She Said What? Interviews with Women Newspaper Columnists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bud Fisher—Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Winter 1979 Bud Fisher—Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists Ray Thompson Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the American Popular Culture Commons Recommended Citation Thompson, Ray. "Bud Fisher—Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists." The Courier 16.3 and 16.4 (1979): 23-36. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSN 0011-0418 ARCHIMEDES RUSSELL, 1840 - 1915 from Memorial History ofSyracuse, New York, From Its Settlement to the Present Time, by Dwight H. Bruce, Published in Syracuse, New York, by H.P. Smith, 1891. THE COURIER SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES Volume XVI, Numbers 3 and 4, Winter 1979 Table of Contents Winter 1979 Page Archimedes Russell and Nineteenth-Century Syracuse 3 by Evamaria Hardin Bud Fisher-Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists 23 by Ray Thompson News of the Library and Library Associates 37 Bud Fisher - Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists by Ray Thompson The George Arents Research Library for Special Collections at Syracuse University has an extensive collection of original drawings by American cartoonists. Among the most famous of these are Bud Fisher's "Mutt and Jeff." Harry Conway (Bud) Fisher had the distinction of producing the coun try's first successful daily comic strip. Comics had been appearing in the press of America ever since the introduction of Richard F. -

Download Full Journal (PDF)

SAPIR A JOURNAL OF JEWISH CONVERSATIONS THE ISSUE ON POWER ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER RUTH CALDERON · MONA CHAREN MARK DUBOWITZ · DORE GOLD FELICIA HERMAN · BENNY MORRIS MICHAEL OREN · ANSHEL PFEFFER THANE ROSENBAUM · JONATHAN D. SARNA MEIR SOLOVEICHIK · BRET STEPHENS JEFF SWARTZ · RUTH R. WISSE Volume Two Summer 2021 And they saw the God of Israel: Under His feet there was the likeness of a pavement of sapphire, like the very sky for purity. — Exodus 24: 10 SAPIR Bret Stephens EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Mark Charendoff PUBLISHER Ariella Saperstein ASSO CIATE PUBLISHER Felicia Herman MANAGING EDITOR Katherine Messenger DESIGNER & ILLUSTRATOR Sapir, a Journal of Jewish Conversations. ISSN 2767-1712. 2021, Volume 2. Published by Maimonides Fund. Copyright ©2021 by Maimonides Fund. No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of Maimonides Fund. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. WWW.SAPIRJOURNAL.ORG WWW.MAIMONIDESFUND.ORG CONTENTS 6 Publisher’s Note | Mark Charendoff 90 MICHAEL OREN Trial and Triage in Washington 8 BRET STEPHENS The Necessity of Jewish Power 98 MONA CHAREN Between Hostile and Crazy: Jews and the Two Parties Power in Jewish Text & History 106 MARK DUBOWITZ How to Use Antisemitism Against Antisemites 20 RUTH R. WISSE The Allure of Powerlessness Power in Culture & Philanthropy 34 RUTH CALDERON King David and the Messiness of Power 116 JEFF SWARTZ Philanthropy Is Not Enough 46 RABBI MEIR Y. SOLOVEICHIK The Power of the Mob in an Unforgiving Age 124 ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER Power and Ethics in Jewish Philanthropy 56 ANSHEL PFEFFER The Use and Abuse of Jewish Power 134 JONATHAN D. -

U.S. Role in the World: Background and Issues for Congress

U.S. Role in the World: Background and Issues for Congress Ronald O'Rourke Specialist in Naval Affairs Michael Moodie Assistant Director and Senior Specialist in Foreign Affairs, Defense and Trade Updated February 24, 2020 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44891 U.S. Role in the World: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The U.S. role in the world refers to the overall character, purpose, or direction of U.S. participation in international affairs and the country’s overall relationship to the rest of the world. The U.S. role in the world can be viewed as establishing the overall context or framework for U.S. policymakers for developing, implementing, and measuring the success of U.S. policies and actions on specific international issues, and for foreign countries or other observers for interpreting and understanding U.S. actions on the world stage. While descriptions of the U.S. role in the world since the end of World War II vary in their specifics, it can be described in general terms as consisting of four key elements: global leadership; defense and promotion of the liberal international order; defense and promotion of freedom, democracy, and human rights; and prevention of the emergence of regional hegemons in Eurasia. The issue for Congress is whether the U.S. role in the world is changing, and if so, what implications this might have for the United States and the world. A change in the U.S. role could have significant and even profound effects on U.S. security, freedom, and prosperity. It could significantly affect U.S. -

