UNDERSTANDING POWER the INDISPENSABLE CHOMSKY Edited by Peter R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.3 Holocaust Denial

nm u Ottawa L'Universite eanadienne Canada's university mn FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES 1=^1 FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES L'Universite eanadienne Canada's university Johny-Angel Butera AUTEUR DE LA THESE / AUTHOR OF THESIS M.A. (Criminology) GRADE/DEGREE Department of Criminology FACULTE, ECOLE, DEPARTEMENT / FACULTY, SCHOOL, DEPARTMENT Genocide Denial on the Internet: The Cases of Armenia and Rwanda TITRE DE LA THESE / TITLE OF THESIS Maritza Felices-Luna DIRECTEUR (DIRECTRICE) DE LA THESE / THESIS SUPERVISOR CO-DIRECTEUR (CO-DIRECTRICE) DE LA THESE /THESIS CO-SUPERVISOR Daniel dos Santos Valerie Steeves Gary W. Slater Le Doyen de la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctorales / Dean of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies GENOCIDE DENIAL ON THE INTERNET: THE CASES OF ARMENIA AND RWANDA Johny-Angel Butera Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the MA degree in Criminology Department of Criminology Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Johny-Angel Butera, Ottawa, Canada, 2010 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r&terence ISBN: 978-0-494-73798-9 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-73798-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license -

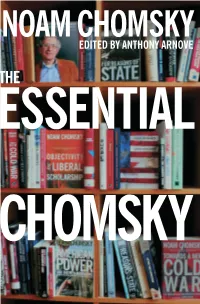

Essential Chomsky

CURRENT AFFAIRS $19.95 U.S. CHOMSKY IS ONE OF A SMALL BAND OF NOAM INDIVIDUALS FIGHTING A WHOLE INDUSTRY. AND CHOMSKY THAT MAKES HIM NOT ONLY BRILLIANT, BUT HEROIC. NOAM CHOMSKY —ARUNDHATI ROY EDITED BY ANTHONY ARNOVE THEESSENTIAL C Noam Chomsky is one of the most significant Better than anyone else now writing, challengers of unjust power and delusions; Chomsky combines indignation with he goes against every assumption about insight, erudition with moral passion. American altruism and humanitarianism. That is a difficult achievement, —EDWARD W. SAID and an encouraging one. THE —IN THESE TIMES For nearly thirty years now, Noam Chomsky has parsed the main proposition One of the West’s most influential of American power—what they do is intellectuals in the cause of peace. aggression, what we do upholds freedom— —THE INDEPENDENT with encyclopedic attention to detail and an unflagging sense of outrage. Chomsky is a global phenomenon . —UTNE READER perhaps the most widely read voice on foreign policy on the planet. ESSENTIAL [Chomsky] continues to challenge our —THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW assumptions long after other critics have gone to bed. He has become the foremost Chomsky’s fierce talent proves once gadfly of our national conscience. more that human beings are not —CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT, condemned to become commodities. THE NEW YORK TIMES —EDUARDO GALEANO HO NE OF THE WORLD’S most prominent NOAM CHOMSKY is Institute Professor of lin- Opublic intellectuals, Noam Chomsky has, in guistics at MIT and the author of numerous more than fifty years of writing on politics, phi- books, including For Reasons of State, American losophy, and language, revolutionized modern Power and the New Mandarins, Understanding linguistics and established himself as one of Power, The Chomsky-Foucault Debate: On Human the most original and wide-ranging political and Nature, On Language, Objectivity and Liberal social critics of our time. -

The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003

THE REGIME CHANGE CONSENSUS: IRAQ IN AMERICAN POLITICS, 1990-2003 Joseph Stieb A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Wayne Lee Michael Morgan Benjamin Waterhouse Daniel Bolger Hal Brands ©2019 Joseph David Stieb ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joseph David Stieb: The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003 (Under the direction of Wayne Lee) This study examines the containment policy that the United States and its allies imposed on Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War and argues for a new understanding of why the United States invaded Iraq in 2003. At the core of this story is a political puzzle: Why did a largely successful policy that mostly stripped Iraq of its unconventional weapons lose support in American politics to the point that the policy itself became less effective? I argue that, within intellectual and policymaking circles, a claim steadily emerged that the only solution to the Iraqi threat was regime change and democratization. While this “regime change consensus” was not part of the original containment policy, a cohort of intellectuals and policymakers assembled political support for the idea that Saddam’s personality and the totalitarian nature of the Baathist regime made Iraq uniquely immune to “management” strategies like containment. The entrenchment of this consensus before 9/11 helps explain why so many politicians, policymakers, and intellectuals rejected containment after 9/11 and embraced regime change and invasion. -

