Thesis US Cuba.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

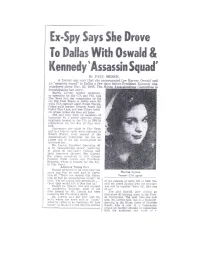

Ex-Spy Says She Drove to Dallas with Oswald & Kennedy 'Assassin

Ex-Spy Says She Drove To Dallas With Oswald & Kennedy 'Assassin Squad' By PAUL MESKIL A former spy says that she accompanied Lee Harvey Oswald and an "assassin squad" to Dallas a few days before President Kennedy was murdered there Nov. 22, 1963. The House Assassinations Committee is investigating her story. Marita Lorenz, former undercov- er operative for the CIA and FBI, told The News that her companions on the car trip from Miami to Dallas were Os. wald, CIA contract agent Frank Sturgis, Cuban exile leaders Orlando Bosch and Pedro Diaz Lanz, and two Cuban broth- ers whose names she does not know. She said they were all members of Operation 40, a secret guerrilla group originally formed by the CIA in 1960 in preparation for the Bay of Pigs inva- sion. Statements she made to The News and to a federal agent were reported to Robert Blakey, chief counsel of the Assassinations Committee. He has as- signed one of his top investigators to interview her. Ms. Lorenz described Operation 40 as an ''assassination squad" consisting of about 30 anti-Castro Cubans and their American advisers. She claimed the group conspired to kill Cuban Premier Fidel Castro and President Kennedy, whom it blamed for the Bay of Pigs fiasco. Admitted Taking Part Sturgis admitted in an interview two years ago that he took part in Opera- Maritza Lorenz tion 40. "There are reports that Opera- Farmer CIA agent tion 40 had an assassination squad." he said. "I'm not saying that personally ... In the summer or early fall of 1963. -

The Cuban American National Foundation and Its Role As an Ethnic Interest Group

The Cuban American National Foundation and Its Role as an Ethnic Interest Group Author: Margaret Katherine Henn Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/568 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2008 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Introduction Since the 1960s, Cuban Americans have made social, economic, and political progress far beyond that of most immigrant groups that have come to the United States in the past fifty years. I will argue that the Cuban American National Foundation (CANF) was very influential in helping the Cuban Americans achieve much of this progress. It is, however, important to note that Cubans had some distinct advantages from the beginning, in terms of wealth and education. These advantages helped this ethnic interest group to grow quickly and become powerful. Since its inception in the early 1980s, the CANF has continually been able to shape government policy on almost all issues related to Cuba. Until at least the end of the Cold War, the CANF and the Cuban American population presented a united front in that their main goal was to present a hard line towards Castro and defeat him; they sought any government assistance they could get to achieve this goal, from policy changes to funding for different dissident activities. In more recent years, Cubans have begun to differ in their opinions of the best policy towards Cuba. I will argue that this change along with other changes will decrease the effectiveness of the CANF. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

The 1970S: Pluralization, Radicalization, and Homeland

ch4.qxd 10/11/1999 10:10 AM Page 84 CHAPTER 4 The 1970s: Pluralization, Radicalization, and Homeland As hopes of returning to Cuba faded, Cuban exiles became more con- cerned with life in the United States. Exile-related struggles were put on the back burner as more immediate immigrant issues emerged, such as the search for better jobs, education, and housing. Class divisions sharpened, and advocacy groups seeking improved social services emerged, including, for example, the Cuban National Planning Council, a group of Miami social workers and businesspeople formed in the early 1970s. As an orga- nization that provided services to needy exiles, this group de‹ed the pre- vailing notion that all exiles had made it in the United States. Life in the United States created new needs and interests that could only be resolved, at least in part, by entering the domestic political arena. Although there had always been ideological diversity within the Cuban émigré community, it was not until the 1970s that the political spec- trum ‹nally began to re›ect this outwardly.1 Two sharply divided camps emerged: exile oriented (focused on overthrowing the Cuban revolution- ary government) and immigrant oriented (focused on improving life in the United States). Those groups that were not preoccupied with the Cuban revolution met with hostility from those that were. Exile leaders felt threat- ened by organized activities that could be interpreted as an abandonment of the exile cause. For example, in 1974 a group of Cuban exile researchers conducted an extensive needs assessment of Cubans in the United States and concluded that particular sectors, such as the elderly and newly arrived immigrants, were in need of special intervention.2 When their ‹ndings were publicized, they were accused of betraying the community because of their concern with immigrant problems rather than the over- throw of the revolution. -

AUGE Y CAÍDA DE REPORTEROS SIN FRONTERAS El Dossier Robert Ménard Jean-Guy Allard