Erma Bombeck Bibliography of Adult Writings

Books by Erma Bombeck All I Know About Animal Behavior I Learned in Loehmann's Dressing Room. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1995. At Wit's End. Greenwich, Conn: Fawcett, 1967. Aunt Erma's Cope Book: How to Get from Monday to Friday- in 12 days. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979. The Best of Bombeck. New York: Galahad Books, 1991. (Contents: At wits end--Just Wait Till You Have Children of Your Own--I Lost Everything in the Post- natal Depression. ) Best of Erma Bombeck: Best-Loved Writing From America's Favorite Humorist. Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 1997. Erma Bombeck, Her Funniest Moments From “At Wit’s End”. Kansas City: MO. Hallmark Editions, 1977. Erma Bombeck: Giant Economy Size. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1980. Book Club edition. (Contents: At wit's end - Just wait till you have children of your own. - I lost everything in the post-natal depression). Family: the Ties That Bind-and Gag! New York: McGraw-Hill, 1987. Forever, Erma: Best-loved Writing from America's Favorite Humorist. Kansas City: Andrews and McMeel, 1996. Four of a kind: a Suburban Field Guide: a Treasury of Works by America's Best-loved Humorist. New York: Budget Book Service, 1996. [reprint of the following work] Four of a kind: a Treasury of Favorite Works by America's Best-loved Humorist. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985. The Grass is Always Greener Over the Septic Tank. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976. “How to Punctuate.” In How to Use the Power of the Printed Word : Thirteen Articles Packed With Facts and Practical Information, Designed to Help You Read Better, Write Better, Communicate Better. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881-1940 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6gn7b51j Author Myers, Eric Dennis Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881 - 1940 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Eric Dennis Myers 2013 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881 - 1940 by Eric Dennis Myers Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Joan Waugh, Chair The dissertation is a historical biography of Smedley Darlington Butler (1881-1940), a decorated soldier and critic of war profiteering during the 1930s. A two-time Congressional Medal of Honor winner and son of a powerful congressman, Butler was one of the most prominent military figures of his era. He witnessed firsthand the American expansionism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, participating in all of the major conflicts and most of the minor ones. Following his retirement in 1931, Butler became an outspoken critic of American intervention, arguing in speeches and writings against war profiteering and the injustices of expansionism. His critiques represented a wide swath of public opinion at the time – the majority of Americans supported anti-interventionist policies through 1939. Yet unlike other members of the movement, Butler based his theories not on abstract principles, but on experiences culled from decades of soldiering: the terrors and wasted resources of the battlefield, ! ""! ! the use of the American military to bolster corrupt foreign governments, and the influence of powerful, domestic moneyed interests. -

It's Official

ALUMNI TRAVEL WRITERS It’s Official \ CHARLES WHITAKER JEFFREY ZUCKER SCHOLARSHIPS IS DEAN OF MEDILL \ IMC IN SAN FRANCISCO SUMMER/FALL 2019 \ ISSUE 101 \ ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTENTS \ Congratulations to Max Bearak EDITORIAL STAFF DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI of the Washington Post RELATIONS AND ENGAGEMENT Belinda Lichty Clarke (MSJ94) MANAGING EDITOR Winner of the 2018 James Foley Katherine Dempsey (BSJ15, MSJ15) DESIGN Medill Medal for Courage in Journalism Amanda Good COVER PHOTOGRAPHER Colin Boyle (BSJ20) PHOTOGRAPHER Jenna Braunstein CONTRIBUTORS Erin Chan Ding (BSJ03) Kaitlyn Thompson (BSJ11, IMC17) Nikhila Natarajan (IMC19) Mary Neil Crosby (MSJ89) 11 MEDILL HALL OF 18 THINKING ACHIEVEMENT CLEARLY ABOUT 2019 INDUCTEES MARTECH Medill welcomes five inductees Course in San Francisco into its Hall of Achievement. helps students ask the right MarTech questions. 14 JEFFREY ZUCKER SCHOLARSHIPS 20 MEDILLIAN Two new funds aim to TRAVEL foster the next generation WRITERS of journalists. Alumni work in travel-focused positions that encourage others to explore the world. 16 MEDILL WOMEN The Nairobi Bureau Chief won for his reporting from sub-Saharan Africa. IN MARKETING PANEL 24 AN AMERICAN His stories from Congo, Niger and Zimbabwe chronicled a wide range of SUMMER Panel event with female extreme events that required intense bravery in dangerous situations PLEASE SEND STORY PITCHES alumni provides career advice. Faculty member Alex AND LETTERS TO: Kotlowitz sheds light on without being reckless or putting himself at the center of the story, new book. 1845 Sheridan Rd. said the judges, who were unanimous in their decision. Evanston, IL 60208 [email protected] 5 MEDILL NEWS / 26 CLASS NOTES / 30 OBITUARIES / 36 KEEP READING .. -

