Appendix B Data Presentation the Presentation of Data Includes 634 Tobacco-Related Citations Collected from 566 Articles, Tran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electronic (E-) Cigarettes and Secondhand Aerosol

Defending your right to breathe smokefree air since 1976 Electronic (e-) Cigarettes and Secondhand Aerosol “If you are around somebody who is using e-cigarettes, you are breathing an aerosol of exhaled nicotine, ultra-fine particles, volatile organic compounds, and other toxins,” Dr. Stanton Glantz, Director for the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California, San Francisco. Current Legislative Landscape As of January 2, 2014, 108 municipalities and three states include e-cigarettes as products that are prohibited from use in smokefree environments. Constituents of Secondhand Aerosol E-cigarettes do not just emit “harmless water vapor.” Secondhand e-cigarette aerosol (incorrectly called vapor by the industry) contains nicotine, ultrafine particles and low levels of toxins that are known to cause cancer. E-cigarette aerosol is made up of a high concentration of ultrafine particles, and the particle concentration is higher than in conventional tobacco cigarette smoke.1 Exposure to fine and ultrafine particles may exacerbate respiratory ailments like asthma, and constrict arteries which could trigger a heart attack.2 At least 10 chemicals identified in e-cigarette aerosol are on California’s Proposition 65 list of carcinogens and reproductive toxins, also known as the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986. The compounds that have already been identified in mainstream (MS) or secondhand (SS) e-cigarette aerosol include: Acetaldehyde (MS), Benzene (SS), Cadmium (MS), Formaldehyde (MS,SS), Isoprene (SS), Lead (MS), Nickel (MS), Nicotine (MS, SS), N-Nitrosonornicotine (MS, SS), Toluene (MS, SS).3,4 E-cigarettes contain and emit propylene glycol, a chemical that is used as a base in e- cigarette solution and is one of the primary components in the aerosol emitted by e-cigarettes. -

Download Full Journal (PDF)

SAPIR A JOURNAL OF JEWISH CONVERSATIONS THE ISSUE ON POWER ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER RUTH CALDERON · MONA CHAREN MARK DUBOWITZ · DORE GOLD FELICIA HERMAN · BENNY MORRIS MICHAEL OREN · ANSHEL PFEFFER THANE ROSENBAUM · JONATHAN D. SARNA MEIR SOLOVEICHIK · BRET STEPHENS JEFF SWARTZ · RUTH R. WISSE Volume Two Summer 2021 And they saw the God of Israel: Under His feet there was the likeness of a pavement of sapphire, like the very sky for purity. — Exodus 24: 10 SAPIR Bret Stephens EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Mark Charendoff PUBLISHER Ariella Saperstein ASSO CIATE PUBLISHER Felicia Herman MANAGING EDITOR Katherine Messenger DESIGNER & ILLUSTRATOR Sapir, a Journal of Jewish Conversations. ISSN 2767-1712. 2021, Volume 2. Published by Maimonides Fund. Copyright ©2021 by Maimonides Fund. No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of Maimonides Fund. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. WWW.SAPIRJOURNAL.ORG WWW.MAIMONIDESFUND.ORG CONTENTS 6 Publisher’s Note | Mark Charendoff 90 MICHAEL OREN Trial and Triage in Washington 8 BRET STEPHENS The Necessity of Jewish Power 98 MONA CHAREN Between Hostile and Crazy: Jews and the Two Parties Power in Jewish Text & History 106 MARK DUBOWITZ How to Use Antisemitism Against Antisemites 20 RUTH R. WISSE The Allure of Powerlessness Power in Culture & Philanthropy 34 RUTH CALDERON King David and the Messiness of Power 116 JEFF SWARTZ Philanthropy Is Not Enough 46 RABBI MEIR Y. SOLOVEICHIK The Power of the Mob in an Unforgiving Age 124 ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER Power and Ethics in Jewish Philanthropy 56 ANSHEL PFEFFER The Use and Abuse of Jewish Power 134 JONATHAN D. -

What Inflamed the Iraq War?

