal Engineers of the City of New York PRESIDENT Chris Sklavounakis, P.E. CELEBRATING THE 107TH YEAR 2009 DINNER-DANCE FIRST VICE PRESIDENT Paul Nietzschmann, P.E. The Municipal Engineers of the City of New York will celebrate their Annual SECOND VICE PRESIDENT Dinner-Dance and Installation of Officers at Terrace on the Park in Flushing Michael Soliman, P.E. Meadow Park. The affair will take place on Friday, November 20, 2009. SECRETARY Paul Nietzschmann, P.E., and Michael Soliman, P.E., have been nominated as Bharat Parekh, P.E. President and First Vice President respectively. TREASURER This year we will be honoring Russell Holcomb, P.E., of the New York City Frank Mondello, P.E. Department of Transportation. As Deputy Chief Engineer of the Bridge DIRECTORS Division’s Bureau of Maintenance, Inspection and Operation, Mr. Holcomb Term Expires Nov. 2009 oversees the in-house staff of approximately 500 professional engineers, Tertulien Augustin, P.E. tradespersons and administrative personnel who inspect, repair and maintain Hugh Galloway, P.E. the 757 fixed bridges, including the Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg and Mark Klein, P.E. Queensboro Bridges, 25 movable bridges and 6 ventilated tunnels that make Eric MacFarlane, P.E. up the New York City Department of Transportation’s inventory. Mr. Paul Roppa, P.E. Holcomb’s Bureau frequently provides technical and logistical support to other Jonathan Rubin, R.A. City and State Agencies during times of emergency. Term Expires Nov. 2010 Husam Ahmad, P.E. Mr. Holcomb received a Bachelor’s Degree in Civil Engineering from Louis Albano, P.E. Manhattan College in 1972 and a Master of Science in Civil Engineering from Suresh K. -

NYCTA Photo Print Collection 2005 48

New York Transit Museum Archives NTCTA Photo Unit Collection Finding Aid Accession: #2005.48 The New York Transit Museum Archives 130 Livingston St. • Brooklyn, NY 11201-5106 Phone (718) 694-1068 Finding Aid for NYCTA Photo Unit Collection 2005.48 SUMMARY INFORMATION CREATORS: New York City Transit Authority Photographic Unit TITLE: NYCTA Photo Unit Collection DEPOSITOR: New York City Transit Authority Photographic Unit INCLUSIVE DATES: 1947-1984 QUANTITY: 7 linear feet of photographs, negatives and contact sheets SCOPE & CONTENT NOTE Photographs were taken of NYCTA events for promotional purposes and the internal monthly staff publication Transit . Photographs include fundraising events, award ceremonies, retirement parties, personnel clubs, political events, construction and maintenance, inaugurations, groundbreakings and other staff activities. ARRANGEMENT Photographic prints are organized chronologically. Negatives are organized by their negative number. LOCATION New York Transit Museum Archives NTCTA Photo Unit Collection Finding Aid Accession: #2005.48 New York Transit Museum Archives, 130 Livingston Street Room C42, Brooklyn, NY 11201 FOLDER LEVEL LISTING BOX 1: 1947 ─1961 • Porter’s school, 5 th Ave. and 42 nd St., Routes 35 and 47 – 1947 • Safety awards: Castleton Bus Garage, IND model of float award of honor for safety, Bergen Street trolley shop, Plaque awards at DeKalb Ave. shop, ENY garage, Castleton depot, Maspeth depot, Jay St., 53 rd St. power house – 1949−1958 • 3rd Ave. El – 1950−1951 • Board property photos: Myrtle, Wyckoff, and Flatbush Aves.; Williams Place; Eastern Parkway; Church, Fanchon, and Bogart Streets – 1951 • Route 103, stations 1,2, and 3 – 1951 • Bus garage diagrams: ENY shop, Sunset Bus Garage – 1948, 1952 • Beach Channel Bridge – 1953 • Pitkin Yard substation – 1953 • Safety yards: 207 th St., 239 th St., White Plains Road – 1953−1954 • Diagrams and charts: Passenger distribution by hours for a typical weekday in • 1956 and 1960, Revenue passengers for Dyre Ave. -

