Improving Transit in Southeast Queens Upgrading Public Transportation in One of New York City’S Most Isolated Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surface Water Supply of the United States 1958

Surface Water Supply of the United States 1958 Part 14. Pacific Slope Basins in Oregon and Lower Columbia River Basin Prepared under the direction of J. V. B. WELLS, Chief, Surface Water Branch GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1568 Prepared in cooperation with the States of Oregon and Washington and with other agencies UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1960 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. - Price $1 (paper cover) PREFACE This report was prepared by the Geological Survey in coopera tion with the States of Oregon and Washington and with other agen cies, by personnel of the Water Resources Division, L. B. Leopold, chief, under the general direction of J. V. B. Wells, chief, Surface Water Branch, and F. J. Flynn, chief, Basic Records Section. The data were collected and computed under supervision of dis trict engineers, Surface Water Branch, as follows: K. N. Phillips...............>....................................................................Portland, Oreg, F. M. Veatch .................................................................................Jacoma, Wash. Ill CALENDAR FOR WATER YEAR 1958 OCTOBER 1957 NOVEMBER 1957 DECEMBER 1957 5 M T W T F S S M T W T P S S M T W T P S 12345 1 2 1234567 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3456789 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 -

421 Marcus Garvey Boulevard Brooklyn, NY Bedford-Stuyvesant

RETAIL/RESTAURANT/MEDICAL/OFFICE SPACE 421 Marcus Garvey Boulevard Approx. 425 SF Brooklyn, NY Available for Lease Bedford-Stuyvesant Located Between Halsey Street and Macon Street Size Frontage Comments Transportation Approx. 425 SF – Ground Floor Approx. 13 FT on Marcus Garvey Compact space, perfect for 2017 Ridership Report quick service food, coffee, Blvd. Kingston-Throop Aves C Asking Rent juice bar, or similar. No vented Annual 2,085,536 cooking Upon Request Neighbors Weekday 6,564 Weekend 7,644 Brown Sugar, Tree House, Ideal for local retailers Formerly Tepache Mexican Grill, Bohaus Utica Avenue A C Located in a quickly The Doll House Coffee & Flowers, Summer Wine Annual 5,271,782 transforming retail corridor of Weekday 16,408 Bar & Kitchen, Olivino Wines, Possession Bed-Stuy Weekend 20,225 Macon Hardware, Cloud 9 Immediate Crepes, Community Deli, Fine Five short blocks from the C B15 15 Annual 6,494,369 Fare Supermarket, Zaca Cafe Subway at Kingston-Throop Ceiling Heights Weekday 19,827 8’ – Ground Floor Weekend 26,557 B26 26 Annual 2,920,409 Weekday 11,638 Contact our exclusive agents: Weekend 6,807 Scott Rothstein Ben Weiner B43 43 Annual 3,099,517 [email protected] [email protected] Weekday 9,832 718.704.1450 718.233.6565 Weekend 11,113 CLERMONT AVENUE CLERMONT VANDERBILT AVENUE VANDERBILT CLINTON AVENUE CLINTON WASHINGTON AVENUE WASHINGTON WAVERLY AVENUE WAVERLY CLASSON AVENUE CLASSON HALL STREET HALL GRAND AVENUE GRAND RYERSON STREET RYERSON STEUBEN STREET STEUBEN Smiling Faces Nursery School Nursery Faces Smiling Duncan’s Quality Fish Market Fish Quality Duncan’s Farmer in the Deli the in Farmer Yummy Tummy Chinese Restaurant Chinese Tummy Yummy Greene-ville Garden Greene-ville Polish Nails, Inc. -