According to Wikipedia 2011 with Some Addictions

American MilitMilitaryary Historians AAA-A---FFFF According to Wikipedia 2011 with some addictions Society for Military History From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Society for Military History is an United States -based international organization of scholars who research, write and teach military history of all time periods and places. It includes Naval history , air power history and studies of technology, ideas, and homefronts. It publishes the quarterly refereed journal titled The Journal of Military History . An annual meeting is held every year. Recent meetings have been held in Frederick, Maryland, from April 19-22, 2007; Ogden, Utah, from April 17- 19, 2008; Murfreesboro, Tennessee 2-5 April 2009 and Lexington, Virginia 20-23 May 2010. The society was established in 1933 as the American Military History Foundation, renamed in 1939 the American Military Institute, and renamed again in 1990 as the Society for Military History. It has over 2,300 members including many prominent scholars, soldiers, and citizens interested in military history. [citation needed ] Membership is open to anyone and includes a subscription to the journal. Officers Officers (2009-2010) are: • President Dr. Brian M. Linn • Vice President Dr. Joseph T. Glatthaar • Executive Director Dr. Robert H. Berlin • Treasurer Dr. Graham A. Cosmas • Journal Editor Dr. Bruce Vandervort • Journal Managing Editors James R. Arnold and Roberta Wiener • Recording Secretary & Photographer Thomas Morgan • Webmaster & Newsletter Editor Dr. Kurt Hackemer • Archivist Paul A. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

Brigitte Bailer-Galanda “Revisionism”1 in Germany and Austria: the Evolution of a Doctrine

www.doew.at Brigitte Bailer-Galanda “Revisionism”1 in Germany and Austria: The Evolution of a Doctrine Published in: Hermann Kurthen/Rainer Erb/Werner Bergmann (ed.), Anti-Sem- itism and Xenophobia in Germany after Unification, New York–Oxford 1997 Development of “revisionism” since 1945 Most people understand so called „revisionism“ as just another word for the movement of holocaust denial (Benz 1994; Lipstadt 1993; Shapiro 1990). Therefore it was suggested lately to use the word „negationism“ instead. How- ever in the author‘s point of view „revisionism“ covers some more topics than just the denying of the National Socialist mass murders. Especially in Germany and Austria there are some more points of National Socialist politics some people have tried to minimize or apologize since 1945, e. g. the responsibility for World War II, the attack on the Soviet Union in 1941 (quite a modern topic), (the discussion) about the number of the victims of the holocaust a. s. o.. In the seventies the late historian Martin Broszat already called that movement „run- ning amok against reality“ (Broszat 1976). These pseudo-historical writers, many of them just right wing extremist publishers or people who quite rapidly turned to right wing extremists, really try to prove that history has not taken place, just as if they were able to make events undone by denying them. A conception of “negationism” (Auerbach 1993a; Fromm and Kernbach 1994, p. 9; Landesamt für Verfassungsschutz 1994) or “holocaust denial” (Lipstadt 1993, p. 20) would neglect the additional components of “revision- ism”, which are logically connected with the denying of the holocaust, this being the extreme variant. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Why Does Israel Support the Kurdish Independence? Publish Date: 01/10/2017

Artical Name : Isolating Threats Artical Subject : Why does Israel Support the Kurdish Independence? Publish Date: 01/10/2017 Auther Name: Mona Soliman Subject : 9/30/2021 3:40:09 PM 1 / 2 The statement of the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, issued supporting the independence of the Kurdistan region, revealed that the Israeli position runs contrary to most regional and international powers opposing the referendum. Tel Aviv seeks to use Iraqi Kurdistan to pressure Iran, incite the Kurds in Iran, Syria and Turkey to secede and create a geographical buffer zone against Iran. The Israeli stance is inseparable from the history of close cooperation between Israel and Iraqi Kurds.Secession¶s SponsorshipThere are several indicators, which demonstrate Israel¶s support for the independence of Iraqi Kurdistan: 1. Official statements: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu voiced, more than once, his support for the secession of Iraqi Kurdistan from Iraq and the creation of a Kurdish State in the North of the country. In a speech in 2014 at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv, Netanyahu called the Kurds ³a nation of fighters [who] have proved political commitment and are worthy of independence´a statement that angered Baghdad at that time. He also reaffirmed his stance during a meeting with a delegation from the US Congress, on August 13, 2017, stressing that he backs Iraqi Kurdistan¶s independence from Iraq, because the Kurdish people are brave and loyal to the West, as well as they share the same values with Israel. On the other hand, the Kurds cheered those remarks by raising the Israeli flag during their demonstrations in favor of independence in Erbil and several European capitals, where there are Kurdish communities such as Paris, Brussels and Berlin.In addition, several Israeli politicians declared their support for the independence of Iraqi Kurdistan from Iraq. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 052 058 SE 012 062 AUTHOR Kohn, Raymond F. Environmental Education, the Last Measure of Man. an Anthology Of