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Fellowship Paper, University of Oxford What Inflamed The Iraq War? The Perspectives of American Cartoonists By Rania M.R. Saleh Hilary Term 2008 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my deepest appreciation to the Heikal Foundation for Arab Journalism, particularly to its founder, Mr. Mohamed Hassanein Heikal. His support and encouragement made this study come true. Also, special thanks go to Hani Shukrallah, executive director, and Nora Koloyan, for their time and patience. I would like also to give my sincere thanks to Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, particularly to its director Dr Sarmila Bose. My warm gratitude goes to Trevor Mostyn, senior advisor, for his time and for his generous help and encouragement, and to Reuter's administrators, Kate and Tori. Special acknowledgement goes to my academic supervisor, Dr. Eduardo Posada Carbo for his general guidance and helpful suggestions and to my specialist supervisor, Dr. Walter Armbrust, for his valuable advice and information. I would like also to thank Professor Avi Shlaim, for his articles on the Middle East and for his concern. Special thanks go to the staff members of the Middle East Center for hosting our (Heikal fellows) final presentation and for their fruitful feedback. My sincere appreciation and gratitude go to my mother for her continuous support, understanding and encouragement, and to all my friends, particularly, Amina Zaghloul and Amr Okasha for telling me about this fellowship program and for their support. Many thanks are to John Kelley for sharing with me information and thoughts on American newspapers with more focus on the Washington Post . -

U.S. Role in the World: Background and Issues for Congress

U.S. Role in the World: Background and Issues for Congress Ronald O'Rourke Specialist in Naval Affairs Michael Moodie Assistant Director and Senior Specialist in Foreign Affairs, Defense and Trade Updated February 24, 2020 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44891 U.S. Role in the World: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The U.S. role in the world refers to the overall character, purpose, or direction of U.S. participation in international affairs and the country’s overall relationship to the rest of the world. The U.S. role in the world can be viewed as establishing the overall context or framework for U.S. policymakers for developing, implementing, and measuring the success of U.S. policies and actions on specific international issues, and for foreign countries or other observers for interpreting and understanding U.S. actions on the world stage. While descriptions of the U.S. role in the world since the end of World War II vary in their specifics, it can be described in general terms as consisting of four key elements: global leadership; defense and promotion of the liberal international order; defense and promotion of freedom, democracy, and human rights; and prevention of the emergence of regional hegemons in Eurasia. The issue for Congress is whether the U.S. role in the world is changing, and if so, what implications this might have for the United States and the world. A change in the U.S. role could have significant and even profound effects on U.S. security, freedom, and prosperity. It could significantly affect U.S. -

Tobacco Reborn: the Rise of E-Cigarettes and Regulatory Approaches

LCB_25_3_Article_3_Aaron (Do Not Delete) 8/6/2021 9:26 AM TOBACCO REBORN: THE RISE OF E-CIGARETTES AND REGULATORY APPROACHES by Dr. Daniel G. Aaron* This Article examines e-cigarettes, FDA-regulated products which heat nico- tine-containing fluid into an aerosol to be breathed into the lungs. Recent data show that e-cigarettes are used by about one-fifth of U.S. high school students. Given that we have, in the Surgeon General’s words, reached an epidemic of youth e-cigarette use, it is worth asking how a product within FDA jurisdic- tion became a serious threat to 3.6 million youth. This Article reviews the law surrounding e-cigarettes and the history of FDA’s attempts to regulate them. Administrative law doctrines instruct us that in- creased presidential control will rein in misbehaving agencies by allowing the people to vote out a president who improperly directs the administrative state. However, e-cigarettes present a potent counterexample. On multiple occasions, presidential control over FDA stymied essential tobacco regulations by increas- ing the influence of the tobacco industry over expert agency policymaking. Yet children harmed by these tobacco policies have no right to vote and little po- litical clout with which to advocate for their interests. Ultimately, the emerg- ing approach to regulating e-cigarettes stands in opposition to a looming his- torical context and a boiling epidemic of nicotine addiction. By painting the context of e-cigarettes in lush detail, drawing from history, law, medicine, and public health, this Article charts a path forward for e-cigarettes and other ad- dicting products. -

She Said What? Interviews with Women Newspaper Columnists

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Women's Studies Gender and Sexuality Studies 4-7-1993 She Said What? Interviews with Women Newspaper Columnists Maria Braden University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Braden, Maria, "She Said What? Interviews with Women Newspaper Columnists" (1993). Women's Studies. 2. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_womens_studies/2 SHE SAID WHAT? This page intentionally left blank SHE SAID WHAT? Interviews with Women Newspaper Columnists MARIA BRADEN THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright © 1993 by Maria Braden Published by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2009 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-8131-9332-8 (pbk: acid-free paper) This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