DYCD After-School Programs

DYCD after-school programs PROGRAM TYPE PROGRAM SITE NAME After-School Programs Beacon IS 49 After-School Programs,Jobs & Internships,Youth In-School Youth Employment (ISY) Intermediate School 217 - Rafael Hernandez Employment School After-School Programs Out of School Time Building T 149 Reading & Writing,NDA Programs,Family Literacy Adolescent Literacy K 533- School for Democracy and Leadership 600 Kingston Avenue After-School Programs,NDA Programs,Youth High-School Aged Youth Voyagees Prepatory High School Educational Support Family Support,NDA Programs Housing AIDS Center of Queens County Jamaica Site Immigration Services,Immigrant Support Services Domestic Violence Program Jewish Board of Family and Children Services (JBFCS)-Genesis Immigration Services,Immigrant Support Services Domestic Violence Program Jewish Board of Family and Children Services - Horizons Immigration Services,Immigrant Support Services Legal Assistance Program Safe Horizon - Immigration Law Project Runaway & Homeless Youth Transitional Independent Living (TIL) Good Shepherd Services Runaway & Homeless Youth Transitional Independent Living (TIL) Green Chimneys Runaway & Homeless Youth Transitional Independent Living (TIL) Girls Educational & Mentoring Services, Inc. Runaway & Homeless Youth Transitional Independent Living (TIL) Inwood House Runaway & Homeless Youth Transitional Independent Living (TIL) SCO Family of Services Page 1 of 798 09/24/2021 DYCD after-school programs BOROUGH / COMMUNITY AGENCY Staten Island Jewish Community Center of Staten Island Bronx Simpson Street Development Association, Inc. Queens Rockaway Artist Alliance, Inc. Brooklyn CAMBA Queens Central Brooklyn Economic Development Corporation Queens St. Luke A.M.E Church Manhattan New York Legal Assistance Group (NYLAG) Brooklyn New York Legal Assistance Group (NYLAG) Manhattan,Bronx,Queens,Staten Island, Brooklyn Safe Horizon, Inc. Manhattan Good Shepherd Services Manhattan Green Chimneys Manhattan Girls Educational & Mentoring Services, Inc. -

Sicilian Eatery

SICILIAN EATERY Concrete is a casual dining experience located on the border of Brooklyn neighborhoods Bedford Stuyvesant + Bushwick. 917-886-9660 The 3,000 sq ft space has a capacity of 75, featuring an open kitchen, dining area, full bar with seating, and performance stage. 906 Broadway, Concrete’s menu includes a variety of plates from both Italian and American cuisines, Brooklyn NY 11206 in addition to a selection of Sicilian street food favorites. 906broadway The bar offers a selection of top shelf liquors, Sicilian wines, and local beers. @gmail.com The list of specialty cocktails are curated exclusively for Concrete, with all cocktail syrups made fresh + in house by our bartending staff. @concretebrooklyn Open June 2018, the space features artwork from both local and international artists, www. including a custom mural from artist Mike Lee on the building’s Stockton St side. concrete-brooklyn The live event calendar is set to premiere in Fall 2018. .com Currently serving dinner from 5p - 11p, with brunch available on weekends. Located at 906 Broadway, Brooklyn NY 11206, accessible by the J/M/Z trains at Myrtle-Broadway + the B46 bus. THE NEAREST TRAINS ARE THE M/J/Z LINES AT MYRTLE - BROADWAY, OR FLUSHING AVE. WE ARE A 14 MINUTE WALK FROM THE HALSEY L TRAIN STATION IN BUSHWICK. THE B46, B47, B54, M1, M119 (AT MYRTLE AVE), AND B15 (AT LEWIS AVE) HAVE ROUTES TO MYRTLE / BROADWAY JUNCTION, AND ARE WITHIN A 3-10 MINUTE WALK FROM CONCRETE’S LOCATION. High resolution images can be downloaded here: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/1upry4klu8zc8ll/AADVl9DsBLjDfT5-E4H1iezNa?dl=0 Interior and Exterior Space Photography: Leonardo Mascaro http://www.leonardomascaro.com Food + Drink Photography: Paul Quitoriano http://www.paulcrispin.com DOP GRADE PRODUCTS Dnominazione di Origine Protetta certification ensures that products are locally grown and packaged. -