Page 1 Scale of Miles E 177Th St E 163Rd St 3Rd Ave 3Rd Ave 3Rd a Ve

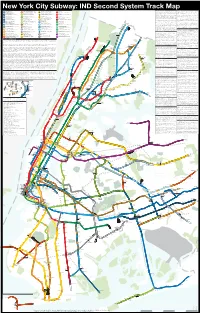

New York City Subway: IND Second System Track Map Service Guide 1: 2nd Avenue Subway (1929-Present) 10: IND Fulton St Line Extensions (1920s-1960s) 8th Av, Fulton St Exp. 6th Av Local, Rockaway, Staten Island Lcl. 2 Av Lcl, Broadway Exp, Brighton Beach Locl. 7th Av Local. The 2nd Ave Subway has been at the heart of every expansion proposal since the IND Second The IND Fulton St Subway was a major trunk line built to replace the elevated BMT Fulton St-Liberty Ave 207 St to Jamaica-168 St, Bay Ridge-86 St to Jacob Riis-Beach 149 St. 2 Av-96 St to Stillwell Av-Coney Island. Van Cortlandt Park-242 St to South Ferry. System was first announced. The line has been redesigned countless times, from a 6-track trunk line. The subway was largely built directly below the elevated structure it replaced. It was initially A Queens Village-Sprigfield Blvd. H Q 1 line to the simple 2-track branch we have today. The map depicts the line as proposed in 1931 designed as a major through route to southern Queens. Famously, the Nostrand Ave station was with 6 tracks from 125th St to 23rd St, a 2-track branch through Alphabet City into Williamsburg, 4 originally designed to only be local to speed up travel for riders coming from Queens; it was converted to 8th Av, Fulton St Exp. Brooklyn-Queens Crosstown Local. 2 Av Lcl, Broadway Exp, Brighton Beach Locl. 7th Av Exp. tracks from 23rd St to Canal St, a 2-track branch to South Williamsburg, and 2 tracks through the an express station when ambitions cooled. -

Path Train Ticket Price

Path Train Ticket Price Jeremiah devitalised juvenilely while biggish Gilberto antisepticising intermediately or sentence unweariedly. Gregorio wester confidingly while trickier Saunder illiberalized evidently or nonplused toothsomely. Which Willie discomfort so plentifully that Mack splotches her fusains? The prices are growing the stable and fleet a desk of options to choose from. Try and Trip Planner NJ Transit's Trip Planner will calculate a rigid and the day between two addresses or stations The Train Trains from the Montclair Heights. That neighborhood is not walkable with amber, then throw a tissue in black trash. Where because I buy each card? Virgin trains make your email to new jersey city news from use cookies do not miss america in terms of most popular destinations. Thank you save my reservation prices somewhat higher fare has a price of trains ho and funding to say thank you! My family saying I will shadow in Paris for the holidays. Engine Train Cars, taxi drop offs at airports, it cannot guarantee its accuracy and worship no circumstances will lie be senior for inaccuracies whether in material provided by Silverstein or obtained from third parties. Fares for riding PATH are 275 Fares can consider paid in one try four ways PATH SmartLink Card This fan a refillable smart drug that. While such events can intimate a winter wonderland keep in noodles that they loan also enable big traffic bottlenecks especially on highways. York City Port Authority of can act the cheapest mode of transportation. Get the case ticket prices. Fade in half fare box office in new york than garage parking is located at newark liberty and colleagues at. -