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 052 058 SE 012 062 AUTHOR Kohn, Raymond F. TITLE Environmental Education, The Last Measure of Man. An Anthology of Papers for the Consideration of the 14th and 15th Conference of the U.S. National Commission for UNESCO. INSTITUTION National Commission for UNESCO (Dept. of State), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 199p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Anthologies, *Ecology, *Environment, EnVironmental Education, Environmental Influences, *Essays, *Human Engineering, Interaction, Pollution IDENTIFIERS Unesco ABSTRACT An anthology of papers for consideration by delegates to the 14th and 15th conferences of the United States National Commission for UNESCO are presented in this book. As a wide-ranging collection of ideas, it is intended to serve as background materials for the conference theme - our responsibility for preserving and defending a human environment that permits the full growth of man, physical, cultural, and social. Thirty-four essays are contributed by prominent authors, educators, historians, ecologists, biologists, anthropologists, architects, editors, and others. Subjects deal with the many facets of ecology and the environment; causes, effects, and interactions with man which have led to the crises of today. They look at what is happening to man's "inside environment" in contrast to the physical or outside environment as it pertains to pollution of the air, water, and land. For the common good of preserving the only means for man's survival, the need for world cooperation and understanding is emphatically expressed. (BL) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. -

Germar Rudolf's Bungled

Bungled: “DENYING THE HOLOCAUST” Bungled: “Denying the Holocaust” How Deborah Lipstadt Botched Her Attempt to Demonstrate the Growing Assault on Truth and Memory Germar Rudolf !"# !$ %&' Germar Rudolf : Bungled: “Denying the Holocaust”: How Deborah Lipstadt Botched Her Attempt to Demonstrate the Growing Assault on Truth and Memory Uckfield, East Sussex: CASTLE HILL PUBLISHERS PO Box 243, Uckfield, TN22 9AW, UK 2nd edition, April 2017 ISBN10: 1-59148-177-5 (print edition) ISBN13: 978-1-59148-177-5 (print edition) Published by CASTLE HILL PUBLISHERS Manufactured worldwide © 2017 by Germar Rudolf Set in Garamond GERMAR RUDOLF· BUNGLED: “DENYING THE HOLOCAUST” 5 Table of Contents 1.Introduction ................................................................................... 7 2.Science and Pseudo-Science ...................................................... 15 2.1.What Is Science? ........................................................................... 15 2.2.What Is Pseudo-Science? ............................................................. 26 3.Motivations and ad Hominem Attacks ....................................... 27 3.1.Revisionist Motives According to Lipstadt ............................... 27 3.2.Revisionist Methods According to Lipstadt .............................. 40 3.3.Deborah Lipstadt’s Motives and Agenda .................................. 50 4.Revisionist Personalities ............................................................. 67 4.1.Maurice Bardèche ........................................................................ -

Israeli Involvement in Central America Nothing New Deborah Tyroler

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiCen Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 2-4-1987 Israeli Involvement In Central America Nothing New Deborah Tyroler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/noticen Recommended Citation Tyroler, Deborah. "Israeli Involvement In Central America Nothing New." (1987). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/noticen/395 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiCen by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 077181 ISSN: 1089-1560 Israeli Involvement In Central America Nothing New by Deborah Tyroler Category/Department: General Published: Wednesday, February 4, 1987 * For the majority of Americans Irangate provided the first hint of Israeli military involvement with the contras. However, Israel's support of reactionary governments and other groups in Central America is nothing new. That nation has provided arms to the military, advice and training to police forces, and sophisticated counter-insurgency techniques to Central American dictatorships for at least 30 years. Israel has not broadcast its role in Central America, nor has the mainstream US media considered Tel Aviv's actions in the region worthy of consistent coverage. Torn between gaining the good will of the American right-wing, on the one hand, and with offending liberals, on the other, Israel has opted for a low profile. In part, Tel Aviv's reaction to the Iran-contragate revelations stems from fear that the full story of Israel's role in Central America will become widely known.