AUGE Y CAÍDA DE REPORTEROS SIN FRONTERAS El dossier Robert Ménard Jean-Guy Allard Con la colaboración de Marie-Dominique Bertuccioli AUGE Y CAÍDA DE REPORTEROS SIN FRONTERAS El dossier Robert Ménard Jean-Guy Allard Ministerio del Poder Poder Popular para la Comunicación y la Información; Av. Universidad, Esq. El Chorro, Torre Ministerial, pisos 9 y 10. Caracas-Venezuela www.minci.gob.ve / [email protected] Soy autoritario. No sé discutir y me gusta decidir yo solo. ROBE R T MÉNA R D DIRECTORIO Ministro del Poder Popular para la Comunicación y la Información Andrés Izarra Viceministro de Gestión Comunicacional Mauricio Rodríguez Viceministro de Estrategia Comunicacional Freddy Fernández Directora General de Difusión y Publicidad Mayberth Graterol Director de Publicaciones “La democracia y los derechos Gabriel González Diseño y diagramación humanos nos interesan muy poco. Ingrid Rodríguez M. Estas palabras las utilizamos simplemente Edición Sylvia Sabogal para ocultar nuestros verdaderos motivos”. Corrección WAYNE SM ITH . José Daniel Cuevas Jefe de la Sección de Intereses Mayo, 2008. de los Estados Unidos en La Habana, de 1979 a 1982. Depósito Legal: lf87120083842153 Impreso en la República Bolivariana de Venezuela. A los cinco héroes cubanos Condenados por haber infiltrado grupos terroristas cubanoamericanos creados y protegidos por el Gobierno de Washington. I ¿Ménard, agente de la CIA? AUGE Y CAÍDA DE REPORTEROS SIN FRONTERAS: El dossier Robert Ménard ampañas de prensa, declaraciones en la radio y la televisión, anuncios a toda página en los grandes diarios parisinos, dis- Ctribución de volantes, Reporteros sin fronteras no escatima medios para convencer a la opinión pública francesa e internacional de que países en conflicto con Washington son “predadores de la libertad de expresión”. -

The United States' Janus-Faced Approach to Operation Condor: Implications for the Southern Cone in 1976

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2008 The United States' Janus-Faced Approach to Operation Condor: Implications for the Southern Cone in 1976 Emily R. Steffan University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Steffan, Emily R., "The United States' Janus-Faced Approach to Operation Condor: Implications for the Southern Cone in 1976" (2008). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1235 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emily Steffan The United States' Janus-Faced Approach To Operation Condor: Implications For The Southern Cone in 1976 Emily Steffan Honors Senior Project 5 May 2008 1 Martin Almada, a prominent educator and outspoken critic of the repressive regime of President Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay, was arrested at his home in 1974 by the Paraguayan secret police and disappeared for the next three years. He was charged with being a "terrorist" and a communist sympathizer and was brutally tortured and imprisoned in a concentration camp.l During one of his most brutal torture sessions, his torturers telephoned his 33-year-old wife and made her listen to her husband's agonizing screams. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

Jorge Mas Canosa Made His New Country Pay Attention

Jorge Mas Canosa made his new country pay attention BY ROBERT G. TORRICELLI @bobtorricelli SEPTEMBER 20, 2017 12:52 AM Meeting Jorge Mas Canosa was like walking into a hurricane. He was a force of nature driven by gusts of ambition and love that swirled around a calm eye of Latin charm. That storm entered my congressional office in the spring of 1986. The Cuban American National Foundation had achieved prominence with its calculated embrace of Ronald Reagan. Mastec, the Florida Corporation he founded, was feeding off the national thirst for technology. But, mostly, the deadly strife in Central America had Fidel Castro back in the news. We were an unlikely pair. A liberal suburban congressman, the product of the post- war American middle class, listened attentively to this Cuban émigré, who this year will have been dead for two decades. Revolution forced him from his homeland, and he was on a mission to destroy Castro’s regime. It would become one of the most important relationships of my life. WATCH VIDEO: Jorge Mas Canosa in action Castro occupied a special place for my generation. He was the animated figure on television. He factored into our parents’ decision to pile canned food, water, and radios in our basements. Before Vietnam, there was Castro interrupting the rhythm of American life with tirades and revolution. Canosa understood the moment. The network that he built in Congress was formidable and strengthened by Cuba’s meddling in Africa and Central America. The latent hostility of my generation was fuel in search of a match. -