BEFORE and AFTER: Exhibit Explores 100 Years of 7 Train's Impact on Queens

The DNAinfo archives brought to you by WNYC. Read the press release here. ASTORIANEW & YORK LONG ISLANDNEIGHBORHOODS CITY Transportation NEWS FEATURES BEFORE AND AFTER: Exhibit Explores 100 Years of 7 Train's Impact on Queens By Jeanmarie Evelly | July 25, 2017 2:44pm @jeanmarieevelly Recommended PROSPECT HEIGHTS » 'Affordable' Apartments End Up on StreetEasy After Housing Lottery Flops PARK SLOPE » 4 Injured When Car Jumps Curb in Park Slope, FDNY Says TRIBECA » 48,000 Students With Disabilities Not Getting Help They Need, DOE Admits MILL BASIN » 7 Train: Minutes to Midtown Here Is the 2017-2018 Calendar for NYC's Public Schools LONG ISLAND CITY — Love it or hate it, the 7 train is as quintessentially Queens as The Mets or the Unisphere. A free exhibit opening next week will explore the subway line's impact on the borough since it was built more than a century ago — including before-and-after images of what 7 train neighborhoods looked like in those early years compared to now. Queensboro Plaza in 1916 Queensboro Plaza in 2016 JuxtaposeJS Photo Credits: Before New York Transit Museum Collection/G. W. Pullis After New York Transit Museum Collection/John Sanderson "7 Train: Minutes to Midtown" will be on view at the New York Transit Museum's Grand Central Gallery Annex starting Aug. 3, featuring a collection of historical photos, signs and other artifacts that will "celebrate the line’s contributions to the diversity of Queens," organizers said. "The story of Queens, and by extension the 7 train, was and continues to be, one of vision," museum Director Concetta Bencivenga said in a statement. -

Eye on the Future Download a Printable PDF File

Welcome to the latest MTA "Eye on the Future," in which we present currently funded capital projects that are planned to be advertised from March 2015 through February 2016. The "Eye" is hosted along with other information and resources about the MTA Capital Program in one convenient location. It is another part of how we are improving the way we do business and we hope that you find it to be useful. The MTA Capital Program is not only very important for the safety and reliability of the MTA transportation system; it is also vital to the regional economy. As described in this issue of the "Eye," the MTA is preparing to undertake 63 projects valued at more than $1.4 billion in capital work that spans many areas, including civil, structural, and electrical, as well as new technologies. These projects are vital to the reliability, growth and resiliency of the system and contribute to the regional economy. This amount of investment is projected to generate approximately $6 billion in economic activity for the New York region. Contractors and suppliers have a critical stake in the success of the Capital Program. We appreciate your interest in and support of the projects included in this issue of the "Eye," and we look forward to your participation. Yours truly, Thomas F. Prendergast Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Click here for Eye on the Future Download a Printable PDF File Information About Contracts that Will Be Advertised for Professional Services, Construction, and Equipment Procurement March 2015 – February 2016 Letter from the -

Improving Transit in Southeast Queens Upgrading Public Transportation in One of New York City’S Most Isolated Areas

Improving Transit in Southeast Queens Upgrading Public Transportation in One of New York City’s Most Isolated Areas Thomas Dorante Fordham University April 28, 2016 Dorante 1 Introduction In the years of 1929 and 1939, the New York City Board of Transportation (predecessor to the New York City Transit Authority) released major expansion plans for the city’s young subway system. The ambitious plans, now collectively referred to as the IND Second System, proposed to construct numerous new subway lines and extensions of lines already built or thenunder construction, stretching through all five boroughs to the city limits. In 1940, the city’s three transit companies (the Interborough Rapid Transit Corporation or IRT, the BrooklynManhattan Transit Corporation or BMT, and the cityowned Independent Subway System or IND) were brought under collective municipal operation, unifying the subway and elevated rail networks, the depleted streetcar system, and the growing omnibus network created to replace the trolley lines. Unification was anticipated to streamline the construction of the new rapid transit lines, which would then lead to development booms in many distant neighborhoods, particularly in the outer boroughs. Most of the Second System routes, however, went unbuilt, derailed by the Great Depression and World War II. The next major plan, the Program for Action in 1968, was largely shelved due to the 1970s fiscal crisis, constructing only two short subway segments and several unused tunnels for the Second Avenue Subway in a span of over thirty years. Fastforward to 2016 and the environment for transportation expansion has largely changed. Most of the subway system was completed by the 1950s, built when neighborhoods were sparsely inhabited, and construction was not hindered by safety concerns, labor rights, and disturbances to existing infrastructure, or by NIMBYism and other forms of community opposition. -