Project Context

PIN X735.82 Van Wyck Expressway Capacity and Access Improvements to JFK Airport Project DDR/DEIS CHAPTER 2 Project Context PIN X735.82 Van Wyck Expressway Capacity and Access Improvements to JFK Airport Project DDR/DEIS Project Context 2.1 PROJECT HISTORY As part of a post-World War II $200-million development program, and in anticipation of an increased population size, the City of New York sought to expand its highway and parkway system to allow for greater movement throughout the five boroughs. The six-lane Van Wyck Expressway (VWE) was envisioned to help carry passengers quickly from the newly constructed Idlewild Airport (present-day John F. Kennedy International Airport [JFK Airport]) to Midtown Manhattan. In 1945, the City of New York developed a plan to expand the then-existing Van Wyck Boulevard into an expressway. The City of New York acquired the necessary land in 1946 and construction began in 1948, lasting until 1953. The Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) bridges for Jamaica Station, which were originally constructed in 1910, were reconstructed in 1950 to accommodate the widened roadway. The designation of the VWE as an interstate highway started with the northern sections of the roadway between the Whitestone Expressway and Kew Gardens Interchange (KGI) in the 1960s. By 1970, the entire expressway was a fully designated interstate: I-678 (the VWE). In 1998, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) began work on AirTrain JFK, an elevated automated guideway transit system linking downtown Jamaica to JFK Airport. AirTrain JFK utilizes the middle of the VWE roadway to create an unimpeded link, connecting two major transportation hubs in Queens. -

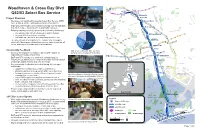

Woodhaven & Cross Bay Blvd Q52/53 Select Bus Service

Woodhaven & Cross Bay Blvd E F M T AV 75 St GRAND CENTRAL ROOSEVEL 78 St 7 BROADW Q52/53 Select Bus Service 61 St Whitney Av A Y Grand Av V Project Overview PKWY AN WYCK EXPY • Woodhaven/Cross Bay Boulevards Select Bus Service (SBS) Queens Blvd route is based on the existing Q52 and Q53 bus routes M LONG ISLAND EXPY • Important north/south transit corridor carrying over 30,000 daily LYN QUEENS EXPY Penelope Av bus riders in Queens along with heavy traffic volumes BROOK WOODHA • Existing roadway geometry presents the following challenges: PKWY GRAND CENTRAL » one-way bus trips can vary between 55 and 85 minutes AN AV Bus METROPOLIT VEN BL Metropolitan Av » long and difficult pedestrian crossings Stops F » high traffic speeds and heavy congestion at bottlenecks 18% VD E • The project goal is to transform the corridor into a complete Red Myrtle Av Lights In Motion J street with faster/more reliable bus service, safer streets for all Z 25% 57% V users, and improved traffic and local conditions Jamaica Av AN WYCK EXPY AV JAMAICA 91 Av AIR Community Feedback J V TR Split of all northbound Q53 bus trips: JACKIE ROBINSON PKWY A Z AIN JFK • Community engagement began in Spring 2014 and is an Q53 LTD buses are stopped ~half of time ATLANTIC 101 Av important part of project planning A Rockaway Blvd ROCKAW • DOT and MTA continues to work with a broad range of A CONDUIT AY BLVD AV Pitkin Av neighborhood stakeholders, residents and bus riders at design CROSS BA workshops, public forums and CAC meetings BELT PKWY • Key community feedback received at -

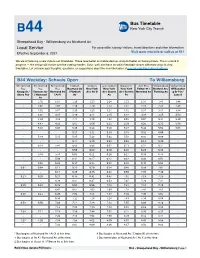

MTA B44 Bus Timetable

Bus Timetable B44 New York City Transit Sheepshead Bay - Williamsburg via Nostrand Av Local Service For accessible subway stations, travel directions and other information: Effective September 5, 2021 Visit www.mta.info or call us at 511 We are introducing a new style to our timetables. These read better on mobile devices and print better on home printers. This is a work in progress — the design will evolve over the coming months. Soon, we'll also have an online timetable viewer with more ways to view timetables. Let us know your thoughts, questions, or suggestions about the new timetables at new.mta.info/timetables-feedback. B44 Weekday: Schools Open To Williamsburg Sheepshead Sheepshead Sheepshead Flatbush Flatbush East Flatbush Crown Hts Bed-Stuy Williamsburg Williamsburg Bay Bay Bay Nostrand Av New York New York New York Fulton St / Bedford Av / Williamsbur Knapp St / Emmons Av Nostrand Av / Flatbush Av / Av D Av / Church Av / Eastern Nostrand Av Flushing Av g Br Plz / Shore Pky / Nostrand / Av U Av Av Py Lane 4 Av - 1:02 1:07 1:16 1:20 1:24 1:32 1:37 1:43 1:48 - 2:02 2:07 2:16 2:20 2:24 2:32 2:37 2:43 2:48 - 3:02 3:07 3:16 3:20 3:24 3:32 3:37 3:43 3:48 - 4:02 4:07 4:16 4:21 4:25 4:33 4:38 4:45 4:50 - 4:30 4:35 4:44 4:49 4:53 5:01 5:07 5:14 5:20 - 4:47 4:52 5:01 5:06 5:11 5:19 5:25 5:32 5:38 - 5:03 5:09 5:19 5:24 5:29 5:37 5:44 5:52 5:58 - - - 5:27 5:32 5:36 5:45 5:52 6:00 - - 5:19 5:25 5:35 5:40 5:44 5:53 6:00 6:09 - - - - 5:44 5:49 5:53 6:02 6:11 6:20 - - 5:34 5:41 5:53 5:58 6:02 6:13 6:22 6:31 - - - - 5:59 6:04 6:09 6:20 6:29 6:38 -