Ifflanrlffbtpr Ipralft

Directors to keep Coventry girls stunned Greenwood open /3 In Class L semlflnals/18 IfflanrlffBtpr Ipralft Wednesday, June 8, 1988 Manchester, Conn. — A City of Village Charm 30 Cents J Speed up is urged U to buy post office Bv Andrew J. Davis though the federal government eventual move. Monchester Herald has not made definite plans to "That very well might abandon the building. Plans to happen.’ ’ she said. Director Stephen Cassano will build a 34,000-square-foot post If MARC moves to the post ask the Board of Directors to office on Sheldon Road may be office, it will free up space at speed up the proposed purchase delayed for up to four years Bentley. The five classrooms of the Main Street post office to because of federal budget cuts. used by MARC could either be give officials more time in Work on purchasing the post used by the town Recreation planning a permanent home for office should begin immediately Department or possibly the Man the Manchester Workshop. because it will allow town offi chester Board of Education for Cassano wants the town to cials time to plan for a proposed special education programs, hr purchase the building, and con move to the building. Cas.sano said. vert it into a permanent home for said. Officials may be able to With the full reopening of the Manchester Association for negotiate a fixed price, and it will Highland Park School, the Re Retarded Citizens’ Manchester also allow MARC time to seek out creation Department is shifting Workshop, now housed at the federal grants for needed renova some of its programs to Bentley Bentley School building. -

How Sports Help to Elect Presidents, Run Campaigns and Promote Wars."

Abstract: Daniel Matamala In this thesis for his Master of Arts in Journalism from Columbia University, Chilean journalist Daniel Matamala explores the relationship between sports and politics, looking at what voters' favorite sports can tell us about their political leanings and how "POWER GAMES: How this can be and is used to great eect in election campaigns. He nds that -unlike soccer in Europe or Latin America which cuts across all social barriers- sports in the sports help to elect United States can be divided into "red" and "blue". During wartime or when a nation is under attack, sports can also be a powerful weapon Presidents, run campaigns for fuelling the patriotism that binds a nation together. And it can change the course of history. and promote wars." In a key part of his thesis, Matamala describes how a small investment in a struggling baseball team helped propel George W. Bush -then also with a struggling career- to the presidency of the United States. Politics and sports are, in other words, closely entwined, and often very powerfully so. Submitted in partial fulllment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 DANIEL MATAMALA "POWER GAMES: How sports help to elect Presidents, run campaigns and promote wars." Submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 Published by Columbia Global Centers | Latin America (Santiago) Santiago de Chile, August 2014 POWER GAMES: HOW SPORTS HELP TO ELECT PRESIDENTS, RUN CAMPAIGNS AND PROMOTE WARS INDEX INTRODUCTION. PLAYING POLITICS 3 CHAPTER 1. -

English Cafe

English as a Second Language Podcast www.eslpod.com ENGLISH CAFÉ – 123 TOPICS Charles Schultz and Peanuts, how to become a police officer, you and I versus you and me, yippee-ki-yay, to call dibs _____________ GLOSSARY comic strip – a series of drawings that tell a funny story, printed every day or every week in a newspaper or magazine * There was a funny comic strip about working in an office in today’s newspaper. Did you see it? to syndicate – to sell what one writes or draws to many newspapers; to sell one’s articles or comic strip to many newspapers * Dear Abby is an advice column that is syndicated to newspapers nationwide. high school yearbook – a book with many color photographs that is produced at the end of the academic year and shows what happened at a high school during that year, so that people can remember their high school experiences after they have graduated * Maxwell appears in his high school yearbook three times: on the soccer field, at the senior dance, and in chemistry lab. withdrawn – shy; timid; not interested in talking or spending time with other people; solitary; isolated * Carina is very withdrawn, always preferring to be alone with her books and music instead of spending time with friends. at its peak – at its maximum; at the highest point or amount of something * The price of oil is now at its peak; it has never been higher than it is right now. barber – a man who cuts other men’s hair * Quinton told the barber to be careful not to cut his hair too short. -