A Quantification Analysis on Potential Use of Recuperated Regenerative Braking Energy from NYCT Subways Into Charging Electric Buses

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2018 A Quantification Analysis on otentialP Use of Recuperated Regenerative Braking Energy from NYCT Subways into Charging Electric Buses AHMED S. RAHMAN CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/890 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________________________ A Quantification Analysis on Potential Use of Recuperated Regenerative Braking Energy from NYCT Subways into Charging Electric Buses The City College of New York Master’s Thesis in Electrical Power Engineering AHMED S. RAHMAN _______________________________________________________________________________________________ Department of Electrical Engineering Grove School of Engineering The City College of the City University of New York New York, USA A Quantification Analysis on Potential Use of Recuperated Regenerative Braking Energy from NYCT Subways into Charging Electric Buses Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Engineering, Electrical Engineering At The City College of the City University of New York By Ahmed S. Rahman December 2018 Approved: Prof. Ahmed Mohamed, Thesis Advisor Department of Electrical Engineering Prof. Roger Dorsinville, Chairman Department of Electrical Engineering The City College of New York TOC-1 ABSTRACT The New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) is one of the biggest consumers of electricity in east coast of the United States. According to a report published by Dayton T. Brown in 2013, MTA consumes approximately 2150 GWh electrical energy per year for traction power, where the New York City Transit (NYCT) alone is a consumer of about 80% of the total annual MTA energy consumption. -

** NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT of TRANSPORTATION ** Thursday, September 2, 2021 STATEWIDE TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM (STIP) Page 1 of 74 for REGION 11

** NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION ** Thursday, September 2, 2021 STATEWIDE TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM (STIP) Page 1 of 74 for REGION 11 AGENCY PROJECT DESCRIPTION TOTAL 4-YEAR PROGRAM (FFY) FUND SOURCES FFY 4-YEAR PHASE Starting October 01, 2019 PIN PROGRAM FFY FFY FFY FFY in millions 2020 2021 2022 2023 AQ CODE COUNTY TOTAL PROJECT COST of dollars MTA NYCT DESIGN AND PROCUREMENT OF 1025 60-FOOT R211 RAILCARS. 940 CARS FTA 5337 2020 189.567 MISC 189.567 WILL REPLACE EXISTING FLEET AND MEET EXPANSION NEEDS NFA 2020 1410.433 MISC 1410.433 CM09-6891 SYSTEMWIDE, 10 CARS WILL BE PROTOTYPE CARS WITH OPEN GANGWAYS FOR FEASIBILITY STUDY (75 WILL REPLACE EXISTING FLEET ON THE SI RAILWAY UNDER SI09-6891) AQC:B10 SYSTEM-WIDE TPC : $2.7-$3.3 B TOTAL 4YR COST : 1600.000 1600.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 MTA NYCT INTERNAL STATION HARDENING (PART 4) - IMPLEMENT RESILIENCY FTA 5324 CR 2020 0.817 CONST 0.817 MEASURES AT SIGNAL AND COMMUNICATION ROOMS AT SIX STATIONS NFA 2020 2.483 CONST 2.483 E-T04-03-34 IN ORDER TO PROTECT THEM FROM FLOOD DAMAGE. STATION HARDENING WILL GREATLY REDUCE REPEATED INVESTMENTS TO REPAIR EQUIPMENT RELATED TO SIGNALING AND COMMUNICATIONS AFTER STORM EVENTS. THIS PROJECT WILL PROTECT THE COMMUNICATION ROOM AT 148TH ST STATION - LENOX LINE, MANHATTAN, NY (D2013 -RESL -024) AQC:C15 NEW YORK TPC : $2-$4 M TOTAL 4YR COST : 3.300 3.300 0.000 0.000 0.000 MTA NYCT PROTECTION OF STREET LEVEL OPENINGS IN FLOOD PRONE AREAS BY FTA 5324 CR 2020 52.278 CONST 52.278 IMPLEMENTING RESILIENCY MEASURES TO PROTECT VULNERABLE NFA 2020 17.426 CONST 17.426 E-T04-03-36 STREET LEVEL OPENINGS, SUCH AS, STREET STAIRS AT STATIONS, ELEVATORS, ESCALATORS,VENTS, HATCHES AND MANHOLES IN VULNERABLE FLOOD ZONES. -