The Bay of Pigs Invasion As the Us's

THE BAY OF PIGS INVASION AS THE US’S ‘PERFECT FAILURE’ FE LORRAINE REYES MONTCLAIR STATE UNIVERSITY Sixty years ago today, April 17, 1961, a CIA-operated group of Cuban exiles sought to overthrow the communist regime of Fidel Castro in what is known as the Bay of Pigs invasion. The planning for this overthrow culminated in 1960 when President Dwight Eisenhower ordered for the classified training of 1400 anti-Castro dissidents tasked with overthrowing the Prime Minister the following year. The Cold War had sparked tensions between Cuba and the United States. Cuba, which was strengthening its relations with communist Soviet Union, became a national security threat. The United States feared both the ideological spread of communism and a severed tie with Cuba, which the US remained tethered to for its own economic interest. Inevitably, the plans, fueled by fear and the preservation of national interests, were inherited by the Kennedy administration in January 1960. What John F. Kennedy did not anticipate was how the CIA’s invasion of Cuba’s southern beach would tarnish the world’s view of democracy for generations to come. Although the United States had intended to sever ties with Cuba (and, effectively, the Soviet base on its shores), the invasion, in turn, extended communist powers and protracted the downfall of the Soviet Union. The oversights in the CIA’s plans are why the Bay of Pigs became recognized as a catastrophic failure that emboldened the tension between the US and foreign powers and bookmarked the political relationship between the US, Cuba, and the Soviet Union. -

Diaspora and Deadlock, Miami and Havana: Coming to Terms with Dreams and Dogmas Francisco Valdes University of Miami School of Law, [email protected]

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 2003 Diaspora and Deadlock, Miami and Havana: Coming to Terms With Dreams and Dogmas Francisco Valdes University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Francisco Valdes, Diaspora and Deadlock, Miami and Havana: Coming to Terms With Dreams and Dogmas, 55 Fla.L.Rev. 283 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIASPORA AND DEADLOCK, MIAMI AND HAVANA: COMING TO TERMS WITH DREAMS AND DOGMAS Francisco Valdes* I. INTRODUCTION ............................. 283 A. Division and Corruption:Dueling Elites, the Battle of the Straits ...................................... 287 B. Arrogation and Class Distinctions: The Politics of Tyranny and Money ................................. 297 C. Global Circus, Domestic Division: Cubans as Sport and Spectacle ...................................... 300 D. Time and Imagination: Toward the Denied .............. 305 E. Broken Promisesand Bottom Lines: Human Rights, Cuban Rights ...................................... 310 F. Reconciliationand Reconstruction: Five LatCrit Exhortations ...................................... 313 II. CONCLUSION .......................................... 317 I. INTRODUCTION The low-key arrival of Elian Gonzalez in Miami on Thanksgiving Day 1999,1 and the custody-immigration controversy that then ensued shortly afterward,2 transfixed not only Miami and Havana but also the entire * Professor of Law and Co-Director, Center for Hispanic & Caribbean Legal Studies, University of Miami. -

''Diplomatic Assurances'' on Torture: a Case Study Of

‘‘DIPLOMATIC ASSURANCES’’ ON TORTURE: A CASE STUDY OF WHY SOME ARE ACCEPTED AND OTHERS REJECTED HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND OVERSIGHT OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 15, 2007 Serial No. 110–138 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–939PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS TOM LANTOS, California, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DAN BURTON, Indiana Samoa ELTON GALLEGLY, California DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey DANA ROHRABACHER, California BRAD SHERMAN, California DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois ROBERT WEXLER, Florida EDWARD R. ROYCE, California ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio BILL DELAHUNT, Massachusetts ROY BLUNT, Missouri GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado DIANE E. WATSON, California RON PAUL, Texas ADAM SMITH, Washington JEFF FLAKE, Arizona RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri MIKE PENCE, Indiana JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee JOE WILSON, South Carolina GENE GREEN, Texas JOHN BOOZMAN, Arkansas LYNN C. WOOLSEY, California J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas CONNIE MACK, Florida RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York MICHAEL T. -

Redalyc.Myths About Cuba

História: Debates e Tendências ISSN: 1517-2856 [email protected] Universidade de Passo Fundo Brasil Domínguez, Francisco Myths about Cuba História: Debates e Tendências, vol. 10, núm. 1, enero-junio, 2010, pp. 9-34 Universidade de Passo Fundo Passo Fundo, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=552456400004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Myths about Cuba Francisco Domínguez * Abstract His article aims at deconstructing Cuba is not perfect. Blocaded and sub- this fallacious though no less powerful jected to the unrelenting harassment mythology that has been constructed and aggression by the most powerful about Cuban reality, not an easy task military machine of the history of hu- that sometimes reminds us of Thomas manity for five decades cannot avoid Carlyle biographer of Oliver Cromwell, suffering from deficiencies, shortages, who said he “had to drag out the Lord distortions, inefficiencies and other di- Protector from under a mountain of fficulties. However, since literally 1959, dead dogs, a huge load of calumny.” the Cuban revolution has been subjec- All proportions guarded, it must have ted to a defamation campaign that has been much easier for Carlyle to remo- managed to embed a demonized de- ve the mountain of dead dogs from the piction of her reality in the brains of memory of Cromwell that to undo the millions of innocent consumers of mass infinite torrent of calumnies that falls media “information”.