Far Rockaway Branch Effective Saturday and Sunday, November 14-15 & 21-22, 2020 Only Travel on This Affected Valley Stream Weekend Only

Effective Saturday and Sunday, November 14-15 & 21-22, 2020 Only Special Timetable For explanation, see Saturday Sunday Saturday Sunday For explanation, see Monday Monday Monday "Reference Notes." Only Only Only Only "Reference Notes." Only Only Only AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM PM AM AM AM Westbound FAR ROCKAWAY ...... 12:50 12:50 T 1:43 T 1:43 ...... 4:59 ...... 5:43 ...... 6:50 ...... 7:50 ...... 8:50 ...... 9:50 ...... 10:50 ...... 11:50 ...... 12:50 ...... FAR ROCKAWAY 1:50 ...... 2:50 ...... 3:50 ...... 4:50 ...... 5:50 ...... 6:50 ...... 7:50 ...... 8:50 ...... 9:50 ...... 10:50 ...... 11:59 ...... 12:48 1:47 Inwood ...... 12:54 12:54 T 1:47 T 1:47 ...... 5:03 ...... 5:48 ...... 6:55 ...... 7:55 ...... 8:55 ...... 9:55 ...... 10:55 ...... 11:55 ...... 12:55 ...... Inwood 1:55 ...... 2:55 ...... 3:55 ...... 4:55 ...... 5:55 ...... 6:55 ...... 7:55 ...... 8:55 ...... 9:55 ...... 10:55 ...... 12:05 ...... 12:52 1:50 Lawrence ...... 12:56 12:56 T 1:49 T 1:49 ...... 5:06 ...... 5:50 ...... 6:57 ...... 7:57 ...... 8:57 ...... 9:57 ...... 10:57 ...... 11:57 ...... 12:57 ...... Lawrence 1:57 ...... 2:57 ...... 3:57 ...... 4:57 ...... 5:57 ...... 6:57 ...... 7:57 ...... 8:57 ...... 9:57 ...... 10:57 ...... 12:08 ...... 12:54 1:53 Cedarhurst ...... 12:59 12:59 T 1:52 T 1:52 ..... -

Residents Talk, and NYCHA Listens Message from Chair and CEO Shola Olatoye

First-Class U.S. Postage Paid New York, NY Permit No. 4119 NYCHA Vol. 44 No. 4 www.nyc.gov/nycha May 2014 Message from Chair and CEO Shola Olatoye On May 5, Mayor Bill de Blasio unveiled NYCHA will develop a preservation and development plan that will be “Housing New York,” a plan to invest thoughtful and transparent. Starting from the ground up, we will listen to $41 billion to build or preserve 200,000 residents, using your input to create our approach and putting your needs affordable apartments across all five at the forefront of every decision. In partnership with you and a variety boroughs over the next 10 years. This of City agencies, elected officials, and community leaders and partners, ambitious plan is the largest ever in our we will ensure the success of “Housing New York.” Journanation’s history. It will provide housing The Mayor’s plan involves bothl preserving and developing housing. for at least a half million New Yorkers, For NYCHA, that means creating a thoughtful, practical approach which is more than the entire population which makes the best use of our resources and connects NYCHA to its of Atlanta. To help accomplish its very surrounding communities. Our efforts will support our mission to better important goal, 13 City agencies and more than 200 stakeholders – including maintain your homes. We also will focus on supporting the unique and NYCHA, affordable housing advocates, and elected officials – contributed growing needs of seniors. I know that our collaboration will guarantee to the plan’s development. “Housing New York” outlines more than 50 the long-term success, health, and vitality of our neighborhoods. -