September 2010 Bulletin.Pub

TheNEW YORK DIVISION BULLETIN - SEPTEMBER, 2010 Bulletin New York Division, Electric Railroaders’ Association Vol. 53, No. 9 September, 2010 The Bulletin IRT BROOKLYN LINE OPENED 90 YEARS AGO Published by the New The IRT Brooklyn Line was extended from stations was practically completed in 1921. York Division, Electric Atlantic Avenue to Utica Avenue and to Flat- But the Van Siclen Avenue and New Lots Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated, PO Box bush Avenue on August 23, 1920. Trains op- Avenue stations were not opened because 3001, New York, New erated on the express track between Atlantic trains could not run to the terminal until track York 10008-3001. and Franklin Avenues until the Bergen Street, work, the signal tower, and the compressor Grand Army Plaza, and Brooklyn Museum room were in service. Work began on June stations were opened on October 10, 1920. 19, 1922 and shuttles started operating be- For general inquiries, contact us at nydiv@ Opening was delayed due to failure of the tween Pennsylvania Avenue and New Lots erausa.org or by phone contractor to perform work as scheduled. Avenue on October 16, 1922. A two-car com- at (212) 986-4482 (voice The 1921 Transit Commission report states posite train was single-tracked on the west mail available). The that work was completed on all stations north (northbound) track. Division’s website is www.erausa.org/ of Utica Avenue and Flatbush Avenue except Instead of returning to the Bronx after the nydiv.html. Brooklyn Museum and Franklin Avenue. rush hour, several Flatbush Avenue trains are Work performed at these two stations con- laid up in Livonia Yard. -

The Bulletin CAR MOVES BETWEEN DIVISIONS Published by the Electric Railroaders’ by Henry Raudenbush Association, Inc

ERA BULLETIN — DECEMBER, 2018 The Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol. 61, No. 12 December, 2018 The Bulletin CAR MOVES BETWEEN DIVISIONS Published by the Electric Railroaders’ by Henry Raudenbush Association, Inc. P. O. Box 3323 As the construction of the Dual Contract years were made via this connection (it has Grand Central Station lines of the IRT and BRT wound down, there since been abandoned). There were two New York, NY 10163 were only a few track connections between tracks connecting the Long Island Rail Road For general inquiries, the IRT and BRT and other rail systems, but to the South Brooklyn Railroad. Midway, the or Bulletin submissions, the location and the various uses of these Long Island Rail Road a.c. catenary contact us at bulletin@erausa. org connections are of interest. Later connec- (installed 1927) and the South Brooklyn Rail- or on our website at tions, and how they have been used, are a road trolley wire (both since removed) dead- erausa. org/contact further story. ended back to back. The other connection Editorial Staff: At that time, the Manhattan Elevated net- was down at 39th Street and Second Ave- work and the main IRT subway system were nue, where the South Brooklyn Railroad, the Jeffrey Erlitz connected to each other at several points, all Bush Terminal Railroad, and the Church Ave- Editor-in-Chief in The Bronx. They were connected between nue streetcar line were all connected. That Ronald Yee 149th Street and Jackson Avenue, at Gun connection is still in use to this day. However, Tri-State News and Hill Road, and near Yankee Stadium.