Open PDF File, 8.71 MB, for February 01, 2017 Appendix In

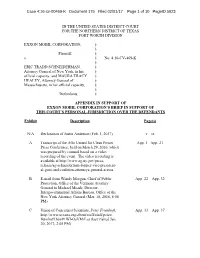

Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 1 of 10 PageID 5923 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS FORT WORTH DIVISION EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION, § § Plaintiff, § v. § No. 4:16-CV-469-K § ERIC TRADD SCHNEIDERMAN, § Attorney General of New York, in his § official capacity, and MAURA TRACY § HEALEY, Attorney General of § Massachusetts, in her official capacity, § § Defendants. § APPENDIX IN SUPPORT OF EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION’S BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF THIS COURT’S PERSONAL JURISDICTION OVER THE DEFENDANTS Exhibit Description Page(s) N/A Declaration of Justin Anderson (Feb. 1, 2017) v – ix A Transcript of the AGs United for Clean Power App. 1 –App. 21 Press Conference, held on March 29, 2016, which was prepared by counsel based on a video recording of the event. The video recording is available at http://www.ag.ny.gov/press- release/ag-schneiderman-former-vice-president- al-gore-and-coalition-attorneys-general-across B E-mail from Wendy Morgan, Chief of Public App. 22 – App. 32 Protection, Office of the Vermont Attorney General to Michael Meade, Director, Intergovernmental Affairs Bureau, Office of the New York Attorney General (Mar. 18, 2016, 6:06 PM) C Union of Concerned Scientists, Peter Frumhoff, App. 33 – App. 37 http://www.ucsusa.org/about/staff/staff/peter- frumhoff.html#.WI-OaVMrLcs (last visited Jan. 20, 2017, 2:05 PM) Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 2 of 10 PageID 5924 Exhibit Description Page(s) D Union of Concerned Scientists, Smoke, Mirrors & App. -

The Fear Profiteers

THE FEAR PROFITEERS: Do ‘Socially Responsible’ Businesses Sow Health Scares to Reap Monetary Rewards? Edited by Bonner Cohen, Ph.D. John Carlisle Michael Fumento Michael Gough, Ph.D. Henry Miller, M.D. Steven Milloy Kenneth Smith Elizabeth Whelan, Sc.D., M.P.H. Hundreds of thousands of deaths a year from smoking is old hat, but possible death by toxic waste, now that’s exciting. The problem is, such presentations distort the ability of viewers to engage in accurate risk assessment. The average viewer who watches story after story on the latest alleged environmental terror can hardly be blamed for coming to the conclusion that cigarettes are a small problem compared with the hazards of parts per quadrillion of dioxin in the air, or for concluding that the drinking of alcohol, a known cause of birth weight and cancer, is a small problem compared with the possibility of eating quantities of Alar almost too small to measure. This in turn results in pressure on the bureaucrats and politicians to wage war against tiny or nonexistent threats. The “war” gets more coverage as these politicians and bureaucrats thunder that the planet could not possibly survive without their intervention, and the vicious cycle goes on. ––Michael Fumento, Science Under Siege CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................... i-iii PREFACE.................................................................................................................I-III ACCIDENTALLY POISONOUS APPLES: Does Everything Cause -

University of California San Francisco

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN FRANCISCO BERKELEY • DAVIS • IRVINE • LOS ANGELES • MERCED • RIVERSIDE • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO SANTA BARBARA • SANTA CRUZ STANTON A. GLANTZ, PhD 530 Parnassus Suite 366 Professor of Medicine (Cardiology) San Francisco, CA 94143-1390 Truth Initiative Distinguished Professor of Tobacco Control Phone: (415) 476-3893 Director, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education Fax: (415) 514-9345 [email protected] December 20, 2017 Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee c/o Caryn Cohen Office of Science Center for Tobacco Products Food and Drug Administration Document Control Center Bldg. 71, Rm. G335 10903 New Hampshire Ave. Silver Spring, MD 20993–0002 [email protected] Re: 82 FR 27487, Docket no. FDA-2017-D-3001-3002 for Modified Risk Tobacco Product Applications: Applications for IQOS System With Marlboro Heatsticks, IQOS System With Marlboro Smooth Menthol Heatsticks, and IQOS System With Marlboro Fresh Menthol Heatsticks Submitted by Philip Morris Products S.A.; Availability Dear Committee Members: We are submitting the 10 public comments that we have submitted to the above-referenced docket on Philip Morris’s modified risk tobacco product applications (MRTPA) for IQOS. It is barely a month before the meeting and the docket on IQOS has not even closed. As someone who has served and does serve on committees similar to TPSAC, I do not see how the schedule that the FDA has established for TPSAC’s consideration of this application can permit a responsible assessment of the applications and associated public comments. I sincerely hope that you will not be pressed to make any recommendations on the IQOS applications until the applications have been finalized, the public has had a reasonable time to assess the applications, and TPSAC has had a reasonable time to digest both the completed applications and the public comments before making any recommendation to the FDA. -