Panews 2-01-07 V9

PA NEWS Published weekly for Port Authority and PATH employees February 1, 2007/Volume 6/Number 4 Business Briefs The e-Learning Institute Ship-to Rail Container Volumes Soar in ‘06 Takes ‘Show’ on the Road ExpressRail, the Port Authority’s ship-to- “The pur- rail terminals in New Jersey reached a new pose of the high in 2006 – handling a record 338,828 sessions is to cargo containers, 11.8 percent more than Photos: Gertrude Gilligan 2005. In the past seven years, the number show how the of containers transported by rail from the features and Port of New York and New Jersey has functions avail- grown by 113 percent. able on the The total volume now handled by Web site are ExpressRail will remove more than half a used, to Steve Carr and Dawn million truck trips annually from state and At an e-Learning launch demonstration at Lawrence demonstrate local roads, providing a substantial environ- 225 Park Avenue South on January 24 are receive feed- e-Learning’s capabili- mental benefit for the region. (from left) HRD’s Sylvia Shepherd, Wilma back, and ties and benefits. The dramatic increase in ExpressRail Baker, Steve Jones, Terence Joyce, and answer ques- activity came during a year when container Kayesandra Crozier. tions,” said Human Resources Acting volumes were up substantially. The port Director Rosetta Jannotto. set a new record during the first six ll aboard – sign up for months of 2006, surpassing 1.7 million a demonstration of the “Understanding the offerings and loaded 20-foot equivalent units handled A e-Learning Institute while tools of the Web site will enhance during the period for the first time. -

2010 Long Island Rail Road Service Reductions Includes Changes To

2010 Long Island Rail Road Service Reductions Includes Changes to Commuter Rail Service REVISED 2010 Long Island Rail Road Service Reductions Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... Page 1 Profile of Elements .................................................................................................... Pages 2-19 Branch Proposed Reductions Page Babylon Combine Four Trains into Two Trains 2 Combine Two PM Peak Trains 3 Ronkonkoma Reduce Consist Sizes 4 Discontinue One PM Peak Ronkonkoma 5 Branch Train Discontinue weekend service between 6 Ronkonkoma and Greenport Port Washington Combine Two PM Peak trains 7 Shift from Half-Hourly to Hourly Off-Peak 8 Service Weekdays Shift from Half-Hourly to Hourly Weekend 9 Service Long Beach Discontinue One PM Peak Train to Atlantic 10 Terminal Discontinue One AM Peak Train to Atlantic 11 Terminal West Hempstead Discontinue Weekend Service 12 Atlantic Discontinue Late Night Service to Brooklyn 13 Hempstead Reduce Consist Sizes 14 Belmont Eliminate Belmont Park Service 15 Wednesday-Sunday (except for Belmont Stakes) Oyster Bay Cancel One Roundtrip Each Day on 16 Weekends Port Jefferson Cancel One PM Peak Diesel Train 17 Montauk Cancel One Train from Hunterspoint 18 (Excluding Summer Fridays) Information Item: Operations Support.......................................................................... Page 19 System Map .................................................................................................................... -

FY 2022 EXECUTIVE BUDGET CITYWIDE SAVINGS PROGRAM—5 YEAR VALUE (City $ in 000’S)

The City of New York Executive Budget Fiscal Year 2022 Bill de Blasio, Mayor Mayor's Office of Management and Budget Jacques Jiha, Ph.D., Director Message of the Mayor The City of New York Executive Budget Fiscal Year 2022 Bill de Blasio, Mayor Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget Jacques Jiha, Ph.D., Director April 26, 2021 Message of the Mayor Contents BUDGET AND FINANCIAL PLAN SUMMARY Budget and Financial Plan Overview .......................................................................... 3 State and Federal Agenda ........................................................................................................... 4 Sandy Recovery .......................................................................................................................... 6 Contract Budget .......................................................................................................................... 9 Community Board Participation in the Budget Process ............................................................ 10 Economic Outlook .................................................................................................. 11 Tax Revenue .......................................................................................................... 27 Miscellaneous Receipts ............................................................................................ 52 Capital Budget ........................................................................................................ 58 Financing Program .................................................................................................