At School of the Arts Symposium

10 C olumbia U niversity RECORD May 21, 2003 Reporters Seymour Hersh and Matt Pacenza to Receive Columbia Journalism Awards highest award given annually by Press. Five years later, Hersh was career, Pacenza traveled to regularly appears in more than 100 BY CAROLINE LADHANI the faculty of the Journalism hired as a reporter for the New York Guatemala as a human rights newspapers nationwide, was a School. Times’Washington Bureau, where observer and educator. He also did finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Investigative reporter Seymour Of Matt Pacenza’s reporting, he served from 1972-75 and again public relations for a university 1985 and 1988. Her work has also Hersh and City Limits magazine which appears in the monthly print in 1979. theater and became a community appeared in numerous publications associate editor Matt Pacenza are publication City Limits and the His book The Price of Power: educator for an organ and tissue including Esquire, Atlantic, The receiving prizes for excellence in electronic City Limits Weekly, the Kissinger in the Nixon White bank. Pacenza earned a master’s Nation, Harper’s, Mother Jones journalism awarded by the faculty Journalism faculty said, “Pacen- House won him the National Book degree in journalism in 2000 from and TV Guide. She is the author of of Columbia’s Graduate School of za’s work stands out for its range Critics Circle Award and the Los New York University. four books, most recently Shrub: Journalism. and ambition. In the tradition of Angeles Times book prize in biog- Pacenza won 2002 National The Short But Happy Political Life Hersh will receive the 2003 Meyer Berger, his stories bring to raphy among other honors. -

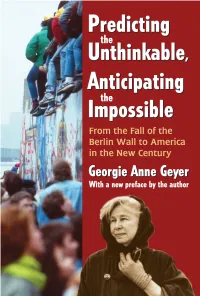

Predicting the Unthinkable, Anticipating the Impossible

First published 2011 by Transaction Publishers Published 2017 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © 2011 by Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2013009660 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Geyer, Georgie Anne, 1935- Predicting the unthinkable, anticipating the impossible : from the fall of the Berlin Wall to America in the new century / Georgie Anne Geyer, with a new preface by the author. pages cm “New material this edition copyright (c) 2013 by Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, New Jersey. Originally published in 2011 by Transaction Publishers.” ISBN 978-1-4128-5278-4 1. World politics--1989- 2. United States--Foreign relations--1989- I. Title. D860.G524 2013 909.82’9--dc23 2013009660 ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-5278-4 (pbk) ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-1487-4 (hbk) Contents Preface to the Paperback Edition by Georgie Anne Geyer xi Preface by Irving Louis Horowitz xvii Acknowledgments xxiii -

2015/16 Season Akeelah and the Bee Adapted for the Stage by Cheryl L

ERMA BOMBECK: AT WIT’S END 2015/16 SEASON AKEELAH AND THE BEE ADAPTED FOR THE STAGE BY CHERYL L. WEST BASED ON THE ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY BY DOUG ATCHISON DIRECTED BY CHARLES RANDOLPH-WRIGHT ERMA BOMBECK: AT WIT’S END TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Artistically Speaking 5 From the Executive Producer 7 Dramaturg’s Notebook 9 Title Page 11 Time and Place, Cast List, For this Production 12 Who’s Who - Cast ARENA STAGE 1101 Sixth Street SW 12 Who’s Who - Creative Team Washington, DC 20024-2461 ADMINISTRATION 202-554-9066 SALES OFFICE 202-488-3300 15 Arena Stage Leadership TTY 202-484-0247 www.arenastage.org 17 Board of Trustees © 2015 Arena Stage. All editorial and advertising material is fully protected and 17 Thank You – Next Stage Campaign must not be reproduced in any manner without written permission. 18 Thank You – The Annual Fund Erma Bombeck: At Wit’s End Program Book 21 Thank You – Institutional Donors Published October 9, 2015. Cover Photo Illustration by 22 Theater Staff Ed Fotheringham Program Book Staff Anna Russell, Associate Director of Marketing and Publications David Sunshine, Graphic Designer 2015/16 SEASON 3 ARTISTICALLY SPEAKING We are pleased to welcome back Allison Engel and Margaret Engel to Arena Stage with their director David Esbjornson. These dynamic twin sisters wrote Red Hot Patriot: The Kick-Ass Wit of Molly Ivins, their one-woman show which brought back the late political humorist Molly Ivins, with Kathleen Turner, and rocked the Cradle three years ago. Erma was a journalist, mother and housewife who wrote over 9,000 newspaper columns and 12 books in her lifetime, describing ordinary, suburban life with insightful comments like: “Motherhood is the second oldest profession, but unlike the first, there’s no money in it.” Through her commentary on motherhood, a woman’s place in the workforce, marriage, child rearing and political equality, Erma Bombeck reached 30 million people three times a week.