Ronald Reagan in Memoriam

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Features Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies 6-6-2004 Ronald Reagan in Memoriam Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/features Recommended Citation "Ronald Reagan in Memoriam" (2004). Features. Paper 91. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/features/91 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Features by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ronald Reagan In Memoriam - Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies - Grand Valley... Page 1 of 32 Ronald Reagan In Memoriam Ronald Reagan In Memoriam Our 40th president's life, career, death, and funeral are recalled in this Hauenstein Center focus. Detroit Free Press A Milliken Republican was driven to honor Reagan Column By Dawson Bell - Detroit Free Press (June 14, 2004) "The Michigan Republican Party Jerry Roe served as executive director in the 1970s wasn't exactly ground zero in the Reagan Revolution." FULL TEXT One thing's for sure, he kept to the script Column By Rochelle Riley - Detroit Free Press (June 11, 2004) "He took on his greatest acting role, as president of the United States, in a sweeping epic drama about one national superpower making itself stronger while growing tired of a second nipping at its heels with waning threats of nuclear annihilation." FULL TEXT Media do not tell the truth about Reagan Column By Leonard Pitts Jr. - Detroit Free Press (June 11, 2004) "Philadelphia, a speck of a town north and east of Jackson, is infamous as the place three young civil rights workers were murdered in 1964 for registering black people to vote. -

Behind Janus: Documents Reveal Decade-Long Plot to Kill Public-Sector Unions

Behind Janus: Documents Reveal Decade-Long Plot to Kill Public-Sector Unions The Supreme Court case Janus v. AFSCME is poised to decimate public-sector unions—and it’s been made possible by a network of right-wing billionaires, think tanks and corporations. MARY BOTTARI FEBRUARY 22, 2018 | MARCH ISSUE In These Times THE ROMAN GOD JANUS WAS KNOWN FOR HAVING TWO FACES. It is a fitting name for the U.S. Supreme Court case scheduled for oral arguments February 26, Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, Council 31, that could deal a devastating blow to public-sector unions and workers nationwide. In the past decade, a small group of people working for deep-pocketed corporate interests, conservative think tanks and right-wing foundations have bankrolled a series of lawsuits to end what they call “forced unionization.” They say they fight in the name of “free speech,” “worker rights” and “workplace freedom.” In briefs before the court, they present their public face: carefully selected and appealing plaintiffs like Illinois child-support worker Mark Janus and California schoolteacher Rebecca Friedrichs. The language they use is relentlessly pro-worker. Behind closed doors, a different face is revealed. Those same people cheer “defunding” and “bankrupting” unions to deal a “mortal blow” to progressive politics in America. A key director of this charade is the State Policy Network (SPN), whose game plan is revealed in a union-busting toolkit uncovered by the Center for Media and Democracy. The first rule of the national network of right-wing think tanks that are pushing to dismantle unions? “Rule #1: Be pro-worker, not anti-union. -

Association Are You Guilty? Ask the FBI

BEST POLITICAL DOCS • KOSHER GETS ETHICAL JANUARY 2011 Chicago's other community organizer How to manufacture a disease TERRORIST BY ASSOCIATION Are you guilty? Ask the FBI. BY JEREMY GANTZ PLUS Chris Lehmann takes down the Babbitt of the Bobos, David Brooks letters syrup does not appear isn’t subsidized because the to push the boundaries and to be a measureable manufacturer itself may not struggle to earn recognition contributor to mercury be directly on the dole. The in a marketplace dominated in foods. large agribusinesses that by four or five major labels Also, it is important to grow corn reap not only worldwide. note that manufacturers grain, but lavish government The article’s dramatic of corn sweeteners do not handouts through what I headline reflects the au- receive government support called “skewed government thor’s out-of-date viewpoint. payments. Our industry buys policies.” That means that tax Nostalgia blinds Lears to corn on the open market at dollars allow HFCS manu- the present. It’s a viewpoint the prevailing market price. facturers to take advantage clearly evident when she Audrae Erickson, President of artificially cheap corn writes: “Those of us avid Corn Refiners Association prices to produce artificially listeners who came of age Washington, D.C. cheap HFCS. in the 1990s and earlier re- member how much effort it The mercurial TERRY J. ALLEN Exorcising ‘90s nostalgia science of syrup took to learn about obscure RESPONDS With all due respect, Rachel bands and track down their The American public can rest You have confirmed in an Lears in “The End of Indie?,” recordings.” assured that high fructose email to ITT that Stopford’s (December 2010) misses the Indie music isn’t dead by a corn syrup is safe (“Let Them study was not independent: point.